New Developers Seek to Supersize Project: Total 9,000 Units, Instead of 6,430. Taller Towers (and One Subtraction) Allow More Open Space

1.6M more sq. feet (value: $320M?) sought, said to make project & affordability viable, but low-income units not priority. Changes could mean faster buildout. Would bulk increase be just 20%? (Nope.)

A public workshop yesterday, sponsored by Empire State Development (ESD), was billed as soliciting public input on height, density, and affordability of the remaining Atlantic Yards project, nearly 22 years—and much frustration and mixed feelings—after the project was announced.

The big news, though, came when the development team finally revealed its plans for a significant expansion—which would’ve been far easier to assess had they been shared ahead of the workshop.

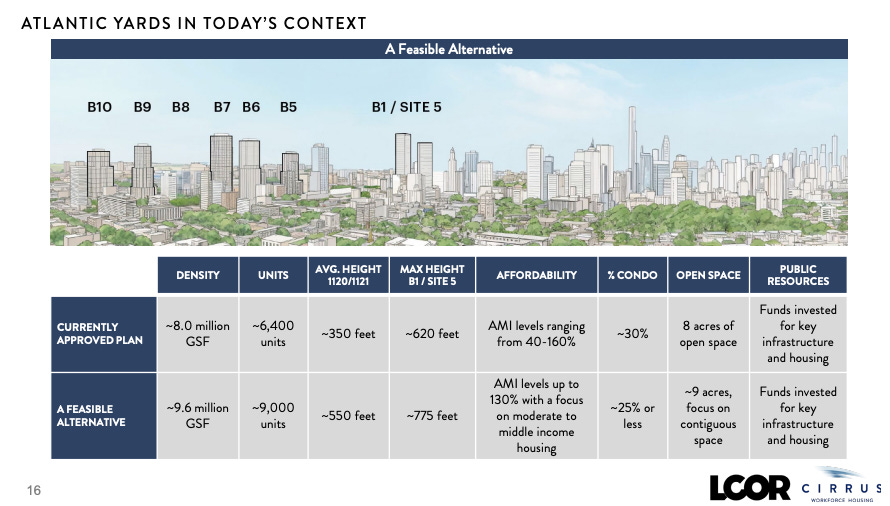

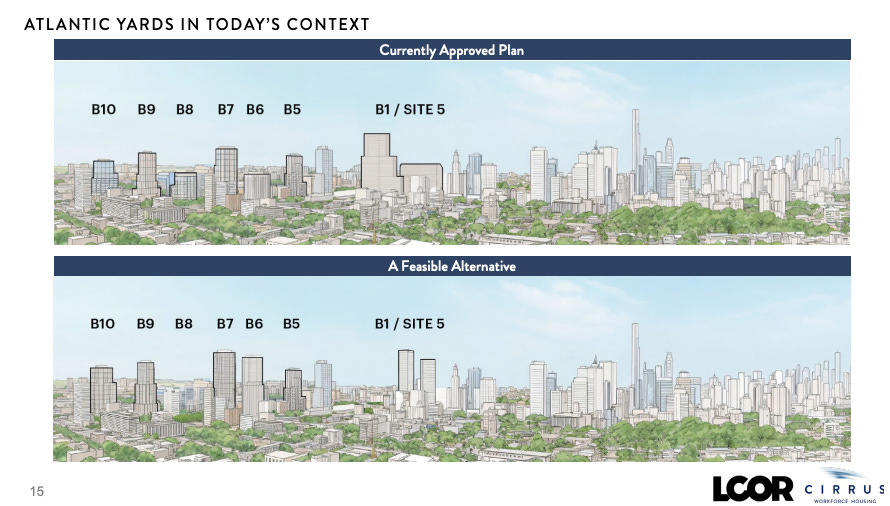

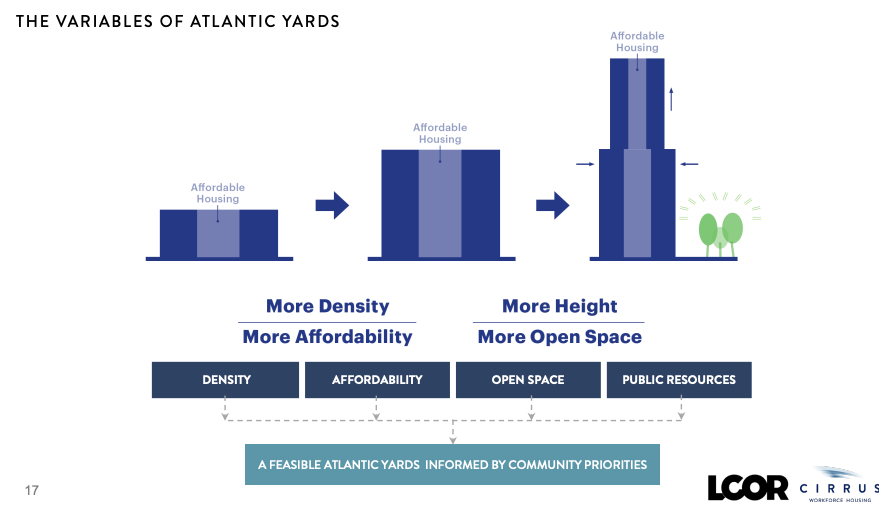

Presenting what they called “A Feasible Alternative,” they proposed to dramatically expand the project, citing cues from Downtown Brooklyn (which is not Prospect Heights but nearby) and with:

five taller buildings averaging 550 feet (rather than 350 feet) over the two-block railyard, which requires an expensive platform

