Was Atlantic Yards Fundamentally Flawed?

Yes, a cascade of problems impeded progress. At the start, though, Dan Doctoroff thought it "a crazy risk" (but didn't say so).

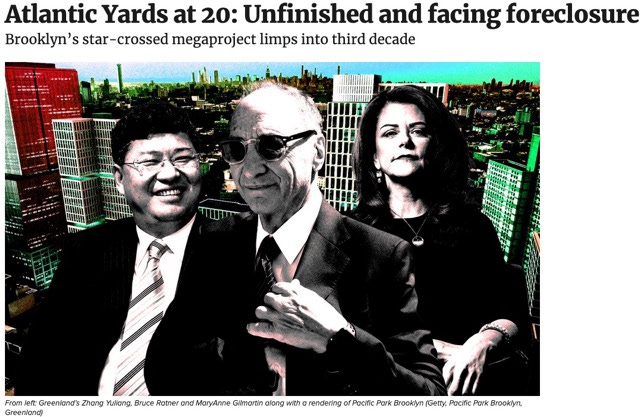

Last week’s article in The Real Deal, Atlantic Yards at 20: Unfinished and facing foreclosure, offered a useful but incomplete summation of factors—including economic and political cycles— hampering the megaproject announced in 2003 by Brooklyn-based Forest City Ratner, with a projected ten-year buildout.

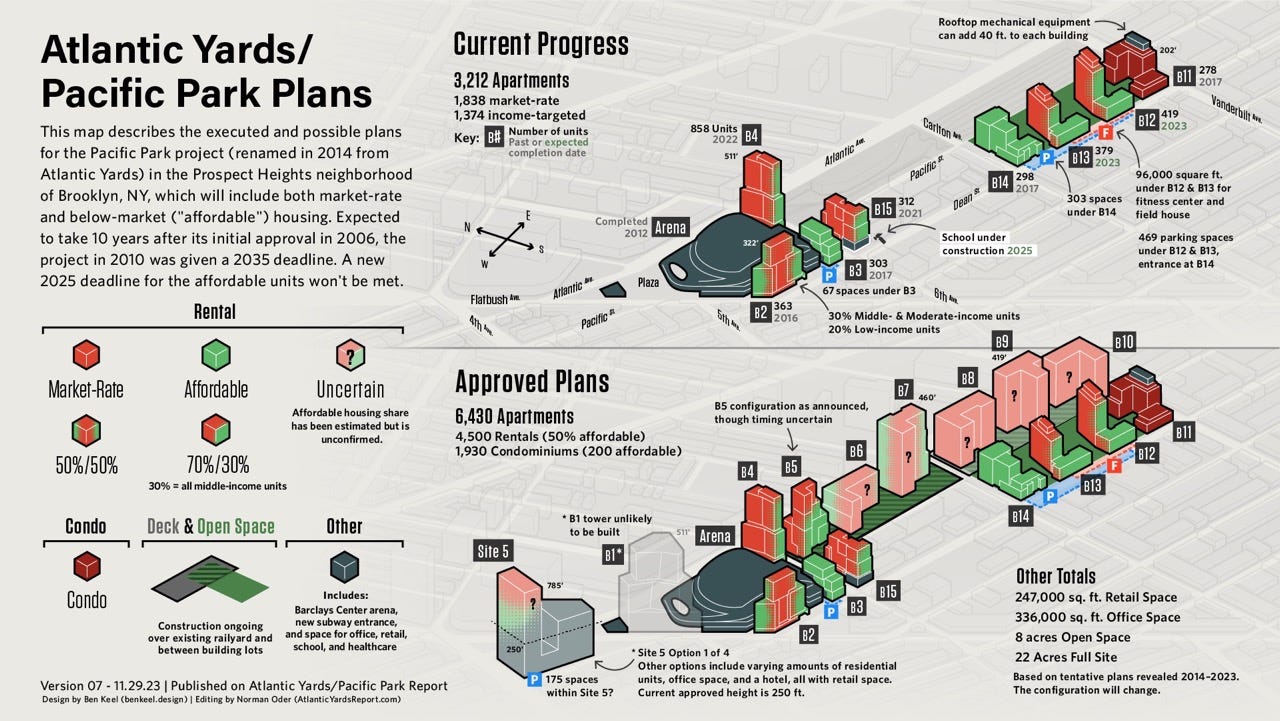

The lack of revenue means that the current master developer, Greenland USA, owes about $286 million loaned by immigrant investors under the EB-5 program, and faces a foreclosure auction Jan. 11 [update: oft-postponed] of the rights to six development sites over the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s Vanderbilt Yard.

