Penn Case Study: Atlantic Yards Lacked Edge Hudson Yards Had

Easier transaction, more density, transport subsidy. But researchers ignored Hudson Yards' huge EB-5 fundraising and impact of Downtown Brooklyn rezoning. Sloppy, too.

Why did Atlantic Yards falter? Are there any useful contrasts with Hudson Yards in Manhattan?

Well, both journalists at The Real Deal and I have tried to answer the first question, but not necessarily the second one.

In a 2020 case study of Atlantic Yards, two academics from the Penn Institute for Urban Research took on both questions, suggesting that, despite superficial similarities--size, need for platform, start year--the megaprojects differed significantly.

Authors Eugenie Birch and Amanda Lloyd prepared the study well before Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park faltered again, with six development sites over the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s (MTA) Vanderbilt Yard going into foreclosure, given master developer Greenland USA’s inability to pay back EB-5 loans.

Since that late 2023 news, Hudson Yards developer Related Companies has emerged as part of an expected joint venture to develop those Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park sites. So Related is slated to become, essentially, the new master developer.

Key contrasts

The study was prepared for a joint research initiative between the Korea Housing and Urban Guarantee Corporation (HUG) and the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

The authors note a key contrast with land assembly. While Hudson Yards had one transaction, with the MTA, and is nearly all a railyard, Atlantic Yards required many transactions and is mostly not a railyard. The latter acquisition process was not just more complex but also vulnerable to lawsuits.

Another contrast involves funding of transit improvements: the Hudson Yards developer got full public support—though it’s complicated—for a subway extension, while the Atlantic Yards developer had to fund a revamped MTA railyard in Brooklyn to store and service Long Island Rail Road trains.

Of course, the cost of the latter infrastructure was supposedly factored into the inside-track transaction between original developer Forest City Ratner and the MTA for development rights to those six railyard towers.

(Note: the study reports that the “cost of the railyard air rights doubled.” Not quite. Forest City initially bid $50 million, while later entrant Extell bid $150 million. New York State chose to negotiate solely with Forest City, which upped its cash bid to $100 million, claiming the rest of the package was worth more than Extell’s overall bid.)

Another contrast involves density: at Hudson Yards, Related was allowed to build far larger than at Atlantic Yards, which means more office, retail, and residential space available for rent.

Last year, current Atlantic Yards master developer Greenland USA proposed, unsuccessfully, to rescue the project by seeking more density—essentially, free “land.” The next developer likely would make similar requests.

Glaring omissions

So the Penn researchers got some big-picture things right, but missed two key issues. Hudson Yards developers were able to raise—but not repay!—an extraordinary amount of low-cost capital via EB-5 investor visas, far exceeding what the Atlantic Yards developers were able to raise.

Also, while Hudson Yards is essentially an enclave, able to offer a premium product in its own market, Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park residential towers faced devastating competition from new apartments built in nearby Downtown Brooklyn.

Consequently, Forest City lost far more in its initial sale to Greenland than the $42 million claimed in the study.

Taking it seriously

Upon first reading the study, I dismissed it, since it’s riddled with errors small and large. For example, it calls the venue “Barclay’s Center” (rather than Barclays), a key state entity the “Metropolitan Transit Authority” (rather than Transportation) and refers to the project’s guiding document as the General Plan Agreement, rather than the General Project Plan or Modified General Project Plan.

More significantly, it claims the four housing towers launched after 2020 would fulfill the project’s affordable housing requirements by 2025. Not so. As of January 2019, I reported that the towers would be at least 25% affordable, with the implication that several more buildings would be necessary.

While they turned out to be 30% affordable, that left 876 units to go, with a May 2025 deadline that won’t be met.

However, because the study is being used in university classes, as I’ve learned, it demands a careful read, both with appreciation for some big-picture contributions noted above and with alarm at some major omissions and glaring errors. (It’s also a non-cited source for this myopic NYU Schack School of Real Estate student op-ed.)

So this is a long piece, but it’s a necessary corrective, though hardly a final word.

Many flaws

The paper mostly lacks sourcing and is hampered by significant sloppiness. It refers 20 times to the nonexistent “General Plan Agreement,” and only once to the Modified General Project Plan, or MGPP. (Was something lost in translation?)

It claims that, in 2006, a Forest City subsidiary called “Forest City Development Corporation (FCDC) and the State of New York signed the public-private partnership, called the General Plan Agreement.”

However, there was no subsidiary with that name. Forest City’s Atlantic Yards Development Corporation, among other entities, signed a Development Agreement with the state on March 4, 2010.

