Is 595 Dean a "Successful Project"?

To one real-estate journalist, all looks fine (and supplies fodder to dis Atlantic Yards opponents). But there's more reason for doubt.

“Remember the group Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn?” tweeted the Real Deal’s Erik Engquist recently. “Dean Street between Carlton and Vanderbilt avenues hardly looks destroyed, with a Chelsea Piers Fitness, Simo Pizza, Fujian restaurant, 800 apartments (30% of them affordable) and a 60K-sf public park.”

That linked to his article regarding the two-tower 595 Dean Street (B12 & B13), TF Cornerstone refinances Brooklyn towers with $448M, which began:

Amid all the drama at Pacific Park, the megadevelopment formerly known as Atlantic Yards, TF Cornerstone has quietly put together a successful project at the southeastern end of it — capping it off with a $448 million permanent loan, newly released property records show.

The seven-year, fixed-rate loan from PNC Bank replaces the construction financing for the developer’s 798-unit project at 595 Dean Street, which is fully leased. (TF Cornerstone’s website shows just seven apartments available.) The previous loan came from a consortium of lenders.

Note that perspective matters.

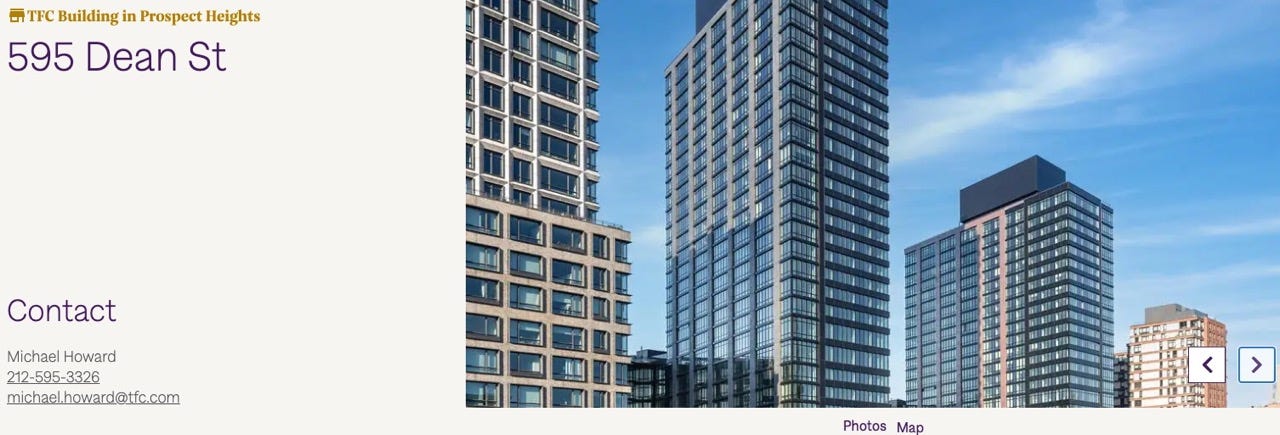

The perspective is far more friendly, with retail at the base, along Dean Street (see further below). while the view from Atlantic Avenue (above), shows the Vanderbilt Yard, site of six future towers and the majority of the future open space.

A successful project?

So, what does a “successful project” mean, beyond the industry sign of approval via a refinancing?

First, it’s not certain that listing only seven (well, eight right now) available apartments—most with an incentive for one free month (plus no broker fee)—means the remainder are leased.

It’s plausible they’re trying to maintain some scarcity. Keep in mind that many initial leases, at the beginning of 2024, came with two months free.

A good place to live?

The towers look spiffy, and a lot of people seem happy living there. On the other hand, some living in the western half of the West Tower report being plagued by noise from the adjacent dog run, which 1) was not supposed to be there in the first place and 2) is not well buffered.

That’s part of why the 23 Google reviews for the building average out at 3.0.

The very-hard-to-reach Pacific Park Conservatory, which oversees the open space, recently announced it would limit the hours of the dog run, to try to reduce the noise.

How “affordable” is the housing?

Yes, there are 240 below-market units aimed at middle-income households earning 130% of Area Median Income (AMI), which in most cases is six figures, all thanks to the 421-a tax break.

Though “affordable,” given the loose definition applied to income-targeted apartments, they hardly help the people who rallied for the project with great hopes and expectations.

Look at the far right column of the infographic below, which shows that the “affordable” apartments at 595 Dean, though relative bargains for their tenants, are hardly inexpensive: $2,290 for a studio, $2,690 for a 1-BR, and $3,360 for a 2-BR.

That’s why the successor to 421-a, the 485-x tax break passed earlier this year, no longer includes the option for 130% AMI units and that option was widely seen as bad policy, even by industry supporters. One real estate lawyer said it was a “mistake” that gave the tax break a bad name.

Skewed guidelines

Fun fact: under 2024 guidelines, which were not operative for this building, a studio at 130% of AMI could rent for $3,532, which is above market-rate. The least expensive market-rate unit is listed at $3,405, which, with one month free, translates into $3,121 net effective rent, albeit for only a year.

