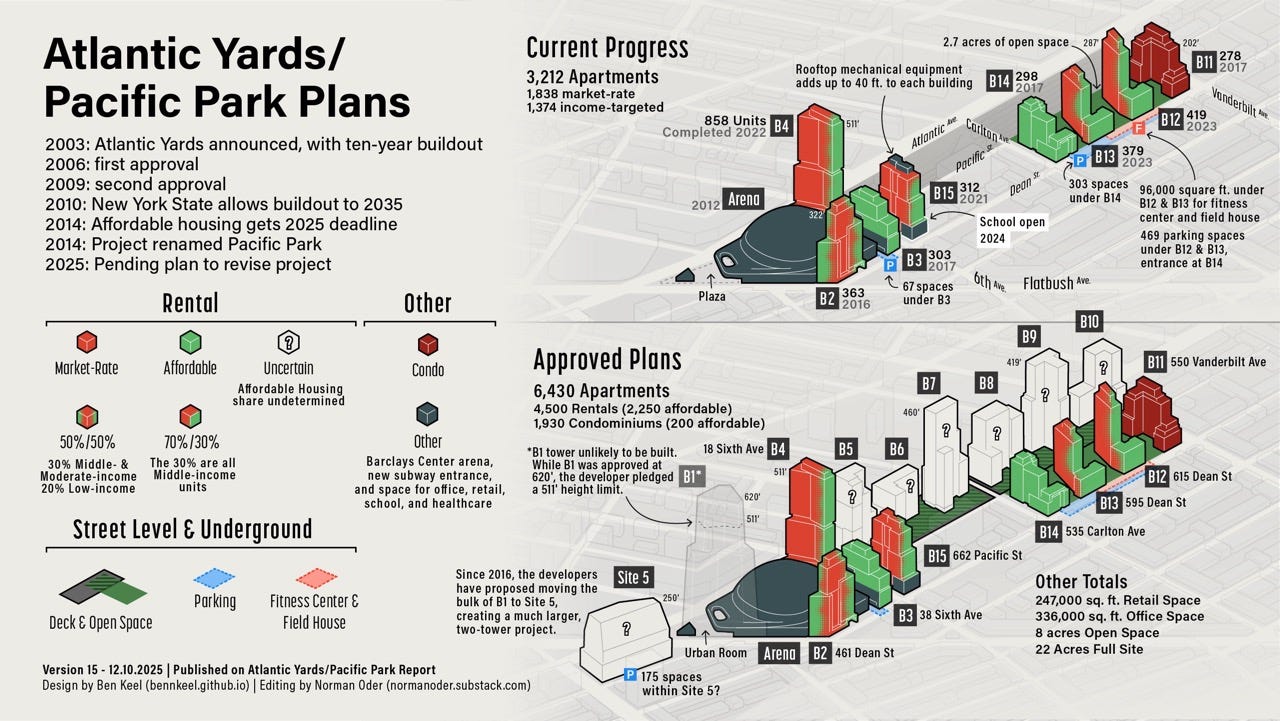

Workshop Yields a Few Clues on Project’s Future, But Big Questions Still Loom

Developers might re-start construction in two years. They (vaguely) promise lower-income housing. How much depends on “public resources.” Accountability? Stay tuned.

In this long article, the most important info is in the top sections. Subheadings should help those who skim.

The third in a series of carefully managed workshops on the future of Atlantic Yards, held online Jan. 22, yielded some incremental clues about the project’s timing and affordability, while dancing around difficult questions like subsidies sought and a new accountability structure.

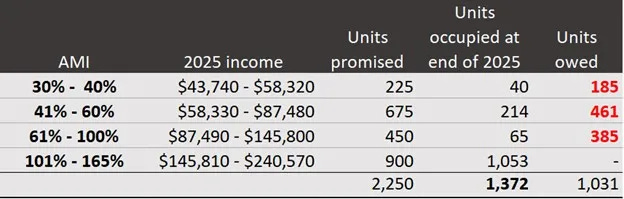

The latter remains a glaring issue, given the project’s failure to deliver 876 (of 2,250) promised affordable housing units by a May 2025 deadline, and the willingness of Empire State Development (ESD), the state authority that oversees and shepherds the project, to compromise on enforcing penalties.

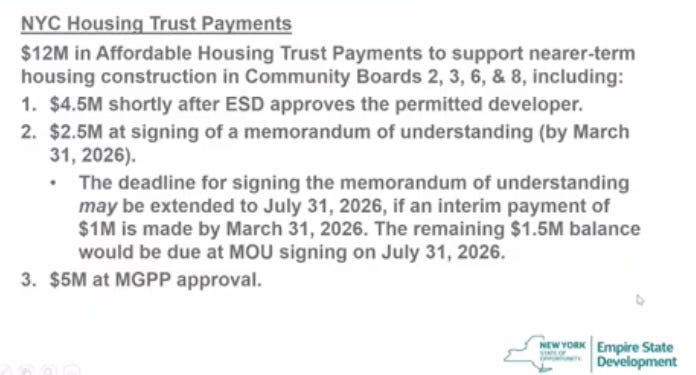

ESD negotiated $12 million in payments rather than steadily accruing $1.75 million a month and said, for the first time, that full enforcement would add to project costs, essentially waving away what a state official once called “nonnegotiable.”

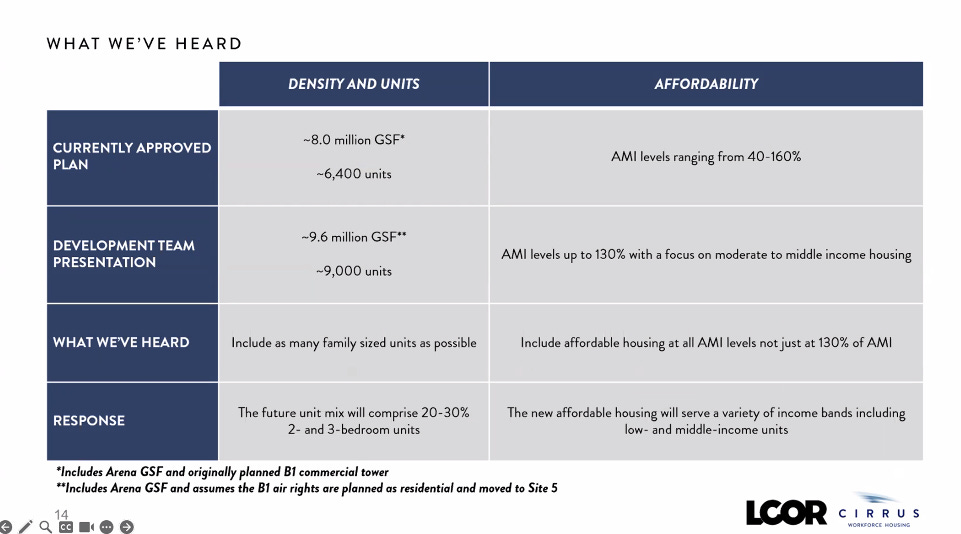

No new images of the proposed project were presented, but developers Cirrus Workforce Housing and LCOR acknowledged a need to build more deeply affordable housing. That was a change in rhetoric, if not a specific pledge.

They also promised 20% to 30% two and three-bedroom apartments, which, unmentioned, would be less than the original promise but consistent with the record so far. So that pledge may not be burdensome.

Given constraints posed by a complex site and other costs, like tariffs, they suggested that more “public resources”—subsidies, tax breaks, financing—were needed to fund not just the housing but also the platform needed for construction over the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s (MTA) two-block Vanderbilt Yard, used to store and service Long Island Rail Road trains.