The caption on the image below, "Original Frank Gehry Masterplan," is wrong on two counts. The masterplan involves a 22-acre site with 16 towers, plus an arena. (See, for example, the Design Guidelines.) This shows just the arena block, with four towers.

Moreover, it's not Gehry's original arena block--check here and here for images--but rather a May 2008 update, four and a half years after the project was announced in December 2003.

Was Atlantic Yards manageable?

The authors write:

The question of why the Pacific Park project has had so many setbacks and delays offers lessons in the challenges of megaprojects and risks than can only be partially mitigated by public-private partnerships. In the original proposal, the complexity of the Atlantic Yards project looked manageable; In 2003 the developer was highly experienced and would be his own anchor tenant, the growth of the Brooklyn residential market was promising, and the State of New York was strongly motivated to help fill a physical hole in the center in what was otherwise solid residential neighborhoods. How did an estimated 2016 completion date extend nearly 20 years to 2035?

Maybe it looked manageable under a best-case scenario. Remember, Deputy Mayor Dan Doctoroff considered the proposal, when he first learned of it, to be "a crazy risk," as he wrote in his 2017 memoir.

What about Forest City Enterprises CEO Chuck Ratner, who in March 2007 acknowledged at an industry conference that "we are terrible… on these big multi-use, public-private urban developments, to be able to predict when it will go from idea to reality.” So, Forest City expected delays; it just wasn’t able to wait them out this time.

Contrast the authors’ surprise at the extended completion date for Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park with their acceptance of 2024 as a completion date for Hudson Yards. Yes, it was before the pandemic upended Hudson Yards, but shouldn’t they know that big real estate projects, with many moving parts, often get delayed?

Discussing Atlantic Yards at a 2012 panel before the arena opened, Marilyn Taylor, then Dean of the University of Pennsylvania's School of Design, offered some sage advice: “Be honest about phasing: nothing ever gets built at once.”

Today, 28-acre Hudson Yards is about half complete, with the 13-acre Western Rail Yards (WRY) site uncovered. The best-case scenario for completion is 2030, at least if Related wins the right to build a casino, which is hardly certain.

Original timing

Forest City, claiming a ten-year buildout, initially said Atlantic Yards would be completed by 2013, a date extended after each delayed milestone, including the project’s approval in 2006 and revision in 2009.

That calculation was bogus, developer Bruce Ratner later admitted. "It was never supposed to be the time we were supposed to build them in," he told WNYC's Matthew Schuerman in 2010, under the headline, "Ratner Abandons 10-Year Timeline for Atlantic Yards."

The extension to 2035 was provided by Empire State Development, during the master closing in December 2009. “There is a ten-year timetable,” an ESD lawyer had said at a July 2009 public meeting. “However, we need the capital markets, we need the residential markets, to cooperate, so there is the possibility that the project will be delayed."

At an ESD meeting in December 2010, another lawyer explained, "The agreements require the developer… to use commercially reasonable efforts to achieve a completion date of 2019 [and] set a framework, where the market demand for the project's buildings can be expected to bring the project to completion as soon as it is commercially reasonable… The documents separately set forth the outside completion date of 2035."

New timing

At a public hearing in May 2014, a Forest City executive Jane Marshall blamed ESD for imposing “outside dates by which, if we did not finish the project, we would be in default… This 25-year outside date was never viewed by Forest City as a proposed construction schedule but as a date by which we failed. We have always intended to complete the project much, much sooner than that, and we will.” (They didn’t.)

