"Jobs, Housing & Hoops"? Tallying Key Atlantic Yards Promises and Realities

Yes, they built an arena for sports and events. (Biggest winners: two billionaires.) Promised social benefit and neighborhood connection have fallen far short.

The showing Feb. 28 of the documentary Battle for Brooklyn prompted questions about how to assess the project’s promises. Some I’d almost forgotten. They don’t have equal weight, of course.

So, how should Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park be assessed? Some people, like former Deputy Mayor Dan Doctoroff, salute the transformative change at the key crossroads of Flatbush and Atlantic avenues, with a striking arena lauded by architecture critics.

After all, the Barclays Center has enabled the return of major league sports, via the Brooklyn Nets, and hosts major concerts and family shows—though fewer than the promised numbers. It has helped rebrand Brooklyn.

The end justifies the means, including sketchy eminent domain and significant subsidies and tax breaks. That’s all helped the owners of the Nets and the arena company—not original developer Bruce Ratner, as suggested in the documentary, but successors (Russian oligarch) Mikhail Prokhorov and (Alibaba billionaire) Joe Tsai—make huge profits.

(Why arena company? Because the arena itself is nominally state owned, allowing for a tax-exempt site and tax-exempt financing. ArenaCo pays off construction debt with PILOTs, or payments in lieu of taxes. A nice deal—which the Yankees and Mets also got.)

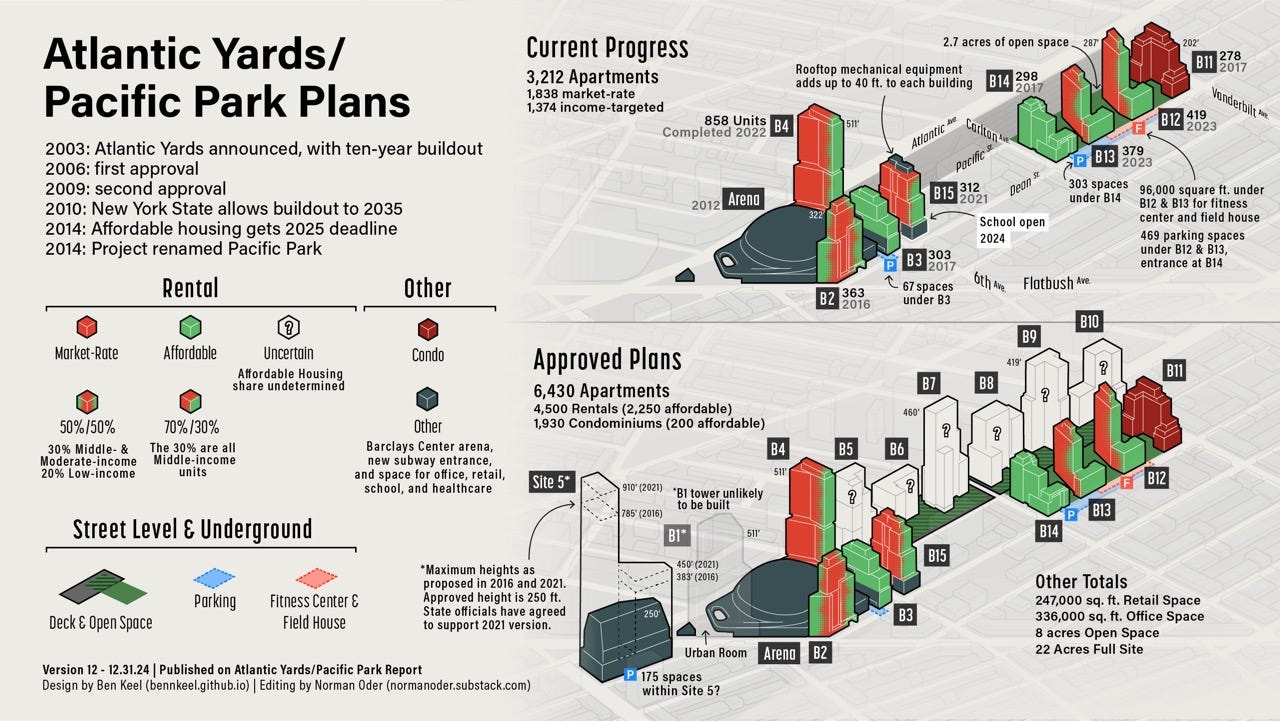

Though the project’s about half-completed, promises of social uplift have been largely not met. Meanwhile, the blocks around the arena complex—absent the railyard blocks—have changed dramatically. (They would’ve changed had an alternative plan proceeded, of course.)

