FAQ: Where Do Things Stand with Atlantic Yards?

A joint venture, in two variations, may take over, but scale, scope, promises, and timing are TBD. Could public input make a difference, especially after NY State suspended penalties?

Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park may be on the verge of big changes, as we learned at an Aug. 6 meeting of the advisory Atlantic Yards Community Development Corporation (AY CDC). But we don’t know the details.

(Here’s my collected coverage; I’ll send my bi-weekly digest soon.)

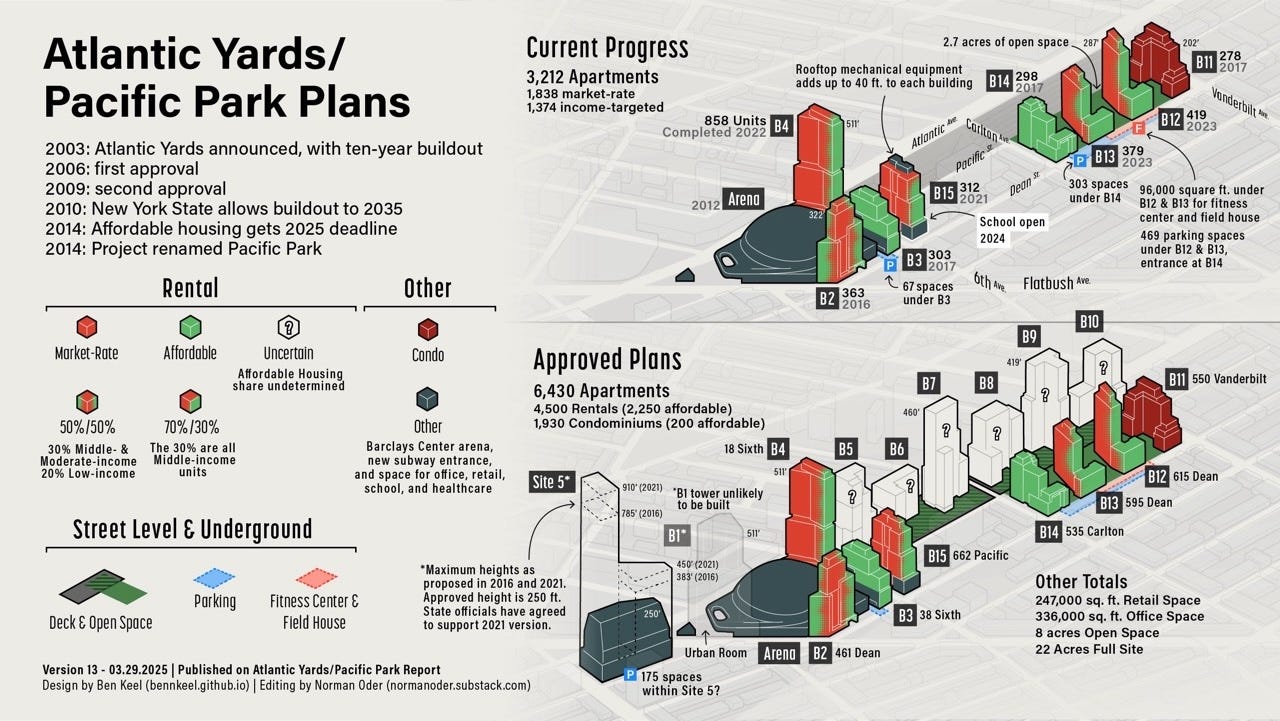

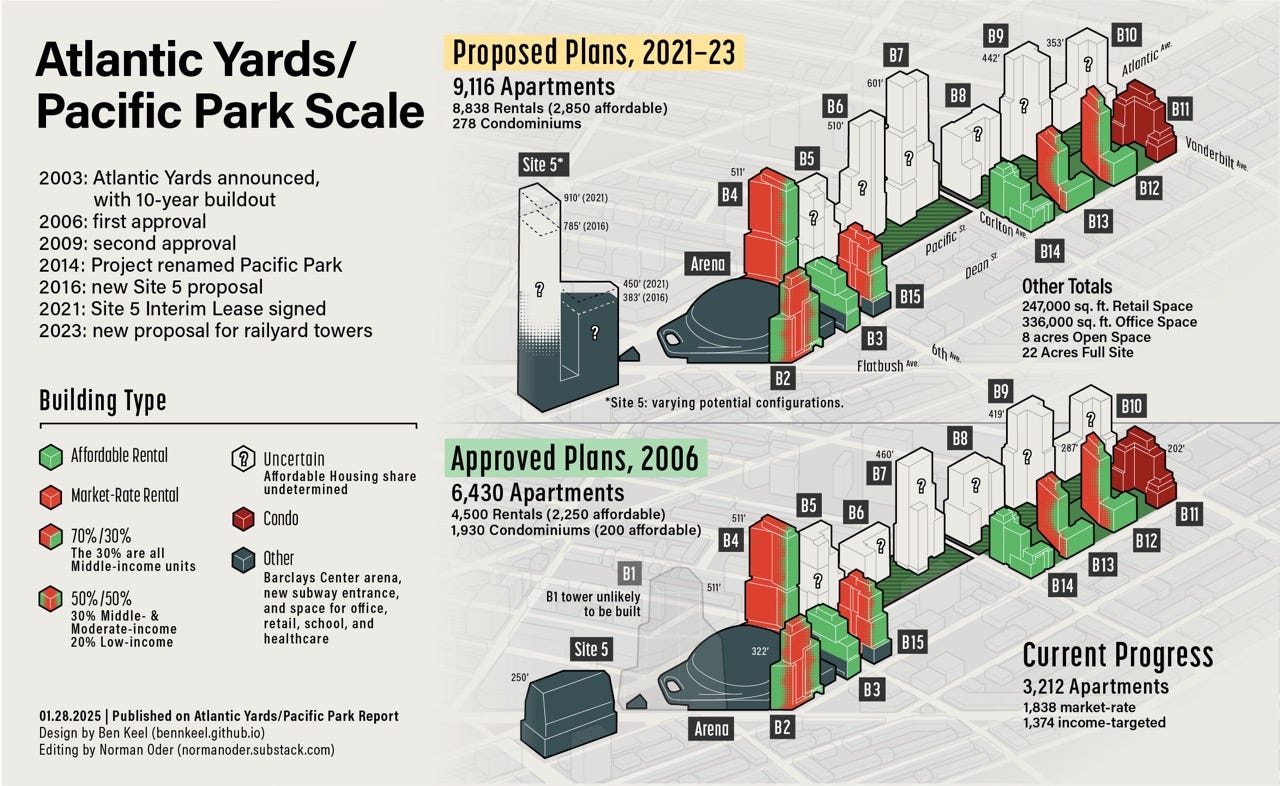

A new set of developers—two related but different joint ventures—are poised to be named “permitted developers” for the remaining eight towers, which would be built at seven sites: B5-B10, over the railyard, and Site 5, catercorner to the arena.

At the same time, Empire State Development (ESD), the state authority that oversees/shepherds the project, has hired a public engagement consultant to elicit community preferences—affordable housing? public space?—for the remaining buildout.

That, however, comes with three complications.

First, ESD’s failure to enforce a May 2025 deadline for the project’s 876 remaining required affordable housing units, with $2,000/month penalties for each missing unit, undermines confidence in any future promises, even one purportedly guaranteed by a new contract.

Second, without a proposed plan—how big? how many apartments? how many affordable units? what timeline?—it’s difficult to know how public input might make a difference.

Third, there’s an inevitable tension between financial viability/profit, public benefits, scale, and neighborhood impact—and without knowing more about the developers’ financial deals, it’s hard to assess that.

One complication is that, to monetize the six towers over the railyard, an expensive platform must be built over the railyard, a key component of the purported “blight” that justified the state’s use of eminent domain. That would incentivize the developers to ask for more.

What next?

We know, as I reported last year, that zombie master developer Greenland USA in 2023 proposed expanding the towers’ height and density, adding perhaps 2,700 more apartments, and promising more affordable housing, albeit on a delayed timetable.

A proposal along those lines likely could recur. Until we see that, and understand the financial underpinnings, it would be hard to see public input as meaningful.

But let’s see the rest of the questions.

How long has the project been stalled?