But the article missed some things, notably a fundamental flaw in the project, as suggested by former Deputy Mayor Dan Doctoroff in his 2017 memoir, Greater Than Ever: New York’s Big Comeback.

A “crazy risk”

Around 2003, when developer Bruce Ratner was conceiving the project, he faced big challenges, Doctoroff wrote.

Ratner had to:

buy the New Jersey Nets to move them to Brooklyn;

reach an agreement with New York State’s Empire State Development Corporation (aka Empire State Development) for the overall project

negotiate with the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) to gain development rights and manage work at and around the Vanderbilt Yard; and

make progress while absorbing losses on the Nets, as the Jersey fan base faded.

“I thought it was a crazy risk, but hey, it was his money,” recalled Doctoroff. Not that he said so. “My role in this,” he wrote, “was to be as supportive and reassuring as possible.”

That extended to direct and indirect subsidies, as well as muscling the MTA on Ratner’s behalf.

Thanks in part to such public support and unrealistic economic predictions from official and unofficial sources, a lot of people, including opponents and critics (like me) of the project, expected Ratner would reap riches.

Heck, in an August 2006 New York cover story skeptical of Ratner’s plan, “real-estate expert Jeffrey Jackson”—an appraiser, not a megaproject analyst—concluded that “ Ratner should make around $700 million to $1 billion—about a 25 percent return. That’s pretty good.”

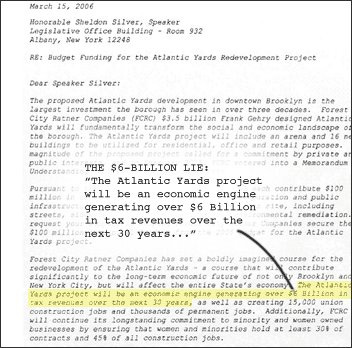

In March 2006, I critiqued the promotional study, by paid Ratner consultant Andrew Zimbalist, that the project would deliver $6 billion in new tax revenues over 30 years. But I didn’t extrapolate that such unwise assumptions also imperiled the project.

Atlantic Yards still was, I’d contend, a wired deal that delivered benefits to a preferred developer and ignored alternatives. I’ve called it the Culture of Cheating.

And because it was a wired deal, it escaped crucial scrutiny, not just of the overblown public benefits but also of the ability of the developer to reach its goals.

“So, is Atlantic Yards a boondoggle or a house of cards?” the New York Observer’s Matthew Scheurman mused presciently in July 2007. “It could, perhaps, be both.”

The public sector’s role

Contra Doctoroff, it wasn’t just “his money,” or from Ratner’s parent company Forest City Enterprises, though they wound up investing, and losing, a lot.

Rather, the public-private project—or, as I’ve put it, “private-public project”—received a significant amount of city, state, and even federal support. It benefited by the state exercise of eminent domain. It was hardly as-of-right.

That argued for more rigorous oversight, in terms of both estimating benefits and assessing risks, which might have led to a different, more buildable project.

Instead, public officials repeated best-case scenarios, based on an unrealistic ten-year buildout, then later relaxed requirements.

The MTA agreed to let payment for railyard development rights be extended through 2030. Empire State Development allowed eminent domain in stages and a 2035 project completion date.

What now?

Today that means that the MTA’s two-block, below-grade railyard, a purportedly “blighting” influence, remains uncovered. (The Barclays Center arena was built partly in the bed of one railyard block.)