1.6 million more square feet of bulk, a purported 20% increase (but not exactly; see below)

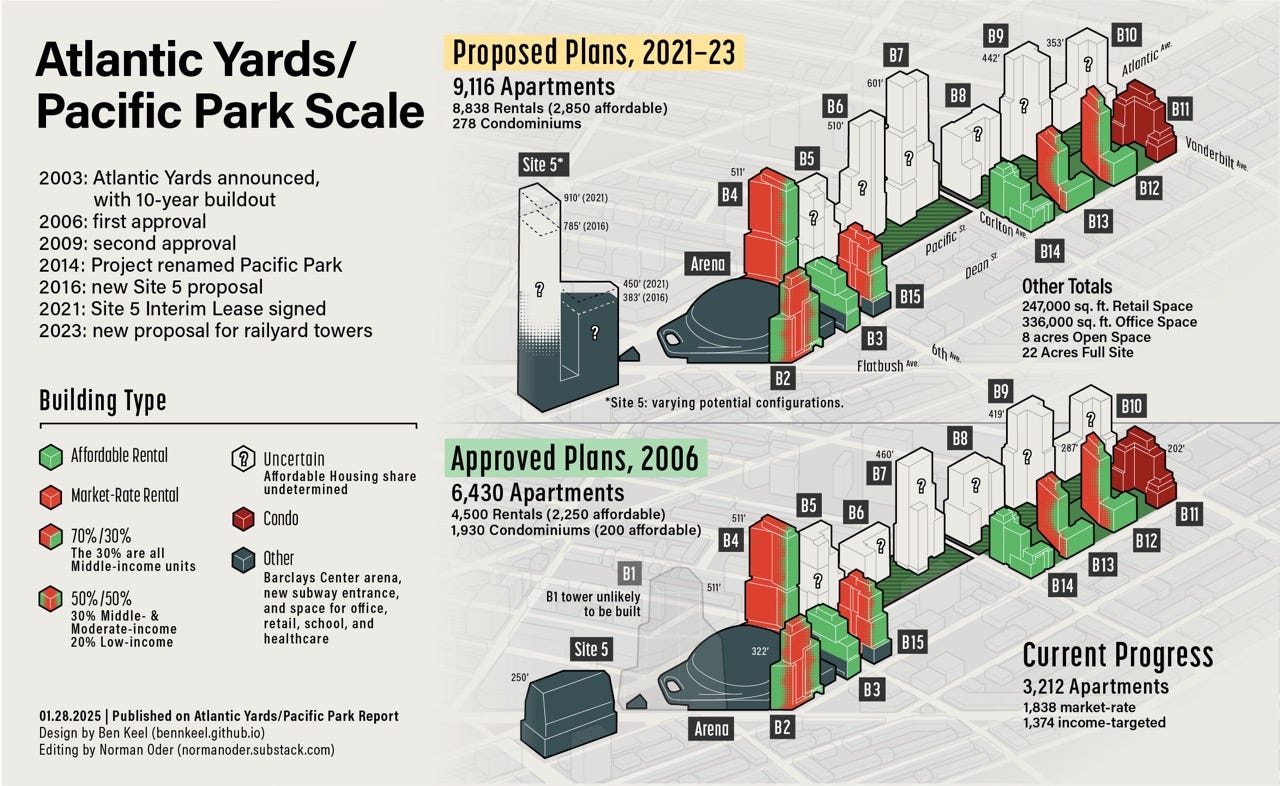

and some 9,000 apartments, 2,570 (or 40%) more than currently approved, leaving a total of 5,788 left to build, given 3,212 units completed

The key information was shown on screen but not in the handout for attendees. The presentation was posted online this morning after 10 am. At bottom, see videos of the three main presenters.

