Flashback, Dec. 10, 2003: The Atlantic Yards Unveiling

"Bring Basketball to Brooklyn," urged developer Forest City Ratner's web site. The Nets arrived, but many predictions were puffery.

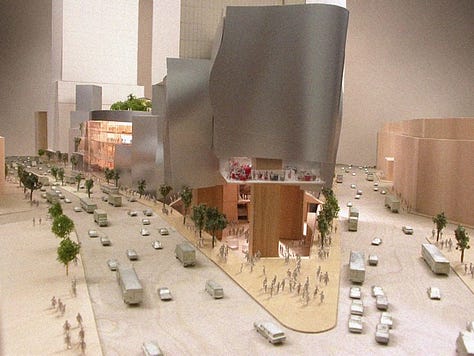

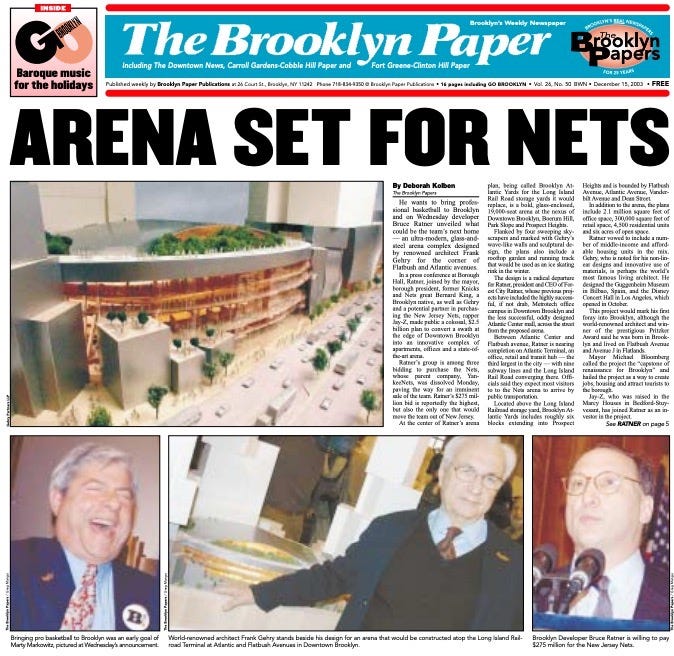

Atlantic Yards was unveiled 20 years ago, on Dec. 10, 2003, at a triumphant press conference at Borough President Marty Markowitz’s Borough Hall. As the Brooklyn Paper put it, publishing a rendering of the (purportedly) publicly accessible green roof, “Arena set for Nets.”

Not quite.

Though “Arena development to begin at the end of 2004, with completion set for the summer of 2006,” according to promotional document, it took nearly nine years. Not only was the 2004 start date unrealistic, lawsuits, the recession, and revision of business terms extended the timeline.