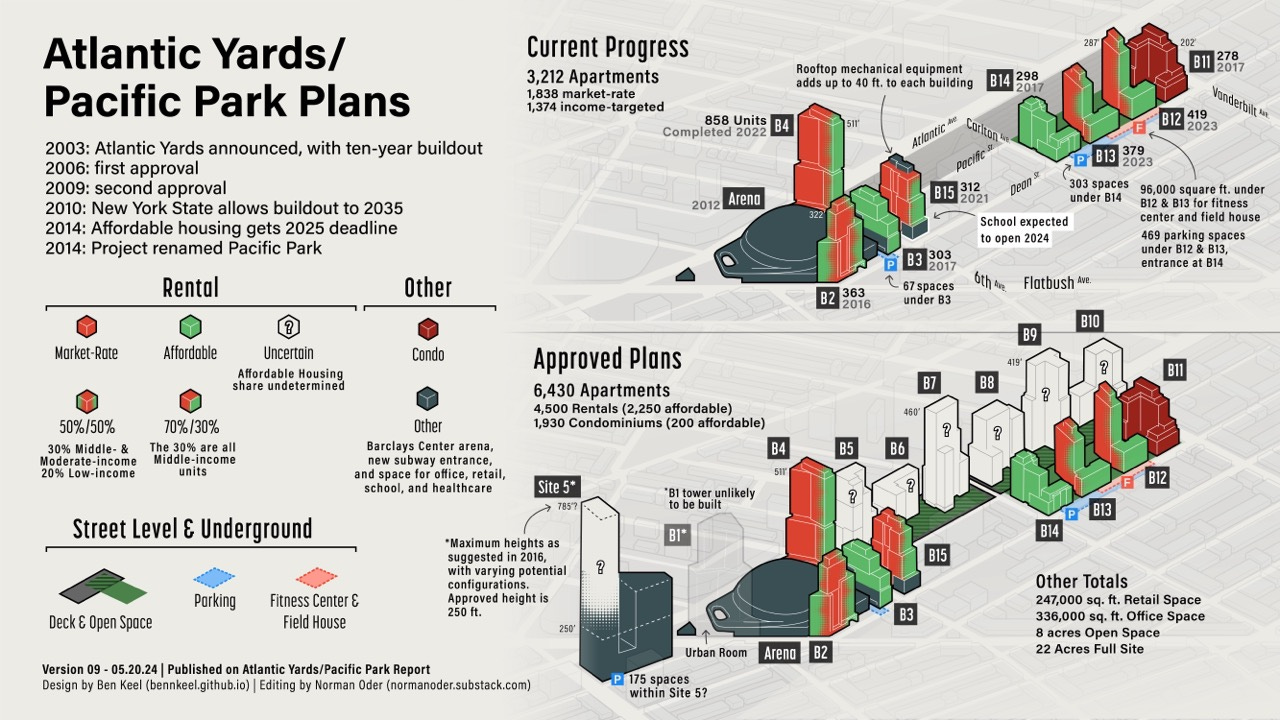

After a settlement in June 2014 setting a new 2025 deadline for the affordable housing, the new joint venture Greenland Forest City Partners produced a map (below) projecting that the last railyard tower, B5, would be finished by 2025. (Note: the study wrongly states that the 2025 deadline was agreed to in 2009.)

The map, in hindsight, was not just absurdly optimistic regarding the housing market, but willfully blind to the challenges of building the B1 tower over a working arena.

Also, it omitted a date for Site 5, the parcel catercorner to the arena. In 2018, well after the stall caused by new competition nearby, the joint venture finally acknowledged, in a filing to state regulators, that completion was projected “by 2035.”

That said, if Forest City had been a private company with a longer time horizon and a better grasp of sports team ownership, it might have held onto the Brooklyn Nets and cashed out on that scarce commodity, as Mikhail Prokhorov later did, selling to Joe Tsai, and Tsai partially did, selling to the Koch family.

Forest City’s profits might even have cross-subsidized the platform and the affordable housing, without exhausting profits.

Moreover, had New York State structured project contracts so they could be revisited, the state might have captured some of the upside from the rocketing value of the Nets and the arena company. I still think ESD has leverage.

(Note: while the study claims that “All subsidies and tax incentive programs were designed to increase the affordability of the project and ensure that developers provided public benefits on the site,” I find that dubious, since significant public support—subsidies, tax breaks, low-cost financing—went to the arena.)

“Major Elements”?

