To Rescue Atlantic Yards, Developer Sought to Supersize Project

Greenland USA aimed to add nearly 2,700 apartments in six railyard towers, plus Site 5 opposite arena. Could expansion plan recur with successor?

This is the first of two parts. Most graphics by Ben Keel. Here’s Part 2, on the backstory. Updated Nov. 25, 2024.

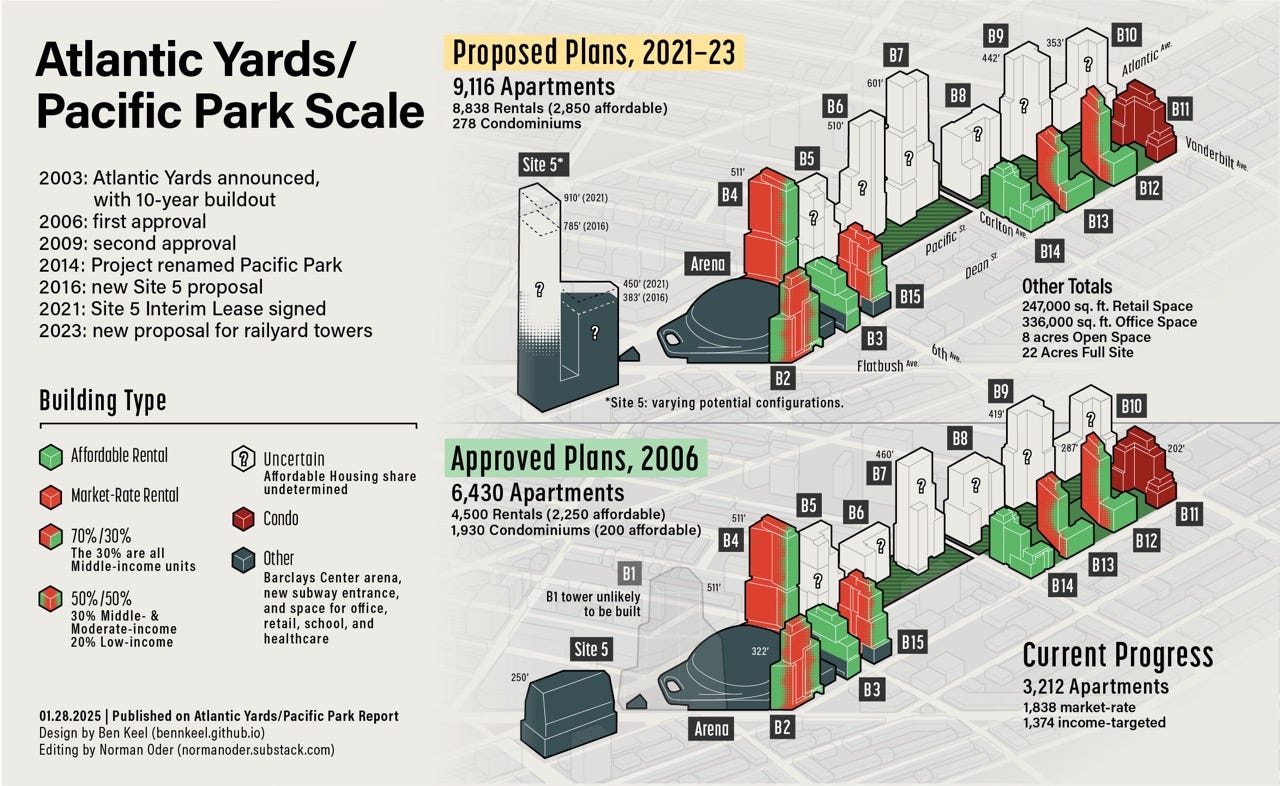

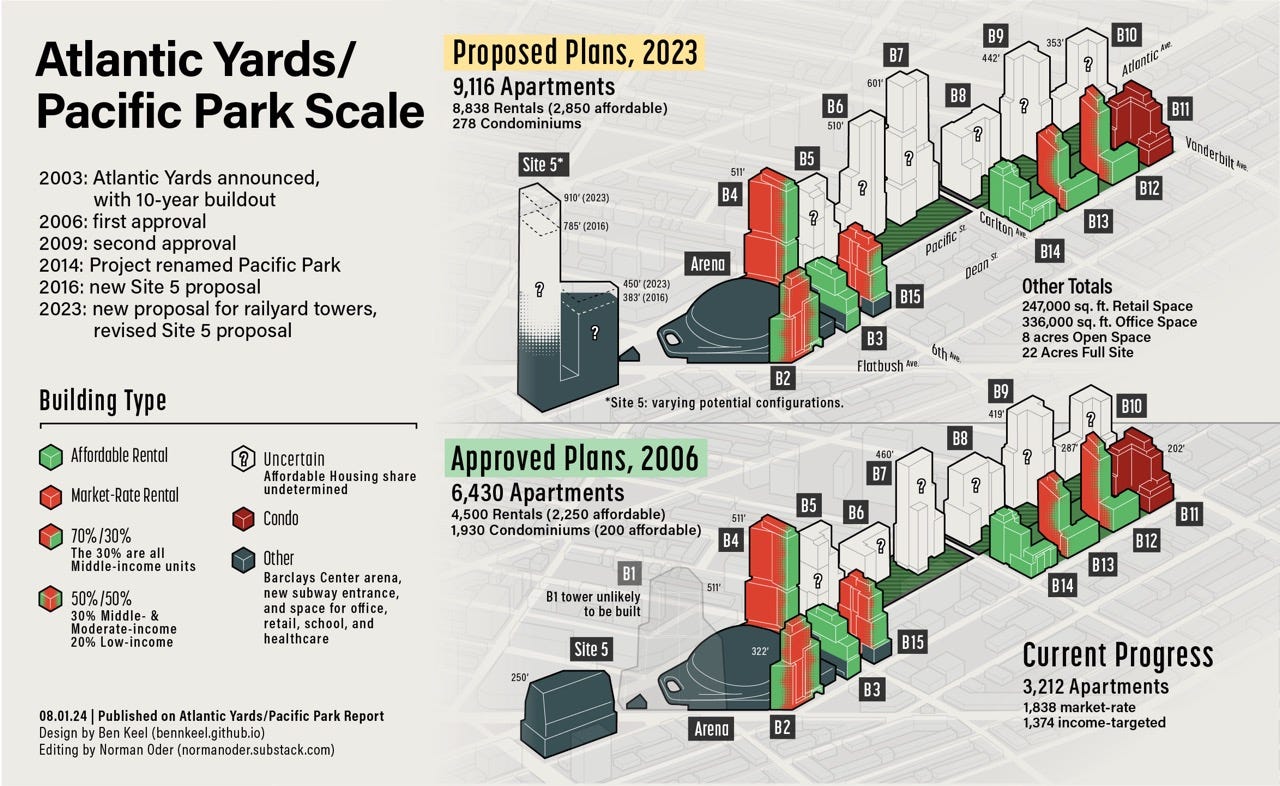

Recently released documents reveal the urgent attempts by Greenland USA, developer of Atlantic Yards (aka Pacific Park), to rescue the megaproject—after delays cascaded losses and a loan deadline loomed—by adding nearly 2,700 more apartments, according to my calculation.