Under the 2022 guidelines, “affordable” studios could’ve rented for $3,035, but again, there wouldn’t have been (much of) a market, which is why rent was set at $2,290.

Affordable housing = smaller units?

In June, I quoted a lawyer for Empire State Development (ESD), the state authority that oversees/shepherds the project: "The buildings are up, people can see them. The units, the same units that are market-rate units, are occupied by the affordable tenants."

I wrote that that was true for the five buildings that contained both market and affordable units.

Except it’s not.

A perusal of message boards regarding the building, especially focused on the affordable units, delivers some mixed opinions. “The studios are ridiculously small and they have no w/d in unit,” wrote one applicant on City-Data.com. “Amenities are mid and $50 a month per tenant. Swimming pool is $500 a season and is not prorated if you start late lmao.”

”Haven't moved in yet but was in the area today and it was busy with families, couples in the restaurants. I imagine in summer it will be a hub of activity,” wrote another. “I am currently in a 2 bedroom pre-war (2 people) so everything seems tiny to me. I'm all about atmosphere so the amenities plus the area seems a plus.”

Another backed out, writing, “I couldn't stomach doubling my rent for such a small space,” while another wrote, “oh my lord the units and building itself are gorgeous!”

One Reddit commenter lamented that “The unit was significantly smaller than the pictures suggested on Housing Connect.. The bedroom could barely fit a queen-sized bed without it touching the window.”

”We also looked at some video tours on YouTube, which showcased more spacious and nicer apartments,” the writer added. “When we brought up these differences to the leasing agent, we were told those were market-rate units, and ours was reduced-price.”

One commenter agreed that their 1-BR was “significantly smaller than other units in my building. I highly doubt they could rent this unit at market price anyway, but I live alone and am happy with my lottery experience.”

”Yes they are super small!” added another. “The 2bedroom lottery apts only have one bathroom, whereas the 2 bedroom market rates have two bathrooms.”

That’s only slightly inaccurate: of 63 previously rented market-rate two-bedroom units, only four have one bathroom, according to StreetEasy. The one 2-BR currently available has two bathrooms.

Another hailed “mainly a good experience so far. The amenities and neighborhood are really nice. We were also lucky enough to get a unit with w/d. Only downside is we do hear that dripping sound that has been mentioned before…”

What about the “park”?

No, the buildings don’t come with a 60,000-square-foot “public park.”

It’s privately managed, publicly accessible open space, nicely executed but very much preliminary. Only about 3 acres of open space are complete, with 8 acres promised, and planned. That depends on a full buildout of the project.

That’s why there’s a fence separating the open space from demapped Pacific Street, and the railyard behind it.

Moreover, if the project is supersized as has been proposed, with larger buildings, the ratio of “park” to residents would diminish even more.

A public park is answerable to the city Parks Department. This private open space is answerable to the murky Pacific Park Conservancy, which has no staff—and whose phone number was dead until well after I pointed it out

About the retail

So, yes, there are now two restaurants at the inner front of the towers, Simo Pizza and Nin Hao (Fujuianese), plus a fieldhouse and fitness center for Chelsea Piers.

Unmentioned: two sketchy things about the latter.

First, the developer was given the opportunity to cut down the required below-ground parking and swap in space for Chelsea Piers, with neither any additional review by the state, beyond a Technical Memorandum, nor any reciprocity in public benefit, as the BrooklynSpeaks coalition sought.

Was this residential, commercial, or retail space, all of which had square footage limits? No, it was… recreational space, a new category that evaded review.

Moreover, these two towers, strangely enough, have just one lobby, in the West Tower, which means those entering the East Tower have to overshoot their building and then travel underground.

That allows Chelsea Piers to monopolize the lobby of the East Tower.

What about “Develop Don’t Destroy”?

In the article, Engquist took the chance to slam “Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn [which] plagued the proposal with lawsuits and protests.”

The now-defunct DDDB did far more than plague the proposal. It relentlessly pointed to the lies and deceptions behind the project, reasons not to trust original developer Forest City Ratner, which made extravagant claims of public benefits but ultimately followed the bottom line—and begged off responsibility.

Moreover, it didn’t simply aim to stop Forest City’s project but also recruited an alternate developer, Extell, to bid on the key piece of public property, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s Vanderbilt Yard, and propose a large—though not as nearly as large—project, without an arena.

Changing times

Engquist’s right that “[t]he project did not destroy Brooklyn” and, implicitly, that such criticisms were overwrought.

Nor, however, did the project’s Community Benefits Agreement meet the developer’s aspirations: to “maximize the benefits of the Project to residents of Brooklyn, as well as minority and women construction, professional and operational workers and business owners and thereby to encourage systemic changes in the traditional ways of doing business on large urban development projects.”

That said, the response to Atlantic Yards was premised, initially, on a promised ten-year timeline, well before recognition that the Downtown Brooklyn rezoning would deliver much more density, not far away, changing people’s perspective.

It also was premised on a promised 20,000-seat arena, larger than the downsized current version (capacity 17,732 for basketball).