Six towers have been approved, though they depend on an expensive platform, a change in state tax subsidies, and, perhaps, a new developer.

Only completion of those towers would bring five additional acres of open space and the heart of “Pacific Park,” in the eastern half of the image below.

It’s hardly clear that anyone will bid on those sites Jan. 11, at least until we learn whether a May 2025 deadline for affordable housing, with 876 apartments to go and $2,000/month fines for each missing unit, transfers to the new owner. (Stay tuned for more on that.)

Recognizing complexity

That timeline never seemed realistic. But it took longer for many to recognize the risks inherent in a multi-part project subject to economic, political, and ownership cycles, with multiple government agencies playing a role.

Discussing Atlantic Yards at a 2012 panel before the arena opened, Marilyn Taylor, then Dean of the University of Pennsylvania's School of Design, offered some sage advice:

"I think any project like this can only be successful if the public goes through a sometimes lengthy process to say, 'What are our objectives on this site and how much are we, the public sector, willing to invest…?' And then the developer needs to be able to respond, not within tight limitations, but within that framework and yet still able to have that flexibility to meet what the market delivers."

That would’ve been a useful tactic in 2003 and even by 2012, since it might have averted the current crisis.

Multiple factors

What went wrong, according to the Real Deal:

Local opposition and lawsuits caused years of delays, and then the Financial Crisis hit. An attempt at modular construction went awry. Forest City Ratner dissolved, Greenland ran into headwinds in China, the pandemic came and interest rates soared.

Sure, but shouldn’t Ratner and his government backers have assumed that a giant project presented as a fait accompli, encroaching on some gentrified/gentrifying neighborhoods, would’ve generated some pushback?

(I’ll grant that the Internet-based opposition was something new.)

Didn’t they know—based, for example, on the history of Ratner’s MetroTech development in Brooklyn—that financial cycles affect any lengthy project?

Note: Ratner’s firm wasn’t just attempting modular construction. They aimed to build all 15-16 towers using off-site methods, cutting time and cost, leading to a new business line.

It didn’t work, as I explained for City Limits. But if it had, maybe Ratner’s “crazy risk” would’ve paid off and we wouldn’t be here today.

Yes, Greenland ran into headwinds in China, but the risks of big real-estate companies seeking to expand aggressively should have been anticipated.

Local advocate Gib Veconi, a leader of the BrooklynSpeaks coalition, argued in 2014 that the site should be split up among multiple developers.

Like Forest City Ratner’s project, the emerging deal with Greenland USA, he warned, represented another single-source development project, "but under the control of a partner exposed to one of the world's most volatile economies."

About that partner

The Real Deal added to our understanding by quoting former Deputy Mayor Alicia Glen, who, in a visit to Shanghai, found the Greenland Group, parent of the new majority owner, notably focused on the project’s condos, not the affordable rentals it was obliged to build.

If Glen was alarmed, as of her late-2015 visit to meet with Greenland Chairman Zhang Yuliang, well, she should’ve been warned. In late 2013, Zhang told reporters that Atlantic Yards would take just eight years to finish.

(Forest City, according to the Wall Street Journal, declined to comment, likely unwilling to contradict their incoming partner and jeopardize the pending deal.)

I observed that either something was lost in the translation, and/or Zhang had become afflicted with the kind of timeline hyperbole previously practiced by Bruce Ratner and his deputy Jim Stuckey.

Bad luck

I’d add that Greenland surely didn’t anticipate the expiration of the provision in the 421-a tax break that applied to condos, nor the later expiration of 421-a as it applied to rentals. (It may come back.)

Perhaps developers in China that rely significantly on government ownership expect more predictability?

Public commitments

To the Real Deal, former Forest City CEO MaryAnne Gilmartin also recalled that Forest City made costly public commitments.

I’d identify them as moving the MTA’s Vanderbilt Yard, used to store and service Long Island Rail Road trains; building a new subway entrance that connect to the Barclays Center plaza and significantly helps the arena; and pledging to buy development rights over the railyard.

