Who Controls the Arena Plaza? New York State's Explanation Left Something Out

Complex transactions involving the (unbuilt) flagship tower and the Barclays Center operator were envisioned. Shouldn't BSE Global pay to gain a permanent plaza?

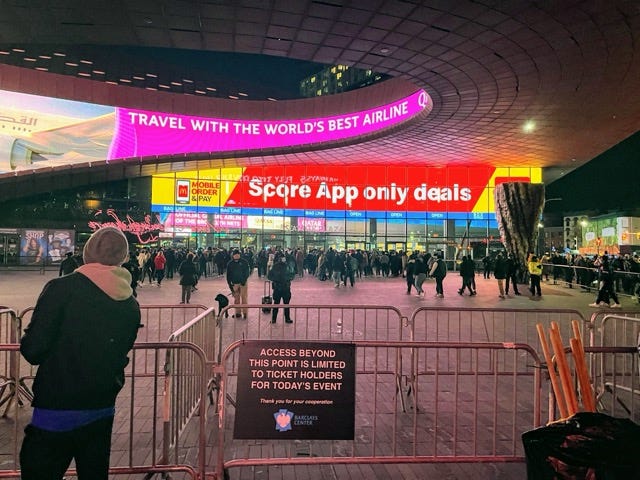

So, who exactly controls the Barclays Center plaza, branded Ticketmaster Plaza? It’s a key question, as new plans for Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park emerge, with both the developer of new towers and the arena operator, BSE Global, all seeking advantage.

According to Empire State Development (ESD), the state authority that oversees/shepherds the project, BSE Global’s in charge.

That suggests ESD couldn’t push BSE, owned by billionaire Joe Tsai (and the Koch family) to pay to ensure that the temporary plaza becomes permanent.

The BrooklynSpeaks coalition aiming to improve the project, has suggested the arena fund a publicly operated quality of life enforcement unit addressing arena impacts. I think BSE could pay even more.

However, it's more complicated than what was stated at the Sept. 26 meeting of the advisory Atlantic Yards Community Development Corporation (AY CDC), as I describe below.