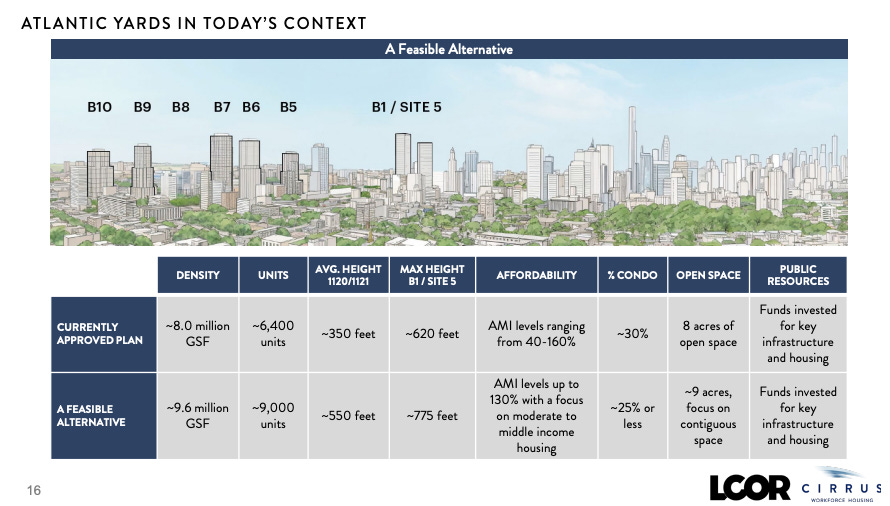

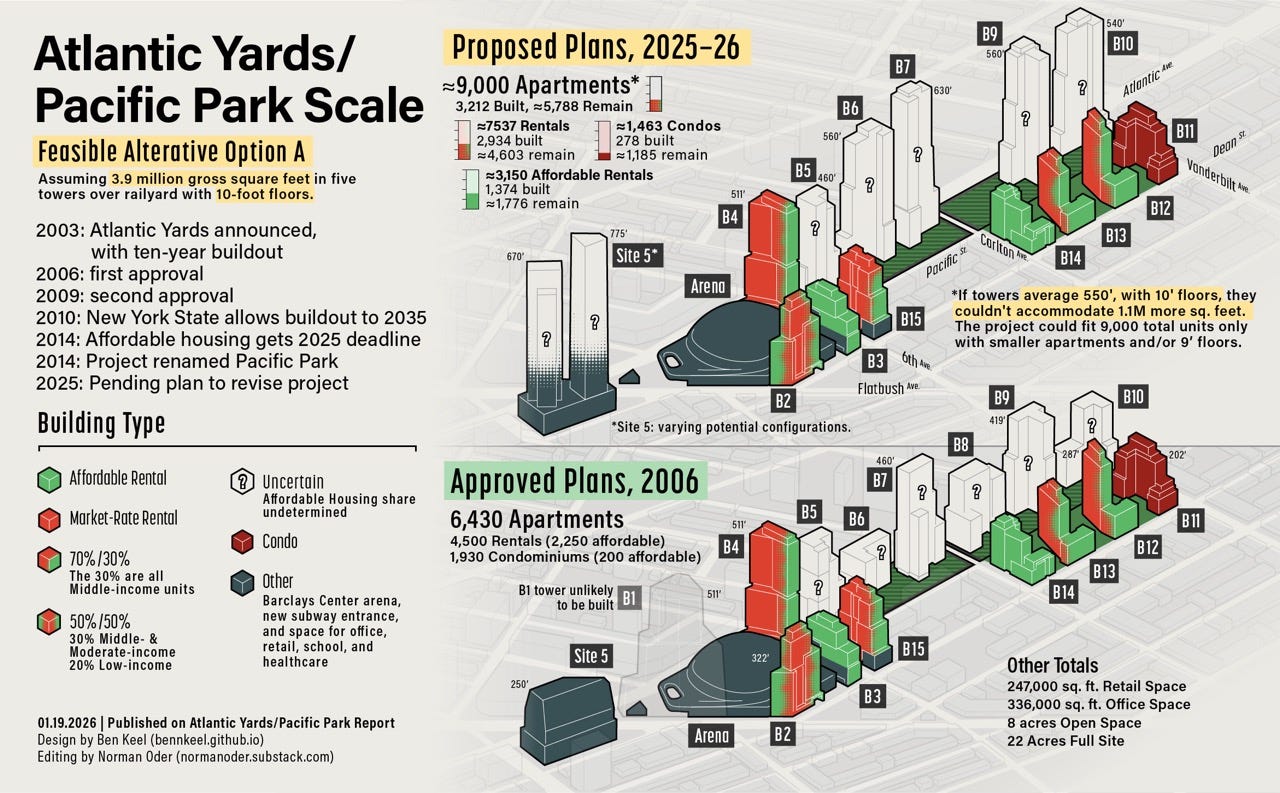

Unmentioned: the developers’ requested 1.6 million more square feet of bulk—allowing the project to grow to 9,000 apartments, from an approved 6,430—would be an indirect subsidy, worth perhaps $320 million. The MTA originally bid out the air rights, which are still being paid off.

That square footage would allow for more than 100 additional floors spread over five towers.

My take: an unbiased analyst should assess the value and cost of the public resources requested, and measure them against alternative uses. (That could be part of a larger analysis of the project’s financial viability, as the coalition BrooklynSpeaks, which advocates for an improved plan, has suggested.)

What’s the timing?

An ESD representative said that construction might re-start as early as late 2027 or the first half of 2028, given required public hearings and an environmental review. (That implies a 1.5-year public process, not a 2-year one, as has been discussed.)

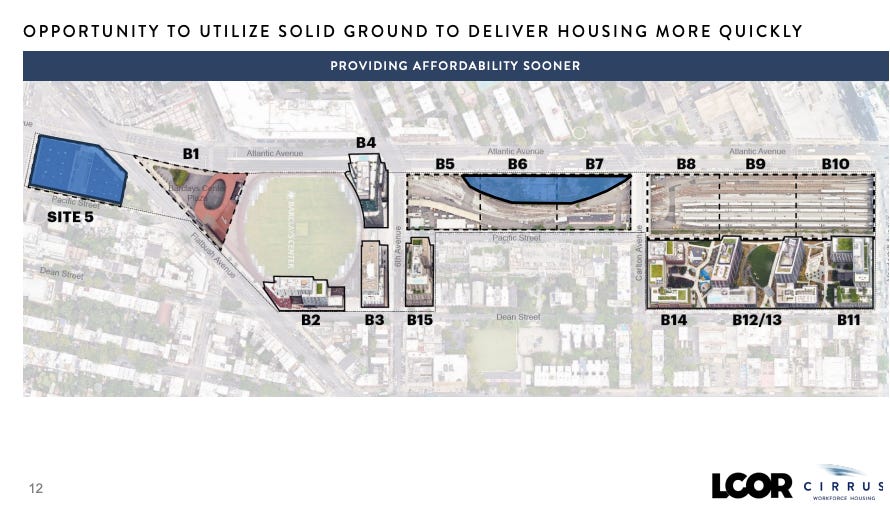

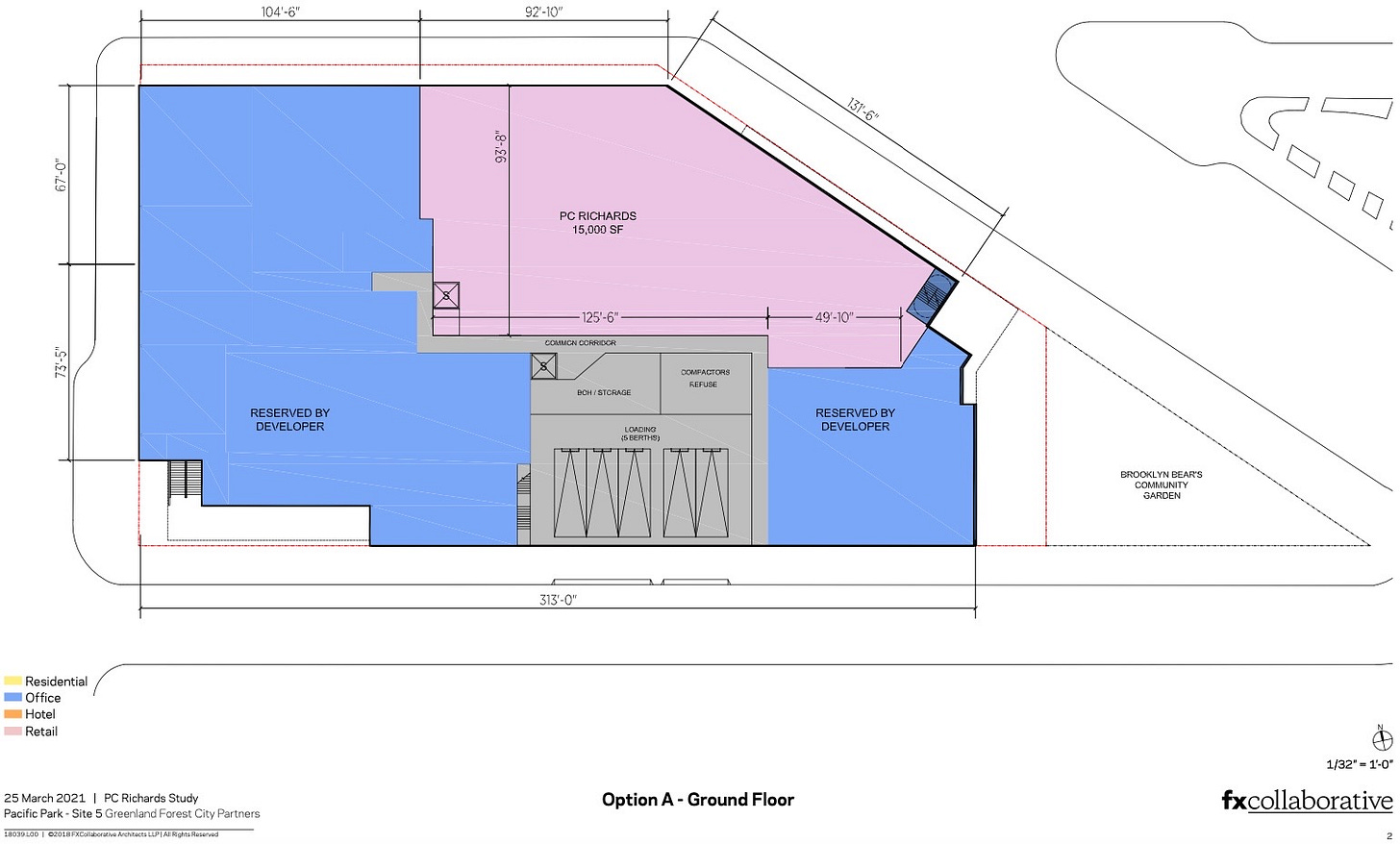

The target parcels would be at two terra firma sites that jut below Atlantic Avenue, known as B6 and B7, as well as Site 5, the parcel catercorner to the arena, long home to the big-box stores P.C. Richard and the now-closed Modell’s, now home to the temporary Brooklyn Basketball Train Center.

