Would Joe Tsai's Slickest Move Be Poaching Ticketmaster Plaza?

Keeping the branded plaza bolsters Barclays Center operations & revenues. State authorities have more leverage than they admit. Why not map it as parkland & charge a licensing fee?

In my June 25 essay in Common Edge regarding the new Koch family investment in BSE Global, parent company of the Brooklyn Nets, Barclays Center operating company, and New York Liberty, I suggested that those benefiting from the huge increase in the value of the teams and arena, the families of Joe Tsai and (secondarily) Julia Koch, owed the public.

Perhaps, I wrote, the newly enriched Tsais (by $688 million) and likely to be enriched Kochs could cough up $300 million-plus for public construction (and ownership) of that unbuilt, two-block railyard platform—a base for six future towers—and help get the delayed affordable housing built.

Sure, that sum was fanciful, but the framing has validity, since public assistance—including eminent domain, direct subsidies, tax-exempt land, tax-exempt financing, and the ability to sell naming rights and advertising—made the arena viable and helped fuel BSE Global’s inflated valuation. (Let’s not forget opportunity costs.)

More money coming

The Kochs weren’t stupid, since they had to know more revenues were coming. An expected NBA expansion by two teams, paying at least $4 billion each, means at least $267 million per ownership group, Forbes estimated last October.

The NBA just secured, according to The Athletic, an 11-year media rights deal worth $76 billion. (Omitted: local TV.) That $6.9 billion annual payment, shared among the 30 teams and with 51% to players, is more than 2.5 times the current $2.7 billion deal.

That works out to $230/million annually per team, with $112.7 million to the owner. Or, perhaps, $215.63 million/$105.66 million after expansion.

What about the plaza?

The more I’ve looked into it, the more leverage New York State has, especially over what’s now called Ticketmaster Plaza, a privately operated and often publicly accessible space crucial to arena operations.

That space, an “interim condition” that boasts a sponsor, lucrative signage, and other promotional activities, was never subject to public comment or full assessment.

However, Empire State Development (ESD, formerly ESDC), the gubernatorially controlled state authority that oversees/shepherds Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park, has quietly ceded the plaza to the arena operating company, part of BSE Global, with no compensation, and looks to do so permanently.

If so, that would be a giveaway.

Premised on common ownership

The “temporary” plaza was implicitly predicated on the common ownership—no longer valid—of the arena operator and the project’s master developer, originally Forest City Ratner.

Before building Barclays Center, which opened in 2012, the arena company was simply granted the plaza indefinitely, since it was coupled with the overall right to develop a giant office tower, aka B1, with an atrium, known as the Urban Room, effacing the plaza.