Some restaurant/bar locations are geared, at least in part, to the arena but the overall changes reflect a growing, affluent residential population, thanks to gentrification in the lower-rise neighborhoods and the advent of towers, thanks to rezonings in Downtown Brooklyn and along Fourth Avenue, as well as the eight Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park built so far.

How much of that was the arena? Only some. After all, the public-facing retail on the Atlantic Avenue side of the building failed quickly after Barclays opened in 2012, and spaces on the Flatbush Avenue side didn’t work either, eventually becoming subsumed into a large team store, open noon- 5 pm.

Meanwhile, the goal of knitting together neighborhoods by decking the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s (MTA) Vanderbilt Yard and creating public open space hasn’t been achieved.

Did the arena cause the once-feared carmageddon? No, but arena operations and project construction have regularly encroached on neighbors and the arena relies on a wink-and-a-nod regarding illegal parking and idling on nearby blocks. (More on this another time.)

Big promises

Some remember the extravagant promises (“Jobs, Housing, and Hoops”) of a project that would transform this section of Brooklyn and also stem the impacts of gentrification, which is why the project gained support from organizations representing—or claiming to represent, since most were created for the much-hyped Community Benefits Agreement—working-class Black Brooklynites.

Maybe it was unwise to expect such promises to be upheld. However, the record with affordable housing, job training, construction jobs, and other expected social benefits is far short of the promises.

Note that some promises/projections were public commitments in official governmental documents, while others were in the Atlantic Yards Community Benefits Agreement or developer promotions. Most promises have fallen short; I’ve marked some key ones on the chart in orange. Others remain murky.

Surely the original developer, Forest City Ratner, was disingenuous. They and backers assumed a best-case scenario, rather than the possibility that economic and political cycles—as well as community opposition—would slow the process.

Crucially, New York State approved a project, with a significant amount of direct and indirect assistance, without ensuring that the promises would be met or even assessing the likelihood they’d be met.

(Also see BrooklynSpeaks’ February 2022 tally of project commitments.)

Murky but important numbers

Have 15,000 construction jobs, in job-years, been achieved? Surely not, because the project is about half-finished, with eight towers left. Yes, the arena required more workers, but so would the future infrastructure. Are they at 7,500 jobs? We don’t know.

The 10,000 office jobs, a nice round number, never happened. The plan for four office towers was later downsized to one tower, which hasn’t been built. However, there are permanent jobs in building services and retail.

As of 2012, 105 of the proclaimed 2000-plus arena jobs were said to be full-time; there were said to be 1,240 full-time equivalent jobs. That number was questionable, but presumably, arena-related jobs have increased as BSE Global has expanded.

Important promise: housing

Some promises were more important than others. “Affordable housing” was a huge selling point for the project, especially since it wasn’t required in the Downtown Brooklyn rezoning.