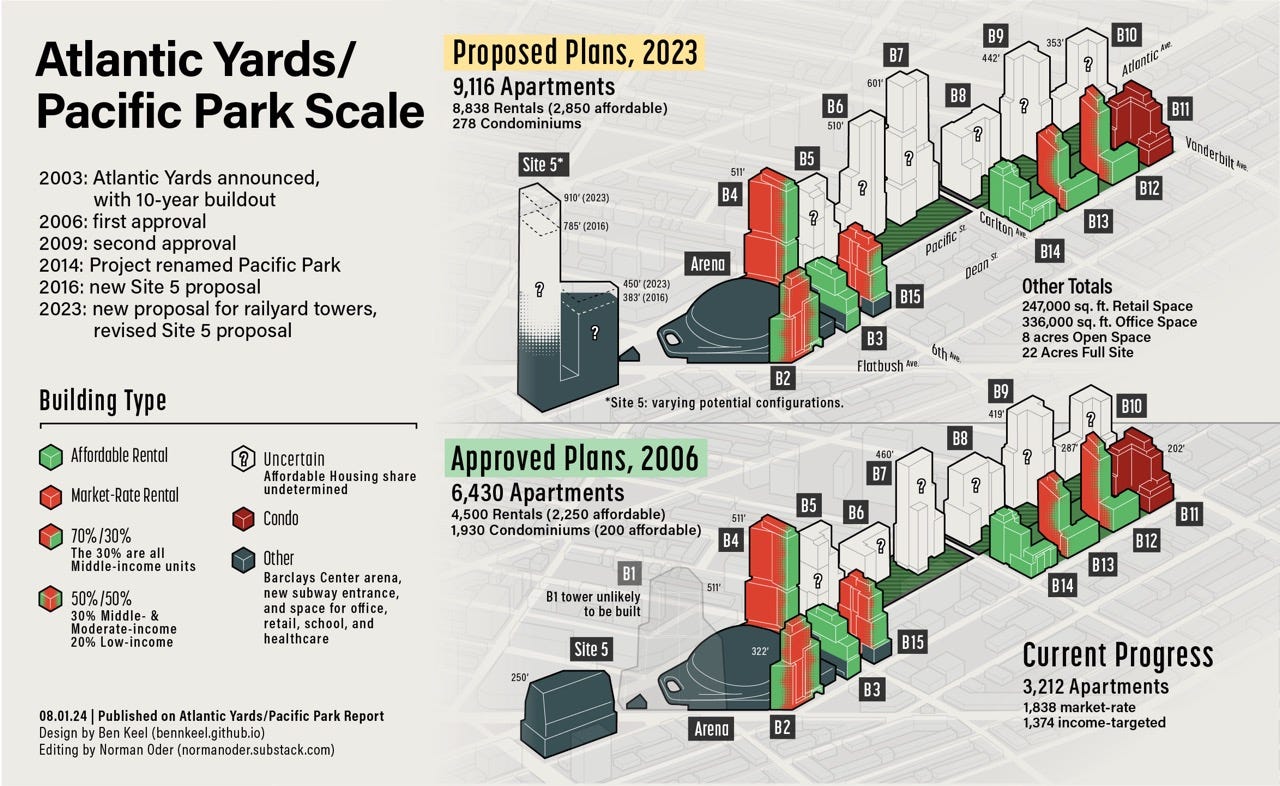

Bottom line: the public has more leverage regarding a pending plan to make that plaza permanent by shifting the bulk of B1, the unbuilt tower long slated to loom over the arena, across Flatbush Avenue to a parcel known as Site 5, creating a giant, two-tower project.

Both the B1 parcel and Site 5 are, for now, controlled by Greenland USA, the master developer, succeeding original project developer Forest City Ratner.

The latter, which once planned to build the arena and four flanking towers at the same time, during the recession chose to build a smaller arena, decoupling the towers. Three of the four parcel sites, but not B1, would be relatively easy to build on.

Greenland is separately losing control of the six development sites (B5-B10) over the Vanderbilt Yard. A “preferred developer” for those sites may emerge at an AY CDC meeting Thursday.

The discussion

The Sept. 26 discussion (video here) was led by Anna Pycior, ESD’s Senior VP for Community Relations. Responding to an AY CDC request for more information about the plaza, she said, "The blue portion of the map in the slide represents the public plaza,” adding that BSE’s lease requires it to maintain and repair the plaza.

I think she meant the blue portion that extends from the arena's front doors to the tip of Atlantic and Flatbush avenues, since the rest of the blue encompasses the arena, plus an extension to from the loading dock south on Dean Street and a small rectangle east to Sixth Avenue at Pacific Street.

I don't have the arena lease, but I did check the March 4, 2010 Declaration for the arena site, which ESD lawyer Matthew Acocella cited at the meeting as governing construction of B1.