Affordability issues

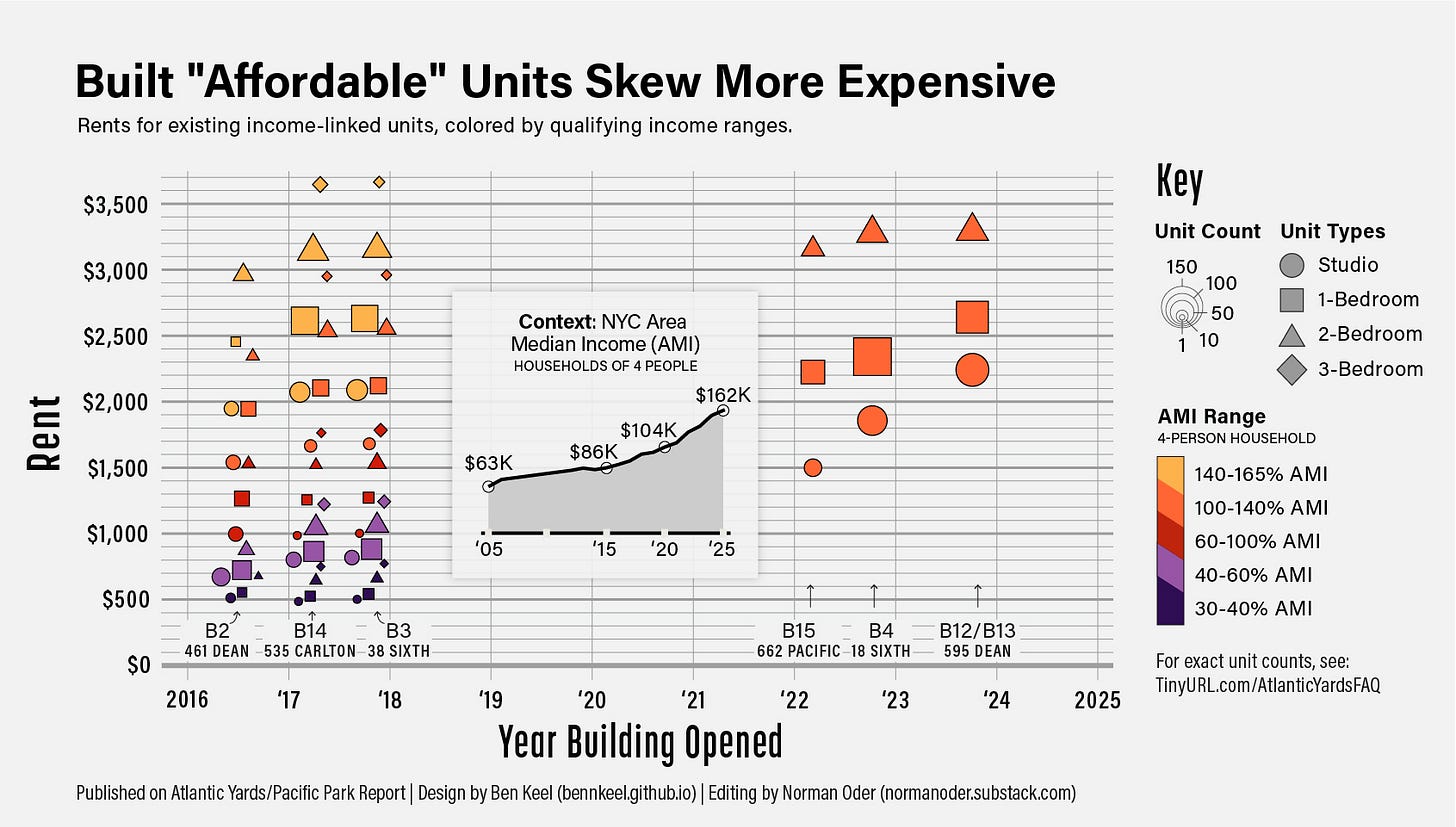

Note the focus on “moderate to middle-income housing,” over 80% of Area Median Income (AMI), which excludes low-income housing, a key deficit in the project.

While Gib Veconi, a key organizer of the BrooklynSpeaks coalition, praised the development team as “upfront about their vision for density and affordability,” even without specifics “it was quite clear to me that the stated focus on 80-130% AMI does not align” with the affordability level of private rezonings or the recent Atlantic Avenue Mixed-Use Plan, ”which I regard as a barometer for what the public and its elected representatives could be expected to support.”

How it might work

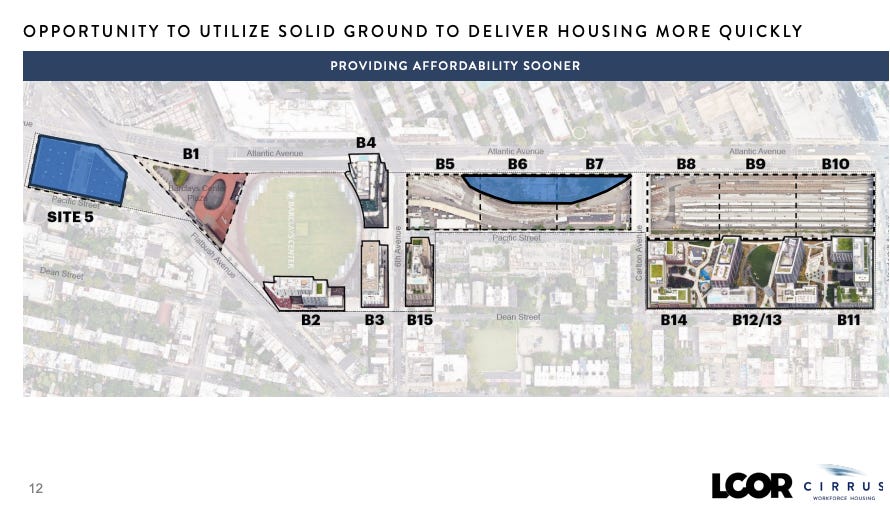

Part of the increase in unit count would come from the additional bulk, the rest from deploying bulk previously approved for potential commercial use at the parcels known as B1 (the tower slated for what’s now the arena plaza) and Site 5 (the site across from the arena home to P.C. Richard and the former Modell’s site, now the Brooklyn Basketball Training Center). The meeting was at the latter venue.