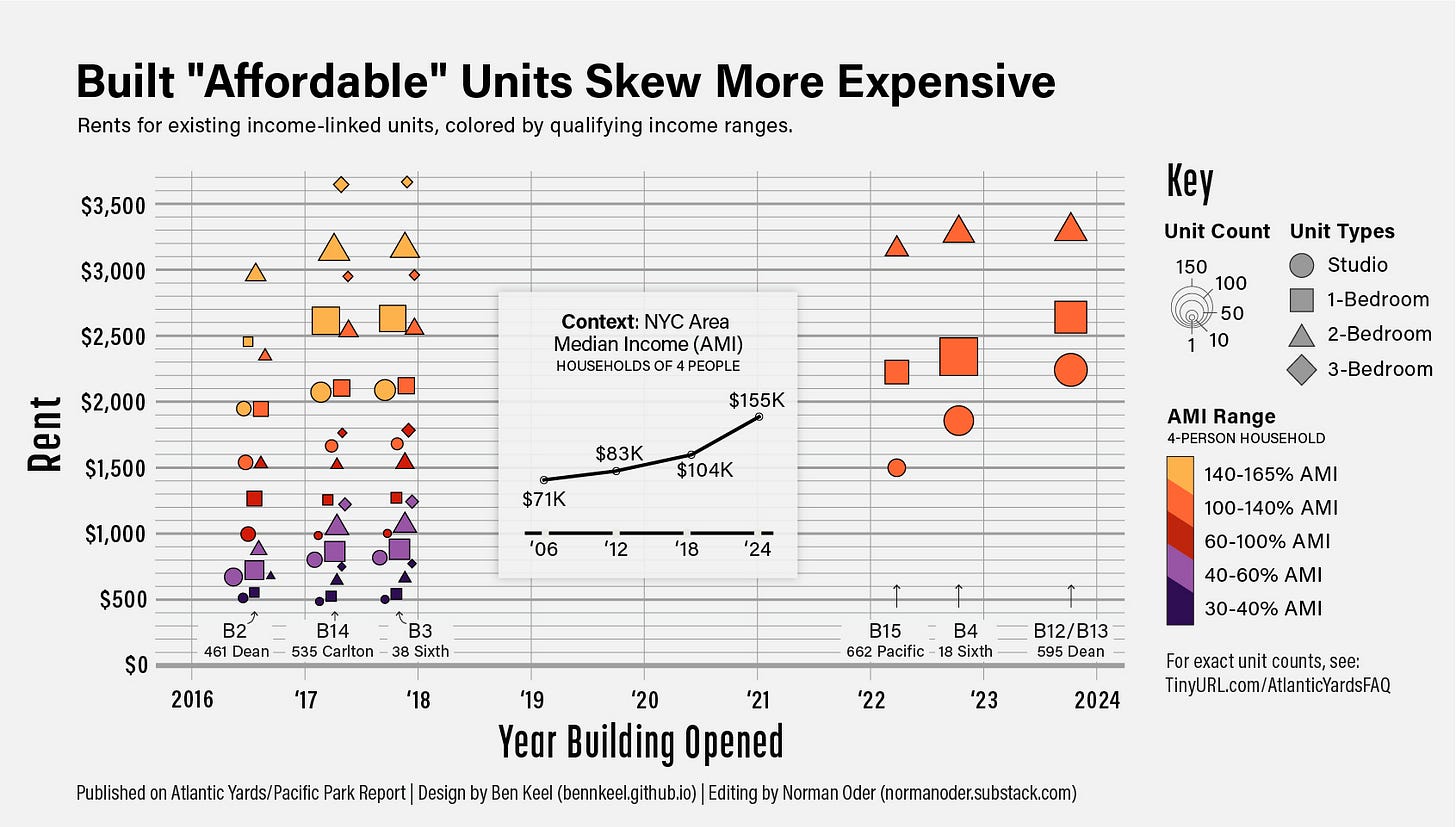

Today, there are 1,374 of 2,250 affordable rentals. That’s 61% complete. Remember, “affordable” just means that tenants pay 30% of their income, so costs can vary considerably.

Here are the promises and current totals, among the five income "bands":

Band 1 (low-income): 225 / 40

Band 2 (low-income): 675 / 214

Band 3 (moderate-income: 450 / 76

Band 4 (middle-income): 450 / 718

Band 5 (middle-income): 450 / 326

The pattern shows a dramatic skew to middle-income apartments, at higher rents. (And those middle-income apartments aren’t necessarily beloved.)

Moreover, as the graphic indicates, the longer the delay, the more expensive housing in each income category becomes.

The remaining 876 affordable housing units face a May 2025 deadline, negotiated in 2014 by the BrooklynSpeaks coalition, which won’t be met. Penalties of $2,000/month for each missing unit are due, but Empire State Development (ESD), the state authority that oversees/shepherds the project, has shown no indication it will enforce that.

As to the affordable condos, Forest City in 2006 claimed it had “already agreed to build 600 to 1,000 affordable home ownership units on- or off-site,” but would “seek to build at least 200 of these … units on site [and] seek to build the remaining … units as close to Atlantic Yards as possible.” Such goals were never locked in.