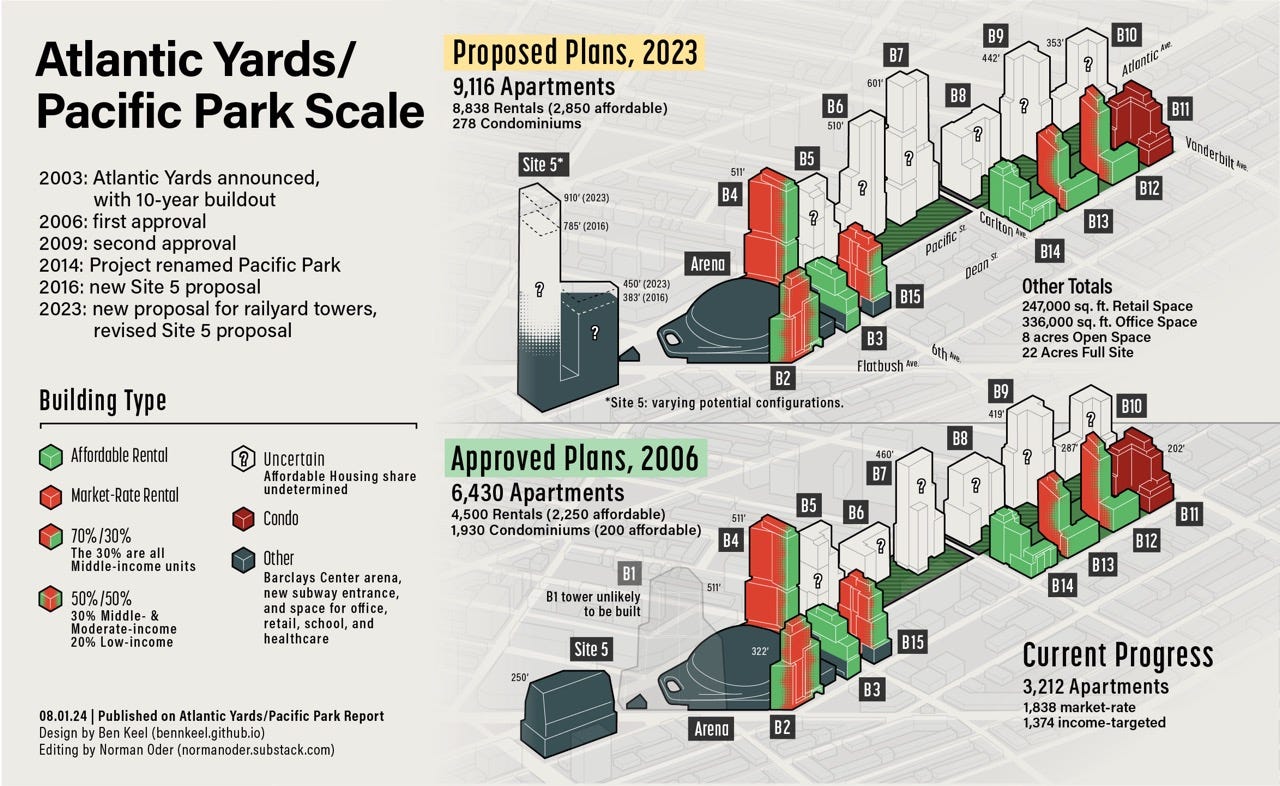

As to the "Major Elements" of the “General Plan Agreement” cited in the study, the table below is confusing. The project was approved with 6,430 apartments in total, including 2,250 affordable rentals, 2,250 market-rate rentals, and 1,930 condos, which could be flipped to rentals.

Where did they get their unsourced unit counts? Well, it’s partly my fault, I think—an awkwardly written paragraph in this article focused on the units left to build, not the total approved. Elsewhere, the study accurately cites 2,250 affordable rentals “out of approximately 6,400 total units.”

While the MGPP did include the Urban Room, a glass-enclosed atrium for indoor—not outdoor—gatherings, it was traded for a temporary plaza when the arena opened in 2012. It's perplexing that this goes unmentioned.

Today, the plaza looks to be made permanent. The question is whether the arena operator will get it for free.

The "stadium"—actually, an arena, which is enclosed—was approved with 18,000 seats for its main tenant, the NBA’s Brooklyn Nets, with capacity of more than 19,000 seats for certain events.

Yes, the plan included community facility spaces, such as a health care center. But the latter, I reported, is just a medical clinic, with no announced provisions to serve low-income patients, as initially promised. How much research did they do?

The public school was not developed in the B12/B13 towers, as the study suggests, but in the B15 tower.

No, the arena was not required to have a green roof, as the study suggests. In fact, the arena opened with a rubber roof, as shown above, but the green roof was added to tamp down on noise escaping from the arena.

Key contrasts: EB-5

Consider a chart from the study (below) comparing Hudson Yards and Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park, which I’ve highlighted. At the bottom, under "EB-5 investor financing," the chart states “Yes” for both, implying roughly commensurate experiences.

Not at all. Related raised more money via EB-5 than any other project, nearly $1.6 billion, compared with $577 million with Atlantic Yards. (Other sources say Related raised $1.2 billion.)

Notably, Related set up its own regional center, or fundraising middleman, rather than relying on others. Moreover, as far as we know, the investors have not been paid back, nor is such payment required, given the terms of the agreement.

(Arguably, the Penn researchers didn’t know of the lack of repayment, news of which surfaced in June 2020, months before the paper was published.)

The study states, wrongly, "Atlantic Yards received $228 million through the EB-5 program. All funds were paid back by 2020." Actually, there were three rounds of funding, totaling $577 million and only the first round, via the New York City Regional Center, was paid off.

(Note that the EB-5 investors each put in $500,000, not the $900,000 minimum cited in the study, which uses the current investment floor.)

The failure to repay the second and third rounds is why the six railyard sites are in foreclosure. Now the intermediary “regional center” for the Atlantic Yards investments, the U.S. Immigration Fund (USIF), has held all the cards, and is forming a joint venture with Fortress Investment Group and Related.