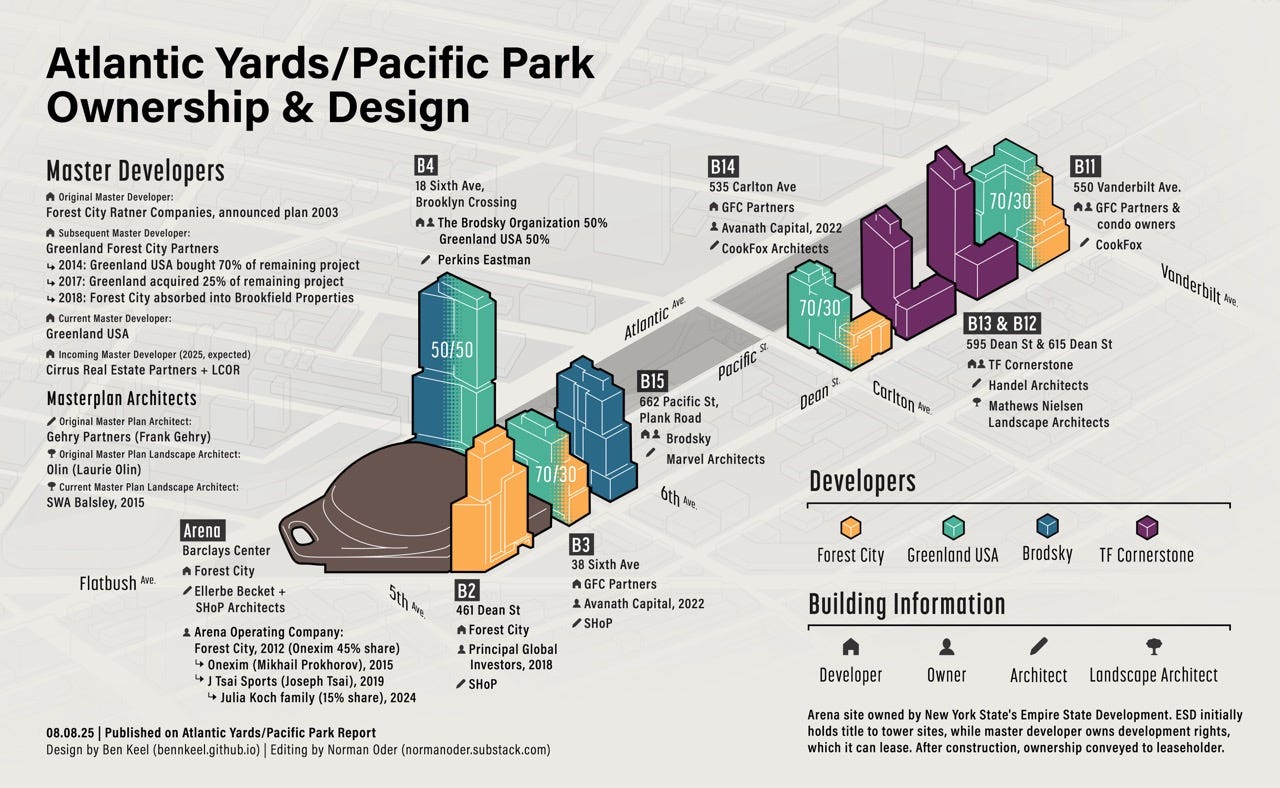

It’s been formally stalled since November 2023, when a foreclosure was threatened regarding Greenland USA’s rights—apparently, partial rights—to develop the six large towers east of the Barclays Center, over the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s Vanderbilt Yard.

But no new construction came after the 595 Dean (B12/B13) towers on the southeast block, which were announced in late 2019 and started opening in spring 2023.

What was the trigger?

In 2014, Greenland and original developer Forest City Ratner, which later bowed out, borrowed $349 million in two tranches, $249 million and $100 million, from immigrant investors (from China) under the EB-5 investor visa program. The program grants green cards for investors and their families in exchange for purportedly job-creating investments. (It’s mostly bogus, I’d contend.)

Greenland repaid only about $63 million of the low-cost loans, leaving $286 million unpaid. The U.S. Immigration Fund (USIF), a private company known as a “regional center” which recruited the investors and organized/managed the loan, could then pursue foreclosure.

How could the middleman manage the foreclosure?

It’s not quite clear, but the USIF, as manager, could control the “company” created for each EB-5 investment. A USIF affiliate also apparently is now a creditor, as some EB-5 investors have moved their money to another USIF project.

Similarly, Fortress Investment Group, a private equity fund that regularly partners with the USIF, is also a creditor, as EB-5 investors have moved their money to another project.