That would’ve meant more than 9,100 total units, nearly 42% more than the approved 6,430. Given 3,212 built so far, that would mean about 5,900 more. The plan, which could recur, would deliver far more density than other large projects.

Greenland sought permission to add 1.8 million square feet—the volume of more than six Williamsburgh Savings Bank towers—to seven sites already approved for substantial buildings, boosting their value by hundreds of millions of dollars, while gaining extensions and other concessions from New York State authorities.

The dramatic increase in height and density would involve the project’s two remaining unbuilt zones. At six railyard parcels (B5-B10) marching east from the Barclays Center, Greenland sought 1 million square feet of new bulk, or 30% more, essentially gaining free “land.”

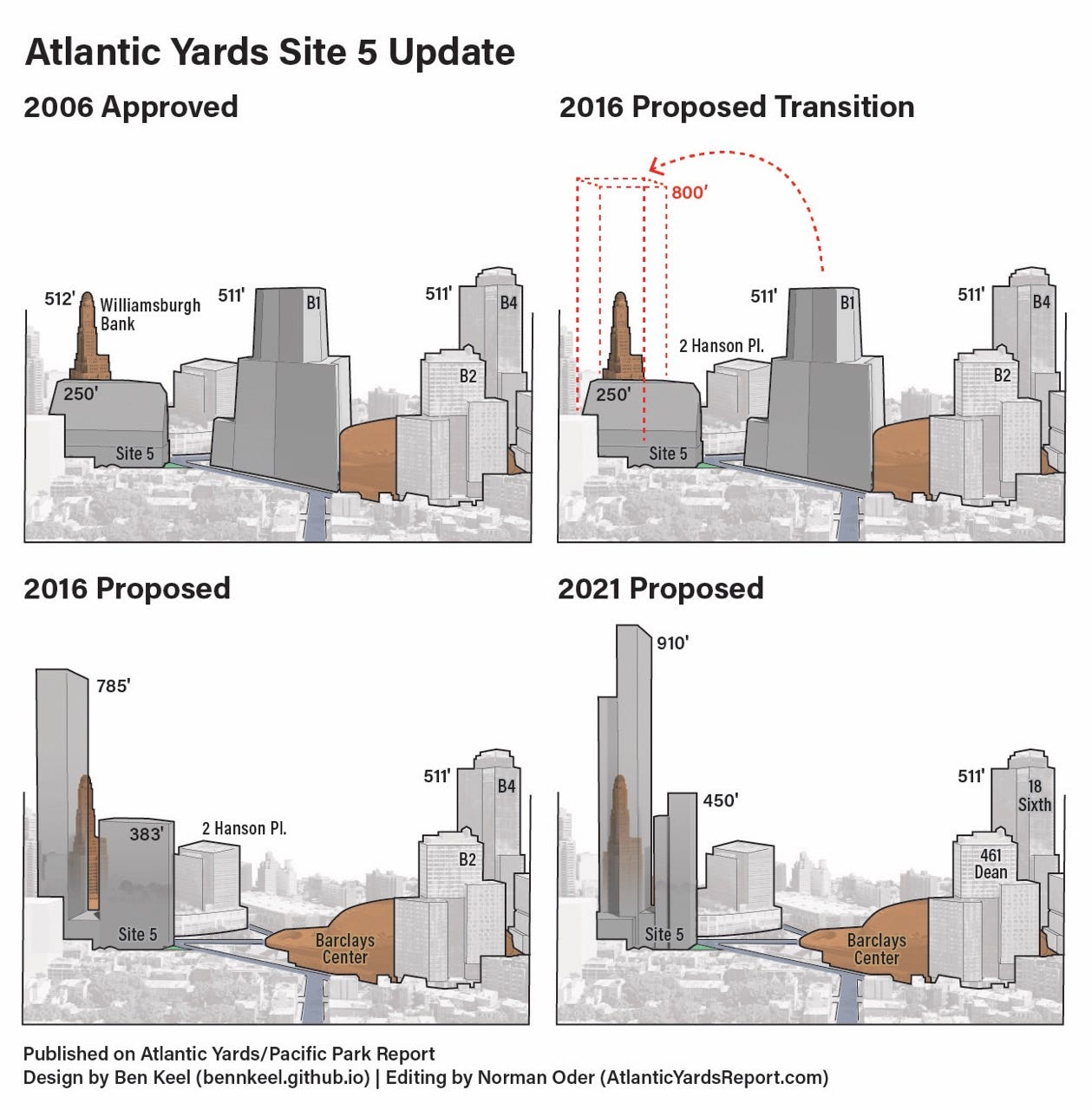

Changes at Site 5

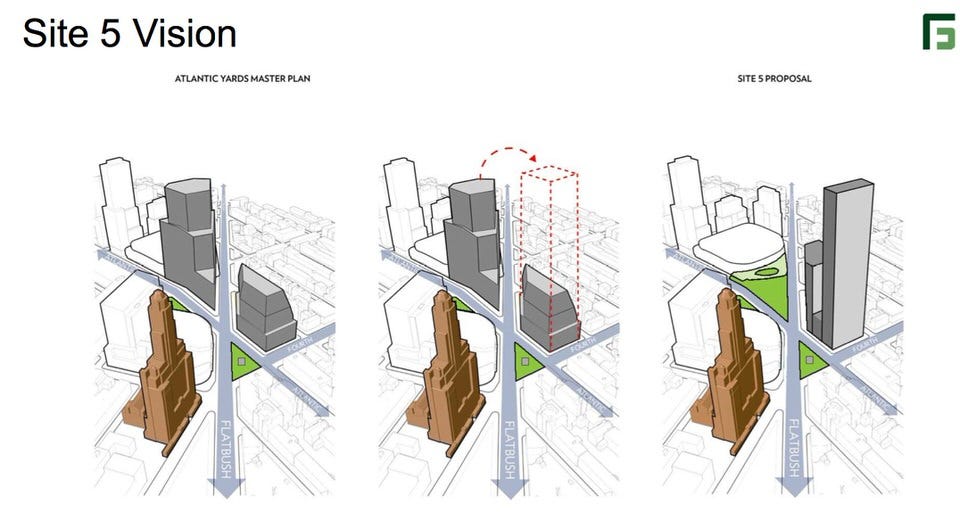

That would accompany another valuable process, first floated in 2015-16 and in October 2021 essentially approved: transferring 800,000 square feet, approved but not usable, mostly from the project’s unbuilt flagship tower (B1), once slated to loom over the arena at Flatbush and Atlantic avenues.

The air rights would go across Flatbush Avenue to Site 5, long home to the big-box stores P.C. Richard and the now-closed Modell’s.

That site was already approved for a 250-foot non-residential building with nearly 440,000 square feet. That two-tower Site 5 project, rising 910’ and with 1.242 million square feet, would have twice the density as that permitted in the 2004 rezoning of Downtown Brooklyn.

The plans were detailed in documents released by Empire State Development (ESD), the gubernatorially controlled state authority that oversees/shepherds the project, in response to my Freedom of Information Law request. (See these excerpts.)

The Interim Lease for Site 5 essentially committed ESD to support a larger project, which must be approved by the authority’s parent board.

Support, but no traction

ESD, the documents suggest, was generally supportive of Greenland’s full proposal, delivered Jan. 26, 2023, which built on changes negotiated more than a year earlier in the Site 5 Interim Lease.

Greenland also promised 600 more affordable apartments, albeit with an unspecified level of affordability and an extended timetable, That implied waiving penalties for the 876 more below-market units, of 2,250 required, due by May 2025.

However, ESD imposed conditions Greenland considered onerous, causing a stalemate, compounded by pandemic delays, rising interest rates, and uncertainty regarding the 421-a tax break. Greenland, unable to stave off what an executive called a “severe loss,” last November saw its six railyard parcels face a foreclosure auction, which has been postponed multiple times.

Will plan resurface?

While the 2023 proposals stalled, new versions may resurface soon, given recent disclosure that a successor developer—apparently, Related Companies—may emerge. After all, Related made its Hudson Yards plan viable by building bigger.

