Could NY State Leverage Naming Rights to Get ArenaCo Owners Tsai (& Koch) to Pay?

Empire State Development could end the Barclays Center sponsorship. (Shh--the bank's a felon.) It might even be a win-win.

I previously argued that New York State had essentially ceded the Barclays Center plaza—er, Ticketmaster Plaza—to the arena operating company, but was not obligated to make that permanent.

That meant the billionaire owners of BSE Global, the families of Joe Tsai and Julia Koch, should pay for the privilege of using the plaza, which was never formally transferred.

Yes, the arena operators were to get revenue from signage and naming rights at the once-planned Urban Room, the public atrium attached to the never-built flagship tower, in a partial parallel to its more extensive deployment of the plaza.

However, the open-air plaza, without sharing space with the tower or being disrupted by construction, surely offers more benefits. See how it was truncated, below, before Sunday’s New York Liberty playoff game.

I also argued that Empire State Development (ESD), the state authority that oversees/shepherds the project, had leverage over extending the “You Belong Here”/”We Belong Here” neon signage, by Tavares Strachan, installed over the plaza’s transit entrance in October 2021 for a 3-year term (well, 3+ years!) until the end of this year.

That’s not the only leverage New York State has for the owners of the increasingly valuable arena company and sports teams to contribute to the public interest.

Naming rights value

Consider arena naming rights, purchased by the British bank Barclays for $200 million over 20 years, after initially pledging $300 million for an arena designed by starchitect Frank Gehry.

The deal was renegotiated after Ratner, which was later dropped for a smaller, cheaper venue designed by Ellerbe Becket and rescued by SHoP.

That deal, starting in 2012, may seem a bargain, given that the 2020 naming rights deal for UBS Arena at Belmont Park, a hockey-centric arena in the Long Island suburbs, is reportedly $15 million a year and the just-opened Intuit Dome in Inglewood, CA, outside Los Angeles, is reportedly $21.7 million a year.

The New York Post in May 2021 reported rumblings that Tsai, at least when the Brooklyn Nets had a trio of superstars and enormous buzz, was seeking a more lucrative naming rights agreement.

After all, the franchise soon saw departure of one-year jersey patch sponsor Motorola, which had paid more than $10 million for a year (estimated), while the new deal with Webull was (reportedly) $30 million a year, the largest in the league.

That covered uniform patches and more for the Brooklyn Nets, the New York Liberty, the minor league Long Island Nets, and even the gaming crew. (That didn’t last, since the Liberty now have a patch deal with Barclays.)

Ejecting Barclays

Perhaps there’s a win-win, at least for the public and the arena company, if not for Barclays.

Maybe even for them, too. The British bank never opened a retail banking division in the United States, so it’s been a costly brand-building project with, perhaps, limited returns.

ESD has more than enough grounds to eject Barclays, an admitted felon for manipulating the foreign exchange market, from the naming rights agreement, as I argued in City & State in September 2015.

The state’s not supposed to allow contracting with a Prohibited Person, and Barclays sure seems to qualify. Beyond the felony plea and a criminal fine of $650 million, Barclays paid nearly triple that in civil fines.

I never could get anyone in state government to disagree with my argument, but no one sought to short-circuit the naming rights deal.

Similarly, evidence suggests that Nicholas Mastroianni II, head of the investor visa company U.S. Immigration Fund, also qualifies as a Prohibited Person, given his criminal record.

That means ESD should never have allowed him to broker two loans, under the EB-5 program, to developer Greenland USA (and, at the time, Forest City). Instead, he’s slated to be part of a joint venture, with Related Companies, to develop six tower sites over the Vanderbilt Yard.

A new locational identifier?

Sure, ditching Barclays would mess with an arena name a lot of people use, but the names of sports venues can change regularly. (Hey, Staples Center in Los Angeles is now Crypto.com Arena.)

So a new arena sponsor—let’s say Coinbase, just for kicks—presumably would require new signage, and a name change for the adjacent transit hub.

It was renamed Atlantic Av-Barclays Ctr after Forest City Ratner--remember, the arena builder, original operator, and original master developer--bought naming rights for $4 million over 20 years, matching the Barclays deal term.

I’m not sure whether the current arena operator is paying now, but the Tsai/Koch BSE Global could easily swing it. Remember, the Barclays agreement has only eight years left. So it might expire anyway.

A new deal

If Tsai/Koch can reap more revenues from naming rights—and they should, thanks to overall inflation and even the growing prominence of the WNBA’s New York Liberty—why not ensure the public gets some of that? It wouldn’t be the first time.

A few jurisdictions with publicly assisted venues get a cut of naming rights, though, admittedly, in Denver a 75% public share of stadium construction surely makes a stronger case than in Brooklyn, where the direct subsidy, for land and infrastructure, was closer to 20%.

Then again, as I’ve established, the issue in Brooklyn goes well beyond the direct subsidy but includes tax-exempt land, tax-exempt financing, eminent domain, and other discounts.