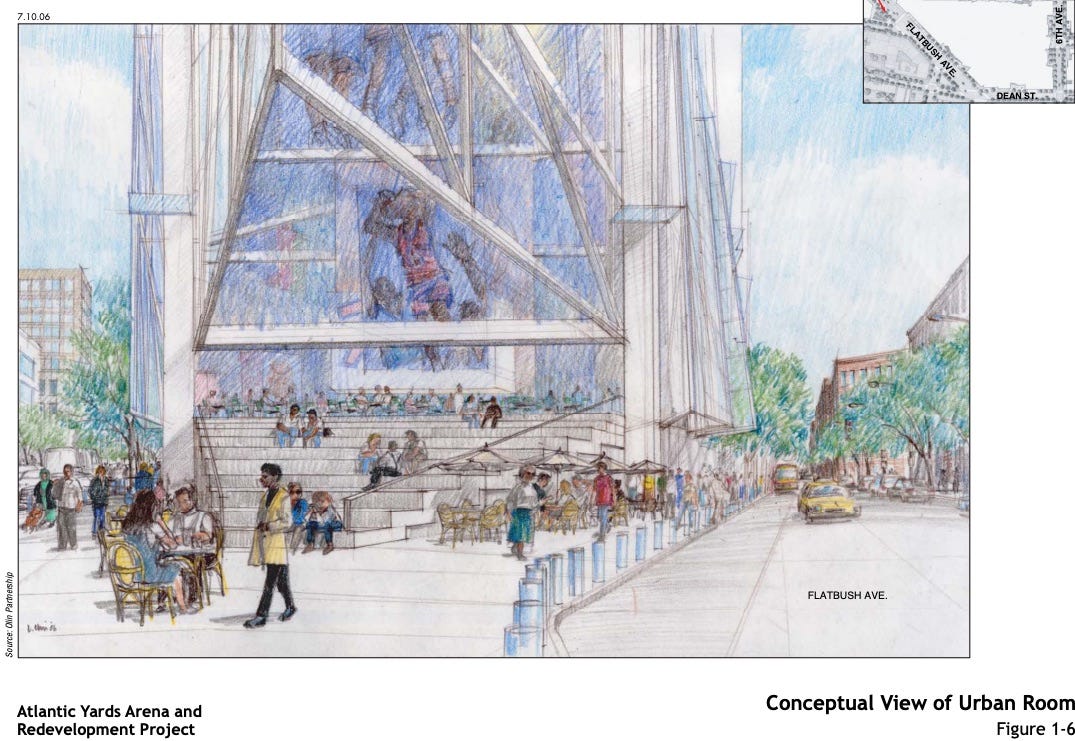

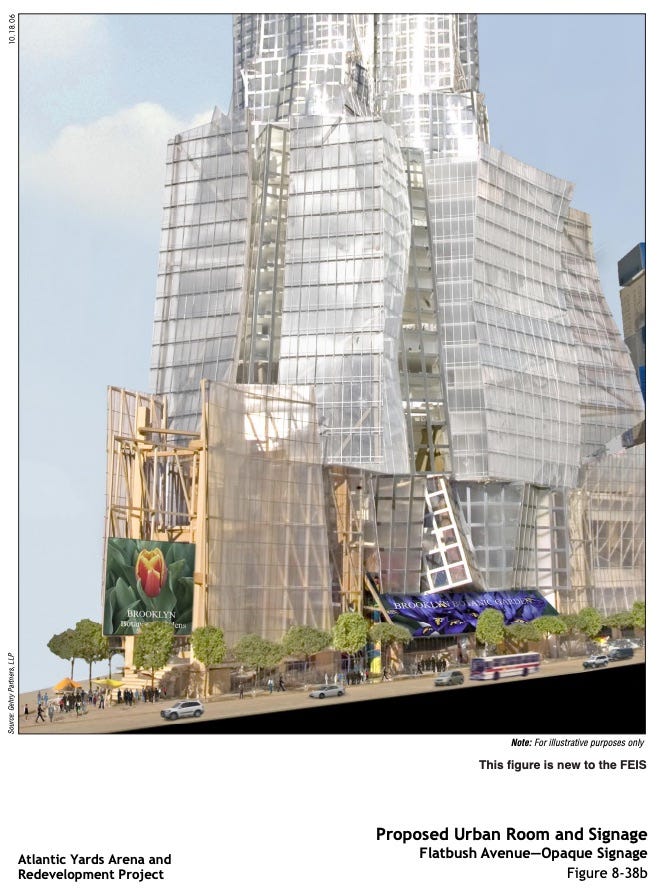

An illustration in ESDC’s June 2009 Technical Memorandum made the replacement plaza look quite green, with far more trees than advertising.

That document made project sponsor Forest City responsible for both the Urban Room and the interim substitute:

The potential delay in the completion of Building 1 would have certain implications for arena operations as well as for the construction-period uses of this building site. The uses identified for the Urban Room would still be provided; the urban plaza would still serve as a new access point to mass transit… providing new escalators, an elevator, stairways, and passageways leading to the subway station below… [T]he plaza also would include small kiosks for retail and café uses... This interim use of the Urban Room area would be designed by the project sponsor to provide a usable, welcoming amenity for the surrounding neighborhood.

