Weekly Digest: Sketchy Eminent Domain and a Sketchy CBA Helped Get the Arena Built

A showing of "Battle for Brooklyn" provokes reconsiderations. A huge project in Red Hook reflects another wired deal.

This digest offers a way to keep up with my Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park Report blog and my other coverage in this newsletter and elsewhere.

Welcome new subscribers! You’ll get a weekly (or sometimes bi-weekly) summary of everything I write, usually on a Sunday, so you don’t have to check my long-running blog. You’ll often also get a separate standalone article.

This past week I sent two, about the sketchy history of eminent domain for Atlantic Yards and also the failed promises of the much-hyped Community Benefits Agreement, both reflected in video footage.

This coming week, I’ll send one article but otherwise write less, both here and on the blog. (I’ll be away and will skip the Sunday round-up.)

A movie and its triggers

My unusual pace was triggered a new showing of Battle for Brooklyn, the 2011 documentary about the Atlantic Yards resistance, focusing on Daniel Goldstein—eminent domain plaintiff and Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn spokesman—on Feb. 28 in Red Hook. (There’s a waitlist for tickets.)

Gothamist on Feb. 16 got the exclusive, The Barclays Center's controversial history is revisited at a free event in Red Hook.

As shown by the comments, a good number of people—though Gothamist readers may not be representative—know that the arena and project are tainted by a dubious process and false promises. Some expressed unguarded enthusiasm:

“The stadium was/is an unequivocally good thing for Brooklyn.”

“I am so glad Barclays was built and Brooklyn has been much better because of it.”

Sure, the arena, much lauded by architecture critics and the site of numerous entertaining events, is a big deal, helping rebrand the borough. However, does the (very unfinished) end justify the means?

The big questions left by an unfulfilled project make it hard for me, at least, to think about it unequivocally. Below I share some thoughts about the film, a prelude to a long re-review of the film. (My original review is here.)

Transformative promises

Gothamist quoted me as saying Atlantic Yards has failed “to fulfill [its] transformative promises of jobs and affordable housing.”

“All of the promises were empty,” added film co-director Michael Galinsky. Not quite, because, for example, they did build affordable housing, just less—and less affordably—than promised.

A different context

Watching Battle for Brooklyn in 2025 is different than watching it in 2011. The context is different. The film was released before the Barclays Center opened and eight towers (of 16) built, transforming some nearby blocks and creating a new transit entrance.

That’s more than the “hollow achievement” that New York Times journalist Charles Bagli articulates at the film’s end, but it’s hardly a full achievement. Stay tuned for a separate article on how various project promises stack up.

The focus on the Atlantic Yards resistance, via Goldstein and DDDB, makes for a useful throughline, but the limited attention to gentrification and affordable housing seems more glaring. (The filmmakers narrowed their focus to a few characters, but it can feel too narrow.)

Some elements of the resistance, such as concern about a changed Brooklyn skyline, have been superseded—in part—by rezonings in nearby Downtown Brooklyn and on Fourth Avenue.

However, I suspect few have come to grips with what’s already been approved and the increase likely sought at the Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park site. It would hardly create a “neighborhood,” as original architect Frank Gehry airly claims in the film.

As I wrote last week, the film offers ample evidence for enduring skepticism about the project, in conception and execution.