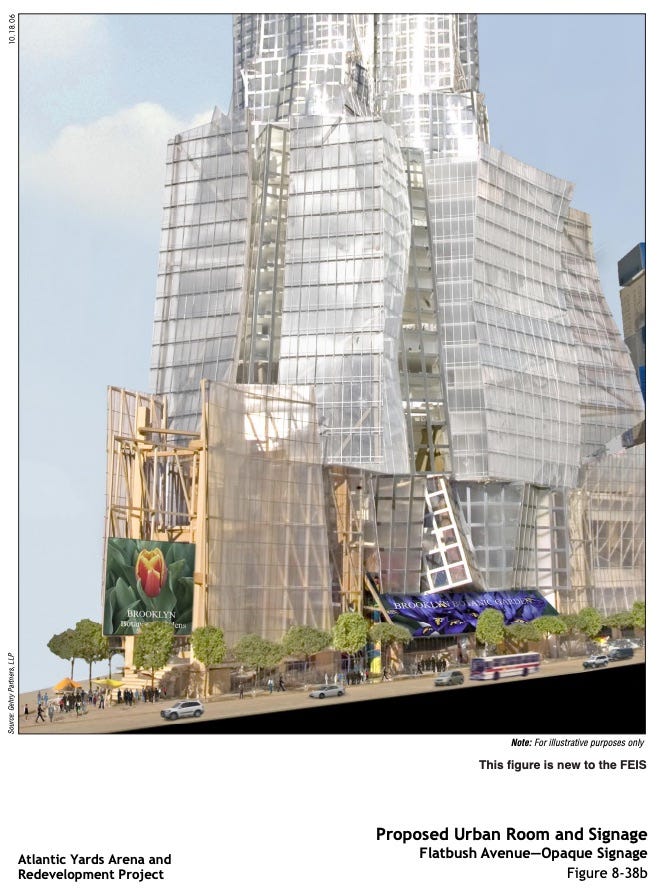

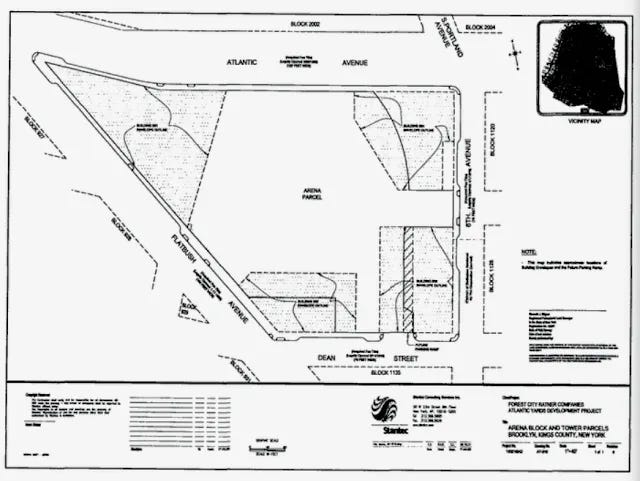

That document adds complication. The last page of the Declaration, part of Schedule 3, contains the graphic below. The triangle at the western end is labeled “Building One Envelope Outline.” So B1, not the plaza.

However, it’s not three-dimensional. According to Schedule 1 of the Declaration, the B1 parcel is 55,379.32 square feet or 1.2713 acres, but it starts at a horizontal plane at an elevation of 198.7 feet.

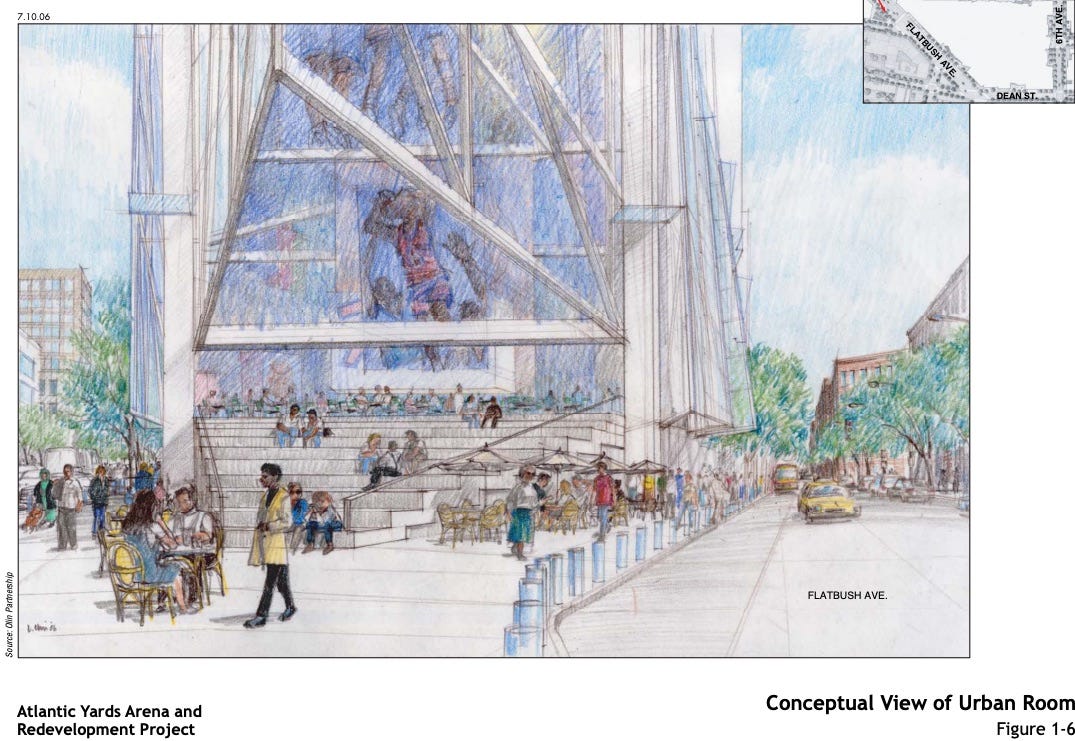

That would allow for an atrium (below) known as the Urban Room, which was once slated to house entry to not just the arena but also the office tower above and the transit hub below.

So that conflicts with a permanent plaza. I’ll discuss the Declaration further below, but let’s go back to an exchange at that AY CDC meeting.

The discussion

"Okay, but at some point, if they build a building there, it can't be part of [the arena] lease any longer," said AY CDC Director Gib Veconi. Indeed, as described below, the area for B1 had, in 2012, been severed from the ESD-owned non-arena parcel.

"[The arena company] would still have the ability to use and maintain and improve and program the enclosed space under the construction," Acocella said, referencing the Urban Room. Unmentioned: that would’ve been below the plane of the B1 parcel.

"So effectively, the economic value to them of relocating B1," Veconi said, "is not to lose access to that space for the intervening years where the B1 building would have been developed."

Indeed, construction would interfere hugely with the ability to manage arena crowds, promote sponsors like Ticketmaster (hence Ticketmaster Plaza), and use digital signage—in the arena oculus, as well as an LED “wall” over front doors—for advertising and promotional purposes.