Taller, thinner towers might be advanced thanks to a focus on terra firma sites, as well as using the platform foundations that previous developer Greenland USA already built.

All this, said representatives of the joint venture involving funder Cirrus Workforce Housing and the development firm LCOR, would make a complex, expensive project viable, built faster, and with better open space—notably an additional acre separate from any buildings, at the former site known as B8.

The image above, in the bottom half of the screen, proposes far taller buildings than approved in 2006 (and re-approved in 2009), though specific heights were not indicated. That said, the taller of the two towers at Site 5 would be 775 feet tall; the shorter tower appears to be not much shorter.

It looks, from an eyeball view, that the B6 and B7 towers might be nearly as tall as Site 5, though the five railyard towers would average 550 feet.

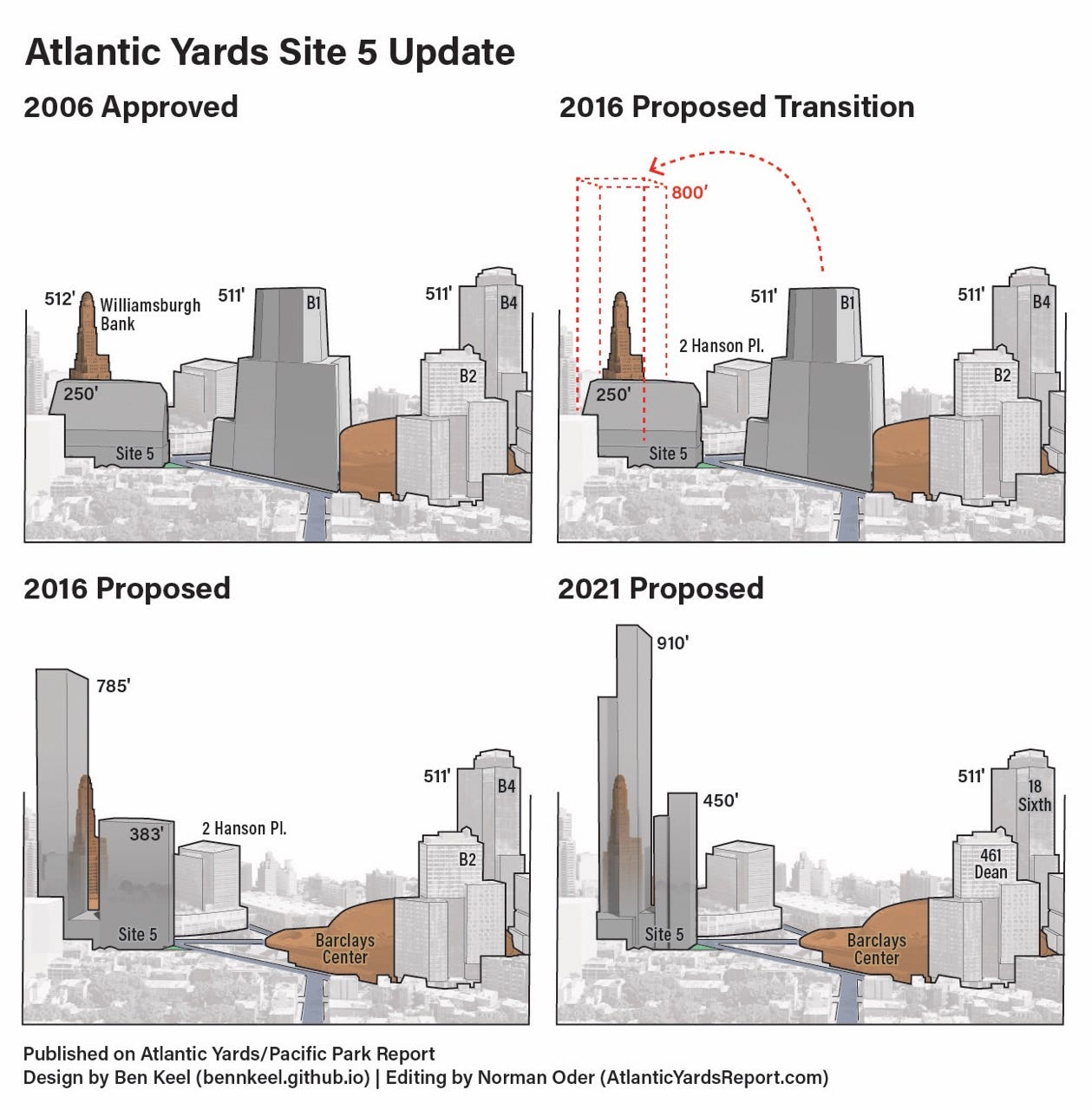

ESD in 2021 agreed to support a plan for two towers at Site 5, one 910 feet tall and the other 450 feet. See image below. Are the new developers splitting the difference?