(Note: when the project was proposed, nobody was arguing—as some do today—that simply any increase in housing supply was worthwhile. Expect that to recur if/when negotiations over the project’s future resume.)

Important promise: job training

The job-training group BUILD (Brooklyn United for Innovative Local Development) launched a coveted pre-apprenticeship training program, aiming to get some people left behind economically into well-paying construction careers.

That program dissolved into a bitter lawsuit, which was settled, with terms undisclosed, after BUILD, in debt, shut down in 2012.

Less important promises

When I suggest the promises below were less important, they weren’t unimportant. They all reflect the unreliability of the project sponsor and the failure of governmental oversight, visible in Battle for Brooklyn, which is being screened Feb. 28.

That’s all part of a process that bypassed the city’s land use procedure, which would’ve given Council Member Letitia James more of a voice, to a gubernatorially controlled state authority which votes as a rubber stamp.

Was it important that the arena be rented at a low cost to community groups ten times a year? Somewhat, but it was more useful for public relations.

State Supreme Court Justice Joan Madden wrote trustingly in January 2008, dismissing a challenge to the environmental reviews, recognizes "that [original developer] Forest City is bound to provide meaningful access to the community for use of the arena." It never happened.

Those 2,000 $15 “screecher seats” to Nets games? That lasted one year, and they weren’t easy to get. A few hundred cropped up in social media promotions, but the rest, a spokesman later said, had been sold to season ticket holders or distributed to community groups.

Was it important that the project would be designed by starchitect Frank Gehry, who prepared the master plan and dramatic, if ultimately unrealistic, renderings? Well, some thought so, though it was more important for public relations.

Gehry had said he’d typically recruit other architects to work with him, so the architectural result so far—some buildings more impressive than others—tracks that pattern. Gehry’s arena was replaced by a pedestrian EllerbeBecket design, which then was rescued by SHoP with a pre-rusted metal mesh.

Was the arena’s green roof, once projected to include a public running and skating track, an important promise? Again, important to public relations. It was value-engineered out. After the arena opened, a new layer of exoskeleton, with green turf, was added, not so much to provide the claimed amenity of views but rather to tamp down escaping bass.

Important (but murky) infrastructure changes

It was important to move and modernize the Vanderbilt Yard functions, storage and service of Long Island Rail Road trains, from the western block, later used for the arena, to the eastern block.

Did the MTA complain about Forest City shrinking the size of that promised railyard to save money? No, it’s a politically controlled state authority.

Is it important to have a new subway exit, paid for by the developer, on the south side of Atlantic Avenue, on what’s now the arena plaza? Sure, that serves the public—but it crucially serves the arena operator.

A promise unmet with better results?

The Urban Room, a public atrium, was supposed to serve B1, the office tower to which it was attached, plus the arena and the transit entrance. Because B1 (which Gehry had dubbed “Miss Brooklyn”) was never built, instead came a “temporary” plaza.

That plaza has been crucial to the arena, allowing places for crowds to gather. It’s also bolstered the arena’s bottom line, with a fourth sponsor, Ticketmaster.

The plaza allows viewing of not just the oculus, the wraparound oval for digital signage, but also a new LED “wall” over the entrance doors and even signage on the exterior of the transit entrance. So it’s become ever more valuable to the arena developer.

When the arena was shuttered in 2020 for the pandemic, the plaza became a locus for public protests in the wake of George Floyd’s killing by a police officer in Minneapolis. Since then, more protests have gathered there, or passed through, though the arena claims the space when needed.

Many see the plaza as a valuable civic space, but it most significant serves the arena.

Today, rather than build B1 (and disrupt arena operations), developer Greenland USA wants to move that unused bulk across Flatbush Avenue to Site 5, the longtime home of the big-box stores P.C. Richard and the now-closed Modell’s, creating a giant two-tower project.

In doing so, the state has been unwilling to enforce the fines on Greenland for not delivering the Urban Room—another benefit.

That would make the plaza permanent. As I’ve argued, I think the arena company owner, BSE Global—owned by Joe Tsai and with a minority share owned by the Koch family—should pay for the privilege.

