The Atlantic Yards Independent Compliance Monitor Was Never Hired

The much-hyped Community Benefits Agreement, with promises of jobs, contracting, and housing, was supposed to be accountable. They promised, on video.

This is updates and revises an article from April 2014.

I was recently asked for some summary statistics—promises and realities—about Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park. (Stay tuned.)

Some are relatively easy to compile, such as the record on affordable housing: 1,374 apartments out of 2,250 required units. There’s a skew to middle-income units, while low-income ones are vastly behind promises.

Others, such as the record of hiring minorities and women, or contracting with MWBEs (minority- and women-owned business enterprises), or job training, are tougher to assess, because there are no official reports.

They all were promised in the much-hyped Atlantic Yards Community Benefits Agreement (CBA), a private contract between original developer Forest City Ratner and eight purported community partners, only two of which had any track record.

It wasn’t supposed to be that way. As I wrote in 2014, a fundamental issue regarding the project was accountability, trust, and oversight, and the developer—and, by extension, New York State—had fallen short.

The clearest, most basic example of that was Forest City’s failure to hire the Independent Compliance Monitor required in the CBA. The firm’s executives and partners publicly promised that monitor both before the CBA was signed and later at the signing.

With no monitor, there was no public assessment.

Nor did the CBA signatories, most of which were fledgling and had no budget for litigation, try to enforce the contract. (“Forest City has funding obligations and commitments to each," CEO MaryAnne Gilmartin said in July 2009, suggesting a situation of dependence.)

And today?

Today, the CBA is essentially defunct, though one of the eight signatories, the Downtown Brooklyn Neighborhood Alliance (DBNA), still distributes free tickets to arena events. A successor to signatory ACORN, the Mutual Housing Association of New York (MHANY), helps process the affordable housing.

(Note: separate from the CBA, the Social Justice Fund of the Joe and Clara Tsai Foundation—the owners of the Nets and the arena company—since 2020 has established various initiatives, including a loan fund and grants to local businesses, that in a few ways reflect CBA promises, and have won local support.)

Looking at the CBA promise, on video

Consider former Forest City VP Jim Stuckey at a public meeting in November 2004.

"Let’s talk about Community Benefits Agreements," Stuckey said. "We doing something here that is historic. Never been done in New York City before. And what we’re doing is that we’ve agreed to enter into a legally-binding Community Benefits Agreement that will be monitored by an independent monitoring group not associated with anybody who actually negotiates that agreement."

Note the enthusiastic claps by supporters, suggesting it a validation of the company's plan. (The first three videos are footage from directors of the 2011 documentary Battle for Brooklyn, which will be screened Feb. 28.)

"And we’re doing that because not only do we believe that we should do the things that we say we will do, just as we have in the past"--note Stuckey's somewhat defensive tone--"but we also believe that should set the bar. We also believe that what we do should be done by others."

Another promise, on video

In the video below, from that same event, Stuckey cited "a legally binding contract that will be enforceable the way any contract under law will be enforceable."

"Whether or not that becomes part of the public approval process, and part of the city and state's development plan, remains to be to be seen," Stuckey continued. "But if it's not, in and of itself, we have agreed it will be a legally binding agreement, enforceable, under law, with an independent monitoring body."

"Which law?" shouted a skeptic. (The issue, it turns out, wasn’t the law, which was never tested, but the signatories’ willingness to pursue enforcement. In some CBAs, government entities have the ability to do so.)

Another promise

Around the same time, Stuckey spoke at a meeting of Brooklyn Community Board 2.

"And a Community Benefits Agreement is something that we believe is more than just talking about what few things we can do for the community," he said. "It's a chance to talk about systemic change. It's a chance to talk about the jobs and housing and the other things that will result from this project."

"So we began earlier this year," Stuckey said, "in fact, we were first invited, I guess back in April by the Downtown Brooklyn Leadership Coalition, and we were asked, Would you be willing to enter into a Community Benefits Agreement?, and we said yes. We were asked, Would you be willing to have that be a legally binding agreement?, and we said yes. And we were asked, Would you be willing to have that be monitored, an independent monitoring, to be sure that what you say you'll agree to you in fact will do?, and we said yes."

Actually, they weren't first invited "back in April" but rather helped establish the CBA in meetings that February at Forest City offices.