Beyond that, Greenland—with an expected partner/successor—has been invited to present an updated plan for Site 5, bounded by Atlantic, Flatbush, and Fourth avenues, and Pacific Street, to ESD. Surely that will build on the scale and elements established in Exhibit K of that Interim Lease.

New railyard plans likely would build on the 2023 proposal, increasing scale to boost revenue. Even with more public receptivity to density, that formula likely would provoke pushback, at least if such plans see sunlight rather than get presented as a fait accompli.

Also subject to debate would be the timing and affordability level of the below-market housing. Project proponents have long claimed that only the developer’s chosen scale could deliver needed affordability.

Site 5 shift means permanent plaza

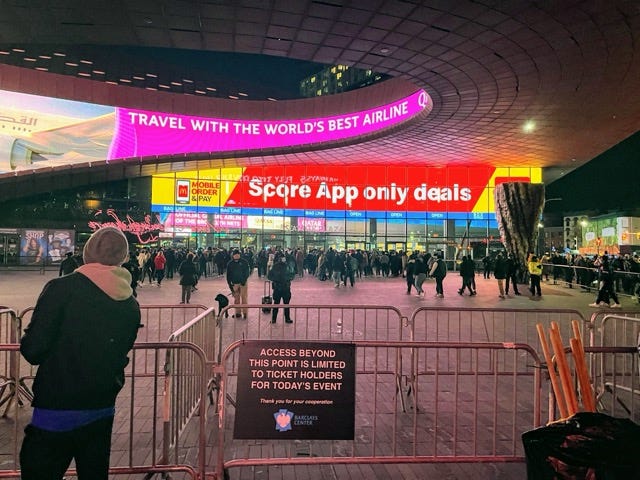

The two-tower project at Site 5 would contain about 100,000 square feet more than in Greenland’s 2016 proposal. That edifice could redefine a key crossroads, especially since Greenland sought permission for “dynamic LED signage,” another revenue generator.

(Might the arena operating company, owned by Brooklyn Nets owner Joe Tsai, want a piece of that, extending its reach beyond the Barclays Center’s oculus and LED wall?)

Meanwhile, the required Urban Room—the public atrium attached to the unbuilt flagship tower—would be eliminated, while the “Urban Experience” (aka the “temporary” plaza) would, as long expected, become permanent.

After all, that sponsored space, now Ticketmaster Plaza, is crucial to arena operations and revenue. I’ve argued that the public shouldn’t gift the plaza to Tsai’s BSE Global, with no compensation, Nor was BSE Global part of the 2023 negotiations.

Big plans, derailed

The documents did not spell out the total number of apartments, but noted that 25% of future rental units at the seven development sites would be affordable.

So, assuming no more condos, the plan would deliver, by my calculation, 9,116 total units, 2,686 more than approved in 2006 by ESD. The requested square footage might be worth more than $500 million, at least before encumbrances like below-market “affordable” housing.

Beyond tension with ESD, Greenland clashed with the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), whose cooperation was needed for the two-block platform over its Vanderbilt Yard, which would support the six towers. The railyard is used to store and service trains at Atlantic Terminal, the Long Island Rail Road’s Brooklyn terminus. Each of two platform phases could take three years.

The impasse ultimately led Zhang Yuliang, chairman of Greenland USA’s Shanghai-based parent company, Greenland Holding Group, to lament, in an email to a key gubernatorial aide last August, a “grim situation” that couldn’t resolve the developer’s “severe loss.”

Foreclosure blues

None of this roiling backstory was known when, last November, a foreclosure auction surfaced for those six railyard development sites, which encompass—before the requested expansion—nearly 3.5 million square feet of approved bulk.