(With Hudson Yards, Related controls the regional center and has organized the investment so that failure to repay does not threaten loss of their property.)

Key contrasts: location

The study sites the project “at the center of four distinct neighborhoods – Park Slope, Fort Greene, Clinton Hill, and Prospect Heights.” Um, it’s mostly in Prospect Heights, bordering the first three neighborhoods, as well as Boerum Hill and Downtown Brooklyn.

The chart above contrasts Central Brooklyn with Midtown Manhattan. The authors write:

Pacific Park is located in central Brooklyn, surrounded by low-rise residential neighborhoods and local retail. Re-zoning the area would change the fabric of the area significantly, ranging from transit usage to daylight loss from large tower shadows. The site parcels were the only [sic] remaining part of the 40 year old urban renewal area that had not been redeveloped. Pacific Park is a new development but not a new “neighborhood”.

(Emphases added)

Wait a second. Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park is located mostly in Prospect Heights, near the edge of Downtown Brooklyn, with large malls, Atlantic Center and Atlantic Terminal, immediately north of the arena block. That’s not local retail. There is local retail in adjacent neighborhoods like Park Slope and Prospect Heights.

Nearby Downtown Brooklyn has been transformed in the last 20 years with high-rises thanks to the 2004 Downtown Brooklyn rezoning. Even if that had barely started when Atlantic Yards was approved, the authors should have acknowledged it.

Remember, in 2016, Forest City, by then the junior partner in Greenland Forest City Partners, unilaterally announced it would pause Pacific Park, blaming "an almost unprecedented concentration of new rental supply" nearby, plus uncertainty around the 421-a tax break and rising construction costs.

While Forest City initially placed Atlantic Yards in Downtown Brooklyn, and the Downtown Brooklyn Partnership still claims the project, the developer—most recently Greenland—has tried to call Pacific Park its own neighborhood.

Today, however, the landlords mostly claim Prospect Heights, as shown in the screenshot above. The arena’s arguably at the edge of Downtown Brooklyn.

(Note: the Penn Institute for Urban Research’s 2020-21 annual report, oddly enough, locates the project in Fort Greene.)

A rezoning?

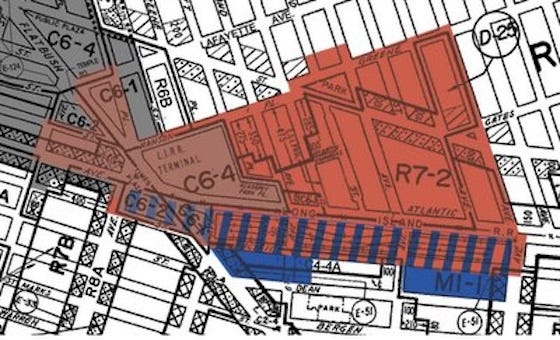

Despite the study’s use of the term “re-zoning,” Atlantic Yards was not rezoned by City Council. Rather, city officials encouraged an override of zoning via Empire State Development Corporation (now Empire State Development), a state authority overseen by the governor.

That meant an easier path to approval and no votes by local elected officials.

The 22-acre project site includes the remaining part of the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area (ATURA), but, crucially, added pieces outside ATURA, thus prompting challenges to the use of eminent domain.

(No, contra the study, the state did not extend the ATURA boundaries. That would’ve been a city responsibility.)

Midtown Manhattan?

Regarding Hudson Yards, the authors write:

Hudson Center, in comparison, was in far west midtown Manhattan along the river and adjacent to Javits Center, the city’s largest convention center with over 2.2 million visitors each year. The project sits in a larger city development plan between 42nd and 30th street dominated by Lincoln Tunnel infrastructure and manufacturing. Without a subway line the site was isolated from any low-rise residential areas. The site was re-zoned from manufacturing to match the adjacent midtown business district and the area was marketed a totally new 21st century neighborhood where none existed before.

Yes, that's a far easier site to develop, in terms of competition. As the authors indicate, it was marketed as a new neighborhood, which it was—less a part of Midtown Manhattan than an enclave.

Railyard platform

Yes, there's a big difference between the platforms. As the authors state, "Hudson Yards... is built over railyards 100% owned by the MTA [Metropolitan Transportation Authority] and negotiated in a single $1 billion transaction."

Well, “would be” built. Only about half of the 28-acre site has been completed; the Western Rail Yards awaits a platform.

(Also, a small part of the site, for 10 Hudson Yards, was terra firma, as the study acknowledges, so no platform was needed. Thus, the platform was less than the 28 acres cited.)

The table above suggests the railyard platform over the MTA's Vanderbilt Yard in Brooklyn is 8.6 acres. I’ve typically used 8.5 acres to describe the railyard site, and the study also uses that figure, though the total is about 8.425 acres.