The big picture

Bottom line: they propose more units, likely including more affordable ones, and more open space, with the trade-off additional bulk and height (and unspecified public concessions). The response was a mix of wariness and welcome, from the mix of people I preliminarily canvassed.

It seemed that ESD, the gubernatorially controlled state economic development authority, is on board, and the exercise aimed at tweaking the “feasible” plans proposed by the developers, not analyzing their feasibility or alternatives. Due to state control, ESD overrides New York City zoning requirements and affordability requirements.

The scale does reflect a changing Brooklyn and in some ways echoes the Domino Sugar megaproject in Williamsburg, in which taller buildings were proposed to deliver more green space.

That said, the latter has the advantage of its open space fronting the waterfront, not a major road, so issues of urbanism and what advocacy planner Ron Shiffman calls the “carrying capacity” of the site remain to be addressed.

Also, the development team left vague the “public resources” expected, describing it as “Funds invested for key infrastructure and housing.” That might—which could include support for the platform—deserve analysis by third-party experts.

“They seem to be committed to doing affordable housing, workforce housing, and to actually building it,” said Assemblymember Jo Anne Simon, a leader in the BrooklynSpeaks coalition, after the event. “And I think that’s a big change from the past.”

“The fact that they’re doing more density, it’s not something I’m thrilled with, but it’s something I recognize is the only way they’re going to build,” Simon said. (Then again, note “Three cheers for more housing!” from project neighbor Sean Sullivan, a YIMBY take.)

Simon said she had not yet learned of requests for additional subsidies and concessions. There was no discussion yet of any new accountability mechanisms to ensure that promises are fulfilled. (Or, for that matter, of such benefits as LED signage at the Site 5 parcel.)

The proposed bulk increase partly echoes a plan floated in 2023 by previous master developer Greenland USA to rescue the project by building, as I calculated, more than 9,100 total apartments, before losing control in a foreclosure process.

A 20% increase in density?

While McDonnell described a 1.6 million square foot increase in bulk, from 8 million square feet to 9.6 million square feet, as a 20% increase in density, that’s a narrow and misleading way of looking at it.

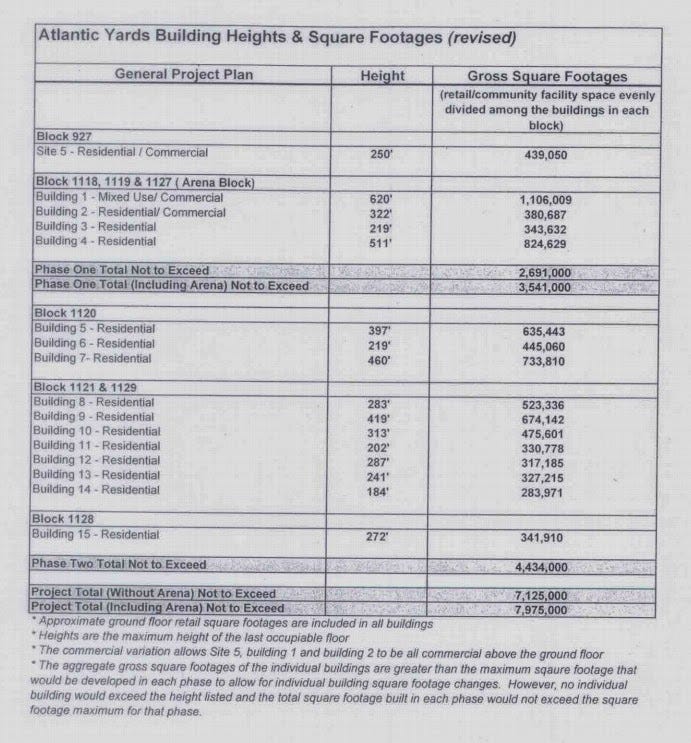

First, that 8 million square foot total included the arena, as shown in the image below. The tower bulk was limited to 7,125,000 square feet. Add 1,600,000 square feet and that’s a 22.5% increase in tower bulk.

Based on the chart above, from ESD, going building by building, I calculate 3,150,637 square feet built, with 5,032,451 approved square feet remaining.

Add 1.6 million square feet, a 31.8% increase over the remaining bulk, and the total to be built would be 6,632,451 square feet. That’s more than twice the bulk of what’s already built.

Subtract the bulk allotted to Site 5 and B1 from the total remaining, before any increase, would leave 3,487,392 square feet over the railyard.

Add 1,600,000 square feet to the 3,487,392 square feet approved for the railyard sites translates into a 45.9% increase in bulk, to 5,087,392 square feet.

(Note: the numbers are rough, because the chart above is imprecise, and some bulk from B1/Site 5 likely will be re-allocated to the railyard. However, it’s not a simple 20% increase.)

Affordability pending

The new joint venture didn’t propose a total number or affordability level of future below-market apartments but said they aimed to build at all income levels, “across the affordability spectrum.”