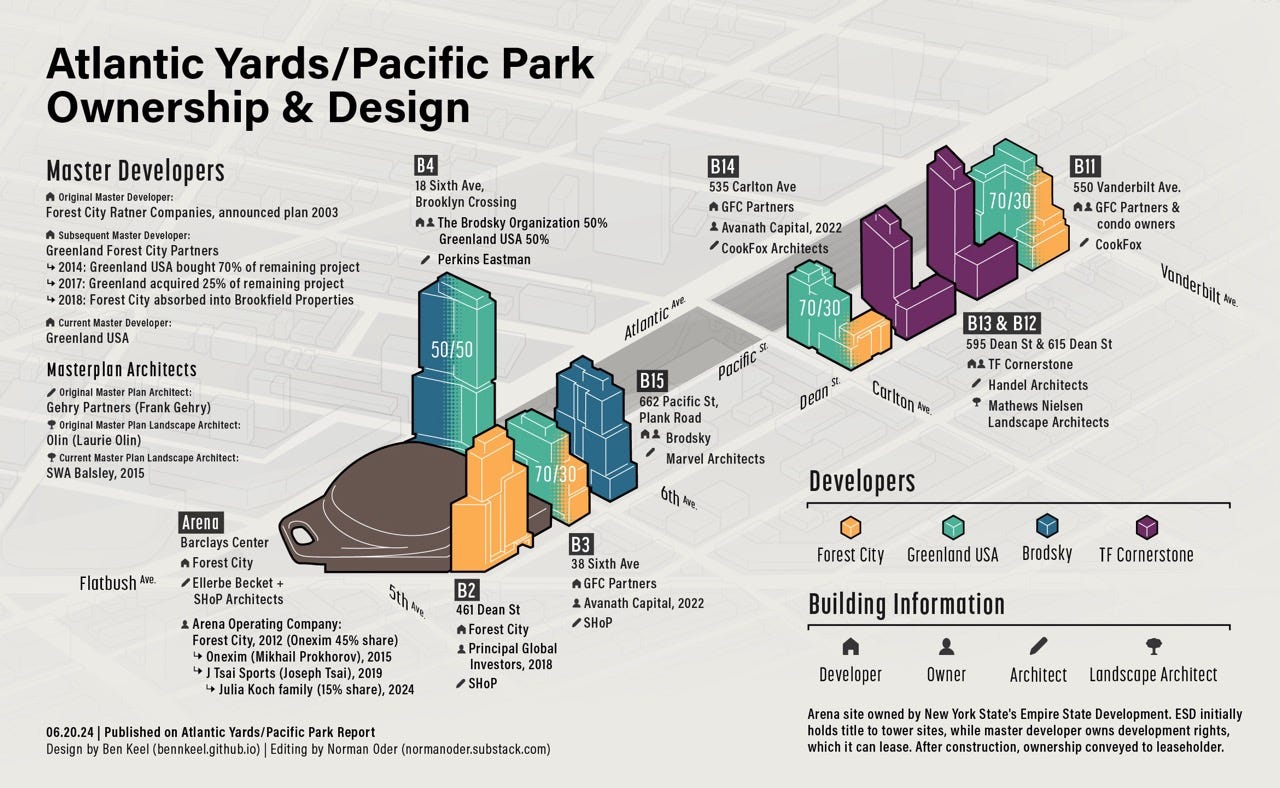

More than 20 years after Atlantic Yards was announced by established Brooklyn developer Forest City Ratner, eight of 16 approved towers, plus the arena, have been completed, but the yet-to-be-covered railyard signals project stasis, as well as a failure to cure purported “blight.”

In 2014, Greenland took over 70% of the remaining project, excepting the arena and one under-construction tower. It built three towers, plus infrastructure, in a joint venture with Forest City.

By 2018, Forest City exited the project almost completely, its 30% share cut to 5%. Forest City was later absorbed into Brookfield. Its share has shrunk even more.

Four more towers rose after Greenland leased three tower sites to two developers, and at a fourth site built a tower jointly with one of those firms. All were built on terra firma, with no platform required.

Mounting costs

The slow buildout limited cash flow, even as moving the railyard functions, along with starting foundations for the platform, compounded costs.

Greenland Forest City in 2014 raised $349 million from foreign nationals, mainly from China, who each invest $500,000 under EB-5, a federal program that grants green cards in exchange for purportedly job-creating investments. They accept no or low interest, but expect their money back in seven years or so.

They were only partly repaid. Now Greenland owes some $286 million to those investors, mainly from China, with the debt controlled by an affiliate of the middleman U.S. Immigration Fund, the “regional center” that recruited the investors, plus the investor Fortress. The Greenland subsidiaries with rights to the six tower sites served as collateral.

That foreclosure auction has been postponed multiple times, likely because any bidder must negotiate with both ESD and MTA to unlock the sites’ development potential. A negotiation with Related has apparently been ongoing.

One looming deadline: ESD is supposed to impose $2,000/month fines for each of the remaining 876 affordable housing units not built by May 2025, a deadline set after a June 2014 settlement with the BrooklynSpeaks coalition, which had threatened a lawsuit based on fair-housing grounds.

Greenland last year sought to extend project obligations, so far without success, according to the documents. Any successor surely would seek an extension, as well.

Feint at progress

It’s been a rough ride. Two years ago, after a pandemic slowdown, Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park seemed poised to progress. In June 2022, Greenland said it would soon start work on the first block of the two-block platform, pending permits. A month later, they were still optimistic.

But work didn’t start. The documents show escalating tension over what the developer considered roadblocks from public agencies. Beyond the extended deadlines and additional bulk, Greenland even sought more direct subsidies, apparently to complete the platform.

That impasse, in turn, torpedoed Greenland’s plan to sell railyard development rights to another, unnamed company—Related?—and recoup some of its investment, while, presumably, paying off the EB-5 investors. Then, as interest rates rose and the 421-a tax break expired, the relationship between Greenland and state officials got increasingly frosty. (See Part 2 for more details.)

The rescue plan

The rescue plan would have required a public engagement process and public hearings before a new approval by the ESD and an updated Modified General Project Plan.

The documents suggest that, to become financially viable, Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park needed not merely a gubernatorial “nudge”—as the New York Daily News recently editorialized—but more extensive concessions. (Of course, developers often overreach, to enable seeming concessions.)