Moreover, the Urban Room couldn’t be a complete substitute, since it would offer less space for arena use.

Veconi suggested a license agreement probably "explains what would happen when that construction takes place. There's presumably some economic value to them, in having that not happen."

"I can't speak to the economic value," Acocella replied, sounding lawyerly. "The Declaration does speak of what would happen when they're ready to proceed with construction of B1."

"Is there any relief in the lease expense for Brooklyn Sports and Entertainment during that time, if that happened," asked Veconi, "or do they still pay the same?"

"No, nothing changes," Acocella said.

Big savings

That might have been time to explain that the arena lease expense, in terms of payment to the state, is essentially nil: $10/year.

Were B1 constructed, the builder of that tower would have had to pay relief to BSE Global, as explained below. So, by moving that bulk across the street, Greenland (or its successor) gains that savings.

More importantly, it would save the developer, as Greenland USA President Gang Hu wrote in an August 2022 letter to ESD, a challenging construction term of seven to eight years, far long than the 35 months once estimated in state documents.

Not only would BSE Global avoid an awkward, frustrating situation for arena patrons and sponsors, it would avoid sharing the arena’s loading dock with the B1 owner, as originally planned. (The B1 occupant would pay a pro rata share of expenses.)

Win-win, right?

Well, perhaps not for Site 5’s immediate neighbors on low-rise Pacific Street, facing, for example, a loading dock serving two large towers. At some point the scale of Site 5—as pending, far larger than approved in 2006—makes for a very tight fit.

What if B1 were built?

If the B1 occupant became ready to build the tower and to modify the plaza (formally known as the “Urban Experience”) into the Urban Room, it would have to supply a Construction Notice detailing its plans, according to the Declaration.

Within 30 days, it the arena operator would identify a location for a temporary box office and other arena facilities, and could request the B1 occupant to prepare such plans. The B1 occupant would be responsible for building those temporary facilities.

The B1 occupant couldn’t start building the tower or converting “the Urban Experience into the Urban Room” until the temporary facilities were complete.

Would construction be a mess? The B1 developer should “use commercially reasonable efforts to minimize disruption to the use, operation and maintenance of the Improvements on the Arena Parcel,” according to the Declaration. That phrase, a judge observed in 2010, was so vague as to be essentially unenforceable.

The B1 occupant would have a permanent easement to reach the office building through the Urban Room. So to would the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, for access to the subway hub below.

Revenue for the arena

The arena company would still reap revenue from the Urban Room.

It could choose a location for a box office and related uses (café, restaurant, retail, and more), could license the naming of the Urban Zone (the umbrella term for the Urban Experience and the Urban Room), could maintain signage there, and could “retain all other economic interests derived from the Urban Zone” not granted to the B1 occupant.

That’s not insignificant. However, as I’ve argued, the plaza—the current “Urban Experience”—offers far greater revenue and promotional options, given its open-air nature.

The arena operator would still have to maintain and repair the Urban Zone. The B1 occupant would have to pay the arena company a share of maintenance and utility costs.

Revenue for the B1 owner

Greenland and its successors gain enormously by not building B1 as approved. First, they avoid the complex challenge of building a tower over a working arena. It would take less time to build at Site 5.

Moreover, an Interim Lease for the Site 5 parcel signed in 2021, memorializing the transfer of bulk from B1 to Site 5, suggests new revenues beyond the significant value of the bulk transfer. (In 2022, I estimated the bulk was worth about $300 million, at least before adjustments for below-market housing.)

For example, it would allow the Site 5 developer to build a 550-room hotel, to swap below-grade parking for retail space, and to install dynamic LED signage.

So, rather than have either the B1 occupant or the arena occupant gain revenue from signage, as was originally contemplated, now both could gain revenue from signage.

Now what?

On Feb. 28, 2012, according to the First Amendment to Memorandum of Interim Lease, ESD severed the B1 parcel from the arena block.

That meant the tenant, the Forest City-owned Atlantic Yards Development Corporation, controlled the parcel. On the same day, a Memorandum of Agreement of Development Lease between those two parties summarized provisions in the (unreleased) Development Lease.

Those development rights were later inherited by Greenland, as it took over ownership from Forest City.

Today both Greenland and BSE Global have an interest in the B1 bulk getting moved to Site 5, and the plaza being made permanent.

For ESD and New York policymakers, this should prompt not passive acceptance but an active policymaking. Do private benefits mean increased public costs and impacts?

Don’t the Site 5 (and project) plans deserve broader analysis (as suggested by BrooklynSpeaks and me), including the importance of reciprocal public benefit?