Then again, Forest City were able to renegotiate the MTA deal, with the gubernatorially controlled state authority the developer to pay $20 million for the parcel needed for (part of) the arena and pay the rest of its $100 million pledge over 22 years, at a gentle interest rate.

That came three years after the MTA decided to negotiate solely with Forest City, which had bid $50 million cash, while another developer, Extell, bid $150 million. Forest City said the bids weren’t comparable. We never got a chance to find out.

Timing questions

“We front-loaded a lot of the equity, and it didn’t produce revenue and a return for a very, very long time,” Gilmartin told the publication.

That was a miscalculation. When Forest City and partners had invested $250 million in Atlantic Yards, above and beyond the Nets, that was the largest single investment the company had made, an official told investors in October 2007, declaring it "risk-appropriate."

So let's recall an article I wrote in March 2007, quoting affordable housing analyst David Smith. Forest City Ratner had already invested $230 million, less than half of the $550 million or ultimately invested in the project.

"The $230 million of capital already invested is a jaw-dropping sum, especially since we are four years into the transaction and it has not closed,” Smith observed at the time.

“Very few entities could put up that much capital for that long,” he added. “Setting aside whether one likes or dislikes the process or the property, no one should underestimate how few sponsors could attempt it, nor how many fewer would attempt it.”

Smith called the lag between first outflow of capital, in 2004, to net inflow, at that point predicted in 2013, a dramatic one. “A tremendous amount is riding on expected residual value in a decade,” he said in 2007. “I cannot imagine the developer will not have tried to lay a large portion of that off on outside capital sources."

That, indeed is what happened, first with Greenland and then with the EB-5 investors.

“Hard lessons”

Again, Forest City miscalculated. In December 2013, David LaRue, CEO of the Cleveland-based parent company, acknowledged two “hard lessons we’ve learned coming out of the recession. We need to control land rather than own it, prior to being ready to go vertical, and we need a strong capital partner up front for a project of this magnitude.”

Is that another way for saying the project was fundamentally flawed?

At what point should Ratner have turned away? “They’re swinging for the fences with these big, mixed-use projects,” Paul Adornato, a veteran real-estate analyst, observed of Forest City in 2018. “They take many years and are very complex. They’re either going to be a home run or a whiff.”

A mixed legacy

From a financial perspective, for Ratner and for Greenland, it’s been a whiff. (For others, it hasn’t. Stay tuned for more on that.)

Has Atlantic Yards been good for Brooklyn and the city?

Doctoroff, as of 2017, suggested that the positive reception to the arena, the presence of two professional teams (oops—the New York Islanders left), and rising property values nearby all vindicated the decision. In her public speeches and Real Deal interview, Gilmartin has spoken similarly.

Then again, Doctoroff also wrote that “thousands of units of desperately needed affordable housing are finally coming online,” without noticing the skew toward middle-income units, some renting for $3,700.

(Nor did he anticipate that the 2025 deadline wouldn’t be met.)

Doctoroff acknowledged that "I don't think we will ever know" whether Ratner would make money—now, we do know—but wrote that the developer's "vision, commitment, and tenacity made the transformative project possible."‘

Except the railyard remains, the open space awaits, and the affordability is ever attenuated. So expect more debate about the project and its legacy.

A victim of its own success?

Was Atlantic Yards, as the Real Deal article suggests, a "victim of its own success"? Well, only in part, as I wrote, as developments nearby moved faster, given the lack of complicated infrastructure plans and costs.

I think it's more a victim of the Downtown Brooklyn rezoning, which, though assumed to bring new office buildings, instead delivered thousands of new apartments.

That glut led Forest City, in the last phase of its joint venture with Greenland, in 2016 to declare a unilateral pause on the project. A year later, Forest City exited nearly completely, leaving the project in the hands of Greenland and now, apparently, some yet-to-be identified new investors.

What now?

So Dean Taylor’s rhetorical question might recur: “'What are our objectives on this site and how much are we, the public sector, willing to invest?”

After all, if the new bidders don’t build the platform, that expense could fall on the public sector.