The USIF couldn’t proceed with the foreclosure?

No. ESD requires a “permitted developer,” one with at least ten years of a experience in large-scale projects, to take over. USIF and Fortress don’t qualify.

Last year, it emerged that Related Companies, developer of Hudson Yards, was considering entering the project. That evaporated early this year.

Cirrus Real Estate Partners, a new company financed in part with money from the building unions’ pension funds, entered early this year. Later, they allied with LCOR, a development firm with widespread experience.

They’re not the only players, right?

As we learned, Cirrus and LCOR will take the lead on the six railyard sites, with the USIF and Fortress in the background, and Greenland retaining a role.

Wasn’t the USIF in the driver’s seat?

A lot of people, including me, thought so. But the flowchart I created, with my frequent collaborator Ben Keel, was apparently incomplete.

Greenland has long controlled the entities at far right in the chart below, the Atlantic Yards Venture and the affiliated AY Phase II Development Company.

Entities created by the affiliate, AY Phase II Mezzanine and AY Phase III Mezzanine, borrowed the EB-5 funds and offered, as collateral, development rights—er, partial development rights, apparently—to the six railyard sites.

Apparently, Greenland retained equity in AY Phase II Development Company (or maybe just Atlantic Yards Venture?), related to its embedded investment, with Forest City, creating precursor elements for the platform.

How could that be more valuable than $286 million?

Unclear.

But the value of Greenland’s investment likely includes a cumulative total of $96 million paid to the MTA by June 2023, with an additional $77 million due after that, in annual $11 million increments, by June 1, 2030, for vertical development rights.

Greenland didn’t pay in 2024, right?

Correct. The $11 million payment was from two USIF entities. That suggests that company was getting ready to take over the project. But it didn’t.

Who paid in 2025?

Unclear. The payment may have been suspended. That MTA is rather closemouthed about such inquiries.

If the EB-5 creditors are owed more, why aren’t they in control?

Now I must speculate. The EB-5 creditors are owed $286 million, and the collateral is the rights—partial rights—to six towers, within AY Phase II Development Company.

It’s not clear how could Cirrus (and LCOR), by taking control of Greenland’s remaining basis, retain control. But it’s possible that the Greenland entity contains various classes of assets, and the “Mezzanine” entities are subordinate.

Why don’t we know more?

ESD should explain this to the public, perhaps at the next AY CDC meeting. How much does each company own? What are the contingencies regarding Greenland’s assets? Does Cirrus’s control reflect its investment, or something else?

What about Site 5?

Site 5, longtime home to the big-box stores P.C. Richard and the now-closed Modell’s,1 was not part of the foreclosure.

It and the parcel known as B1, the tower slated to be built over the arena, are retained by Greenland. We learned that Cirrus and LCOR, with Greenland as a subordinate partner, plan to develop Site 5. (The USIF and Fortress wouldn’t be involved.)

What would they build?