(Emphasis added)

Update Aug. 11: I should acknowledge that the arena company was supposed to benefit from Urban Room signage and use of part of it as a box office, plus gain naming rights Yes, that's a partial parallel to its more extensive use of the plaza. However, it was to be shared.

So it's clear that the open-air plaza, without sharing space with the tower, offers more benefits. There's a huge advantage to having the arena, rather than the tower, as a focal point.

The impact of decoupling

The arena company, however, was soon decoupled from the rest of the project, since, by 2015, Mikhail Prokhorov took over full ownership, bought out in 2019 by Tsai.

The failure to build the Urban Room should have generated fines of $10 million imposed on Greenland, but ESD has chosen not to enforce that contractual provision.

Had ESD publicly considered waiving the fines while making the plaza permanent, that might have highlighted the sleight-of-hand giveaway to Tsai—and the argument for making the beneficiary pay for the privilege.

Value to the arena

It’s clear that parcel was never meant to primarily benefit the arena. But it’s crucial, enhancing the guest experience and allowing space for promotions and advertising.

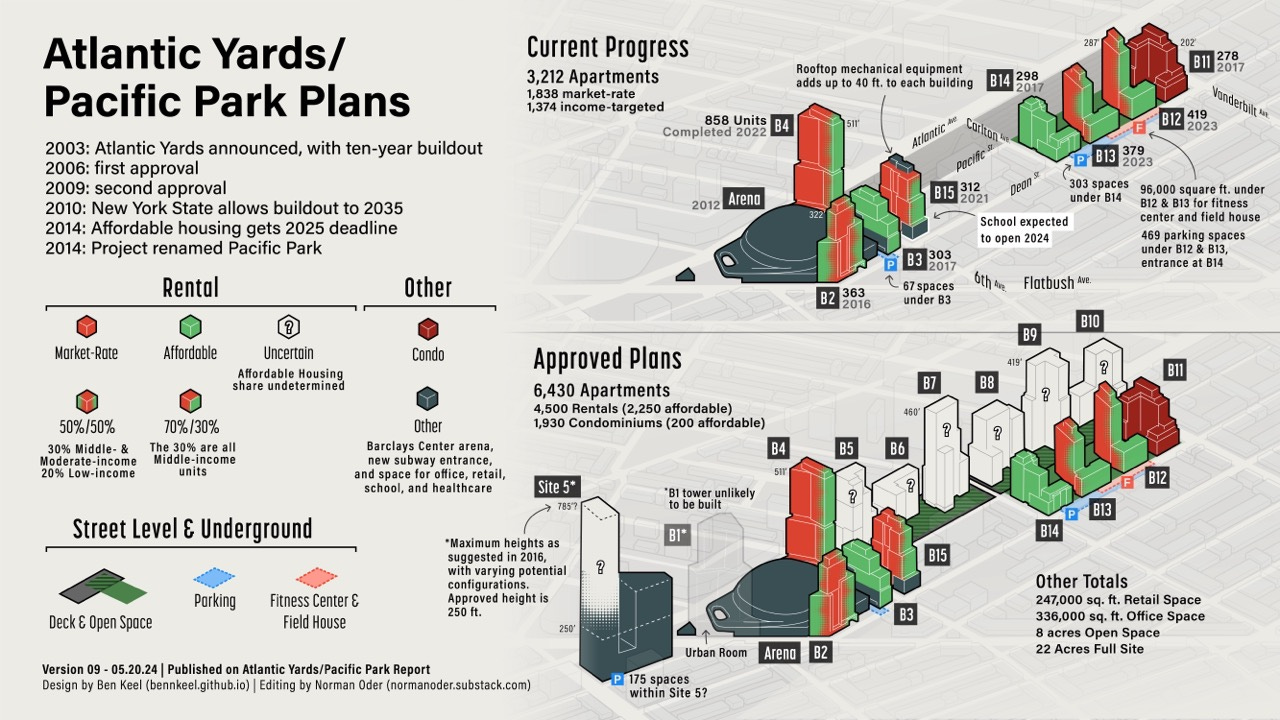

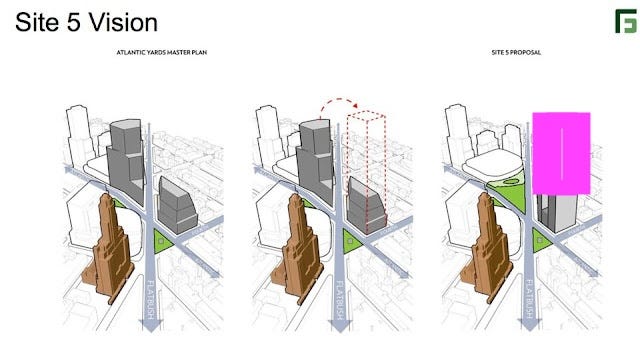

State officials likely will be soon asked to justify transferring the bulk of the unbuilt B1 tower—which original architect Frank Gehry dubbed “Miss Brooklyn”—across Flatbush Avenue to what’s known as Site 5, to enable far larger towers than approved. One justification: the civic value of preserving the plaza.

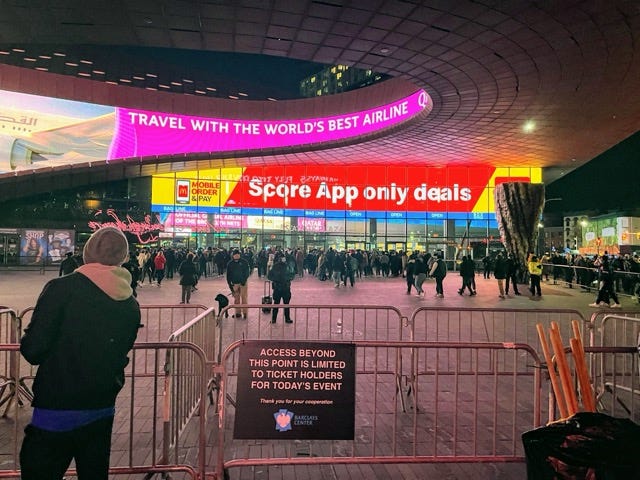

Yes, the plaza serves a crossroads, transit entrance, and even sometime protest location, as it was “totally appropriated” in 2020, according to one organizer. But that’s trumped by commercial value. For example, the plaza’s cordoned off to manage arena access during events, and used as a canvas for various promotions.