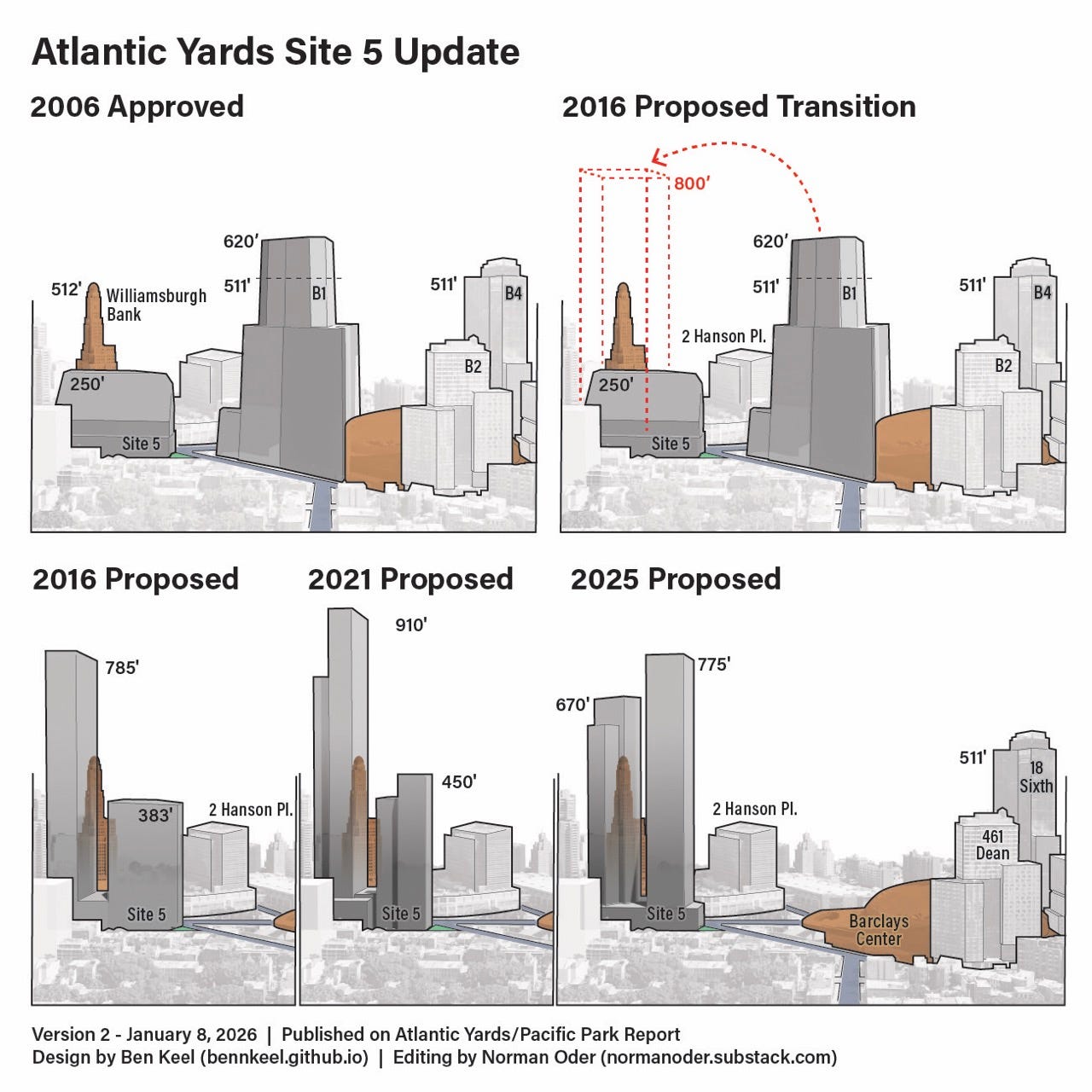

Site 5, though approved in 2006 and in 2009 for a substantial building, is expected to host a far larger two-tower project if the state approves a bulk transfer from the unbuilt B1 tower, once slated to loom over the arena.

The developers also acknowledged tension between wanting to get platform construction done quickly and the impacts of concentrated construction. (Indeed, there are now more neighbors.)

Workshop overview

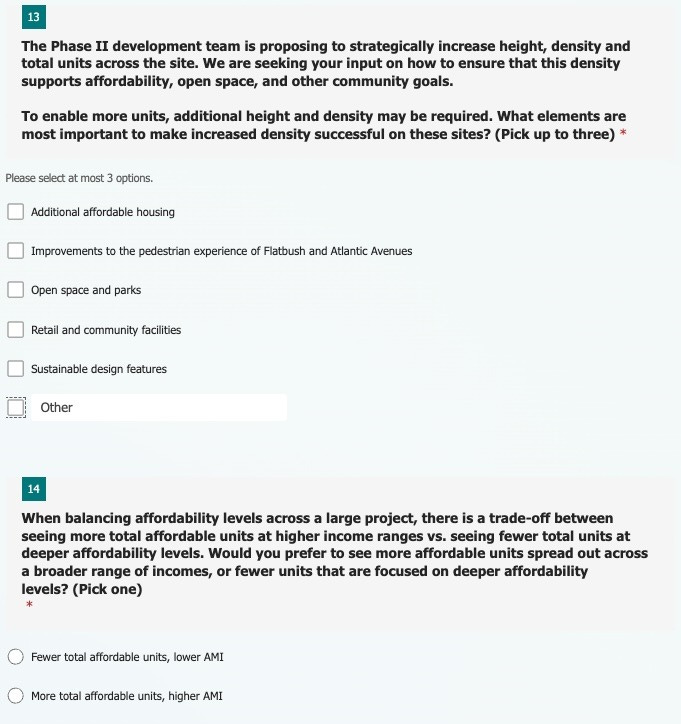

More than 40 questions were presented at the online workshop. (I’ll add a link to the video when available. The presentation will be here.) More than 130 people attended, though nearly 20 represented the developers, lobbyists, ESD, and its consultants.

While the developers came off as both pragmatic and agreeable, they were also strategic, shutting down a few challenging questions—about scale, about their partners—without full candor.

Given the format of the workshop—no chat, no public discussion, no opportunity for attendees to endorse others’ follow-up questions—it’s difficult to assess public reaction.

That said, a plurality of questions concerned affordability, while others were concerned about getting the project built, the project’s impacts, and accountability.

BrooklynSpeaks, for example, had encouraged people to ask about collecting damages, supplying deeply affordable housing, the manager of open space, the provision of indoor public gathering pace, public input on approving changes, and new accountability measures.1

Tensions over scale

The developers continued to present the requested 1.6 million additional square feet as a 20% increase, relative to the total project, rather than framing it as a more dramatic—and informative—46% on the railyard sites.

Asked about projects of comparable scale, the developers side-stepped the issue, citing various rezonings in the city that allow larger buildings per parcel. (That’s not the same, as I explain below.)

By contrast, a few attendees asked why the scale couldn’t be increased, given the need to build more housing, They were told it was limited by infrastructure—the foundations for the platform—and the increasing costs.

The five towers built over the railyard, said Joseph McDonnell, managing partner of developer Cirrus Workforce Housing, would average about 550 feet. The total floors, including at Site 5, “would vary approximately between 40 and 80 floors.”

(The taller of two towers at Site 5 would be 775 feet, so it’s unlikely it would get to 80 floors.)

Their dimensions suggest standard 10-foot floors, which raises questions about how they could fit the project in the floor plates they’ve apparently chosen, as I wrote, with my collaborator Ben Keel.

The key: subsidies

One submitted question was a fat pitch: will the developers and state work with community partners to ask the state and the city for infrastructure funds?

“Approaching the various sort of governmental agencies which are required to move a project like Atlantic Yards together is something we’re very interested in doing,” responded LCOR Principal Anthony Tortora. (Well, they’ve already been lobbying.)

Joel Kolkmann, ESD’s Senior VP, Real Estate and Planning added, “We’ll need all the support we can get in securing funding... When we have a sense of what’s needed, we certainly will want to work with our partners at the state, both in the governor’s office, of course, but at the state legislature to secure funding.”

Well, ESD is an arm of the governor, and presumably can supply subsidies or tax breaks. It would be interesting to learn what they seek from the legislature. Cirrus has Bolton-St. Johns, one of the state’s top lobbying firms.

As I’ve written, the stalled Manhattan megaproject Hudson Yards, which also requires a platform, was rescued by a little-scrutinized plan to direct payments in lieu of taxes to fund infrastructure. Some have called it a $2 billion bailout.

Nuggets of news: parking and open space

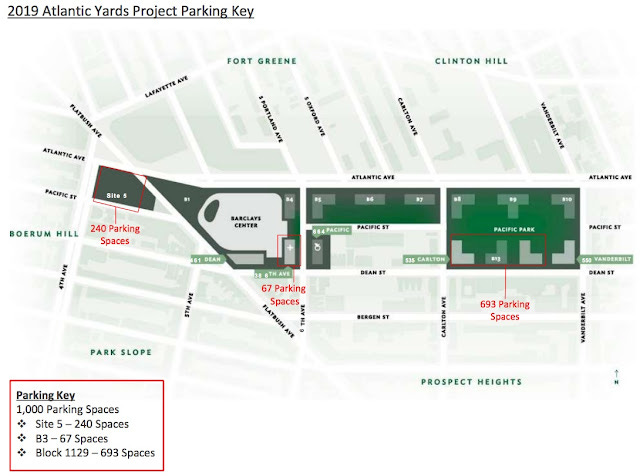

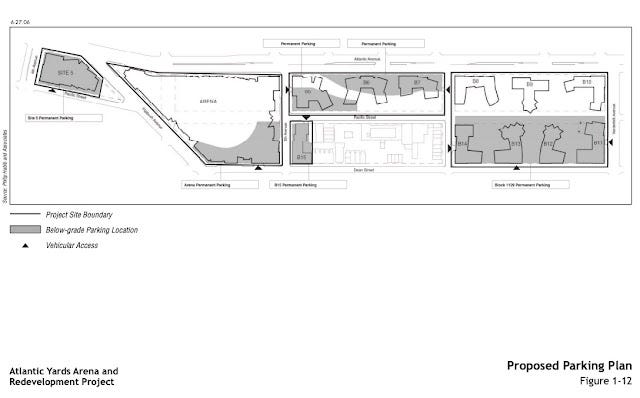

The developers do plan to add some parking, which has been steadily subtracted from the project, though they didn’t specify location or scope.

Also, they’ve hired the firm Town Square, which has worked for various public and private clients, to manage the project’s nearly 3-acre open space, aka Pacific Park.

Still, ESD does not seem ready to revisit the Pacific Park Conservancy, the nonprofit that oversees that open space, which is essentially opaque, with no website nor public meetings.

A new phone number and email will be provided to reach both Town Square and the developers.

Presentation: ESD

The workshop began with a presentation from the hosts. (The screenshots and slides in this article come not only from the Jan. 22 presentation but also the two previous ones.)

ESD’s Kolkmann said nearly 300 people had participated in the two previous workshops, and more than 400 had completed an online survey, which closed Jan. 23.

(Note how the Plumbers Union urged its members to respond, to “show support for union jobs and real housing for working families.” Any organized campaign could skew survey responses.)

Kolkmann repeated a part-sheepish acknowledgement that, despite the project’s “significant” progress, challenges have led to public frustrations, but ESD officials were “very excited” to have a new development team.

Presentation: developers’ overview

McDonnell said they aimed “to build housing across the income spectrum,” which of course is a general goal.

Cirrus Workforce Housing is backed by the pension funds of various (mostly construction) city labor unions. It’s also an affiliate of Cirrus Real Estate Partners, which pursues “investments that offer asymmetric risk-return profiles and significant downside protection.”

Tortora said LCOR has delivered over 30,000 apartments and over 6 million square feet of development in the greater New York area, and has extensive experience with public-private partnerships involving complex infrastructure sites.