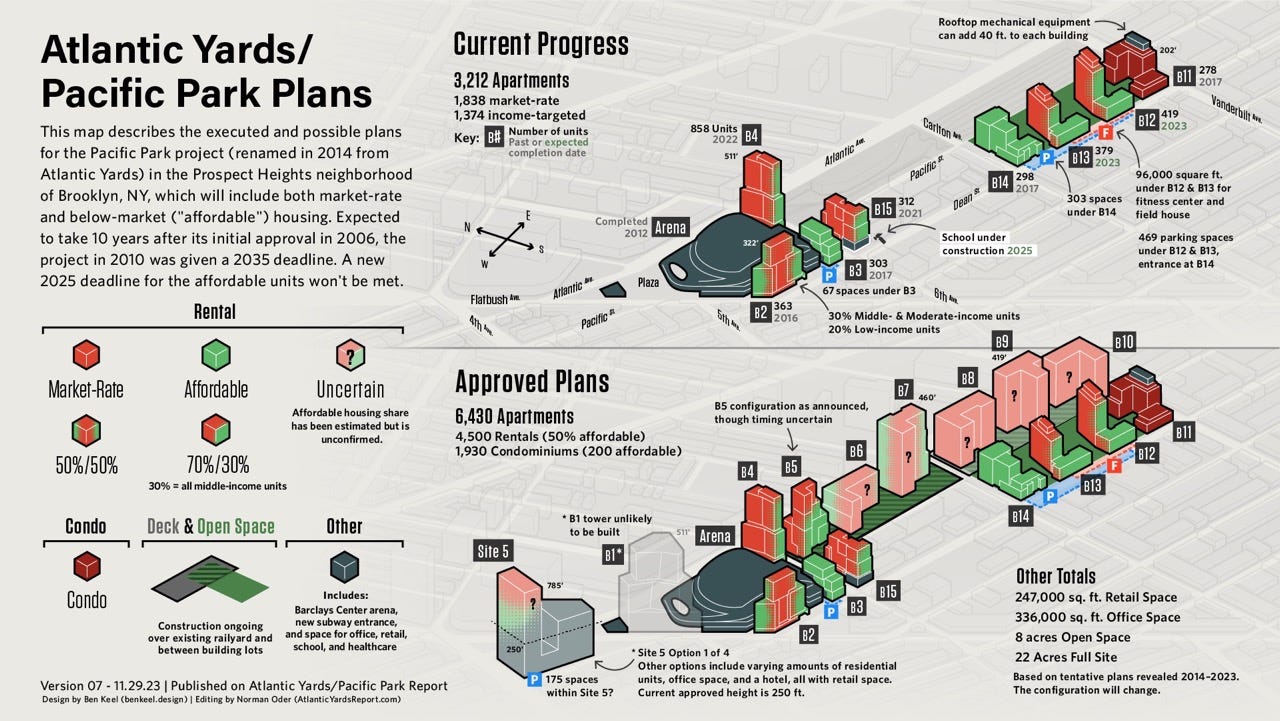

The full project, including an arena and 16 towers, was “estimated” by developer Forest City Ratner to take “approximately 10 years to complete.”

Way off schedule

That, of course, was balderdash. Complex projects can be unsettled by poor conception, economic and political cycles, inadequate oversight, unexpected competition, and reliance on a single developer—or a successor from a country with a real estate industry subject to extreme economic headwinds. This one has all that and more.

(See The Real Deal’s article yesterday, Atlantic Yards at 20: Unfinished and facing foreclosure and my commentary.)

From the promotional copy:

The project has four essential components, which support and complement each other: the Arena, commercial space and housing – interspersed with a significant amount of publicly accessible open space to enhance existing neighborhoods.

Well, the components weren’t equally essential.

Basketball and Brooklyn

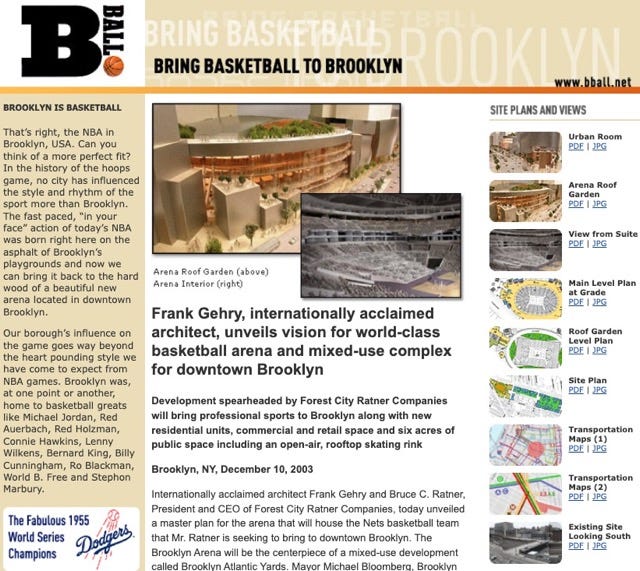

"Bring Basketball to Brooklyn," proclaimed the project’s original website, BBall.net. Only later would the “civic” promises of “Jobs, Housing, and Hoops” be put front and center.