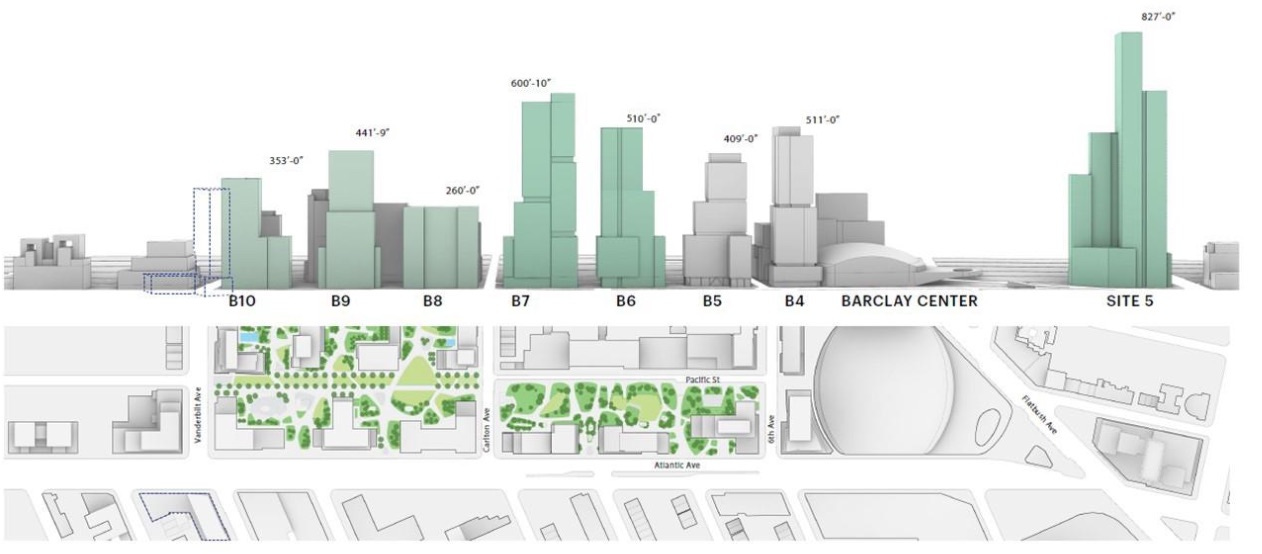

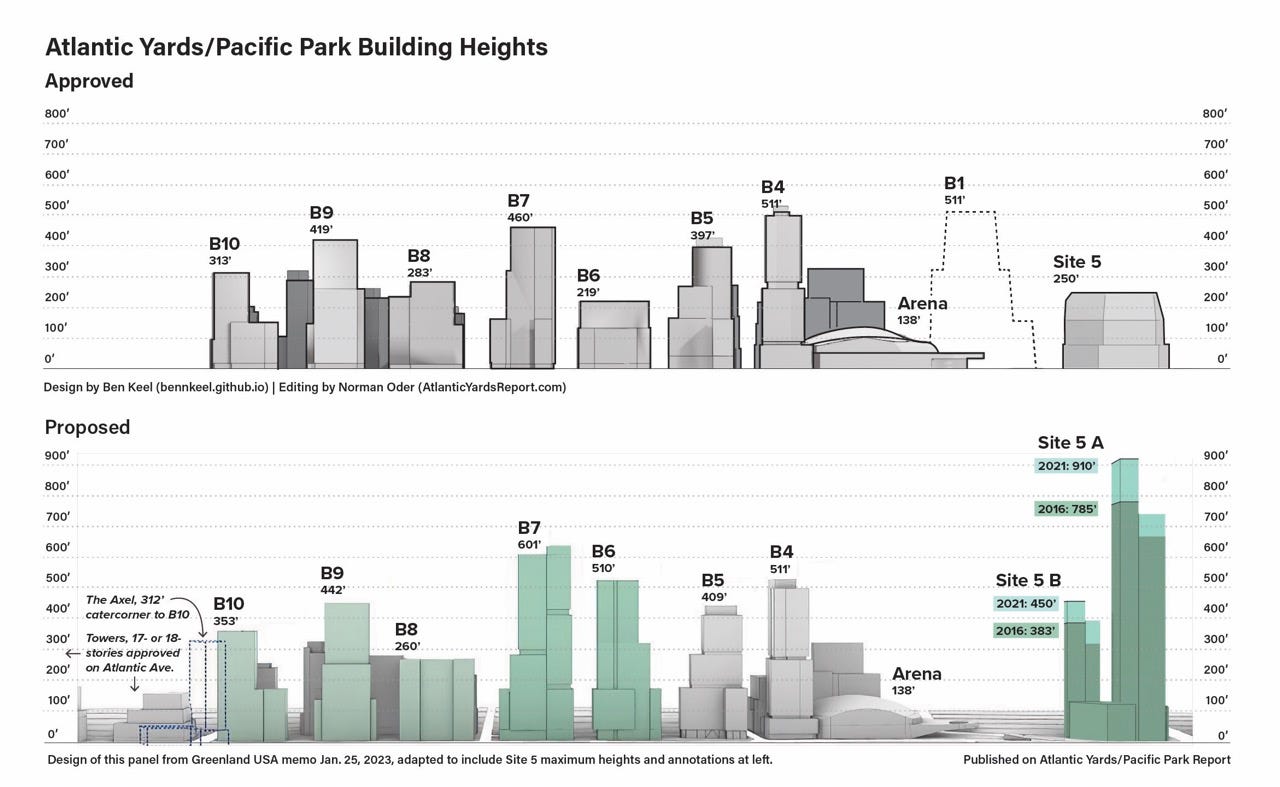

While Greenland proposed 1 million more buildable square feet (bsf) at the railyard sites, its tower-by-tower list indicated more modest increases, totaling about 500,000 more bsf. Note: the link above does not propose changes for B5, though the Greenland graphic up top suggests a height of 409’, not 397’.

While no change in the B5 tower, already designed, was contemplated, the developer, in its Jan. 26, 2023 proposal, sought to create taller, bulkier buildings to the east, with two buildings, B6 and B7, matching and exceeding the height of the tallest current building, B4, which is 511 feet.

Given that Greenland underestimated bulk, it’s likely a revision would produce bigger buildings. According to the chart above, B6 and B7 would not be bulkier than B4 (18 Sixth Ave., aka Brooklyn Crossing), which contains about 824,000 square feet.

However, Greenland’s graphic above leaves the possibility they might be larger.