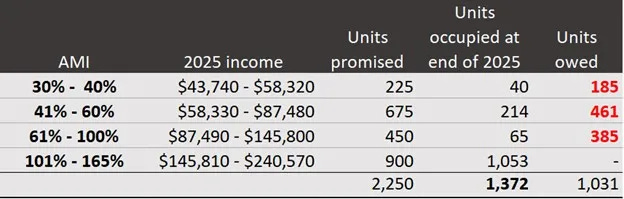

While BrooklynSpeaks has advocated that the developer “provide the missing 1,031 moderate, low- and very low-income apartments from the existing approved project density,” that’s not yet on the table.

“Deeper affordability is the largest priority,” said Council Member Shahana Hanif after the event. (Also present: state Sen. Jabari Brisport.)

That trade-off is said to be shaped by public input, but if the number were consistent with the 35% previously pledged, that could mean a total of 3,150 affordable units.

That would mean 900 more total affordable units, given 2,250 previously approved, and 1,776 remaining to be built. That said, deeper affordability might mean fewer income-targeted units.

130% AMI ceiling no sacrifice

The developers set a ceiling for income-targeted “affordable” units at 130% of AMI, rather than 160% of AMI, as in past buildings (and in the otherwise unmentioned Affordable Housing Memorandum of Understanding, signed with the advocacy group ACORN in 2005).

That said, it wouldn’t be a huge sacrifice. Consider that the last three Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park buildings had affordable units at 130% of AMI but, in several cases, had to lower the rents below allowable limits to attract tenants.

Rising AMI means ever-rising baselines for income-linked housing. Consider, under 2025 guidelines from the city, units at 130% of AMI could rent at these monthly levels, which literally would be off the above chart:

Studio: $3,685

1-BR: $3,948

2-BR: $4,738

3-BR: $5,476

By the time new buildings open, the baseline will have risen even more.

Fewer condos, but…

The project was approved with 1,930 expected condos out of 6,430 units, or 30.4%. The new developers pledged not to build more than 25% condos.

While that in some ways sounds better—Cirrus principal Joseph McDonnell again contrasted their firm with developers focused on condos—it still leaves a significant number left to build.

Consider: out of 9,000 projected apartments, at 35% affordability, 3,150 would be below-market. That would leave 5,850 market-rate units. Of that, 25%, or 1,463, could be condos. Subtract the 278 condos already built in the 550 Vanderbilt tower; that would leave 1,185 condos left to build.

More open space

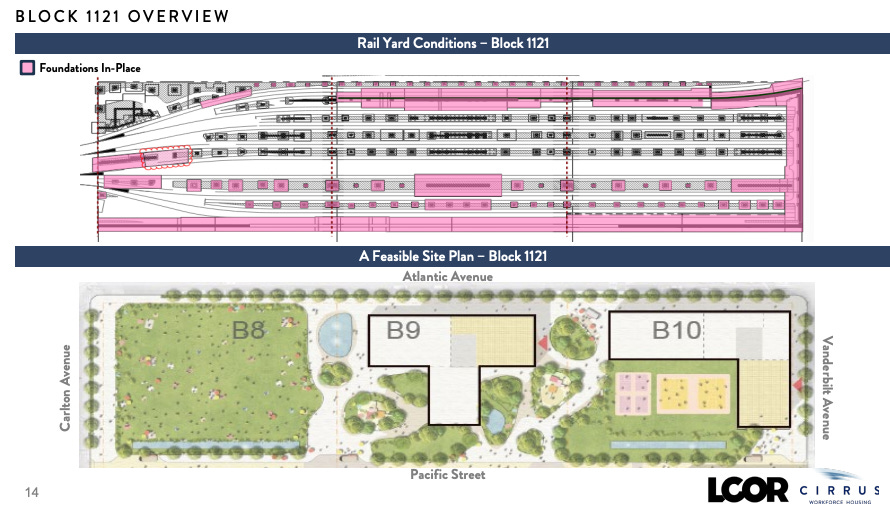

Crucially, the developers promised an additional acre of open space, east of Carlton Avenue over the eastern block of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s Vanderbilt Yard, at a parcel previously designated B8.

That would deliver a more public gathering space, rather than be seen as a courtyard for building buildings, a “more contiguous and thoughtful program,” in the words of McDonnell. That responds to longtime criticism of the open space design, initially from the Municipal Art Society and later BrooklynSpeaks, as seeming too private.

The new open space segment also would help the developers avoid the knotty issue of building over complex railyard functions, where Long Island Rail Road trains are stored and cleaned. (Greenland had still planned to build B8.)

“Due to the convergence of the storage tracks [see image] and critical MTA infrastructure that are located at the western edge of the site,” said LCOR’s Anthony Tortora, “B8 is so complex [that] our idea is to eliminate a building on B8 altogether, reallocate that density elsewhere and deliver B8 as a park amenity.”

One note: the area is notably windy, so towers could exacerbate that. Regina Cahill, a 50-year resident, observed that the children’s playground already on the project open space “is uninhabitable on windy days.”

Building quickly

The timing for the project remains unclear. It would require a formal re-approval process by ESD, the state agency that oversees/shepherds Atlantic Yards, likely starting next year.

The developers said they would aim to build quickly on the easier parcels. That includes Site 5, which would combine the bulk approved for that site plus that of B1, which would be difficult to build over a working arena.