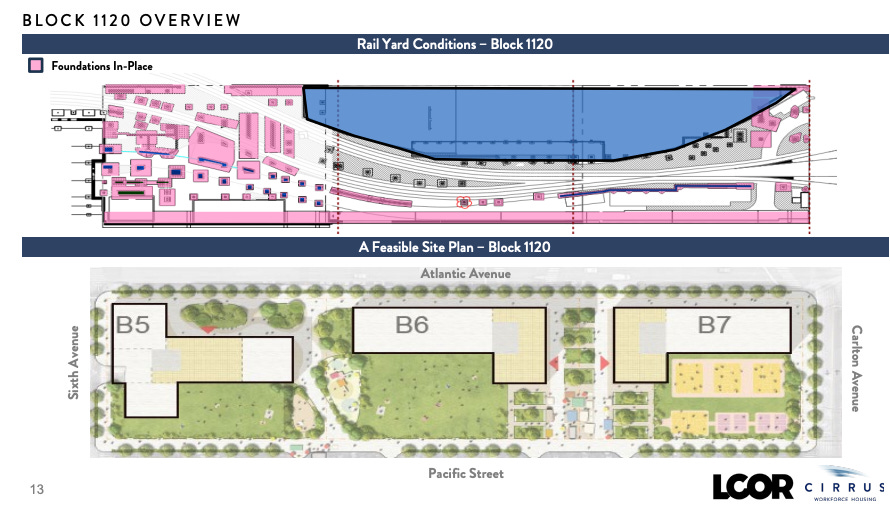

To reduce the cost of building over the two-block railyard, they propose first focus on the solid ground occupied by Site 5, B6, and B7. “By increasing the density of these sites and constructing buildings and the platform simultaneously, we will be able to deliver more housing sooner.”

Note: it’s unclear how much of the platform adjacent to B6 and B7 is needed to make construction viable. (I asked, but didn’t get an answer.) Or would there just be a big fence around the rear?

Cirrus/LCOR, taking a cue from predecessor Greenland USA, has proposed thinner, taller buildings, making it easier to build on terra firma.

I presume that “shifting more density” to Site 5 simply reiterates the plan, as ESD endorsed in 2021 in response to a proposal from Greenland, which had taken over from original developer Forest City Ratner after a rocky joint venture, to move the bulk from to Site 5.

Their value proposition

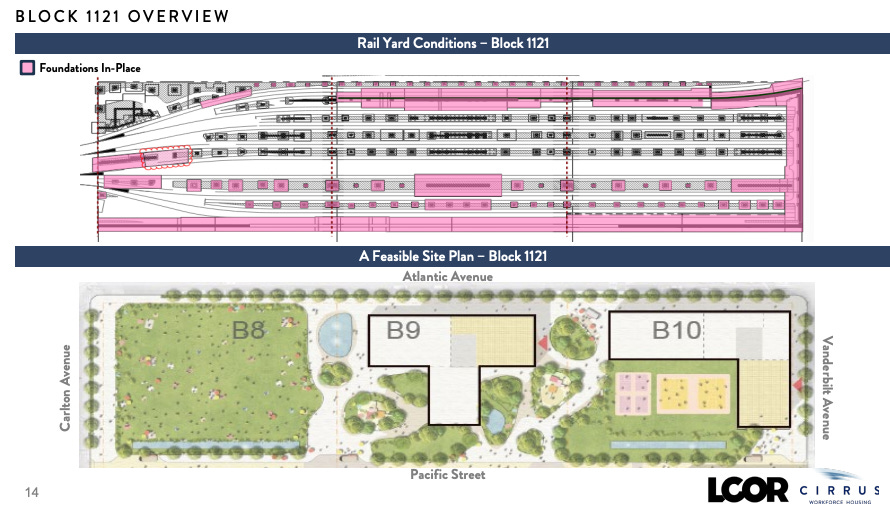

Tortora reiterated that previous investments by Greenland to build foundations for the platform gives the development team a head start, both in cost and timing.

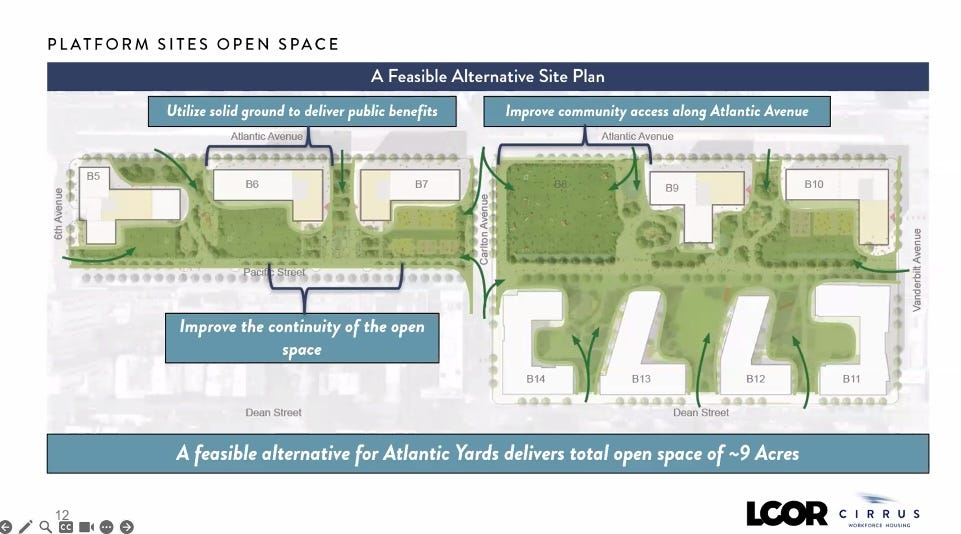

The building redesign for narrower footprints, he said, would increase the amount of open space on the platform blocks and improve its connectivity.

Unmentioned: an increased population, as my article below suggests, would outpace the increase in open space.

By eliminating the proposed B8 tower, at a site complex and costly to build on, they could deliver another acre “as a public park amenity,” Tortora said. “Given its location at the center of the platform blocks, we believe this could be a transformative amenity.”

He offered no timing, however. Presumably the second block of the platform, east of Carlton Avenue, would built in the last phase of the project.

McDonnell said Atlantic Yards could deliver significant community benefits, including open space and “indoor and outdoor community-designated spaces, including an intergenerational center.”

(That intergenerational center—offering child care, and youth and senior services—has long been a project requirement.)

He also promised layouts conducive to small, pedestrian-driven local retail.

Presentation: density

McDonnell said the proposed density increase would not only make the project viable, but also would focus on “rental housing across the income spectrum,” not office space or condos.

Well, the original idea was to concentrate office space around the arena, near transit. While Cirrus and LCOR may envision fewer condos than previous developers, they still plan a significant increase; I estimated 1,185 more, on top of the 278 built.

The project, McDonnell said, is “designed to keep total height below 800 feet, in contrast to some other buildings that were recently built on Flatbush Avenue.”

Well, one building is taller, the “supertall” Brooklyn Tower, which relies on a transfer of air rights from an adjacent landmark bank. (The recently proposed 395 Flatbush Avenue Extension would rise 840 feet.)

Presentation: affordability

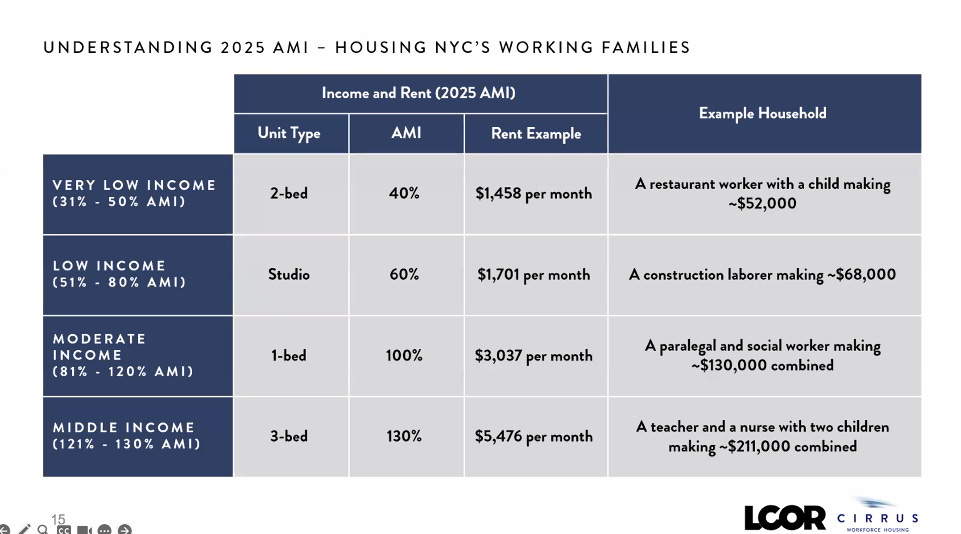

“We want to clarify,” McDonnell said, that “our original presentation, with respect to a feasible proposal, was suggesting capping AMIs”—Area Median Income levels, which set “bands” for income-targeted “affordable housing”—at 130%, while providing affordable housing across the income spectrum, including low incomes.”