Remember, as of Dec. 10, 2003, veteran Brooklyn real estate developer Bruce Ratner was still pursuing the NBA’s New Jersey Nets, the scarce professional team that would leverage his control over a 22-acre site for a development ultimately approved at 16 towerse and 8 million square feet.

Bringing the Nets and building the arena is, in the eyes of project supporters, the project’s clearest accomplishment: it helped reframe the image of Brooklyn and boosted the value of the team.

The irony: the effort brought riches not to Ratner and his co-investors but to his successor as team owner, Russian oligarch Mikhail Prokhorov, who sold the team and arena company at a huge profit to fellow billionaire Joe Tsai.

From the Dodgers to Gehry

Getting there, as the project website suggested, required invoking Brooklyn’s basketball history and its major league past as home to the Brooklyn Dodgers. (Remember: 20 years ago, far more people, starting with Borough President Markowitz, remembered the Dodgers.)

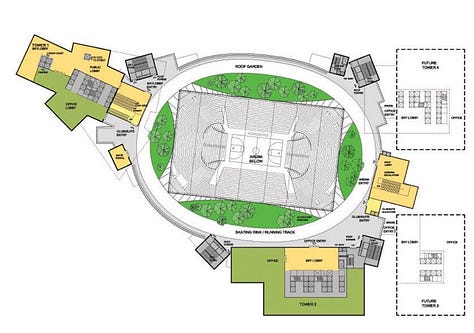

It also cited Brooklyn’s considerable population (“2.5 million would make up America's fourth largest city,” which, yes, was an underserved market) and welcomed “a 20,000 seat, downtown arena designed by an icon of modern architecture, Frank Gehry.”

But it would not be a Gehry arena, nor would a flagship office tower—which Gehry later dubbed “Miss Brooklyn”—rise at the intersection of Atlantic and Flatbush avenues, containing an atrium called an Urban Room.

Note: though that flagship tower was supposed to be “set back slightly… to maintain the view corridor to the Williamsburg Bank building,” that was untenable and, even without “Miss Brooklyn,” the view’s blocked by the smaller B2 tower, 461 Dean.

Nor would the open space be designed by the original landscape architect Laurie Olin. Forest City would exit the project, in stages. And today, with eight of the 15 (or 16) towers completed, the project is less than half-done, and deeply in question.

The project announcement claimed “[t]he complex has been planned to look whole and complete during each phase of construction,” but that was ridiculous. Check out the railyard below, waiting for a platform.

Ironies from the promotional event

The press conference for Brooklyn Atlantic Yards—soon truncated to Atlantic Yards—featured not just Markowitz and Gehry but also Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Brooklyn-born basketball All-Star Bernard King, according to the press release.

Little did they know that King—after a domestic violence arrest—would be disappeared and another Black entertainer present, the not-yet-supernova hip-hop star and entrepreneur Jay-Z, would become far more crucial to the project.

While Forest City then emphasized “Downtown Brooklyn”—associating the sought-after scale with downtown density—today the arena block marks a transition zone from Downtown Brooklyn to the Prospect Heights neighborhood.

With Downtown Brooklyn built up far beyond anyone envisioned in 2003, thanks to the Downtown Brooklyn rezoning (which I’ll address separately), the developers of the newest Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park buildings now proudly claim “Prospect Heights.”

An aspirational gallery

Some of the most notable images in the 2003 gallery below were chimerical. For example, there’d be no access to the roof.

That “Urban Room” was never delivered, given the failure to build “Miss Brooklyn,” and a “temporary” plaza, crucial to arena operations, emerged instead.

The skyline doesn’t exist, and the eight towers completed so far, of 15 (or 16), form only a component of Brooklyn’s new skyline. Most of the largest towers await. So Gehry could not, as he aimed, “create something really special for Brooklyn.”