Deflecting the issue

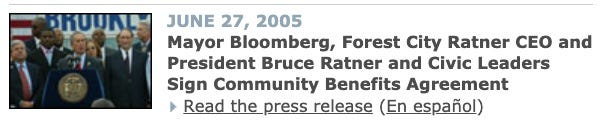

At the signing ceremony, the Rev. Herbert Daughtry of the Downtown Brooklyn Neighborhood Alliance stressed that "the developers have agreed to fund an independent monitoring agent." Developer Bruce Ratner said he aimed to exceed the CBA's goals, "but if we don't, there can be litigation."

Mayor Mike Bloomberg interjected: "You have Bruce Ratner's word, and that should be enough for you, and for everybody else."

The Brooklyn Paper, at that point independently owned and highly critical of Atlantic Yards, sardonically headlined its coverage, IN BRUCE WE TRUST.

That skepticism was wise.

Getting to a monitor?

There seemed to be progress. In March 2007, a press release issued by a Forest City Ratner-paid public relations firm in was headlined "ATLANTIC YARDS CBA COALITION SEEKS INDEPENDENT COMPLIANCE MONITOR: 'Watchdog' To Ensure Community Benefits for Local Community and Residents."

“Atlantic Yards is setting a new standard for inclusion and community involvement for a development, and the ICM will be everyone’s watchdog to ensure we reach all of the goals and benefits we have agreed to in the CBA," Ratner said.

It never happened.

Questioning Forest City

FCR was not publicly questioned about the ICM until a Sept. 29, 2010, public information session at Brooklyn Borough Hall, mainly concerning the planned arena plaza.

As shown in the video below, Carlo Scissura, then Chief of Staff to the Brooklyn Borough President, read a question submitted by an audience member (me): "Forest City Ratner was supposed to hire an independent compliance monitor for the CBA. What happened to that monitor and who is it?"

The misleading, somewhat uncertain response came from Forest City Ratner executive Jane Marshall. (Video by Jonathan Barkey.)

"The CBA agreement was signed a long time ago," Marshall responded. "It didn't actually go into effect until we broke ground for the arena."

Lack of credibility

The CBA was signed on June 27, 2005. The ceremonial arena groundbreaking was held on March 11, 2010. The CBA clearly contradicts Marshall's claim. Also, in several places, the CBA indicates that implementation would begin soon after it was signed, rather than some unspecified later groundbreaking.

Marshall finished up: "And the other thing is that, when we do that, it will be something that the Executive Committee, the groups themselves, probably issue an RFP and select a monitor, based on the scope of work that they--have deemed is directly related to everybody's mandate, and hopefully we'll get it done soon, but I don't have the timetable right now."

Such an RFP had begun three and a half years earlier, in March 2007.

They [FCR] are going to retain a compliance monitor per the CBA, but they are going to wait until the housing phase,” a spokesman told the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in January 2012.

The Rev. Daughtry told the Eagle: "The point is that I feel, whether they [FCR] have reneged on promises, I’m not concerned about it." By contrast, in March 2005 he had said of Ratner, “If he doesn’t honor this agreement I will do all in my power to make downtown Brooklyn as ungovernable as possible.”

Bertha Lewis, the former CEO of ACORN, did not respond to the Eagle's query, but had defended the CBA in May 2006 by noting that it calls for an independent monitoring body that “does not have a dog in this fight” to oversee implementation.

What happened?

Why wasn’t the monitor hired? It’s not unlikely they didn’t want a monitor to show they’d fallen short.

However, we never quite got an answer.

According to the February 2014 Response to Comments document, which was part of the Draft Scope of a Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (SEIS), the coalition BrooklynSpeaks noted that the executive committee of the CBA board was supposed to hire an ICM funded by Forest City, "as soon as reasonably practicable" following the signing of the agreement in June 2005.

BrooklynSpeaks argued that the upcoming SEIS should assess the impact of failing to hire the ICMl. However, Empire State Development, the state authority that oversees/shepherds the project, responded that it had no involvement in the CBA.

The issue came up later that year, in a lawsuit filed by members of a Pre-Apprenticeship Training Program against Forest City and the job-training group BUILD, a CBA signatory. They claimed they’d been denied promised paths to union construction careers.

In a deposition, Ratner was asked why the ICM wasn’t hired. "I can't really answer why not,” he responded, evasively. “I don't even know why not.”

If you want to see where the community benefits agreement money was spent. See https://prop.tidalforce.org/elections?nys-election-details%5Bquery%5D=Bruce%20ratner&nys-election-details%5BsortBy%5D=nys-election-details%2Fsort%2FORG_AMTint%3Adesc

The community does not guarantee any votes. We can see ratner's name is associated with $300, 000 in campaign money just in the state and city.