Indeed, including some of that, notably the financing, helped the Downtown Brooklyn Partnership claim $686 million (!) in arena public support. Doesn’t that justify a public share from naming rights revenues?

No assessment

In the case of the Brooklyn arena, the value of naming rights was never factored into financial analyses of the project.

At a July 2009 public Q&A regarding the project, the moderator read a question that I submitted: "Why will [original developer] Forest City Ratner get to keep the naming rights revenues for what the ESDC claims will be a publicly owned arena?"

“It’s part of the financing for the project,” responded Steve Matlin, a lawyer for ESD, depositing the microphone on the table to accentuate the brevity of his response.

For what project: the arena itself, or the overall Atlantic Yards project?

Either way, that bolsters my argument.

Naming rights helping the project

If the naming rights revenues were supposed to help finance the full project, the separation between the arena company and the project’s master developer—achieved when original developer Forest City sold the arena operator (and team) to Mikhail Prokhorov—ended that alliance.

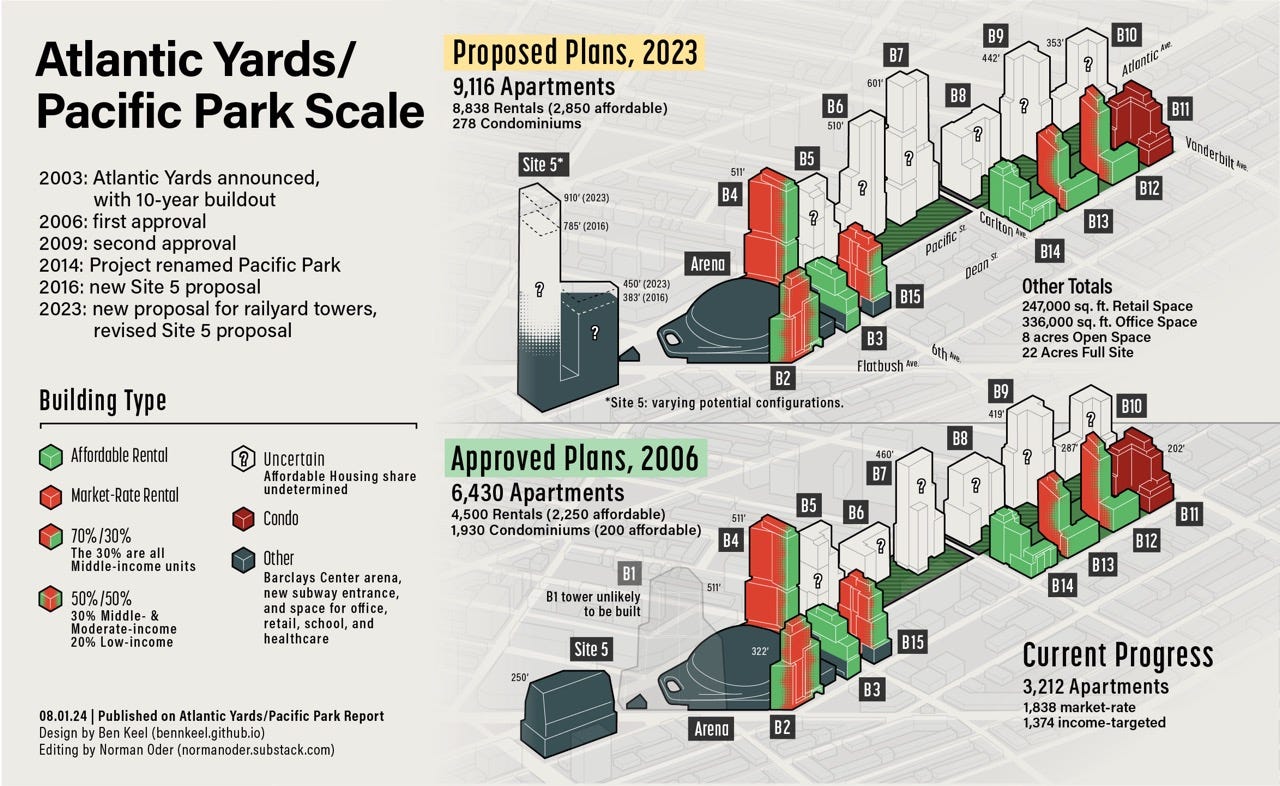

ESD could restore that conceptual share, and thus ensure that some naming rights revenues support the public interest, such as more deeply affordable housing and/or a share in the platform, without having to supersize the project as proposed last year.

Heck, it’s arguably already supersized.

Naming rights helping the arena

If the naming rights revenues were supposed to help pay for the arena, well, there’s a lot of cushion there, so some funds could be steered to the public interest.

After all, the arena was said to be valued at $1.5 billion (some 60% more than construction cost) in the Tsai-Koch transaction, which brought $688 million to Tsai’s holding company, including the Nets, the Liberty, and more.

So, even if the arena has consistently been less profitable than projected, that’s been made up by the cash infusion.

And the next naming rights deal surely would be more lucrative.