However, those small discrepancies aren’t the issue. The Vanderbilt Yard originally encompassed parcels on three blocks, from Fifth Avenue to Vanderbilt Avenue, between Pacific Street and Atlantic Avenue.

In the western block, the Barclays Center and the B4 tower (18 Sixth Ave., aka Brooklyn Crossing) were built below-grade, in the base of the railyard, with no platform needed.

That allows visitors in the best seats, near the arena event floor, to walk down stops, and also mitigates the scale of the building.

So a platform wouldn’t cover 8.5 acres, just the remaining two blocks. Presumably the MTA’s initial calculation already recognized that the block between Sixth and Carlton avenues contains significant amount of terra firma jutting south from Atlantic Avenue.

The second block, between Carlton and Vanderbilt avenues, also has a small piece of terra firma, just west of Vanderbilt.

How many acres for development?

The table above suggests that Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park has only 7.5 acres for residential/commercial space, plus 8 acres of open space and 6.5 acres for the “stadium.” (I’d appreciate sourcing here.)

The arena’s surely not 6.5 acres. This Department of Buildings document describes an arena block of 325,360 square feet, nearly 7.5 acres.

However, that block was designed to have four buildings flank the arena. Three have been built, while the largest parcel, for B1 (aka "Miss Brooklyn") is now used for the plaza. However, the bulk of B1 likely will be moved across Flatbush Avenue to Site 5.

Bottom line: there's more acreage for residential/commercial use than stated.

Flaws in the analysis: the CBA

The authors write:

Initially, the developer’s work with the ACORN group to define a Community Benefit [sic] Agreement was groundbreaking. Atlantic Yards was the first time a developer has [sic] done this type of outreach in the region. It looked pro-active and appeared to be a generous list of services such as community center, a healthcare facility, and public space. In the end, those services actually did end up in the General Plan Agreement.

Yes, the Community Benefits Agreement (CBA), with eight signatories--a few established groups such as ACORN, plus mostly new, essentially astroturf ones--initially drew praise. It also provoked skepticism, given the hand-picked counterparties, opaque process, and funding from the developer.

Were the services “generous” or calculated? The promise of a "community center" (seniors and youth) was pushed off to the late phase of the project. The "public space," backloaded to the end of the project, can barely keep up with the increased population, its impact likely diminished if the project gets supersized.

Yes, the community facilities and open space were part of the MGPP. (Again, not the “General Plan Agreement.”) However, crucial promises in the CBA, notably the configuration of affordable housing and job training, were not incorporated into any governmental document.

The study states, “Although the private developers entered into a unique ‘agreement contract’ with a local group called ACORN, it was not legally enforceable.” Not true. The CBA, which incorporated an initial non-binding Affordable Housing Memorandum of Understanding with ACORN, was enforceable only by the counterparties, which were dependent financially on the developer. So they didn't try.

Overstating opposition

The authors overstate the opposition, writing:

However, those benefits were outweighed by controversy over the government’s involvement in [sic] stadium. First, opposition to the government’s financial stake in the project was not just local, but regional and national. In 2006, after much debate, the U.S. Internal Revenue Service made a ruling that PILOT [payments in lieu of taxes] bonds could not be used for private activities such as arenas. This ruling was national-wide. However, because the Atlantic Yards agreement was approved by the State of New York before the ruling, the project‘s 2009 bond offering was ‘grandfathered’ and allowed to proceed despite city-wide opposition.

The opposition to government support was local, focused in Brooklyn neighborhoods nearest the project site. It was hardly citywide, as polls showed a shift to general support. The political powers backed Atlantic yards vigorously.

Yes, a national policy change, not focused on Atlantic Yards, threatened to impede it, but it did not reflect opposition by any national figures. In fact, lobbying by key New York State elected officials helped get the bond offering grandfathered in.

The study erroneously states that Atlantic Yards was approved by New York State before the IRS ruling. Rather, a Treasury regulation banned PILOTs for new projects, but allowed them for "certain projects substantially in progress"—defined as having gained preliminary approval by Oct. 19, 2006.

Even that notion of “preliminary approval” was debatable. The city and state argued that the state’s routine "adoption" of the General Project Plan three months earlier—without public comment or board discussion—represented initial approval.

Regarding eminent domain

The authors write:

The decision by the State of New York to assemble properties using eminent domain was also bitterly fought by local residents, resulting in several court cases. Though some were dismissed, one was the appealed all the way to the State Supreme Court. Although the courts decided in the State’s favor, the fights took years to adjudicate and slowed the project at the most basic level – property rights. The developer’s proposal was ‘all-or-nothing’ – that is, the financial strategy required ALL the property in order to work. Without flexibility, the phase 1 arena was on hold as well as phase 2 residential towers.