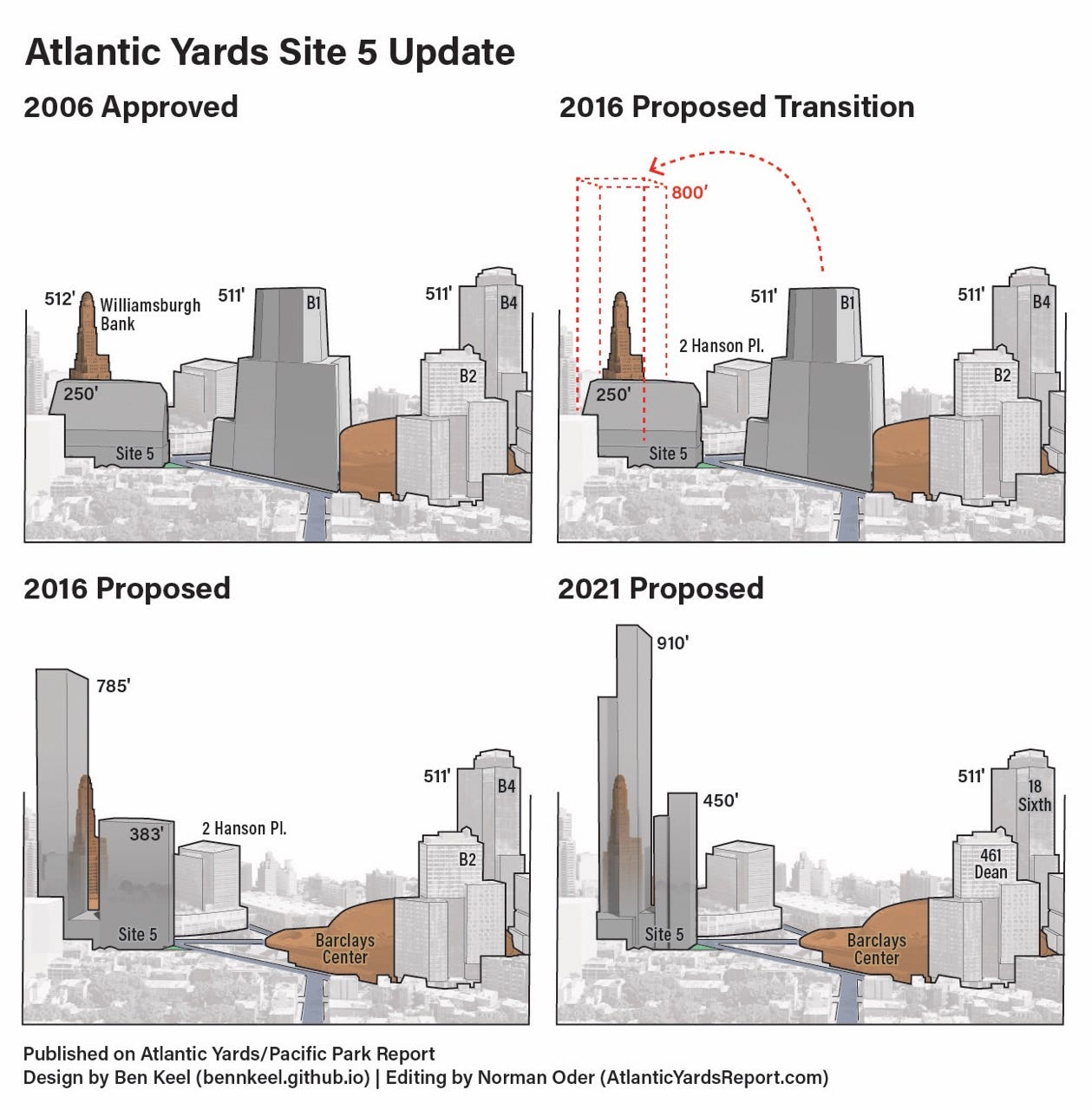

Unclear. Site 5 in 2006 was approved for a 250-foot, 439,050 square foot tower. B1 was approved for a 620-foot, 1.1 million square foot tower, though developer Forest City, at the last minute, agreed to lower the height to 511 feet, without decreasing the bulk.2

Since 2015-16, the developers—first Greenland Forest City Partner, then Greenland—have contemplated moving most of the bulk from B1 across Flatbush Avenue to Site 5, creating a giant, two-tower project.

As of 2016, the taller of the two towers would’ve been 785 feet; as of 2021 revised plan, it would be 910 feet.

In 2021, ESD agreed to support a plan with some 1.242 million total square feet, a 550-room hotel, LED signage outside, and retail instead of previously promised below-grade parking.

They can’t just do that, right?

They need permission from ESD, which must revise the project’s guiding Modified General Project Plan and Development Agreement. So ESD Board Members, who are appointed by the governor, will have to rubber-stamp3 the change.

Who would gain?

Well, unlocking the square footage could create a parcel with some $250 million to $400 million worth of developable square feet, as I wrote, potentially giving Greenland, which is struggling financially, a nice payday.4

It also would hugely benefit BSE Global, which operates the arena and owns the Brooklyn Nets and New York Liberty, and is controlled by Alibaba billionaire Joe Tsai (and wife Clara Wu Tsai), with a 15% minority stake from the family of Julia Koch, widow of the right-wing billionaire David Koch.

How would BSE Global benefit?

They sure don’t want to operate an arena during construction of a giant tower, nor after that tower is built. They wouldn’t have places for crowds to gather or to put up promotional art exhibits or free performances. They wouldn’t have the same canvas for digital advertising and promotional messages.

Why should they pay?

It’s unconscionable that the big winners in this state-assisted project5 are the billionaire Mikhail Prokhorov, owner of the Nets and the arena company, and the billionaire Tsais.