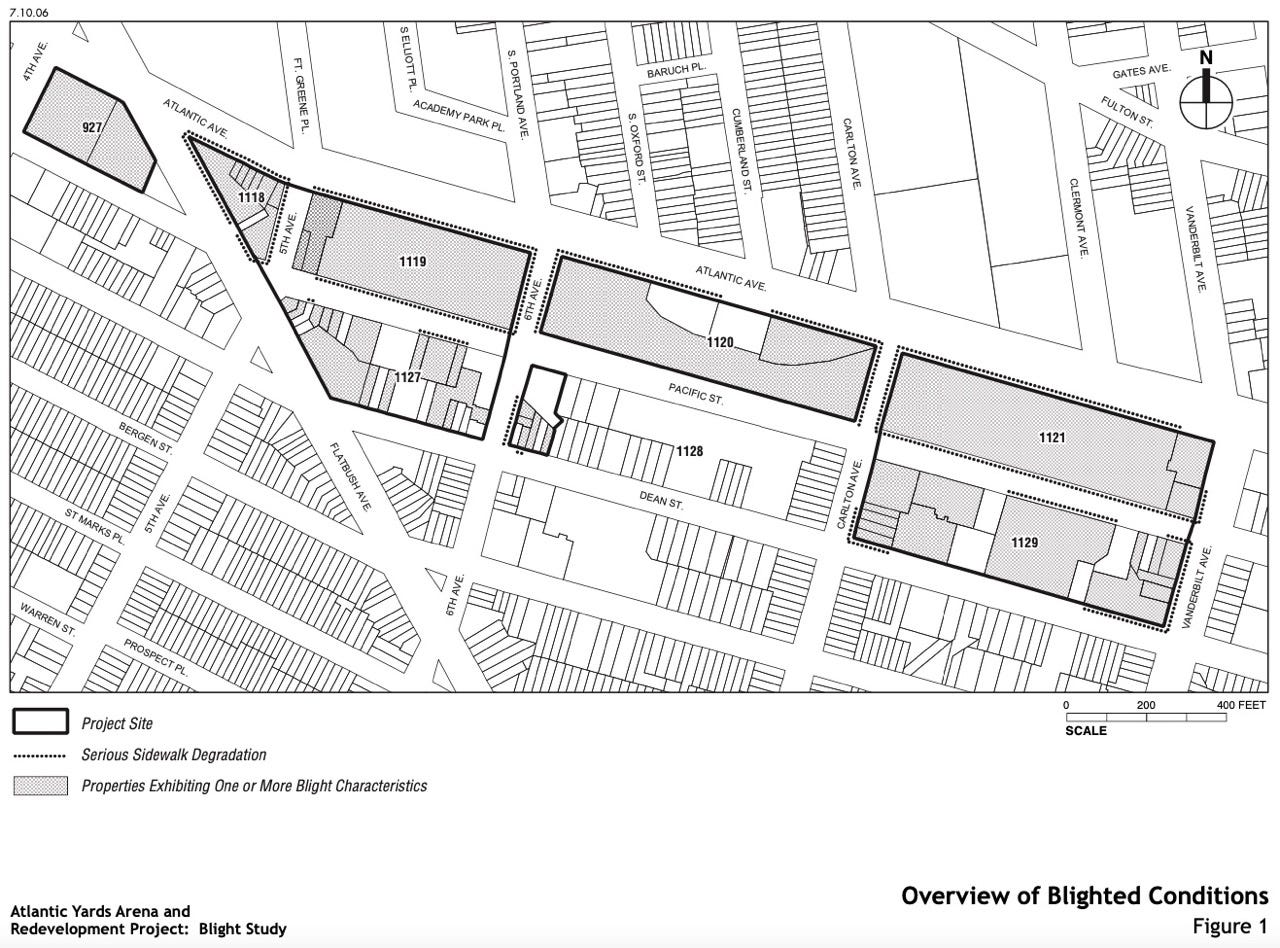

The film’s focus on the wired deal, the willingness of government to accommodate the developers, including the finding of bogus blight and the revision of contracts, is the most enduring legacy.

The skeptical portrayal of the much-touted Community Benefits Agreement, which original developer Forest City Ratner used to recruit support in the working-class Black community, was borne out by the failure of the developer to deliver the jobs and affordable housing promised.

Executives like Bruce Ratner and Jim Stuckey turned out to be just as trustworthy as they sounded in the film.

From this newsletter

Feb. 17: Eminent Domain Reminders from Battle for Brooklyn: Bogus Blight and Dubious Public Use. Did condemnation serve a real "public purpose"? If so, shouldn't the public get a cut of arena/team profits?

As shown in the graphic below, most qualities exhibited “blight characteristics.” However, as Judge Robert Smith skeptically observed, the state’s consultant AKRF “did not find, and it does not appear they could find, that the area where petitioners live is a blighted area.”