The authors' general point is sound: because (almost) all the property was required, legal fights could delay the project. (Then again, the delay did help the arena, since it opened after the recession.)

But they get some details wrong. There were two main cases. One started in federal court and was dismissed at the appellate level, with the U.S. Supreme Court declining to take a further appeal.

The other started in the Appellate Division of the state Supreme Court, rather than the state Supreme Court, which is trial court. That common error obscures how condemnors are privileged in New York State.

Here, eminent domain cases are fast-tracked and decided based on submitted papers and oral argument, not any fact-finding process involving cross-examination of witnesses.

The dismissal of that case prompted an appeal not to the “State Supreme Court” but rather the state's highest court, the Court of Appeals in Albany.

Questions of density

From the study:

Pacific Park will have 6.6 million square feet of residential/commercial and 8 acres of open space. Hudson Yards has a much higher density (11 FAR). It will have 20 million sf of residential/commercial and 14.5 acres of open space. The higher density at Hudson Yards allows for larger financial returns on similar lot sizes and more flexibility to handle setbacks such as delays or market shifts.

That’s a significant difference. Note that Hudson Yards has major office towers and less of an affordable housing commitment.

Though the study doesn’t mention it, the Floor Area Ratio (FAR) of Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park would be 7.8 (9.0 without the streetbeds incorporated into the project site). FAR measures bulk as a multiple of the underlying lot.

That actually undersells it, since the arena has a lesser FAR, allowing certain parcels, like B4 and Site 5, to have Floor Area Ratios far greater than the average.

Since then, however, Greenland USA sought to supersize the project and the next developer, likely Related, likely would do so too, elevating the overall project FAR. As proposed, Site 5 would have an FAR of 25.5, more than double the maximum FAR in the Downtown Brooklyn rezoning.

Public transportation investments

From the study:

Unlike Hudson Yards in Manhattan, the city was not willing to take on debt and risk for transit investments at Atlantic Yards. At Atlantic Yards the real estate developers agreed to pay for MTA Vanderbilt Yard upgrades and the platform investments. (estimated over $200 million). At Hudson Yards, the city agreed to the first subway extension in 60 years. The city agreed to spend $2.4 billion on a new extension of the 7 Subway line and a new station in the center of the development. It is the only subway stop west of Ninth Avenue,

That's a significant difference though, as noted, Atlantic Yards gained $100 million for infrastructure from the state, plus another $205 million from the city that could be used for land purchases or infrastructure.

Forest City, and then Greenland, made the unwise calculation that the value of the development rights, if exercised on their expected schedule, would easily pay for the infrastructure. (Greenland, according to The Real Deal’s interview of formerly Deputy Mayor Alicia Glen, also was more focused on the opportunity to build condos than the obligation to build affordable housing._

Note: the city didn’t agree to “spend $2.4 billion” on Hudson Yards but rather to back up annual bond payments of the Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation, fueled by revenue generated by new development projects in an area around the 28-acre project.

The city has both made backup payments and, more recently, taken in a surplus. I’m not sure of the overall accounting, but it’s fair to say Hudson Yards had a safer deal.

Getting the public partnership wrong

From the study:

The primary public partner at Pacific Park is the State of New York, which only took an active role in the first Stadium phase. The City of New York has taken an active role in the entire Hudson Yards process. The subway line extension was approved in 2005 and completed only 2 years after Hudson Yards broke ground. The city created a special district fund and two investment corporations to help manage related infrastructure projects, as well as taking on larger financial risks - e.g. Bond interest repayments out of its General Fund in the event of project delays.

Yes, the city took a far larger funding rule in Hudson Yards.

However, the State of New York did not limit its “active role” to “the first Stadium phase.” Rather, Empire State Development has remained involved, from enabling eminent domain to approving project changes, throughout the life of Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park.

That continues, as we await the next project change.

Role of the AY CDC?

In the bottom left of the chart below, the study gets a big thing wrong.

The document states:

State of New York - via New York Empire State Development (ESD) and its subsidiary Atlantic Yard [sic] Community Development Corporation (AYCDC)- is the primary public partner in Atlantic Yards. ESD is the State of New York’s development agency, with regional offices promoting business investment and job creation through loans, grants, tax credits, real estate development, and other forms of assistance.

AYCDC is a non-profit subsidiary of ESD. AYCDC was created in 2014 to oversee the General Plan Agreement, ensure all civic projects and affording housing requirements are met, and negotiate amendments. The AYCDC Board is also responsible for managing the PILOT municipal bonds that provided low-cost construction financing for the arena.