You could argue that the Tsais (and, later, the Koch family) invested in the ever valuable Brooklyn Nets, a scarce commodity in a cartel-like league, knowing that interference from B1 construction was a legal, if not likely, outcome. They took that risk.

The huge increase in the valuation of the Nets, arena, and Liberty relates not just to a boom in NBA values and the Tsais’ savvy investments but also the presence of an arena in the world’s media capital and the NBA. The public deserves reciprocity.

ESD has power it hasn’t exercised against BSE Global, much less Greenland.

Why hasn’t ESD pursued liquidated damages?

A settlement reached in 2014 with the coalition BrooklynSpeaks, which had threatened a lawsuit on the grounds that delays in affordable housing raised fair-housing claims, established a May 31, 2025 deadline for the 2,250 units of affordable housing.

Of that total, 876 remain to be built, and should have triggered $2,000/month in liquidated damages, which would go to a city affordable housing trust fund.

ESD, claiming it would rather get the project re-started, initially said it would not pursue penalties while negotiating with a new development team.

We later learned another reason: ESD’s afraid Greenland might sue. Greenland has argued that it’s faced Unavoidable Delay and an Affordable Housing Subsidy Unavailability, both terms defined in the project’s guiding Development Agreement.

Greenland may have some case, at minimum, for COVID-related delays. ESD says it disagrees with the developer’s contention, but doesn’t want a legal battle that would stall progress.

Could this proceed on “two tracks”?

At the AY CDC meeting, ESD executives were asked whether they could proceed on two tracks: dunning Greenland for the $1.752 million/month in damages, while proceeding to negotiate new plans with Cirrus and LCOR, with Greenland as a junior financial partner.

They said no. Perhaps they’ve been reminded that a legal battle between P.C. Richard and original developer Forest City Ratner stalled discussion of plans for Site 5.

Sure, litigation is a risk, but, as I’ve argued, ESD has much unused leverage, since it could slow or prevent the transfer of the B1 bulk. Also, state agencies tend to see their decisions upheld in court.

Meanwhile, cash-strapped Greenland wants to monetize its embedded investment in the railyard sites and Site 5/B1. So litigation would delay that.

ESD’s upper hand could push Greenland to negotiate a settlement, perhaps a limit on damages, or a particular fraction of Greenland’s share.

Didn’t a real-estate consultant warn against pursuing damages?

Yes, Jordan Barowitz, long associated with a major real-estate company, told Gothamist that the project’s “not economical. Collecting more fines just makes it less likely the project gets built.”

He’s no neutral arbiter, I noted, and perhaps someone else would have a different opinion.

Maybe even developer Alicia Glen, who as Deputy Mayor under Mayor Bill de Blasio negotiated the 2014 agreement, was interviewed by The Real Deal in December 2023:

Glen said the state should work with Greenland to transfer the development rights to avoid delaying the project further, but that the penalties should remain.

“You have to reestablish a basic contract between the government and the communities in which you are building,” Glen said. “And if you can’t do that, you are endangering the whole endeavor.”

Might Glen be influenced by ESD’s claims that it can’t work on two tracks? Alternatively, she might listen to her statement that contracts should be meaningful, and consider that suspending penalties would reward speculators.

How would speculators benefit?

All the parties might be considered speculators.

First, the initial BSE Global transaction with Prokhorov, buying the arena company and Brooklyn Nets, was in 2017, culminating two years later.

Whatever the private promises Prokhorov may have gotten (and transmitted), the purchase came with the risk that the valuable branded plaza might not be permanent, and that a giant tower might be built.

Similarly, when Greenland invested in 2014, buying 70% of the project going forward and later acquiring essentially the remainder (though selling off individual site leases), that came with the risk that they might not be able to monetize the B1 tower.

Also, the price Cirrus and LCOR paid—or agreed to pay—to enter the project surely included a discount for the many risks, including the challenge in monetizing the B1 bulk and the time it might take to activate the railyard sites.

What are these companies’ goals?

They’re businesses. They want to make money and, in the case of Cirrus, ensure that the building trades are involved, since those unions’ pension funds are putting up some of the money.

They may pay lip service to the public interest, but they don’t answer to the public. Cirrus's stated goal to "generate consistent, attractive returns through identifying investments that offer asymmetric risk-return profiles and significant downside protection."

How are they held publicly accountable?