Unmentioned: that bulk transfer also would give the arena operator, BSE Global, a huge benefit by making the temporary plaza, now sponsored by Ticketmaster, permanent.

BrooklynSpeaks suggests that BSE Global should, in exchange, be required to pay for an unit to monitor quality-of-life violations related to arena operations. I think they could be asked to pay for more.

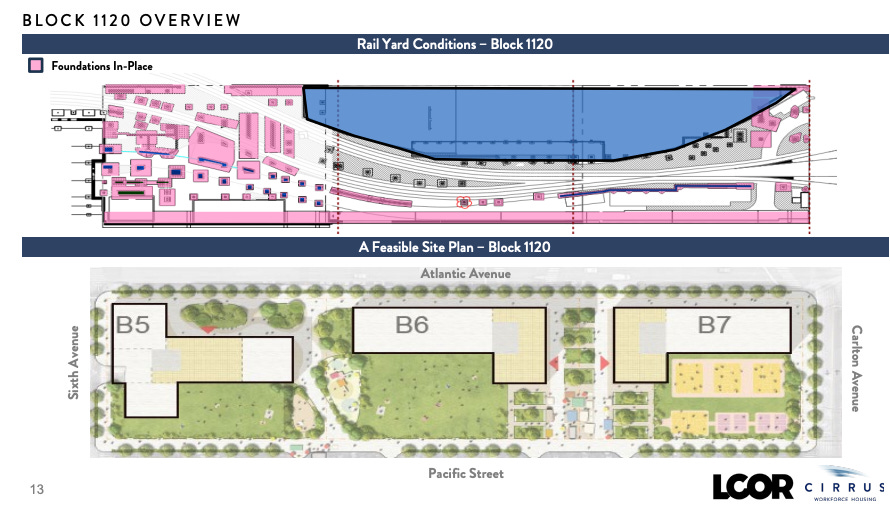

Notably, the B5 site, just east of Sixth Avenue between Pacific Street and Atlantic Avenue, already has significant platform work completed. The platform protects the railyard, used to store and service Long Island Rail Road trains.

Taking a cue from Greenland, the new joint venture has revised the design of the B6 and B7 towers, on the railyard block between Sixth and Carlton avenues, to make them narrower.

That would allow them to build on the limited amount of terra firma, once home to at-grade buildings, jutting south on Atlantic Avenue. That’s considerably easier than building over the active tracks, which instead would support the new open space.

They also would take advantage of the significant investment that Greenland already made in preliminary platform work.

It’s farther ahead on Block 1120, the first railyard block, between Sixth and Carlton avenues, than on Block 1121, between Carlton and Vanderbilt Avenues. The north-south borders are Atlantic Avenue and Pacific Street.

Taller buildings

Previously, the project’s tallest building was to be the B1 tower slated to loom over the arena, approved at 620 feet—though original developer Forest City Ratner, in a concession to critics, promised to limit the height to 511 feet, one symbolic foot lower than the Williamsburgh Bank Building, long the borough’s tallest.

Now Brooklyn has a “supertall,” over 1,000 feet, and other buildings far taller.

The B4 tower at 18 Sixth Ave., known as Brooklyn Crossing, is 511 feet, currently the tallest.

The tallest building over the railyard would’ve been 460 feet, with the six buildings averaging 350 feet.

They’re proposed to average 550 feet or, as McDonnell pointed out to me, about 450 feet if you count the missing building at B8.

Value of concessions

The concessions already sought, 1.6 million square feet in additional buildable square footage, might be roughly valued at $320 million, at a ballpark $200/buildable square foot (bsf).

A 2024 report on the Brooklyn market from the broker TerraCRG said the average transaction price in Greater Downtown Brooklyn in 2024 was $226/bsf, in Downtown Brooklyn $211/bsf, and in Gowanus $207/bsf.

The latter neighborhoods also had large development sites. Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park would have higher infrastructure costs, but they likely would be offset by “public resources.”

Public response

The meeting was “sold out,” in part because of a significant though not overwhelming presence of construction union workers in logo’d jackets, some of whom posed with the development team after the session.

Cirrus, which emerged last year and hasn’t yet built anything (though it’s been approved, with LCOR, for a project at the Flushing Airport site), is backed by the pension funds of the construction labor unions.

It has promised to build all union, saying that it’s not just the right thing to do, it adds quality and certainty. Union labor also delivers public and political support.

(Registration is open for a second, in-person workshop on Dec. 8, addressing multiple issues: streetscape and the public realm; environment and sustainability; local economic development; and community-serving retail and facilities. It will be held at Design Works High School, at the new Pacific Park campus at Dean Street and Sixth Ave.)

I saw a decent number of people I remember from Atlantic Yards public meetings more than a decade ago. It’s unclear how many residents of the 3,212 existing Atlantic Yards apartments attended, but some of them—especially in the buildings closest to the future construction sites—presumably would want to keep track.

While some people clapped at the developer’s presentation, others were frustrated by the set-up, with delays caused by the failure to provide a working public address system, the belated acquisition of a microphone (leading to a 6:39 pm start for a meeting slated to run from 6-8 pm), and small screens for the visual presentation that were out of view of many attendees.