After all, the project’s big winners are Prokhorov, who made a big profits selling the holding company BSE Global to Tsai, and then Tsai himself, after selling a slice of BSE Global to the Koch family (!) at a hugely increased valuation.

A gold mine for the public?

Atlantic Yards was promised to be a major tax generator, thanks to a spurious study by paid-for economist Andrew Zimbalist, claiming $6 billion in gross revenue and $5 billion in net revenue. City and state studies later predicted significant, albeit more modest, gains.

The NYC Independent Budget Office, by contrast, estimated that the arena would be a loss in terms of city and state tax revenues. (It didn’t examine the whole project. Not did it include the value of naming rights and other benefits.)

No one’s assessed it since. Despite the murk, it’s safe to say that the projected 30-year benefits, assuming completion of the project in ten years, could never be achieved, based on the slow buildout alone, not to mention the suspect methodology.

Looking at the CBA

The Atlantic Yards Atlantic Yards Community Benefits Agreement (CBA), a first-ever contract in New York City between a developer and community groups, was supposed to be legally binding, as stated in the screenshot below, from the Atlantic Yards website on Sept. 6, 2013.

As I wrote last week, certain figures are unclear because there’s been no official reporting.

However, the CBA was supposed to have an Independent Compliance Monitor. That monitor was never hired, I’d bet in part because they didn’t want someone to say they’d fallen short.

Murky results

Among the promises in the screenshot above that remain murky:

hiring priority for public housing residents and low and moderate-income individuals nearby (though there was a job fair for arena jobs)

hiring percentage of minority and women construction workers

MWBE contracting

In 2012, the last time statistics were released, the Atlantic Yards developer was well behind both its own goals and New York State's goals on MWBE contracting.

The CBA, thanks to the influence of the Rev. Herbert Daughtry, leader of the partner group Downtown Brooklyn Neighborhood Alliance (DBNA) was supposed to bring a Meditation Room to the arena, “to be used by the community and patrons.” Well, it exists, but it’s only available to arena staff and ticketholders.

Similarly, the arena developer was supposed to establish a foundation to support local nonprofits. The Atlantic Yards/Nets/DBNA foundation was last active in 2018 but is currently regrouping.

New York State’s stated goals

Quoted below, in italics, are excerpts from New York State’s 2006 Modified General Project Plan. I’ve bolded the sections of my analysis where the goals haven’t been met.

The principal goal of the Atlantic Yards Land Use Improvement and Civic Project is to transform an area that is blighted and underutilized into a vibrant, mixed-use, mixed-income community that capitalizes on the tremendous mass transit service available at this unique location.

As previously reported, the main source of purported blight, the below-grade railyard, still needs a platform. (To be precise, that’s two blocks of the three-block railyard. The third block was used for the parcel containing the arena, which starts below grade.)

The Project aims, through this comprehensive and cohesive plan, to provide for the following public uses and purposes:

• a publicly owned state-of-the-art arena to accommodate the return of a major league sports franchise to Brooklyn while also providing a valuable athletic facility for the City's colleges and local academic institutions, which currently lack adequate athletic facilities, and a new venue for a variety of musical, entertainment, educational, social and civic events;

“Publicly owned” is a fig leaf, enabling tax-exempt financing.

Yes, a major league sports franchise returned to Brooklyn. So did a second one (the NHL’s New York Islanders, briefly, succeeded by the WNBA’s New York Liberty). Some might argue they underpromised and overdelivered regarding major league sports

A valuable athletic facility for colleges and schools? No, it’s hardly been used.

A new venue for a variety of musical, entertainment, educational, social, and civic events? Well, mostly for music and entertainment, not much for educational, social, or civic purposes.

• thousands of critically needed rental housing units for low-, moderate- and middle-income New Yorkers, as well as market-rate rental and condominium units;

As noted, 3,212 (of 6,430 approved) rental housing units, with 1,374 (of 2,250 required “affordable,” but far more middle-income than low-income ones, even as the baseline for calculating affordability keeps rising.