Previous debate

In May 2022 the BrooklynSpeaks coalition called attention to pending fines, as the project’s Development Agreement seemingly demanded, for developer Greenland’s failure to build the Urban Room. ESD, unwilling to penalize the developer, offered a deflecting quote:

“While the existing plaza in front of the Barclays Center has become an indispensable public space and serves as an important public benefit, ESD acknowledges the importance of ensuring that this developer honors the commitments it promised to the community. ESD will work with the developer and the community to expand access to public space and advance the next phases of this critical project.”

That evaded the question of who controls that public space, and how that came about.

Greenland’s statement was carefully crafted. "We have heard loud and clear from locals, visitors and public officials that Brooklyn's public square is a far better civic space for Brooklyn residents, transit riders, and visitors to Barclays Center than the enclosed atrium originally planned for this site.” it said, pledging “to work with the State and our neighbors to ensure the plaza is protected and that development planned for this site can be re-imagined elsewhere in Pacific Park.”

It wasn’t wrong to say that the plaza likely serves the arena (and the public) better than the smaller Urban Room might have, at least in pleasant weather.

But the statement ignored who controls that space and benefits from it, or that “re-imagining” that development means a potential giant two-tower project at Site 5, as indicated in the graphic below.

At a June 25 meeting of the advisory Atlantic Yards Community Development Corporation (AY CDC), ESD attorney Richard Dorado echoed previous arguments, citing the plaza’s use by protesters. "If you were to plunk a building on that site,” he suggested, “that would be I would think offensive to people who now accept that as an important symbolic site."