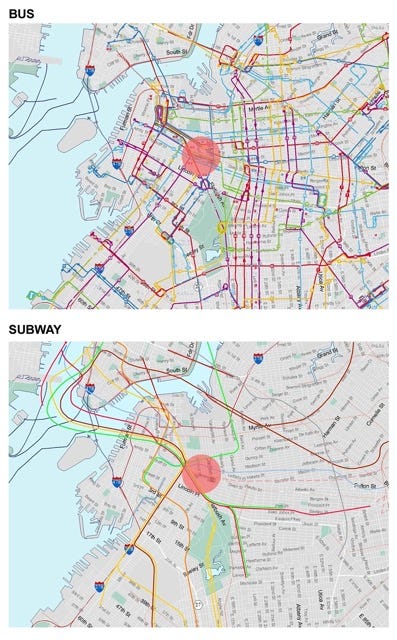

Ratner wasn’t completely wrong that the Nets—at least in some years—would be “a huge draw for sports fans.” After all, as maps indicate, the location near Atlantic Terminal offered significant subway (and bus) access, while—a crucial but less stressed element at the time—offering a short trip to high rollers on Wall Street.

And the accidental, “temporary” plaza has become crucial to arena operations.

“Projects change, markets change”

Let’s recall a laconic comment, delivered less than two years after the launch, by Forest City executive Jim Stuckey: “Projects change, markets change.” That was an understatement.

The arena would not be 800,000 square-feet. Nor would it be designed by Gehry. It was downsized in the Great Recession, with an adaptation of Ellerbe Becket’s Indianapolis arena rescued by the firm SHoP’s new skin and oculus.

There’d be no 2.1 million square feet of commercial office space. Of the four promised office towers, three were traded for housing and the “Miss Brooklyn” wasn’t built. So much for 10,000 office jobs.

There wouldn’t be 4,500 housing units but rather 4,500 rental apartments and 1,930 condos—at least as approved.

The “park on the Arena’s roof, ringed by an open-air running track that doubles as a skating rink in winter,” was not to be. Atlantic Avenue would not be transformed into a tree-lined boulevard.

While the initially promised six acres of open space would later be increased to eight acres, only three acres, in 20 years, have been delivered. The rest relies on a costly platform over the MTA’s Vanderbilt Yard.

There wouldn’t be 4,500 apartments but rather 6,430, with about half built so far. However, the slow buildout has meant that the fraction of below-market “affordable” units have been far more costly than initially promised.

There wouldn’t be 3,000 parking spaces—instead, far fewer. That’s saved the developers money and incentivized public transit, though heavy demand for parking during certain arena events means traffic jams and illegal parking and idling.