After all, weeds, graffiti, and cracks in the sidewalk—all amenable to abatement as a first solution—counted as blight characteristics.

Feb. 20: The Atlantic Yards Independent Compliance Monitor Was Never Hired. The much-hyped Community Benefits Agreement, with promises of jobs, contracting, and housing, was to be accountable. They promised, on video.

Thanks to the directors of Battle for Brooklyn for sharing footage with me.

From Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park Report

Feb. 16: Gothamist's coverage of the new Battle for Brooklyn screening raises some old questions. See more on that further below.

Feb. 18: CNBC: Brooklyn Nets (and arena company) worth $5.6 billion, sixth in NBA. Increase in media rights offers rising tide for all. The investment by the Koch family into BSE Global, owned by Alibaba billionaire Joe Tsai, is key to this elevated valuation.

Feb. 19: A message from the Brooklyn Nets: "we put the city in authenticity." They’ve been claiming authenticity for a while. Tickets are said to start at $47/game, though that price point is hard to get.

Somehow they’re promoting the "Brooklyn Blueprint," encouraging fans to get in on the beginning of something. That’s because the Nets don’t have stars. (They do have some good young players, but how long will they last.)

As seen below, the “blueprint” reflects—does anyone recall?—the odd “blueprint for greatness” promotion when the New Jersey Nets, represented by oligarch owner Mikhail Prokhorov and micro-fractional owner Jay-Z, pursued free agent LeBron James.

Feb. 21: On WBAI's CityWatch, lessons from Atlantic Yards: the need for sober predictions, the cost of delay, the "rational basis" advantage, and the project's big winners. I was interviewed by former Council Member Carlos Menchaca.

Feb. 23: Brooklyn Marine Terminal Plan in Red Hook relies on housing, unspecified until well into "community engagement." Like Atlantic Yards, the project will bypass the city’s land use review, known as ULURP, but with even less legitimacy.

This complicated story has gotten way too little press coverage, but will be discussed at the Battle for Brooklyn screening.

A look at the documents released, as well as those unveiled by community advocates, shows a disturbing pattern: the city downplayed the plan for housing, then it was revealed that 7,000-9,000 housing units were needed to fund the project—and then that figure was increased.

Another reminder from Gothamist

As shown by the comments on the Gothamist article, many people have forgotten—or misheard—basic facts about Atlantic Yards, such as the value of arena naming rights, or the use of modular construction.

Or, for example, the location that Walter O’Malley sought for a new Brooklyn Dodgers stadium. No, it was not the same site as the Barclays Center, but rather nearby.

I’ll write some “explainers” in this newsletter. It’s a complicated project, and it keeps changing.

Gothamist: misreading Goldstein

It was dismaying to see Gothamist, in an article otherwise so sympathetic to the Atlantic Yards resistance that one reader chided it for ignoring the project’s benefits, claim that “Goldstein's obstinance was handsomely rewarded,” since the $3 million he was paid was “quite a raise from the $510,000 the company initially offered him.”

That, as I wrote, lacked clarity and context, as the payment—after he’d already lost his apartment to eminent domain—was to time his departure at Forest City's desire, to ensure that the Nets sale proceeded. Moreover, that $510,000 was a deliberate low-ball, less than what he'd paid originally, as even Gothamist wrote at the time.

No correction or clarification was forthcoming. Sloppy? Malicious? Either way, it was irresponsible.

Gothamist: a bone to pick

In the article, I was described as a "tour guide who maintains a devoted watchdog blog about the development.” Despite the positive valence of the word "devoted," I found the phrasing misleading and demeaning, since it suggests I’m an amateur, rather than a journalist decades before I started my separate tour guide business.

Also, the word "maintains" suggests a passive approach. I suggested Gothamist call me a journalist and use a different verb, like "writes." The response: “Gothamist editors… have decided a correction is not warranted.”

Well, news outlets often get reflexively defensive. The phrasing was, technically, not inaccurate. But it was unwise and unfair, both to me and to readers.