Well, if it’s such an important public space, maybe the state should map it as parkland, and have the arena company pay a licensing fee to cordon it off periodically, broadcast advertising, and sell naming rights.

At the AY CDC, debate

Longtime advocacy planner and Pratt academic Ron Shiffman took up my general argument at that AY CDC meeting.

Why not, he suggested, contact Tsai, who also has a philanthropic arm, "and see whether or not they aren't willing to pay something for that land that we are now granting."

Not building the tower, Shiffman observed, would enhance the value of Tsai's properties. Inversely, the as-of-right decision to build that tower, which current master developer Greenland USA could theoretically start without new approvals, would diminish the value to Tsai and Koch.

So, Shiffman said, "why shouldn't we be able to claw back some of [the] financial gain for the public benefit?"

Just transfer the bulk?

Note: the discussion assumed that the plaza would be preserved by transferring the bulk from the unbuilt B1 across Flatbush Avenue to Site 5, longtime home to the big-box stores P.C. Richard and the now-closed Modell’s.

The master developer, Greenland Forest City Partners and now Greenland USA, has since 2015-16 floated plans to move that bulk across Flatbush Avenue, where a 250-foot building had been approved, to create a much larger two-tower project—more than 1.1 million square feet rather than 440,000 square feet.

Some version of that proposal surely will recur, after ESD was encouraged—in a curious motion from AY CDC Chair Daniel Kummer—to ask Greenland for a plan.

Should that be a fait accompli?

Why should a two-tower project with—as proposed in 2016—roughly twice as much bulk as that permitted in the Downtown Brooklyn rezoning be waved through, even if massaged with promises of preserving the plaza, providing other public benefits, and delivering more below-market “affordable housing”?

How big is too big? Does keeping the plaza automatically mean a giant Site 5?

Maybe Greenland could argue that Tsai owes them compensation for not building B1 as of right and not building at Site 5 as large as they’d like.

That said, it’s possible that Prokhorov, agreeing in December 2015 to buy out Forest City’s 55% share in the arena company, got some promise from the master developer—at that point Greenland Forest City Partners—not to build Miss Brooklyn.

If that agreement exists, it was never shared or discussed publicly by ESD. So why should it be viable?

Objection, objection

Responding to Shiffman, AY CDC Chair Daniel Kummer, an attorney, asked, “For clarity, the current owner of the arena and the team do not have rights with respect to the B1 parcel, is that correct?”

“Yes,” responded ESD attorney Dorado.

(Not completely. They didn’t discuss how, while BSE Global doesn’t have rights to the buildable square footage, it’s been ceded rights to the ground-level parcel.)

But they would suffer if it were built, responded Shiffman, suggesting "there is a wedge in here to open up a negotiations with them and get them to think about their kinder angels."

Dorado pushed back, saying that the recent Koch-Tsai transaction "has nothing to do with the real estate at the actual site."

"I understand that there's this idea that if construction doesn't take place on Site 1 that there may be a perceived benefit to the people that use the teams and enterprises that use the arena," Dorado said, "but there's no connection between the two."

No connection?

Whether trumpeted as a centerpiece of Atlantic Yards or denounced as a Trojan Horse aimed to leverage a private upzoning, the arena was always seen as linked to the larger project.

In November 2008, upon Barclays’ recommitment to (and renegotiation of) the arena naming rights deal, original developer Bruce Ratner stated, “Even more importantly, [the arena] is a centerpiece of a development that will bring thousands of jobs and affordable housing units to Brooklyn."

Beyond that, there’s more of a connection than Dorado acknowledged.

As described in the 2009 arena bond prospectus, ESDC would lease the Arena Block Parcel to the Brooklyn Arena Local Development Corporation (BALDC), an affiliate of an ESD alter ego, the state Job Development Authority.

BALDC would sublease the Project Site and the Arena to Brooklyn Events Center, the arena operator, on the condition that the latter ”design, construct, equip, operate and maintain the Arena, the Urban Experience and Subway Entrance.”