The abdication of skepticism

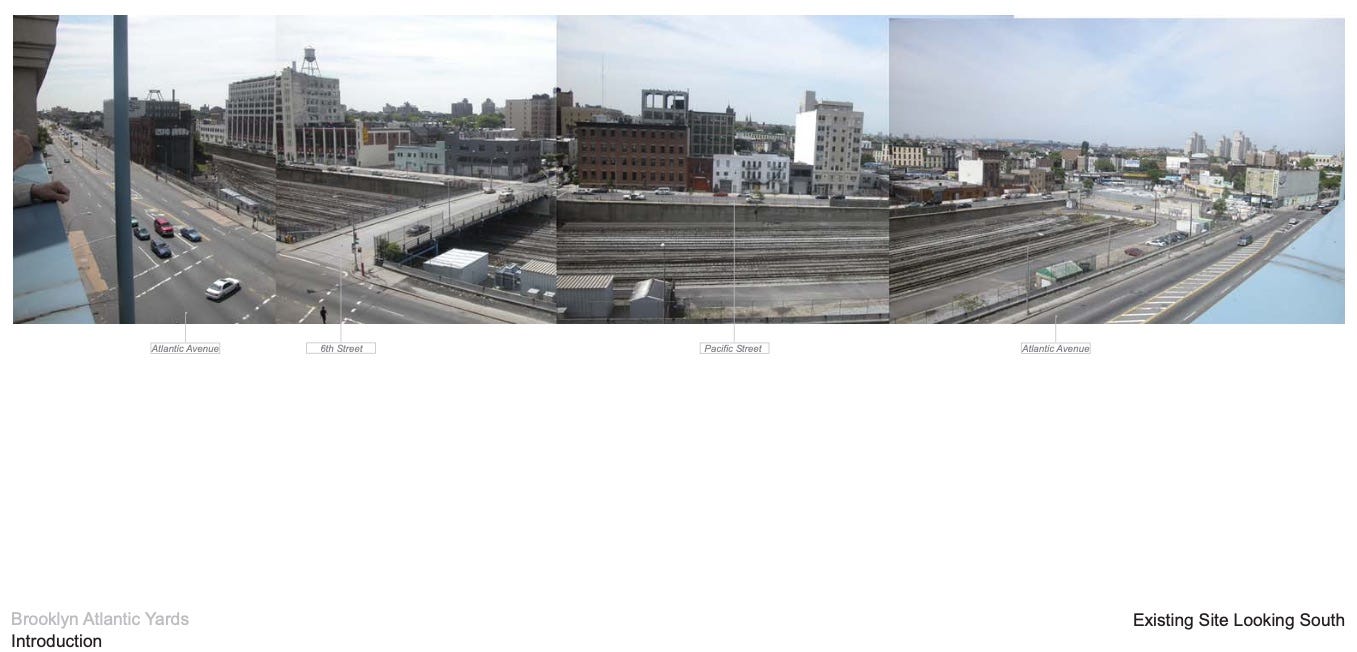

When Mayor Bloomberg signed on to support Atlantic Yards, that signaled an abdication of skepticism by government leaders. Consider the montage below, presented as “Existing Site Looking South.”

The fisheye lens, combining three photos looking south from Atlantic Avenue, leaves the impression that the site consisted mainly of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s Vanderbilt Yard, used to store and service Long Island Rail Road trains. But the railyard, at 8.5 acres, represented less than 40% of the 22-acre site.

In fact, the left-most image in the montage above, stretches east from Sixth Avenue (not 6th Street, as the caption says) to Carlton Avenue, leaving no image of another block, from Carlton Avenue to Vanderbilt Avenue. The right-most image, by the way, includes the segment of the railyard in which perhaps half of the arena was built.

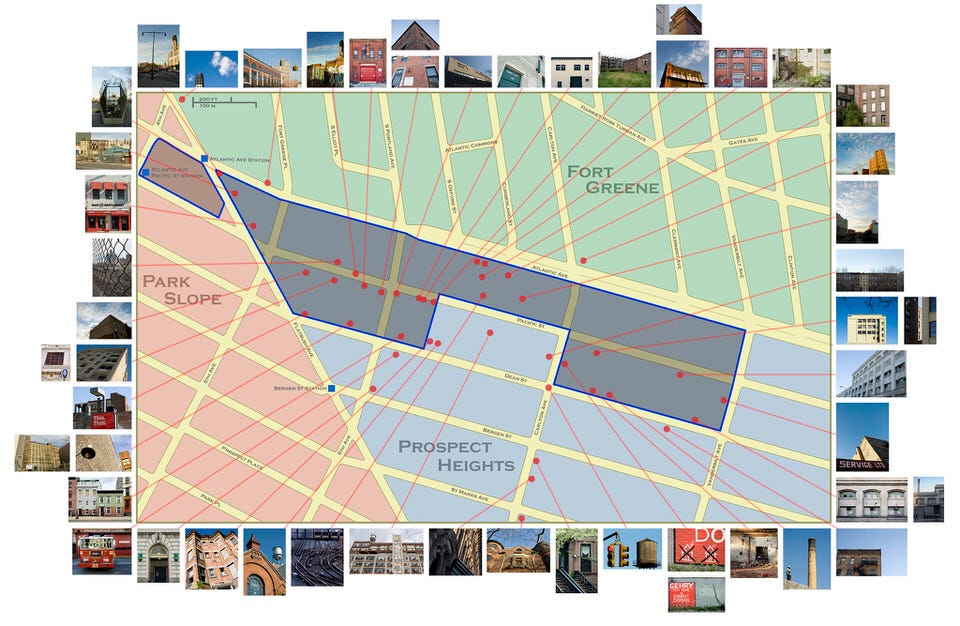

So that ignores the blocks needed for the project and their neighbors, as captured in this photo map from Tracy Collins. No, it wasn’t a pristine brownstone neighborhood. But it was a neighborhood with assets, including recently renovated former industrial buildings, and others pending rehab.