Jousting with the state

Greenland USA President Gang Hu, after meeting with gubernatorial aide Kathryn Garcia and other state officials, followed up in a cordial March 20, 2023 email, implying a consensus on supersizing the project.

“We welcome your statements regarding ESD's commitment to this project, especially regarding ESD's commitment to working with the developer to right-size the permitted development to make the project feasible,” Hu wrote. He used “right-size” as a euphemism not for a reduction, as is common, but for an expansion.

“We welcome… ESD's commitment to working with the developer to right-size the permitted development to make the project feasible.”—Greenland USA President Gang Hu

However, the state authority pushed back. Writing April 10, 2023, Arden Sokolow, Executive VP, Real Estate, noted that, because the Site 5 changes “will involve public hearings and may face opposition,” ESD sought “better visibility into timing of the Platform and your ability to meet” affordable housing obligations.

In other words, they apparently heeded warnings, voiced by the BrooklynSpeaks coalition, that Greenland not be allowed to expand Site 5, which it might then sell, without committing to the railyard parcels and affordable housing.

The recent movement on Site 5—in which the Chairman of the advisory Atlantic Yards Community Development Corporation, in a curiously orchestrated motion, in June requested that ESD ask Greenland for a proposal—may have been spurred by progress with a new developer for the railyard parcels.

The MTA’s requirements also delayed the platform, Hu wrote May 26, 2023 to Gov. Kathy Hochul. That forced Greenland to miss the window for the expiring 421-a tax break.

That, he revealed, “led to the termination of a signed purchase and sale agreement for a future Platform vertical project”—with an unnamed developer, though Related’s a plausible bet—"and caused substantial financial losses to Greenland.”

Indeed, Greenland this year disclosed a $390 million impairment, or loss in value, from its investment in Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park.

Valuable new bulk

The documents don’t show whether state officials tried to value the additional 1 million square feet in railyard development rights, but a rough estimate suggests $200 million to $300 million or more. Terra CRG’s 2023 investment report valued larger sites in nearby Downtown Brooklyn at $307 per buildable square foot (bsf). That was before the new 485-x tax break.

With that tax break, which triggers somewhat deeper affordable housing than its predecessor 421-a, another real estate broker told The Real Deal of sites trading for about $200 bsf, less than the previous $200-$250 bsf.

Such new revenue could help fund the platform, the first phase of which would cost more than $150 million and likely would cost over $300 million.

From one perspective, those railyard sites may offer a premium, given the location’s proximity to transit and established neighborhoods. However, that’s counterbalanced by infrastructure costs and affordable housing obligations.

So an unbiased analysis would be helpful. In 2018, Jaime Stein, a member of the Atlantic Yards Community Development Corporation (AY CDC), proposed that the advisory board hire its own planning, design, and construction consultants to review the expected Site 5 proposal.

Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park’s tough to value, since the existing 3.49 million square feet in development rights, at least at the time of the negotiations, likely weren’t worth $200–$240/bsf (and $700–$838 million), given the cost of the platform, the affordability requirements, the uncertainty of financing, and the expired tax break. Otherwise, Greenland would’ve paid the debt.

Greenland, through June 2023, had paid the MTA $96 million for development rights over the railyard, perhaps enough to purchase the rights to build the first three towers. It didn’t pay the June 2024 installment on time, perhaps because a new developer would assume such payments.

An additional $77 million due to the MTA, in annual $11 million increments, by June 1, 2030, would give a developer the right to build the final three towers. It’s unclear whether Greenland can realize any value for its past investment, given the foreclosure.

It’s also unclear why any new developer should be given additional development rights, the equivalent of more land, without some stake for the public and/or further payment to the MTA. Presumably the proposed new affordable units will be framed as reciprocity.

The Site 5 boost

Greenland’s revised Site 5 plan posits another value boost. While ESD in 2006 approved a building at 250 feet and 439,050 square feet, the developer in 2016 proposed a two-tower project containing 1,142,052 square feet, with the towers rising, respectively, as tall as 785 feet and 383 feet, thanks to bulk transferred from the unbuilt B1 tower.

See graphic below, looking southeast from a hovercraft perspective: it focuses on the Williamsburgh Savings Bank (aka One Hanson) in the foreground, with B1 and Site 5 in gray and B4 top left.

In October 2021, as part of a new interim lease for Site 5 (see Exhibit K), Greenland proposed adding 100,000 more square feet, enabling a 910-foot tower and other changes.

None were disclosed to the public nor the Atlantic Yards Community Development Corporation, which is supposed to be “[r]eviewing proposed changes to Project plan and agreements, and advising ESD board accordingly in advance of votes.” (I asked the state authority for comment yesterday, but didn’t hear back.)

That would surpass the tallest building approved nearby, the pending 840-foot tower in the Alloy Block (aka 80 Flatbush) and be the borough’s second-tallest, after the new, 1,066-foot supertall, The Brooklyn Tower, several blocks up Flatbush Avenue. The second Site 5 tower could rise 450 feet.

Yes, the above rendering—looking north from Park Slope toward Site 5 from a perspective several hundred feet up—is just one alternative, and more are needed.

Would Site 5 block the bank and its signature clock, currently shown via transparency? We can’t be sure of a final design, but I wouldn’t bet against a partial block. After all, the clock has already been blocked by the B2 tower, 461 Dean Street, for those looking northwest.

More Site 5 changes

Along with housing, Site 5 could include a hotel with up to 550 rooms, far larger than the 180-room hotel previously approved for B1, according to Exhibit K.

Would that rival the New York Marriott at the Brooklyn Bridge, which has 638 rooms and 28 suites or, if Related’s Time Warner Center and Hudson Yards serve as templates, more upscale brands like Mandarin Oriental or Equinox? Surely there’d be suites for visiting arena performers and teams.

The Site 5 plan also would include an unspecified amount of underground space for retail, substituting for 240 spaces of costly below-ground parking, another financial boost.

Greenland requested that the retail space—which a developer’s rep once likened to the Time Warner Center, before that complex was renamed Deutsche Bank Center—not count against the building’s approved square footage.

Putting aside the retail space, the overall Site 5 square footage might be worth more than $300 million. (That includes the previously approved space, plus the bulk transfer.) Then again, in one 2021 transaction, Greenland perhaps unrealistically valued that site at some $606 million.

As proposed, Site 5 would be unusually large, with a proposed Floor Area Ratio, or FAR, of 25.5.1 (FAR measures bulk as a multiple of the underlying lot.) That’s more than double the maximum FAR in the Downtown Brooklyn rezoning, which was 12. The Alloy Block gained an FAR of 15.75.