That’s the job of government. That said, ESD answers to the Governor, who wants to get things started, to get more housing built.

Public accountability would mean not just delivering a new start to the project, with new promises of public benefits and a new timetable.

It also would mean a fair assessment to balance the impacts of construction, project operations, and arena operations, while recognizing that the state-supported project has enriched billionaires without reciprocity.

That might require separate, third-party experts charged to represent the public interest and assess project impacts, project viability, and alternatives. (Yeah, ESD is supposed to do that, but it answers to the governor.)

How much, for example, could payments from BSE Global support new public benefits?

Why should Greenland be allowed to cash out?

Who are the players?

Few people visibly care much about Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park today, though presumably new plans will rouse immediate neighbors, neighborhood groups, affordable housing advocates, labor unions, and YIMBY/Abundance housing supply enthusiasts.

For now, the main vector for community input is the coalition BrooklynSpeaks, made up of “civic associations, community-based organizations, and advocacy groups” concerned about the project.

BrooklynSpeaks, which has the ear of local elected officials, was the “mend it don’t end it” to the now-defunct Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn, which aimed to stop the project.

BrooklynSpeaks has neither staff nor officers, and is led by a handful of people, as far as I can tell.

They are Gib Veconi of the Prospect Heights Neighborhood Development Corporation, a neighborhood group that has advocated for, among other things, a landmark district and open streets; Michelle de la Uz of the Fifth Avenue Committee, an affordable housing nonprofit which has allied with developers that promise additional affordable units in exchange for greater density; and Assemblymember Jo Anne Simon, who as head of the Boerum Hill Association advocated for thoughtful high-rise development along Downtown Brooklyn’s once-blighted Schermerhorn Street corridor.

BMT as template for AY?

It was interesting to see how, regarding the pending Brooklyn Marine Terminal (BMT) plan for Red Hook and Columbia Heights, Simon was wary of the ambitious plan but de la Uz endorsed it.

(That doesn’t preclude revisions to get the BMT Task Force to yes.)

Both Cirrus and ESD unsurprisingly have met with BrooklynSpeaks representatives. They surely would like the organization, if not in support of the new plans, at least open to them.

“If they have some endgame that is actually aligned with the public interest, it would be good to hear that now,” de la Uz said at a press conference in June. “Because the longer they take to lay that out, the more likely we are to sue.”

Since then, BrooklynSpeaks launched a petition to ask Hochul to pursue enforcement.

What’s next?

Before “community engagement” proceeds, I’d expect another meeting of the (purportedly) advisory AY CDC, also set up after the 2014 settlement, which, as I wrote in May, was overhyped in the sunny New York Times scoop about the new affordable housing deadline.

The AY CDC is supposed to monitor project changes but often been ineffectual or ignored.

Veconi, the most informed and influential member on the AY CDC, also led the 2022 BrooklynSpeaks online charrettes--known as Crossroads--about the future of the project, including housing; urban design and street design, transportation; and accountability.

"At this stage, I think the accountability piece is going to be very important," Veconi said at the Aug. 6 AY CDC meeting. "That's a place where I think we're going to be confronted with the question: what's different this time?"

That’s a question for the AY CDC, the public, and also for BrooklynSpeaks. How could it endorse a new plan, with new promises, given the track record? What new safeguards could be offered? And would that plan be worth the trade-offs?

Modell’s is being renovated into a short-term youth basketball facility for Brooklyn Basketball, an arm of BSE Global, which operates the arena and owns the Brooklyn Nets and New York Liberty.

That would’ve made the tower a symbolic one foot shorter than the Williamsburgh Savings Bank tower, then the borough’s tallest, but it would not have stopping blocking the tower’s signature clock. Today, several towers in Downtown Brooklyn well exceed the bank’s height, and the Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park tower 461 Dean Street (B2) blocks the bank’s clock for viewers looking northwest along Flatbush Avenue from Park Slope.

Sounds cynical? I’ve never seen a substantive debate among board members.

The value, which includes not just the vertical square footage but below-ground retail space and LED signage, is diminished by required public benefits like affordable housing and public space, an incentive to build bigger at what the City Planning Commission in 2006 called a transitional site.

The arena benefits from direct subsidies, tax breaks, a tax-exempt site, tax-exempt financing, the ability to sell naming rights (and other sponsorships), the state’s exercise of eminent domain, and even the city’s willingness to not enforce quality of life regulations.