In 2014, when Greenland USA—an arm of Shanghai-based Greenland Holdings Corp.—bought 70% of the project (excepting the arena company and the B2 tower, 461 Dean St.) from Forest City, it changed the project’s name to Pacific Park Brooklyn. That, I argued, was to gain distance from the development’s taint.

How changes emerged

Atlantic Yards did in some ways evolve in response to criticism. In the site plan below, the buildings, as initially designed, walled off the open space on the eastern superblock, but later were separated to allow more corridors.

But so many of the changes in the project, rather, would be driven by bottom-line realities. To quote (partly) from a Carol Willis title, “Form Follows Finance.”

A fig leaf on process

The below paragraph rather cursorily addressed the complicated—and, as it turned out—contentious public process regarding the project.

The Brooklyn Atlantic Yards will be developed as a general project plan of the State’s ESDC, which is subject to environmental review under the State’s Environmental Quality Review Act (SEQRA). This review will include public hearings and community participation. The developer, Forest City Ratner Companies, has a long history of working cooperatively with Brooklyn’s civic, business and community leaders – as evidenced throughout the 15-year development of MetroTech Center – and will continue to do so on this important project.

Yes, there would be public hearings and community participation. But there was, at this point, no mention of eminent domain, the state power to take private property for public use (redefined as “public purpose”), and the justification for eminent domain, the site’s alleged blighted nature.

The location

From the promotional copy:

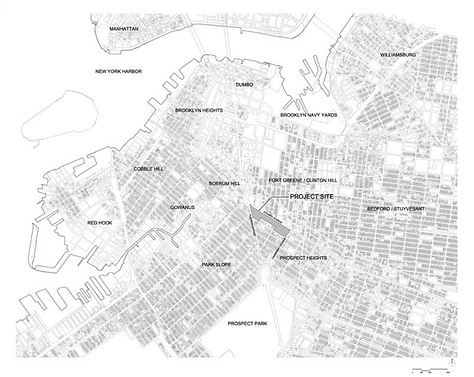

Generally bounded by Flatbush Avenue, Atlantic Avenue, Vanderbilt Avenue and Dean Street, the project consists of six blocks of varying size. The site – approximately halfway between the Brooklyn Bridge and Prospect Park – sits between the Brooklyn Academy of Music and the neighborhoods of Fort Greene, Prospect Heights, Park Slope and Boerum Hill.

That’s not actually true. Most of the project site is clearly in Prospect Heights, with Site 5—unmentioned at the time—across Flatbush Avenue and technically in Park Slope. Site 5 and the arena site could be argued to extend Downtown Brooklyn.

Another claim:

The Brooklyn Arena will sit on a three-block parcel of land at the intersection of Flatbush and Atlantic Avenues – the same area where Walter O’Malley, the legendary owner of baseball’s Brooklyn Dodgers, had envisioned a home for his team nearly half a century ago.

That’s not incorrect, but “area” is not the same as “site,” a common error.

The Brooklyn future

One goal of the project was to “respect the scale of the existing neighborhoods surrounding the site,” which—as some objected—would also change the existing blocks on the site.

Since then, as I’ll write, the existing neighborhoods changed as well.

The proponents contended:

Creating a node of higher density around the transportation hub at Atlantic Terminal will allow Brooklyn to grow while preserving the character of its already developed neighborhoods.

Well, that was 20 years ago. The nodes of higher density have increased in multiple places, not just near the transit hub but in Downtown Brooklyn, along Atlantic Avenue, and on Fourth Avenue.

Of course, the biggest tower, B1 in the map below, was never built. But no real estate developer discards unbuilt square footage. So a giant project at Site 5, the next closest site to the transit hub, may still await.

Thanks for doing this. I wondered what your thoughts were these days!