Design intent

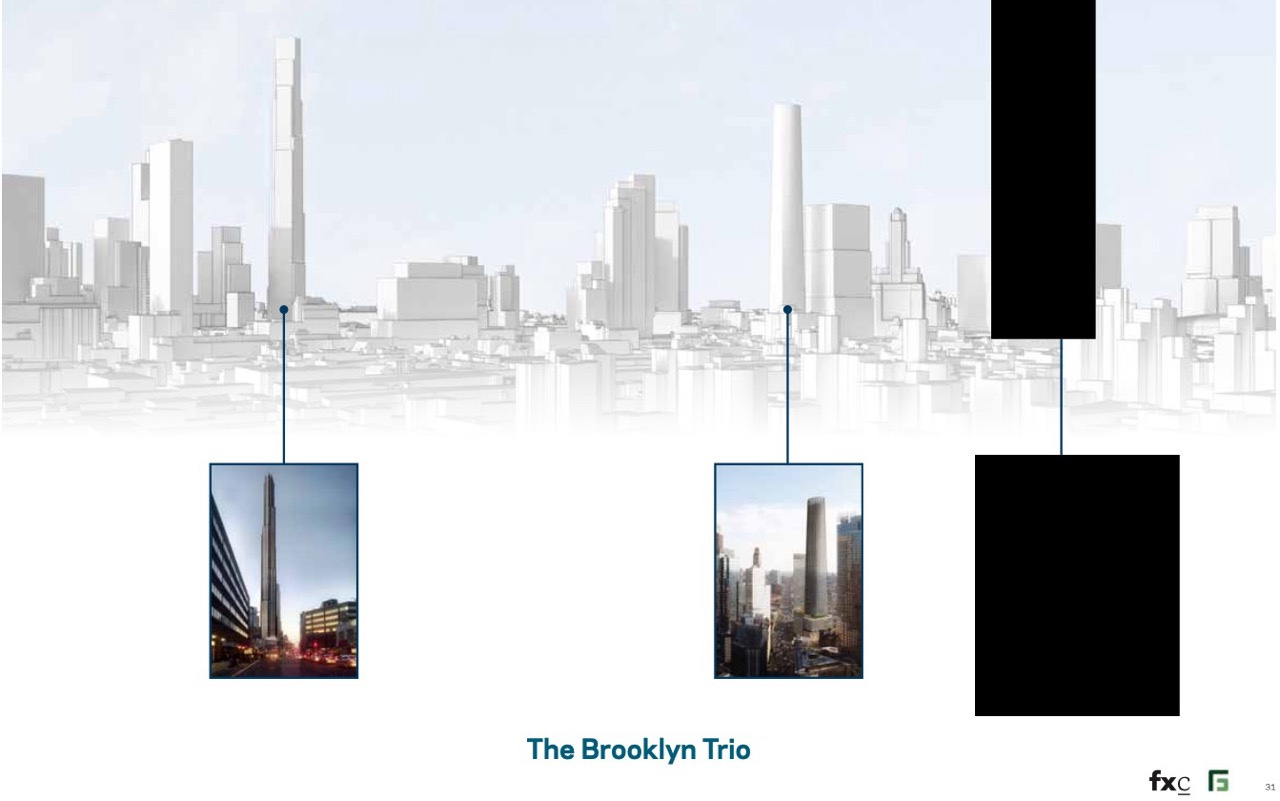

Exhibit K of the interim lease referred to a “design intent” prepared by FX Collaborative it. Here’s the full presentation and my article on it. Two excerpts are below.

According to the presentation made to state officials in November 2018, the 910-foot tower at Site 5, would be part of “The Brooklyn Trio,” including the borough’s sole supertall, The Brooklyn Tower, and the planned 840-foot tower at The Alloy Block, formerly known as 80 Flatbush.

Whether the three towers, assuming they’re all built, comprise a trio surely depends on the perspective. Below is the list of modifications requested, which was manifested in Exhibit K.

More, but slower, affordable units

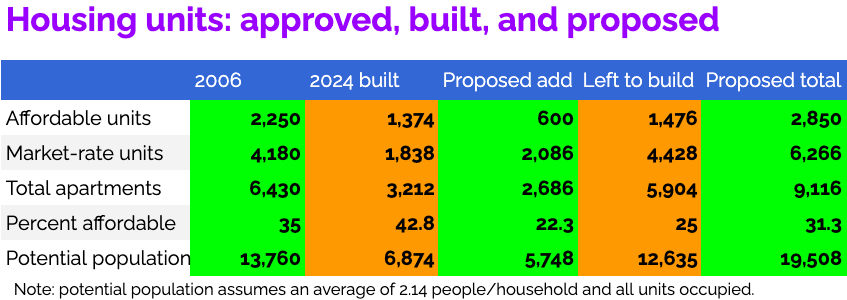

Greenland, seeking support for its revised plan, proposed adding 600 income-targeted apartments to the 2,250-unit obligation, while extending the May 2025 affordable housing deadline considerably and, presumably, waiving those $2,000/month fines.

As of January 2023, the developer proposed to “substantially complete approximately 2,000” affordable units by 2029. Given 1,374 constructed so far, that would’ve meant 626 more apartments over six years, not the 876 required to meet the May 2025 obligation. (If a similar proposal recurs, that deadline surely would be nudged back.)

The developer also would commit to “delivering approximately 2,850 Project Site Affordable Housing Units by the Project Outside Date.” That would’ve meant 850 more affordable units within six years after 2029.

That Outside Date, set as May 12, 2035, allows for a 25-year buildout, but Greenland sought an extension. A new plan surely would include a new extension request.

The documents don’t specify the affordability level, which would depend on both available subsidy programs and any special negotiations. But units, as of the proposal, were to stay affordable for a 35-year term. Today, the new 485-x tax break, which surely would shape a revised plan, requires permanent affordability.

More total apartments

The documents don’t outline the project’s unit total. However, if 25% of future rental apartments are affordable, the projected 1,476 below-market units left to build would be among 5,904 future rental units, including 4,428 market-rate ones.

As noted, that would mean nearly 42% more total project apartments, 9,116 from 6,430, thanks to both the additional bulk and a swap from approved office space.