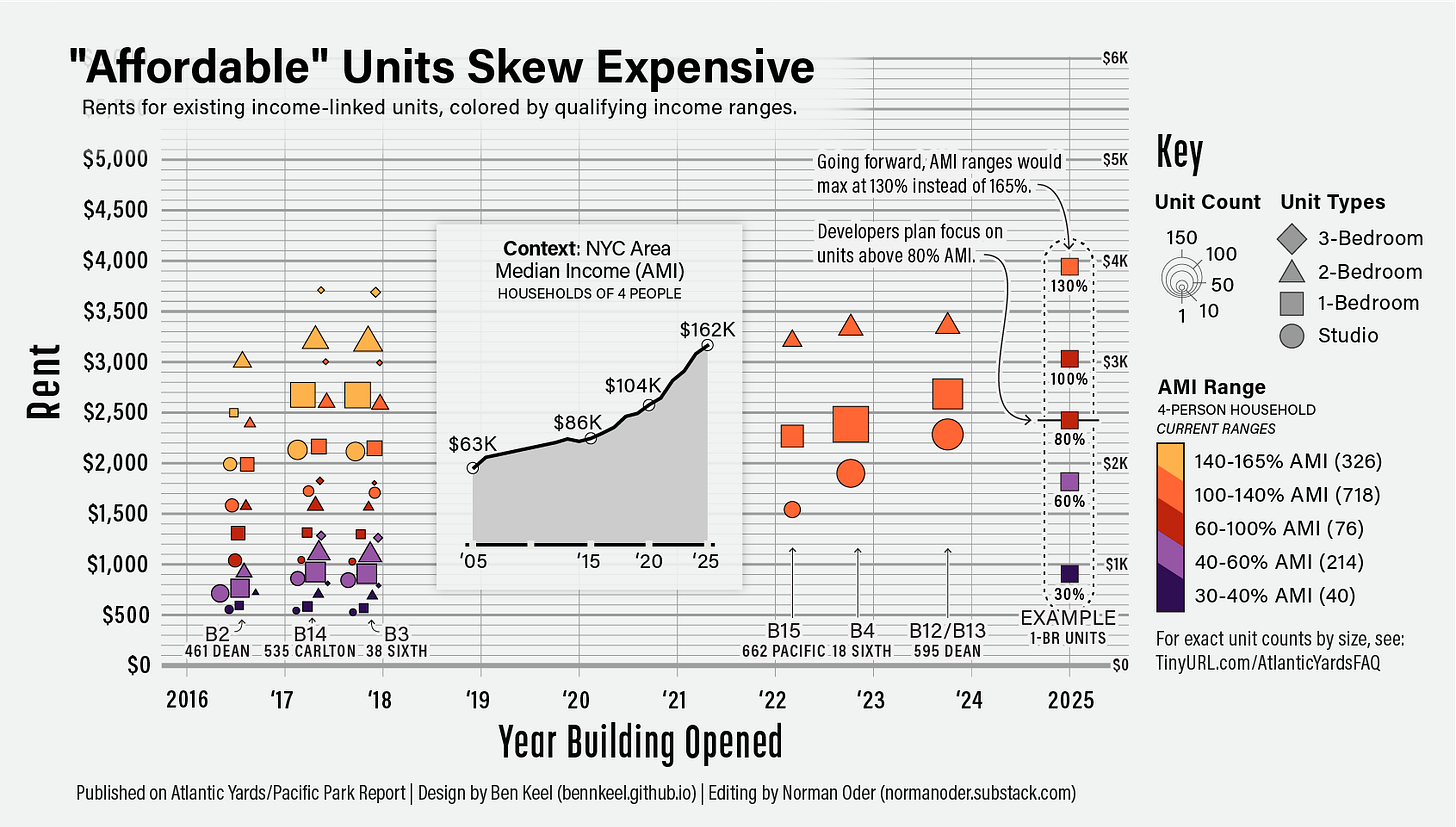

Indeed, it left room for low-income housing. But the claimed “focus on moderate- to middle-income housing”—above 80% of AMI—prompted pushback from workshop attendees Nov. 18, as noted in the article linked below, and criticism at a Dec. 2 meeting of the advisory Atlantic Yards Community Development Corporation.

On Jan. 22, McDonnell’s statement represented a rhetorical shift, though not a repudiation of their claimed focus.

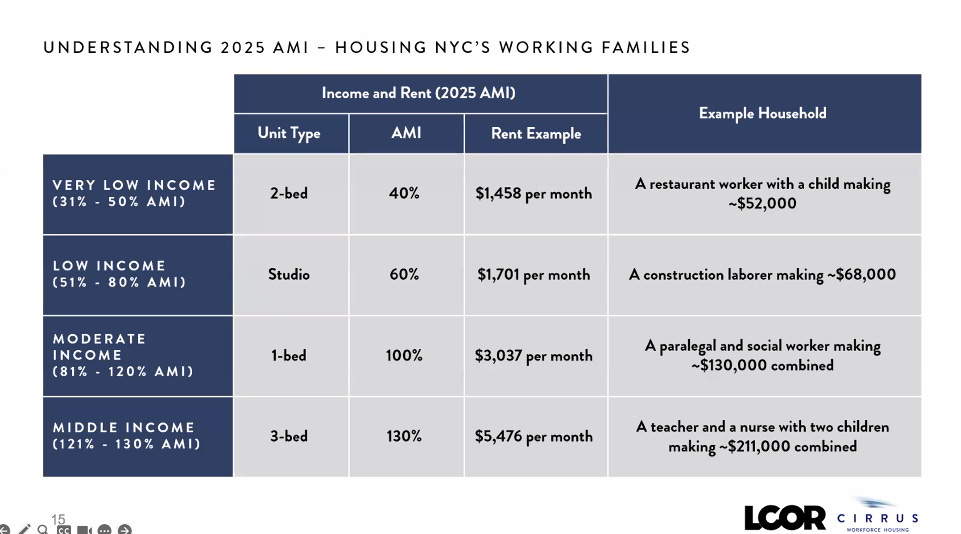

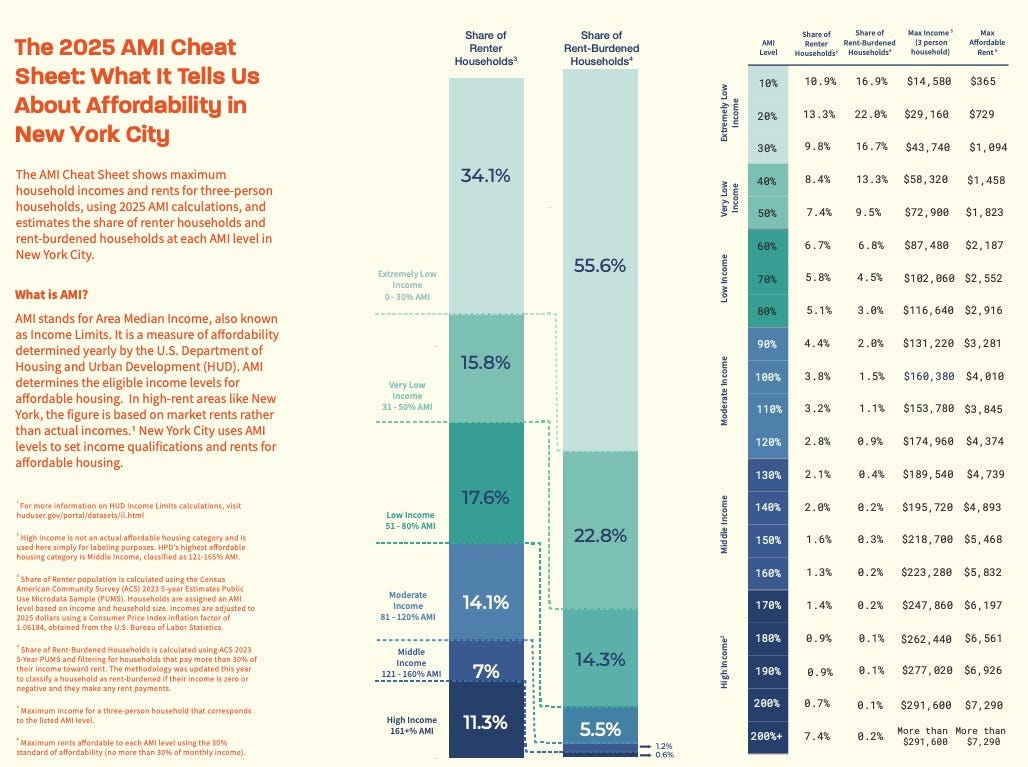

He added that they’d heard feedback about the need to talk about AMI, the base for calculating affordability, in more practical terms, so they produced the slide below.

Note that the two less costly examples were at 40% and 60% of AMI; they didn’t include 80% of AMI.

Note that those rents are based on a 2025 baseline, so when buildings open—perhaps in 2030 at the earliest—the rents would be higher, perhaps significantly. Also note that a three-bedroom market-rate apartment at 18 Sixth Ave., (B4, Brooklyn Crossing) rented for $6,200 two years ago.

New variables

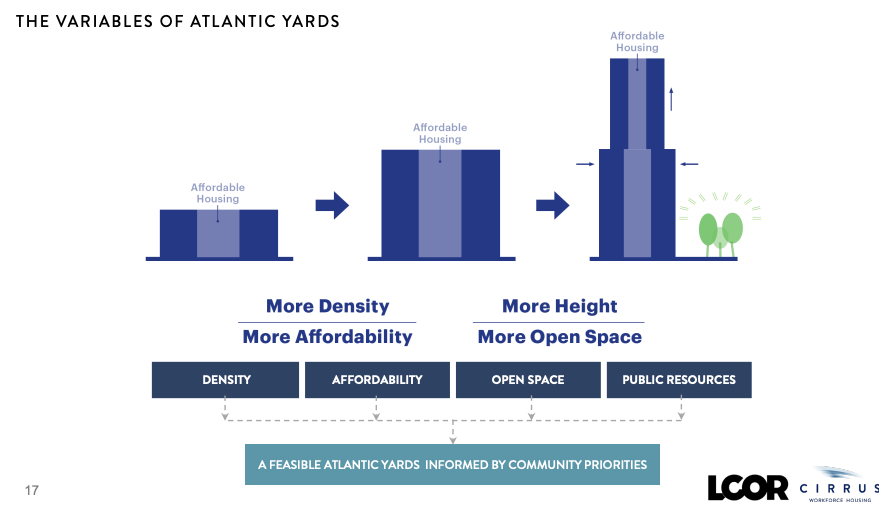

At the first workshop, on Nov. 18, a simplistic slide from the developers suggested that more density would deliver more affordability, while taller, thinner buildings, would mean more open space.

I suggested that a key was “public resources”—the subsidies and tax breaks requested—as well as the developers’ cost basis and profit expectation, neither of which have been disclosed.