“Perhaps most importantly, we need to press on accountability,” Prospect Heights resident Michael Rogers observed after the session, citing the ESD’s “oh never mind” posture toward the penalties, $2,000/month for the 876 affordable units not delivered by May 2025. Those were rolled over into a $12 million penalty that advocates call vastly inadequate. “ESD owes the community some meaningful commitments.”

When it comes to open space, nobody talked (yet) about governance. I’ve pointed to the phantom nature of the Pacific Park Conservancy and BrooklynSpeaks has suggested that the city Parks Department be put in charge.

Input and trade-offs

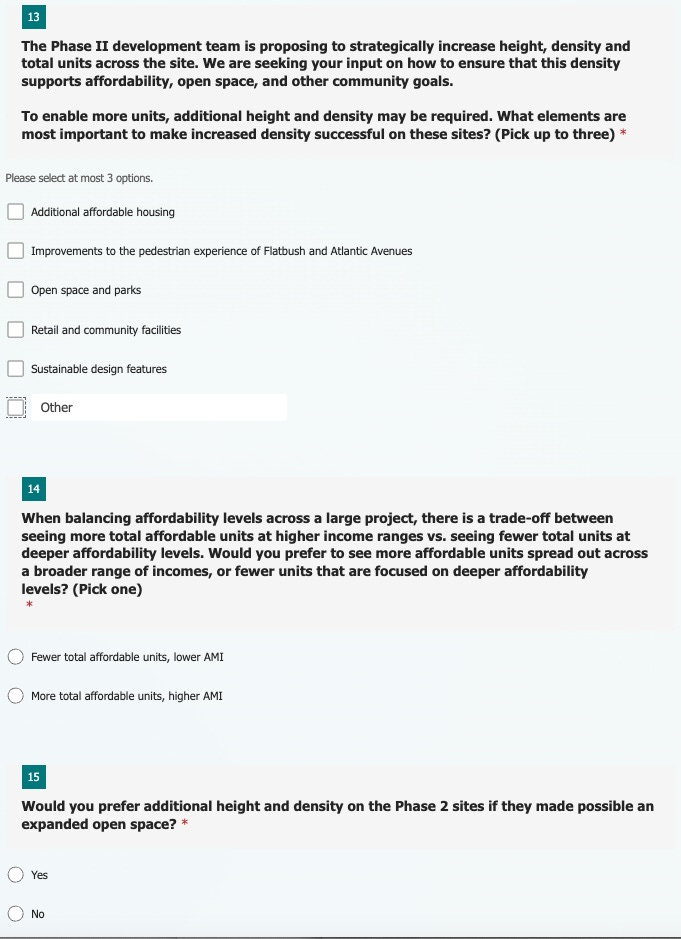

Here’s the handout given to attendees, seeking their input on what they like about Atlantic Yards and would want to change; how they feel about open space; and their preferences on affordable housing.

Attendees were told that, to enable more affordable units, “additional height may be required.” (Omitted: bulk.) They were asked to balance the priorities.

Similarly, they were asked to assess the trade-off between more below-market units at higher income levels and fewer at more deeply affordable levels. (Specifics, though, were scarce.)

Those questions are echoed in a new online survey regarding Atlantic Yards—see screenshot below.

There was no mention, as far as I could tell, of for-sale affordable units, an original priority of ACORN, nor of the importance of family-sized units.

There’s been no proposal yet of an alternate way to deliver public benefits without acceding to the developer’s blueprint—or of third-party experts to vet the validity of the plans. (There is no alternative?)

Here’s the handout given to facilitators at each of the tables. Those included representatives of ESD and the consulting firm Karp Strategies.

Videos of presentations

Below, ESD’s Joel Kolkmann introduces the session.

Below, Joseph McDonnell of Cirrus and Anthony Tortora of LCOR provide big-picture perspective on the project.

Below, Tortora and McDonnell offer key details.

Still “Atlantic Yards”

Despite the proposed provision of an additional acre of open space, thus bolstering what’s called “Pacific Park,” pretty much everyone used the project’s original name, Atlantic Yards, rather than Pacific Park Brooklyn, as Greenland renamed it in 2014.

I still could imagine another name change, escaping the past, and speculated it could be “Brooklyn Central,” especially if a housing surge increased the open space deficit.

In this case, the additional green space would be superior to the previous design, but I’m not sure an additional acre fully compensates for—and would meet the needs of—the expected increase in population.

At 2.14 people per apartment, an estimate used in previous project documents (which may be reduced if the project remains skewed to smaller units), that could mean a total population of 19,260 people. There’s likely demand. How well it all might fit remains to be seen.

Norman, thanks so much as always for your comprehensive reporting on this. We residents truly appreciate the updates!

The discrepancy betwen characterizing this as a 20% density increase when it's actually closer to 46% for railyard sites is significant. Using the arena square footage to minimze the perceived impact is misleading at best. The focus on 80-130% AMI affordability while avoiding deeper affordability commitments suggests this expansion prioritzes market viability over genuine community need. Your breakdown of the actual numbers and tradeoffs is essental reading for anyone trying to understand what's really being proposed here.