The “Urban Experience” = plaza

The Urban Experience was said to be “an interim condition until a so-called Urban Room is developed by AYDC [Atlantic Yards Development Company] or its affiliate or assignee, as required by the Development Agreement between ESDC and the Developer.”

That Urban Experience became the plaza, “a significant public amenity complying with the basic use and design principles of the Urban Room,” no less than 10,000 square feet and “generally open to the public” 24/7.

It would include: landscaping, retail, seating, the new subway entrance, and space to allow for formal and informal public uses. It also could include public art or a prominent sculptural element—like what became the oculus.

But that oculus is also a billboard for advertising, and Tsai added an LED wall over the arena doors, doubling the canvas for promotion. The plaza’s had four sponsors: the Daily News, Resorts World Casino NYC, SeatGeek, and, most recently, Ticketmaster.

Even the “You Belong Here”/”We Belong Here” neon signage installed over the transit entrance serves both as art and advertising, as I wrote for The Indypendent in December 2021.

Not supposed to be permanent

The plaza wasn’t expected to be permanent. Consider the Amended Memorandum of Environmental Commitments, part of the 2010 Development Agreement, the contract between ESD and the developer:

The urban plaza shall be completed and available for public use upon the date of the opening of the arena. Thereafter, [developer Forest City] shall operate and maintain the urban plaza in good and clean condition, until such time as the area occupied by the urban plaza is required for construction of Building 1 or the Urban Room.

That’s repeated in a 2014 update to the document, a Second Amended Memorandum of Environmental Commitments, before the Prokhorov takeover.

There’s been no update to acknowledge the divergence of interest, and ownership, between the project’s master developer and the arena operator.

What if they build B1?

The 2009 bond prospectus presumed a scenario for building the flagship tower, and converting the plaza into an atrium:

B-1 Occupant shall notify the Arena Parcel Occupant when it is ready to proceed with the construction of Building B-1 and/or the modification of the public amenity comprising a plaza and other facilities in the portion of the Arena Parcel adjacent to Flatbush and Atlantic Avenues (the “Urban Experience”) into the permanent glass-enclosed urban room… (the “Urban Room”), such notice shall indicate in reasonable detail the planned construction activities and the portion of the Arena Parcel that will be affected thereby.

Back then, the B1 Occupant and the Arena Parcel Occupant were affiliates. Not any more.

But who would control the signage and advertising on the Urban Room and B1? When the arena operator and master developer were affiliated, that wasn’t much of an issue. Now, it would be.

What if the master developer wants revenue-producing signage at Site 5? Coupled with promotional space at the arena, that might more than double the once-contemplated advertising signage at that intersection.

The other gifts

If Tsai and Koch get to keep the plaza, it wouldn’t be the first public giveaways to the arena operating company.

After all the company doesn’t pay taxes—foregone property taxes this past fiscal year reached $110.2 million—but instead makes payments in lieu of taxes, or PILOTs, to cover construction debt.

Also, BSE Global gets a lower interest rate from tax-exempt bonds. The original bond issuance would have saved perhaps $150 million over taxable bonds.

A later refinancing, at a lower interest rate, saved even more, as indicated by the Aug. 16, 2015 Bloomberg headline below, referring to Mikhail Prokhorov, who in late 2015 succeeded Forest City Ratner as principal owner of the arena company.

So public resources and assistance—including direct subsidies and other tax breaks—bolstered the arena. (Again, consider opportunity costs and more.)

In the Tsai-Koch transaction, the arena was said to be valued at $1.5 billion, far more than the valuation in the Prokhorov-Tsai transaction, and surely aimed at the future, rather calculated as a multiple of current revenue.

Yes, the Barclays Center has not made a profit in recent years, though it’s on track to do better this year. But the arena, as I’ve argued, is crucial to the skyrocketing valuation of the team and overall BSE Global package.

And the plaza, ceded by public agencies representing the public interest, is clearly part of that.