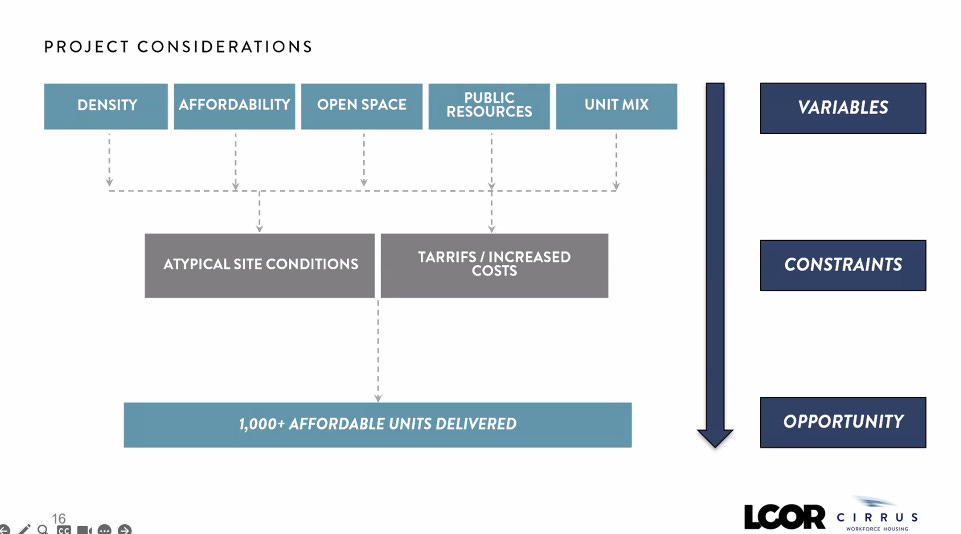

On Jan. 22, McDonnell said they “continue to modulate the variables.” As the graphic below suggests, they added “unit mix”—the size of the apartments—to the variables.

They added constraints: atypical site conditions, given construction over the railyard below, plus tariffs and increased costs, which other projects face.

Again, looming is the unspecified request for “public resources.”

How many affordable units total?

“One thing we’ve consistently heard is a need to deliver it with pace in a reliable way,” McDonnell said, “to ultimately provide 1,000-plus affordable units [at levels] across the income spectrum.”

Indeed, delays mean ever more expensive “affordable” units, given rising AMI.

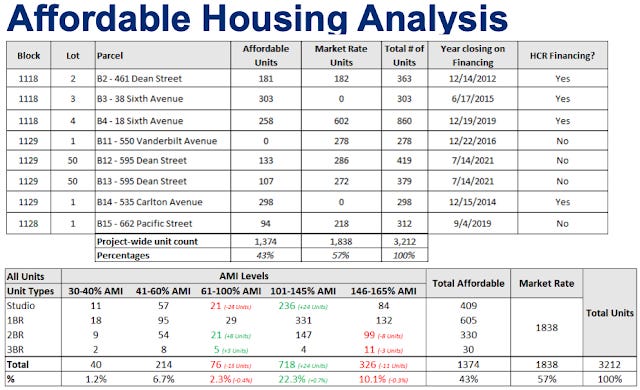

Perhaps McDonnell was being cautious, but an increase of 1,000 affordable units, given the 1,374 below-market units built, would be modest. To stay consistent with the approved plan—35% affordable units (2,250 of 6,430), in terms of unit count—they’d have to build some 3,150 affordable units, or 1,776 more.

Caveat: maybe they don’t intend to build the stated 9,000 total apartments, as developers typically request more than they need. (They didn’t mention affordable for-sale condos, another lingering promise.)

What’s next

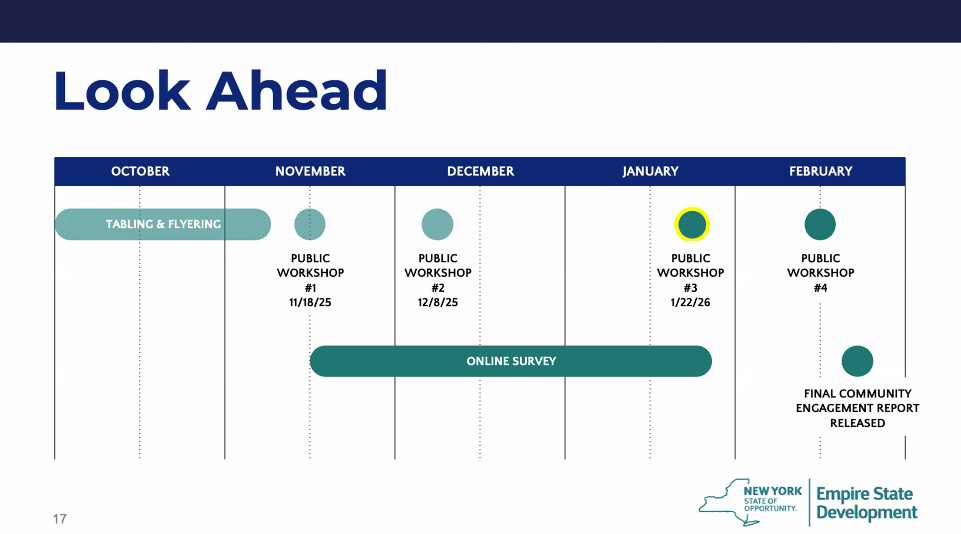

Kolkmann said a fourth workshop would be held virtually in February, with no date yet set. At that workshop, they’ll “present the first draft of the community engagement report and update you all on early thinking on a proposed project plan.”

Feedback from that report will inform a final report, which would apparently be issued shortly afterward. (Given the tenor of questions, and the amount of disclosure, public input likely could shape the plan only at the margins.)

That would allow for the developers and ESD to reach a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) by the end of March—or, perhaps, by the end of July.

Following that MOU, a round of formal public hearings, part of a required environmental review, would take place before a new project plan is approved.

Getting more people involved

Assemblymember Jo Anne Simon, a key supporter of BrooklynSpeaks, encouraged more in-person engagement, and suggested that, in contrast with previous in-person sessions, they include a report-back function so attendees can learn from others’ discussions.

Simon encouraged consultation regarding the project’s Design Guidelines, which need an update, and said the city Parks Department had experience with participatory design.

Also attending were two Simon aides, state Sen. Jabari Brisport, and an aide to Assemblymember Bobby Carroll. (I might have missed some other officials or staff.)

Questions & Answers overview

Annie White of consultant Karp Strategies managed the Q&A session, alternating written questions with speakers. Rather than proceed chronologically, I’ll group them. They include:

Accountability: justifying $12M

Flashback: the negotiation

Accountability: a more explicit equation

Accountability: what next?

Increasing density?

Unusual density?

Challenges in building fast

Affordable housing: rent levels

Affordable housing: who’s rent-burdened?

Affordable housing: lottery preference

Affordability enforcement

Affordability: a Mamdani effect?

Affordability: displacement and lower incomes

Affordability: consistent distribution of larger units?

Impacts of growth: school, shadows, wind

Impacts of growth: garden, Atlantic Avenue, loading docks

Impacts of growth: parking

The phantom minor partners

Open space and community amenities

The Pacific Park Conservancy and open space

Could arena operator be forced to pay?

MWBE questions

Climate change and geothermal

The names of those submitting written questions were not identified. Those speaking were identified, so I’ll name some of them.

Accountability: justifying $12M

How would “prior failure to perform penalties be addressed,” asked Ethel Tyus, former Land Use Chair for Brooklyn Community Board 8 and a member of the Atlantic Yards Community Development Corporation.

“I believe you’re referring to the liquidated damages for the affordable housing shortfall,” Kolkmann said, shifting discussion from any forward-looking structure.

“We have worked with the development team to secure $12 million towards that liquidated damages number,” Kolkmann said, noting the money would go to a city trust fund for affordable housing projects located near the Atlantic Yards site.

That limited payment provoked criticism from both BrooklynSpeaks and an array of local elected officials, led by Council Member Crystal Hudson.

“So that, to us, is part of a win here. We also want to be mindful that there are a lot of costs with this project, a lot of challenges,” Kolkmann continued said. “We want to keep this project moving and doing our best to minimize costs that are added to the project.”

That waves away the responsibility of former developer Greenland USA, which remains a part of the project, albeit as a minority partner, and could ultimately profit.

Flashback: the negotiation

At the Oct. 9, 2025 meeting of the Atlantic Yards Community Development Corporation, Director Gib Veconi, noting that the damages could be far larger, asked how was that $12 million figure was set.

Anna Pycior, ESD’s Senior VP, Community Relations, called it “a combination of both actual money now,” which they didn’t necessarily think they could’ve gotten by pursuing damages, “alongside actual progress” with a new developer.

Was it, asked Veconi, “a sort of arbitrary balance”?

“It was the result of negotiation,” Kolkmann said.

It also protects Cirrus, which Veconi two months earlier described as “speculating in the distressed debt” of Greenland, “taking on something that has risk and liability in the form of these liquidated damages."

Cirrus entered the project by buying most of Greenland’s debt, presumably at a deep discount, gaining the benefit of the developer’s embedded investment in a new railyard and platform foundations, precursor to vertical development.

I edited the developer’s slide, above, to point out that a key unmentioned variable is their investment cost and expected returns.

Accountability: a more explicit equation

Why, asked Elliot Hoffman at the Jan. 22 session, did ESD not pursue full penalties?

“Collecting those fees would ultimately come out of the developers’ project budget,” said Kolkmann, implicitly dismissing the notion that the new development team assumed the risk of such damages.

“So it [would] really complicate that from a cost perspective, and require more subsidy,” he continued. “And, you know, I hear you, $12 million is not a lot… But it was, you know, something that ESD demanded, that there be a meaningful payment that goes to that fund.”

Was the cost of pursuing the damages, Hoffman followed up, higher than the potential gain?

Not necessarily, responded Kolkmann, citing the risk of delays caused by litigation. That shouldn’t be ignored, but ESD had and has leverage, I’d contend, regarding the approval of new density on Site 5.

The only time the government has the upper hand is before the contract is signed. However, other factors, such as Gov. Kathy Hochul’s presumed desire to celebrate progress as she runs for re-election, also intervene.

Accountability: what next?

Asked how ESD plans to improve accountability and transparency, Kolkmann said, vaguely, that project documents “can outline ideas and mechanisms for creating accountability and transparency.”

“That’s something that we want to continue to discussing with folks,” he said. (BrooklynSpeaks, for example, in 2022 proposed a new governance structure.)

The issue, however, isn’t just the documents, it’s the willingness to pursue enforcement.