The ESD and AYCDC have substantial legal powers as a public property owner.

No, the bonds are managed by the Brooklyn Arena Local Development Corporation (BALDC), an ESD alter ego.

The AY CDC (my acronym) negotiates nothing and ensures nothing. Its oversight is advisory. It was set up to, among other things: review proposed project changes, and advise the ESD; monitor developer compliance with all public commitments; and monitor construction impacts and quality of life issues. It has only intermittently done that.

Competition or not?

From the study:

Forest City Ratner had a lot of money on the line [sic] their Atlantic Yards Proposal and was vulnerable to shifts to local market conditions. New local development grew. The historic Atlantic Terminal Building was rehabilitated and opened with 370,000 square feet of retail space. The Bank of New York Building one block away opened with 470,000 square feet of office space.

This is also off. The Long Island Rail Road's historic Atlantic Terminal had been demolished, but the new Atlantic Terminal mall on that site, with the Bank of New York building attached, were developed by Forest City itself.

The developer saw these as complementary, not competition.

Timing issues

From the study:

Commercial space was years away after the Nets basketball stadium was completed. Deadlines for affordable housing units in the General Agreement meant front-loading the schedule with lower-priced units and delaying luxury towers. With the 2008 financial crisis the national residential market was in crisis. At 462 Dean Street the city received over 84,000 applications for 184 units. The cost of railyard renovations needed to be factored into the financials. The project could no longer factor in long-range stadium profits, because the stadium was sold at a loss. The first residential tower was also an untested design concept. Construction problems with its partner Skanska let to delays and lawsuits.

Yes, commercial space was years away, but the developer had previously traded office space--in at least three of the four towers flanking the arena--for condos. The only building(s) left for office space would be B1 and Site 5.

As to 461 Dean (not 462 Dean), the number of applications was not atypical; any building with low-income units gets inundated with the same applicants. The real issue is how few people actually apply for middle-income "affordable" units.

Note that the 461 Dean lottery was not, as the study suggests, limited to “eligible city employees.” The second building was 535 Carlton, not, as the study suggests in one place, 525 Carlton. Nor is it alternately known as 670 Pacific.

The vaguely referenced “construction problems” involved an untested process for modular construction.

Arena loss?

Was the arena "sold at a loss"? Well, sort of. First, Forest City never owned the arena--given nominal New York State ownership, to enable tax-exempt financing and land--but, rather, the arena operating company.

Forest City kept a 55% share in the arena company and sold the rest to Mikhail Prokhorov in a complicated transaction involving 80% of the Nets. Was that a loss? Probably.

The remainder was sold to Prokhorov, announced in December 2015, valuing the arena company at $825 million. Given that the arena, with associated improvements, had cost $934 million, that indicates another loss.

Ironically enough, the arena company is now worth nearly double that, thanks to Tsai's purchase from Prokhorov, and then a new investment from the Koch family.

Greenland’s false hopes

The study's final sentences:

The instability of Forest City Ratner’s financials mean that the schedule was delayed by company buy-outs, the stadium sale, finding new partners and venture agreement negotiations. The new project owner, Greenland Holdings, has much deeper pockets. It’s a state-owned enterprise and publicly traded company on the Shanghai Exchange. In 2016 [sic] has a valuation of 733.1 billion CNY. Hopefully, this cash infusion means the project will meet its deadlines, and Atlantic Yards, - now Pacific Park – will finally complete the original developer’s vision of a vibrant dense node of housing, public events and retail in the center of Brooklyn.

Well, the original vision was “Jobs, Housing, and Hoops,” with 10,000 office jobs. That was abandoned fairly quickly.

This paragraph reads like it was researched before the project's 2016 pause and 2018 restructuring, with Forest City’s almost-complete exit.

As of August 2020, not long before the study was finished, Greenland had been rising in annual rankings from Forbes and Fortune, but its credit rating was plummeting, so its pockets were no longer deep. It has since plunged in those rankings.

About that vision

The original developer’s vision has been compromised, and revised, multiple times. I get that urban enthusiasts like the Penn authors would like to see projects completed.

At a panel in New York in 2008, Birch expressed enthusiasm, with only mild caveats, at authoritarian China’s enormous progress with infrastructure.

Facing pushback, she acknowledged the need “to get to decisions that will balance citywide needs with neighborhood needs. And that’s something we have not figured out how to do.”

That remains true.

However, the lessons of Atlantic Yards today include not merely how “to get to decisions” but also the need for oversight. More transparency and accountability might balance the relationship between developers and state authorities often willing to bend.