• first-class office space and possibly a hotel to ensure that Downtown Brooklyn can capture its share of future economic growth and new jobs through sustainable, transit-oriented development;

No office space. The market changed. (Note that the developer initially promised 10,000 office jobs, which was later attenuated.) No hotel yet, though one might yet emerge.

• publicly accessible open space that links the surrounding neighborhoods;

Not really. Only 2.7 acres of 8 acres have been completed, and with the railyard yet uncovered, the neighborhoods can’t be linked.

• new ground level retail space to activate the street frontages;

In the main, the new buildings do have ground-level retail. Some retail spaces have taken a while to emerge and the team store flanking the arena, for example, is open for limited hours. The remaining empty spaces, for now, flank the open space.

• community facility spaces, programmed in coordination with local community groups, including a health care center and an intergenerational facility, offering child care as well as youth and senior center services;

There’s a health care center, though there’s no evidence the programming has been coordinated with local community groups or focused on serving low-income people as touted. (The Rev. Daughtry did appear in a photo op.) No intergenerational facility has emerged.

• a state-of-the-art rail storage, cleaning and inspection facility for the LIRR that would enable it to better accommodate, simultaneously, its new fleet of multiple unit series electric propulsion cars operated by LIRR which are compliant with the American with Disabilities Act (the "MU Series Trains") and other transit improvements;

The developer did deliver a new, modern LIRR facility to store and service trains, in the eastern block of the three-block railyard. That said, it was significantly smaller than originally proposed, after being “value engineered” from nine tracks holding 76 cars to seven tracks for 56 cars.

• a subway connection on the south side of Atlantic Avenue at the intersection of Atlantic and Flatbush Avenues, with sufficient capacity to accommodate fans entering or leaving an event at the Arena, eliminating the need for pedestrians approaching the Transportation Hub from the south to cross Atlantic Avenue to enter the subway, and thereby enhancing pedestrian safety;

This has been a significant benefit to those approaching the transit hub from the south, as well as—of course—for arena visitors. Too bad the arena operator can’t keep the escalators working consistently.

• sustainability and green design through the application of comprehensive sustainable design goals that make efficient use of energy, building materials and water; and

As far as I know, this has been achieved, but we haven’t had a full report. That said, such goals are not atypical.

• environmental remediation of the Project Site.

As far as I know, this has been achieved, but we haven’t had a full report. That said, such goals are not atypical.

A CBA reckoning?

In. 2016, as I wrote, a former member of the CBA signatory BUILD criticized Forest City’s failure to deliver.

Self-interest was involved, as Michael West wanted his organization to take over some CBA programs, for a fee. And the video has some errors, as I wrote.

But the sentiment was valid: “Our communities supported them. We lobbied politicians for them," the narrator states. "Held countless community meetings for them. Marched in the streets for them and gave them $1.5 billion of our tax dollars.”

(Direct subsidies, tax breaks, and other benefits exceed hundreds of millions of dollars that I’m not trying to tally at this moment. The arena site, if subject to property tax, would be more than $100 million a year—though that’s the unwise deal other city sports venues have gotten.)

"Why?" the narration continues. "Because Forest City and our politicians signed a contract with our communities promising that we would receive desperately needed job training, construction jobs, construction contracting opportunities, post-construction contracts, retail space for our businesses. Affordable rentals, and affordable home sales."

"Do you see employment increasing in our communities? Do you see our businesses developing? Has the agreement been fulfilled? We say 'no.' We are Devotion," the narration closes. "As community members, we must work together again to assure that Forest City fulfills their commitment."

Other CBA promises

The CBA was so extravagant, with vague goals dependent on others’ funding, that I’ve need to mention some other announced aims:

a High School for Construction Management and Trades plus four other schools

15% of retail space to qualified community-based businesses.

a consortium of lenders to provide low-interest working capital for community-based small businesses (Note that the Social Justice Fund of the Joe and Clara Tsai Foundation has since done its own lending/grants)

work with community-based developers on other development opportunities

MBA Intern Program

office of Arena-Related Programs

annual job fairs

Children’s Zone legislation

In retrospect, one lesson is that, if you don’t consider such agreement truly binding, you can continue to add vague goals that some will embrace as valid.

Great chart, Norman!