Increasing density?

Natalie Leonard, who described herself as rent-burdened with four roommates, asked a question in sync with, if not directly influenced by, YIMBY groups like Open New York.

“If you were building as many units as was possible within the laws of physics, how many could you get?” she asked. “And why are we not pushing for that many?”

ESD’s Kolkmann had the semi-awkward role of having to push back. He said trade-offs need to be studied, such as “air quality and noise and traffic and shadows and open space impacts.”

(Indeed, a 40% increase in population would outpace an 18.75% increase in open space, I estimated, making an already unfavorable ratio even worse.)

“We think this is a really good balance,” he said. Surely the ESD’s consultants will agree with that in the environmental review.

Later, Sean Hart asked about “radically more housing units.”

Developer McDonnell cited the already installed foundations for the platform. “We’re confident that those foundations can support buildings of the heights”—and, implied, bulk—“that we propose, the roughly 550-foot average.”

To build taller, he said, they’d have to undo some of the previous work, which would be costly and time-consuming.

“Beyond that, and I think sometimes people can can under-appreciate this,” McDonnell said, “the taller you build buildings, expenses actually tend to increase almost exponentially.” A taller building requires “more concrete, more steel, more time, more cranes.”

(Architect John Massengale, in a comment on my article earlier this week, made similar observations.)

Increased height can lead to wind-related delays, added McDonnell.

“We have to acknowledge that as buildings get taller and density or bulk increases in a tight area like Brooklyn like this,” he said, “there would be further environmental impacts” citing “things like the schools. So there’s actually a natural limit to these sites.”

Unusual density?

White read some written questions, including mine: “What other large real estate projects in New York City have a density comparable to what’s being proposed here, which is about 409 apartments per acre?”

LCOR’s Tortora, clearly prepared, responded that they wanted to “ensure our proposed plan is contextual to the surrounding area. And as we could all acknowledge, the backdrop of this area of Brooklyn has changed dramatically since this project was conceived in the early 2000s.”

“Our proposed density,” he said, “is consistent with the Atlantic Avenue portion of AAMUP,” the Atlantic Avenue Mixed-Use Plan, a recent rezoning.

“It’s less than Downtown Brooklyn… and there are other examples of this type of density in other neighborhoods, like Hunters Point, Jamaica and Long Island City.”

That dodged the question, which referred less to bulk than a concentrated population. I submitted a follow-up in writing: “My question referred to large real estate projects, like this one, with a projected 9000 units over 22 acres. What do you see as comparable?” They ignored it.2

Tortora’s response relied on the metric of Floor Area Ratio (FAR), or the amount of bulk compared to the underlying parcel. So they compared the amount of FAR enabled for specific parcels in area rezonings with Atlantic Yards as a whole, including the arena, open space, and demapped streets.

Downtown Brooklyn sites were rezoned to an FAR of 12. Again, those are individual parcels. In the AAMUP, buildings on Atlantic Avenue east of Vanderbilt Avenue can have an FAR of 10—and a height of 215 feet.

I estimated Atlantic Yards, as now proposed, would have an FAR at 10, or 11.5 not counting demapped streets.

By contrast, the two-tower Atlantic Yards Site 5 would have an FAR exceeding 25. The most comparable nearby parcel, The Alloy Block (formerly 80 Flatbush), with two towers, schools, and more, was rezoned to a 15.5 FAR.

Challenges in building fast

When would the first units be built, asked Simon.

McDonnell re-iterated that the developers’ plans to start on solid ground. “The ultimate timing and ultimate delivery of housing will actually have a lot to do with the staging of the platforms and how they’re built,” he said.

Faster delivery would rely on building the platforms in short succession. “But also you would have a significant amount of construction going on in a relatively small place all at once,” he said. “So there’s other negative knock-on effects of that.”

Affordable housing: rent levels

Raul Rothblatt, a longtime neighborhood activist, pointed to the developers’ AMI examples and suggested that they lower the affordable numbers, and also include senior housing.

(He mistakenly suggested that the median Brooklyn income was $47,000. Still, his point stands that Brooklyn median income—as of 2023, some $79,000, with household size unspecified—is below the figures used to calculate AMI, which rely not just on the five boroughs but wealthier suburban counties. So that’s $145,800 for a three-person household.)

McDonnell said he agreed with much of what Rothblatt said, but they’d relied “on the way that those [housing income] bands are typically described in housing policy.”

Given that much of the affordable housing built so far is geared to middle-income households, would more be at lower AMI levels? McDonnell, playing defense, noted that some units had been built at 160% of AMI, but they’d proposed a cap at 130% of AMI.

Unmentioned: due to rising AMI levels, rents for units at 130% AMI would exceed those previously rented at 160% of AMI, and it would be unrealistic to try to market 160% AMI “affordable” units, such as a one-bedroom costing about $5,000.

“We would intend to deliver average AMIs as well as a mix of AMIs that are lower than what was delivered previously,” he said.

That might not be too difficult, given that the record so far, as the four most recent buildings have affordable units only at 130% of AMI.

BrooklynSpeaks has advocated that the developer “provide the missing 1,031 moderate, low- and very low-income apartments from the existing approved project density.”

That does not appear to be on the table.

Affordable housing: who’s rent-burdened?

Given rising rents, McDonnell suggested that “folks who are experiencing rent burden”—paying more than 30% of their income on rent—shifted from the sort of bottom or lower income part of the income band, all the way up to professions that were traditionally thought of as as middle-income or workforce.”

That’s disingenuous. Even if moderate- and middle-income households face more of a squeeze, the AMI Cheat Sheet produced by ANHD, as association of nonprofit housing groups, consistently shows that the poorest are most likely to be rent-burdened.

Indeed, units at 130% of AMI can be close to market rate.

For example, while an income-targeted three-bedroom apartment at 130% of AMI could rent for $5,476, a market-rate three-bedroom nearby on Dean Street is listed for $5,500. (It’s not a new building with amenities, however.)

Affordable housing: lottery preference

Would the affordable housing offer a local preference for current residents or displaced residents, and for specific workers, like teachers, in the housing lottery?

McDonnell said there’s typically a local preference. Actually, just for housing subsidized by the city, not the state, with 20% set aside, declining to 15% by 2029, before the new Atlantic Yards towers open. (It used to be 50%.) Typically, 5% of city-subsidized units are reserved for city employees.

While BrooklynSpeaks has proposed community preference for those displaced from the area, arguing that they deserve promised but delayed affordable housing, the city hasn’t been receptive.

Affordability enforcement

How will ESD enforce affordability levels?

Kolkman said they could have “real requirements and milestones” in project documents, and that city or state regulatory agreements govern affordable units.

However, the project’s guiding Development Agreement generously defines affordable housing as participating in a city, state, or federal program limiting incomes and rents.

Only a revision could require specific income ranges, such as the ones stated in the 2005 Affordable Housing Memorandum of Understanding signed by original developer Forest City Ratner and the housing advocacy group ACORN.

Affordability: a Mamdani effect?

Would the project shift under the administration of new New York City Mayor Zohran Mamdani, given his focus on affordability?

Kolkmann noted the city had subsidized previous buildings. “So we certainly look forward to engaging with the new administration,” he said. “We’re three weeks in so, so nothing super definitive on that.”

Interestingly enough, Democratic Socialist Mamdani, when he was a longshot candidate nearly a year ago, filmed a video outside the Vanderbilt Yard, promising to "build 200,000 new, permanently affordable union built, rent-stabilized homes over the next 10 years, tripling what we're currently set to build."

Oddly enough, he didn’t mention Atlantic Yards, which I thought was a missed opportunity, even though it was/is too complicate to fit his template.

Affordability: displacement and lower incomes

Would future phases “exacerbate the continuing displacement of people of color from the neighborhood”?

Kolkmann said the issue would be studied in the environmental review, but that affordable housing was “a really important tool to mitigate that displacement.” (That depends on income levels.)

How many units could be built for “critical” lower-income levels, 40% to 60% in AMI?

“You can also bring more public resources to offset the total cost of the project,” McDonnell said. “There’s a push and pull in these things.”

He noted that the Atlantic Avenue Mixed-Use Plan, which offered increased density, promised 25% affordable units, at 60% of AMI, plus some 100% affordable buildings on publicly owned land.

Those sites, though, do not face the “extraordinary conditions” that Atlantic Yards has. (Well, that’s why the latter was approved to for far more bulk, and why the developers are asking for more.)

Affordability: consistent distribution of larger units?

McDonnell said he expected that the percentage of family-sized units promised, 20% to 30%, “would be fairly constant across income bands.”

That’s not the history of the project. Only after intervention by the city did original developer Forest City add two-bedroom units to the first tower, as I reported.

The four more recent buildings have no three-bedroom affordable units.3 Same with the first building. Currently, 360 of 1,374 affordable units, as per ESD’s chart below, are two- and three-bedrooms. That’s 26.2%.

The developers originally promised that 50% of the affordable units, in floor area, would go to family-sized units. That didn’t happen. Two “100% affordable” buildings, 535 Carlton Ave. (B14) and 38 Sixth Ave. (B3), have 35% family-sized units, by unit count.

Impacts of growth: school, shadows, wind

“With the 9000 additional residential units, where is the new school?”

As McDonnell noted, the project was approved for “roughly 6,400 units and a school was already built.” (They’ve proposed 2,570 more units on top of the 6,430 approved.)

The environmental review for the AAMUP, he said, suggested that schools in the area had sufficient seats, but the issue would be studied.

Would buildings block the sun?

Kolkmann said shadows would be studied as part of the environmental review. (Past answers have been: somewhat, but not crucial enough to prompt a redesign.)

How deal with currently high winds and avoid creating additional wind shear?

Wind, said Tortora, must be studied. “There are things we can do in terms of building positioning, as well as materials that we can use as part of the open space design that could mitigate any impacts.”

Impacts of growth: garden, Atlantic Avenue, loading docks

How “prevent negative impacts on the Pacific Street Bears Garden,” a tiny parcel at the tip of Site 5?

They aim to “mitigate the effect on the garden,” McDonnell said. “We still haven’t fully designed Site 5, so it’s hard to say… what those measures would be.” They’re committed to an ongoing dialogue with the gardeners.