Also, crucially, significant numbers of fans of the New Jersey Nets were expected to drive to Brooklyn for games, causing traffic snags and having a larger impact on nearby neighborhoods.

What’s next?

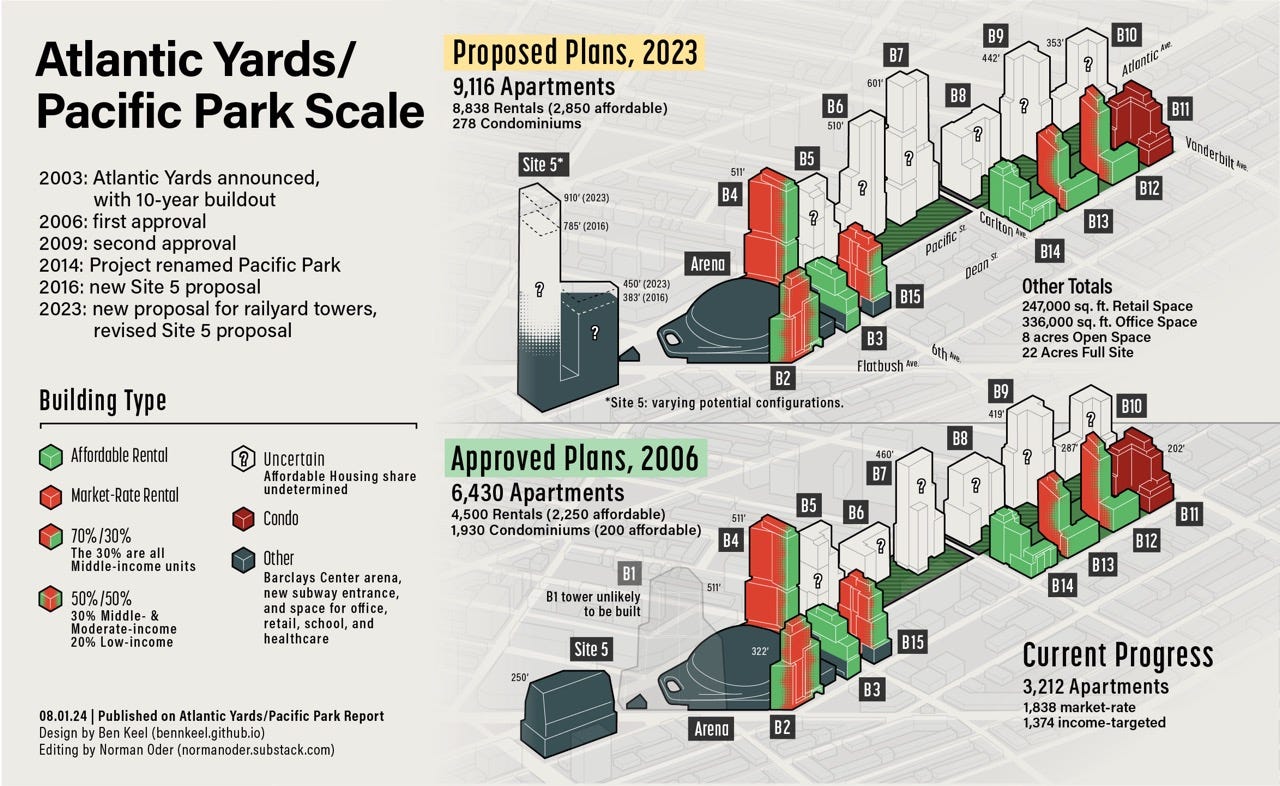

It’s worth noting that the project is less than half-finished, with sites for six unbuilt towers over the Vanderbilt Yards and a large two-tower project planned for Site 5, catercorner to the arena.

Even before I learned of plans to supersize the project, enlarging the already approved towers (as portrayed above), I commissioned graphic designer Ben Keel to portray what the view of towers along Atlantic Avenue might look like.

It’s likely that towers would be significantly larger, so much so that the developer last year asked to turn part of Pacific Street into public open space, presumably to both provide a buffer and ensure that the ratio of open space to residents doesn’t shrink too much.

Would building them “destroy” Brooklyn or the neighborhood? No.

However, everything is an experiment, as some old Atlantic Yards hands used to say, and the concentration of density—far more than what’s already been delivered—may deliver housing at the expense of urbanity.

That’s why my May overview in Urban Omnibus of Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park history, Watch This Space, ended with “Civic fatigue stifles public discussion of the contours and urban impact of the railyard buildout.”

Again, that was before we knew the developer had sought to add 1 million square feet of bulk. We shouldn’t let real-estate triumphalism reify civic fatigue.

As someone who has been living in a 595 Dean lotto 1 bed for the last year, it is untrue that the lotto units are identical to the market units. I’ve been in the market-rate 1 beds across from me.

They had brand new, top-of-the-line appliances such as a fancy gas stove, washer dryer in unit, nicer microwave and fridge, quieter side of the building with better light, and most importantly, much more square footage.

My apartment has budget appliances and is plagued by dog barking at the park, an odd layout that is hard to work around, and much less square footage.