Extrapolating from the formula provided, 2,086 market-rate units would be added to the 4,180 approved, while 600 affordable ones would augment the 2,250 approved.

So, while Atlantic Yards was approved with 35% affordability, the proposal implies 31.3% affordability. (Originally, half the apartments were supposed to be affordable, but that was later said to apply only to rental units.)

At 2.14 people per apartment, an estimate used in previous project documents (which may be reduced if the project remains skewed to smaller units), that could mean a total population of 19,508, assuming all units were occupied.

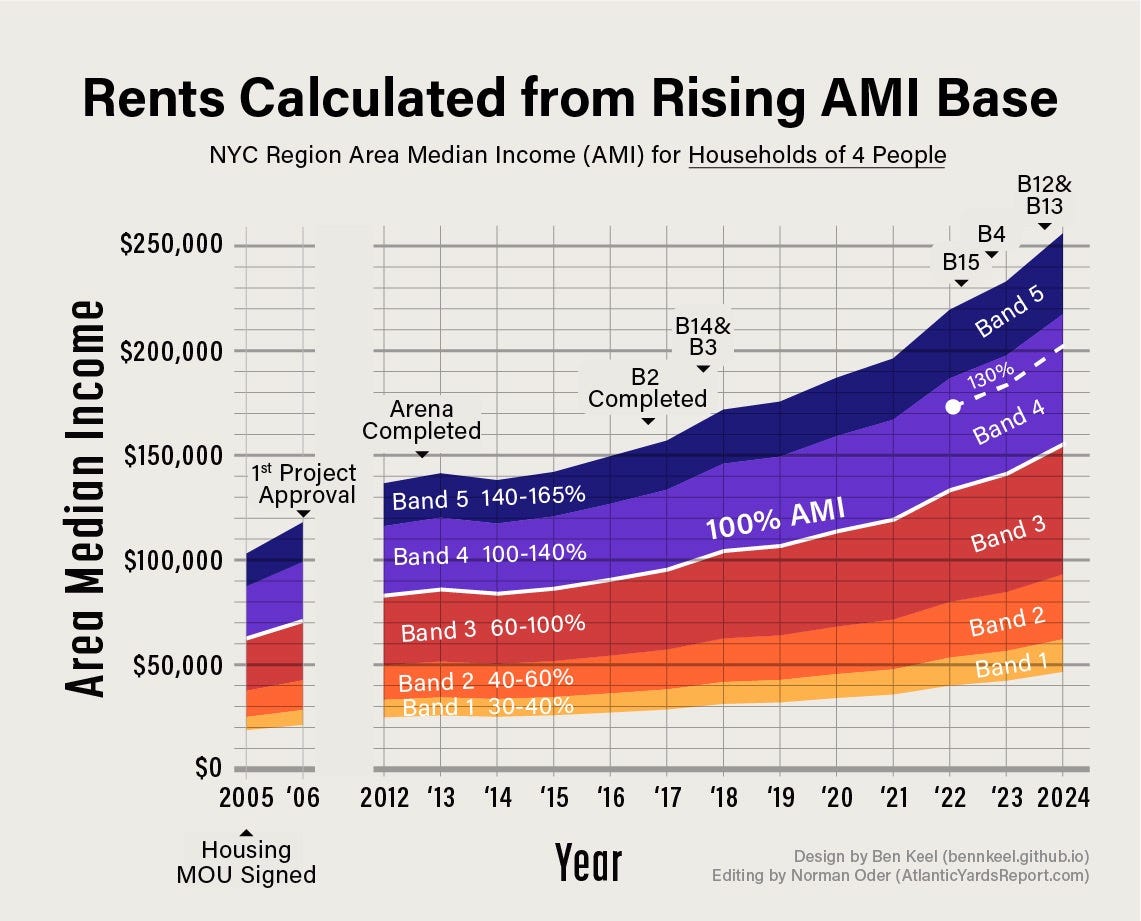

Affordability not predictable

The changes would face a state public approval process, controlled by the governor, limiting local legislators’ input. That wouldn’t necessarily address key issues. The new 485-x tax break does mandate 25% affordability at a blended average of 60% of Area Median Income.

The civic value of below-market housing depends not just on the number of units, but the timing of delivery and the level of affordability, which relies on both off-the-shelf tax breaks and discretionary subsidies.

The affordability has varied greatly in Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park. An even mix of low-income and middle-income units was promised in a non-binding 2005 agreement with the advocacy group ACORN and incorporated in the project’s overhyped Community Benefits Agreement. That didn’t happen.

For example, the only “affordable” apartments in the last four buildings have been middle-income ones, at 130% of Area Median Income, or AMI. That was enabled by the 421-a tax break.

See Keel’s graphic, below, to see how built units have skewed more expensive.

Delay hampers affordability. AMI, the base for affordability calculation, has more than doubled since the project was approved. That raises the baseline income, with a four-person “low-income” household, at 60% AMI, today earning up to $93,180.

Tweaking design for more open space

The increased height, as proposed, would allow the footprints of two railyard towers, B6 and B7, to shrink somewhat, from modified L shapes to become more rectangular, thus permitting more publicly accessible, privately managed open space.

A similar strategy was used when new owner Two Trees revised the Domino Sugar project in Williamsburg.

That open space would augment the eight acres already promised, supplying a greater buffer zone between the towers and Pacific Street. The total increase was not specified.

More open space from Pacific Street?

Greenland sought to claim more open space. The developer suggested that ESD work with the New York City Department of Transportation “to explore using additional portions of Pacific Street, between Sixth and Carlton avenues, as Open Space.”

That’s outside towers B5-B7. Pacific Street, between Carlton and Vanderbilt avenues to the east bordering the B8-B10 sites, has already been demapped. After serving as construction staging, it would supply key open space once B8-B10 were completed.

Though that proposal was not fleshed out, expanding what’s been dubbed “Pacific Park,” it implies adding public property without compensation.

The rationale seems clear: even with slightly more open space bordering B6 and B7, the project’s total open space, on a per capita basis, surely would decrease, due to the population increase.

If a portion of Pacific Street were added, the open space ratio might still decrease. That would cast further irony on Greenland’s 2014 decision to change “Atlantic Yards” to “Pacific Park.”

The lot at Site 5, as noted in a presentation prepared by developer Greenland Forest City Partners in January 2016, is 48,655 square feet. With the proposal of 1,242,000 square feet, that exceeds an FAR of 25.5.