How can they ensure an Atlantic Avenue safer to cross?

McDonnell noted that the city Department of Transportation is already studying various parts of Atlantic Avenue with respect to different public realm improvements. “We’re very interested in working with various interested stakeholders.”

Wouldn’t the buildings have loading docks, asked Rothblatt, who’d brought up the issue at the Dec. 8 workshop.

Loading and service issues will be part of the next stage of design,” Tortora said. “What you saw at the last workshop and what we presented today were really kind of high-level conceptual ideas.”

I had written that the developers do have a plan for a Site 5 loading dock on Pacific Street.

Impacts of growth: parking

“Will there be parking facilities for the public,” read White. “We have a parking issue as homeowners.”

McDonnell said yes; a traffic study would inform a parking plan.

In general, the city has reduced parking requirements and encouraged the use of public transportation, he said, “but this is a very dense area, and we would anticipate having some parking in the project.” That’s news.

The original Atlantic Yards plan did include parking under B5, B6, and B7, but that was later dropped, as shown in the second image below. Perhaps it might be restored at one of those parcels.

Contradicting the 2019 plan, below, ESD in 2021 agreed to eliminate planned parking at Site 5, which would instead contain retail space.

Given that construction is complete at parking at B3 (38 Sixth Ave.), next to the arena and under B14 (535 Carlton) and the southeast block, additional parking would require a new plan.

The phantom minor partners

White read a brief question: “What role do Greenland, USIF, and Fortress have in this project?”

She didn’t even explain the names. The U.S. Immigration Fund (USIF) brokered low-interest loans from Chinese investors to Greenland under the EB-5 investor visa program, and controlled the underlying lending entity as manager.

Fortress Investment Group, a longtime USIF collaborator, later acquired a piece of the debt. The collateral involved rights in entities known as AY Phase II Mezzanine and AY Phase III Mezzanine to build towers over the railyard.

However, control of that collateral was apparently trumped by Cirrus’s purchase of Greenland’s other debt, thus giving Cirrus control of the AY Phase II Development Company.

“Greenland was the largest provider of dollars to offset the expenses associated with the extraordinary conditions on this site,” replied McDonnell, noting that, by buying Greenland’s debt—excepting the EB-5 debt—“we were able to take control of the project, sort of put Greenland to the back of the line, and to move it forward.”

“USIF and Fortress were creditors of Greenland,” he said. “Greenland owed a lot of folks a lot of money, and they didn’t have any. There were many reasons for that. Part of it was COVID. Part of it was certain types of management. And you know, going forward, the project is owned and controlled by Cirrus and LCOR. Thank you for the question.”

That was not a complete answer. He didn’t mention how much USIF and Fortress would have a stake in project success. Previously, when I asked about ownership, I got the runaround.

Open space and community amenities

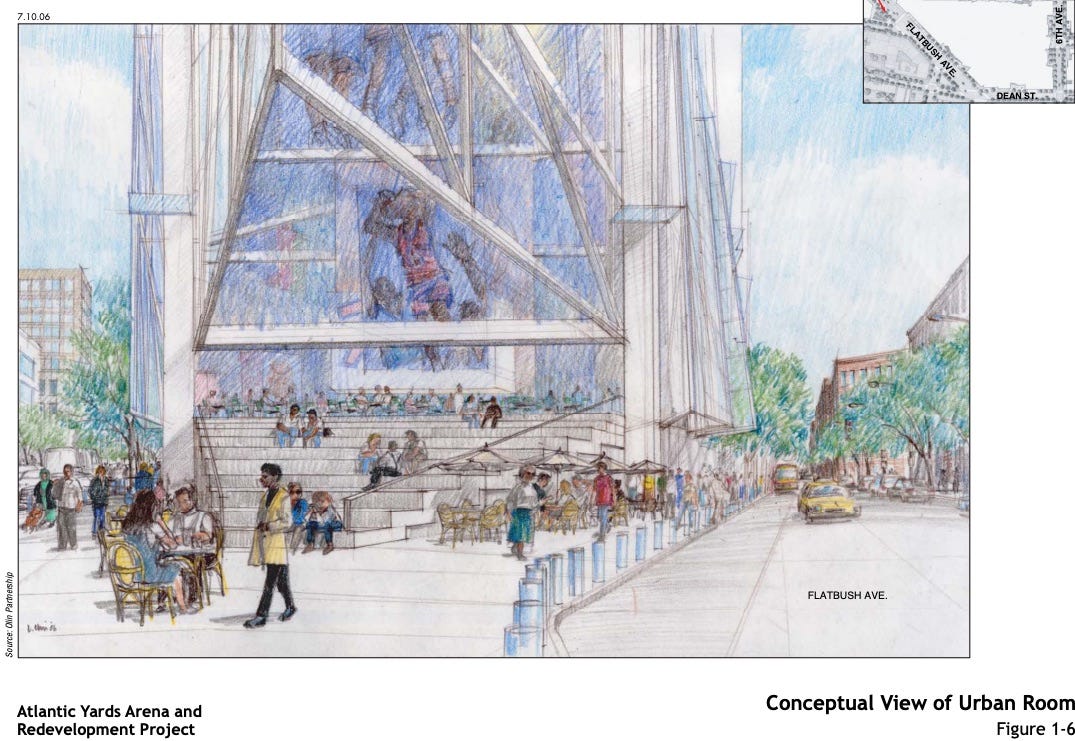

What about the promised Urban Room, the atrium once planned at the base of the B1 tower, and how would community spaces will be respected? (That reflects a BrooklynSpeaks question, as linked in the footnotes.)

McDonnell said, “We’ll be looking to program gardens, rain gardens, various other outdoor public spaces which hopefully have the right programming and activation to make them both sustainable and useful to the community.”

They also plan “community facility landing points on the first floors, such as the promised Intergenerational Center.

The Pacific Park Conservancy and open space

Would the New York City Parks Department be involved in the development and maintenance of the project’s open spaces?

No, said Kolkman, given that it’s a state project.

He cited the Pacific Park Conservancy, controlled by the building owners, which has seats on its board for the Parks Department and local Community Boards.

Those, however, have mostly not been filled. The Conservancy is something of a phantom, I’ve written, with no website or public board meetings.

Will the Conservancy be made more accessible to residents?

McDonnell said Cirrus and LCOR—which presumably now control the Conservancy—have since retained Town Square to manage the current open space as well as the sidewalks around the railyard.

He also promised a phone number and email to contact Town Square, “and concerns or complaints can be directed to the appropriate folks, whether it’s the Conservancy, whether it’s the developer team. So look for that in the short future.”

Who’s responsible for managing snow removal on sidewalks?

McDonnell said it would be Town Square. Snow clearing at Site 5 is the responsibility of “currant tenancy,” i.e., P.C. Richard and the Brooklyn Basketball Training Center. “So I would anticipate no problems this weekend.”

Could arena operator be forced to pay?

White read a clipped question that deserved more explication: “Could [arena operator] BSE Global fund a Quality of Live [violations] enforcement unit? Could other benefits be extracted?”

Kolkmann responded noncommittally: “You know, BSE, obviously, is an important part of this project and important stakeholder, and we look forward to discussing how their role in the project can continue to evolve as we move forward in developing this plan for the rest of the sites, and going through that public review process.”

The question White read reflected an ask raised previously by BrooklynSpeaks, which cited impacts of arena events. (Curiously enough, it was not articulated in their pre-workshop advice, as listed in the first footnote.)

I had raised a broader question, which explained the rationale: Since not building the B1 tower and preserving the Barclays Center plaza—creating that giant, two-tower project at Site 5—helps the arena operator accommodate crowds and monetize advertising, can/will ESD seek any payment?

BSE Global, now Brooklyn Sports and Entertainment, is a huge financial winner from the state-enabled project. It’s simple fairness for the state to revisit its deal and have the arena operator share its gains, as I’ve argued.

To stave that off, might BSE volunteer a small contribution; endow a public amenity on Site 5; or offer more scholarships to its profit-focused Brooklyn Basketball Training Center?

MWBE questions

What are the opportunities for MWBE businesses and small businesses?

Kolkmann said that, as with any ESD project, it will be subject to the state’s minority- and women-owned business enterprise subcontracting requirements, typically 30% of the eligible costs.

Tortora said Cirrus has partnered with the Building Trades Employers Association’s MWBE program to involve such firms.

He said they’re also considering how ground floor retail space can be conducive to smaller storefronts, “which tend to work for local businesses.”

Climate change and geothermal

Prospect Heights resident Alan Rosner, who two decades explored the project’s terrorism vulnerabilities, noted Atlantic Yards would involve “an enormous use of energy, and there’s no addressing any issue of climate change.”

At the previous workshop, said Rosner, he’d asked about a feasibility study for a wide area networked geothermal system, or heating and cooling from the ground.

“There are benefits not just to the developer, but for the community,” he said.

“We’re exploring a variety of sustainability practices in line with our policies,” Tortora responded, noting LCOR’s experience in delivering such a system. (It at a tower in Coney Island.)

“So it’s definitely something we’ll be looking into,” he said, without making a commitment. One threshold question may be whether the site’s challenges, including the railyard, make it a better or worse candidate.

As shared by BrooklynSpeaks to its email list:

If the State chose not to collect damages from the developer for missing the May 2025 affordable housing deadline, why isn’t the State guaranteeing the payments so the City can create much-needed affordable apartments now?

Will the new development team be required to provide over 1,000 low- and very low-income apartments promised under the original plan but not delivered?

Why has the new development team set the income targets for additional affordable housing at the project from 80-130% of Area Median Income ($116,640- $189,540 for a family of three)?

How many of the 2,600 apartments the team wants to add will be affordable?

Who will design and manage the project’s open space, and how will they be accountable to the public?

What will be done to provide the indoor public gathering place promised under the original plan?

How will the public and its elected representatives be involved in approving the new plan?

What does ESD plan to do differently to improve accountability and transparency so mistakes of the past that have led to delays in public benefits aren’t repeated again?

The first half of Hudson Yards was rezoned to a higher density, but has a limited amount of housing. The second half would have 4,000 apartments over 13 acres, or about 308 apartments per acre.

Only one, 18 Sixth Ave. (B4, aka Brooklyn Crossing), has three-bedroom market-rate units.