As Housing Deadline Nears, NY State Punts on Penalties, Reviewing New Development Team. Cirrus JV Now Said to Include LCOR

BrooklynSpeaks, which in 2014 negotiated 2025 milestone, says public must be compensated for affordable housing not delivered

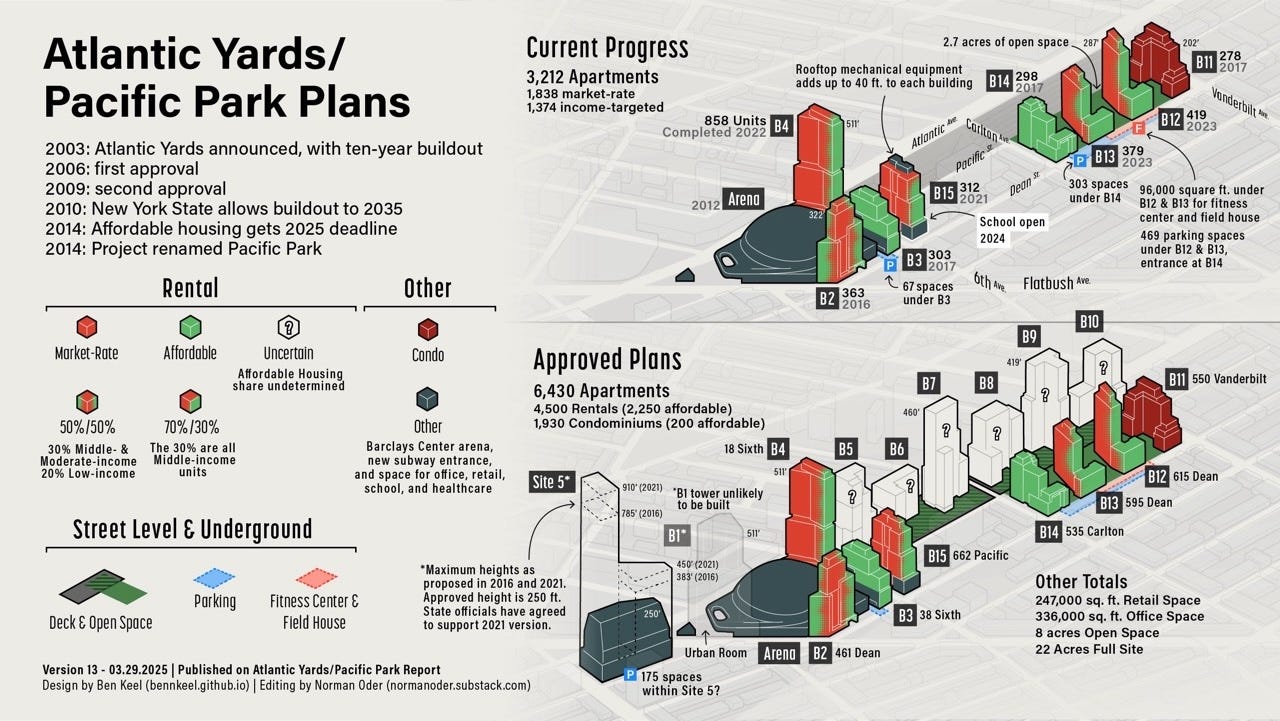

With a looming May 31 deadline to deliver 876 more units of affordable housing, Empire State Development (ESD), the state authority that oversees/shepherds Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park, yesterday refused to affirm that it would impose $2,000/month penalties for each missing unit, as required in a 2014 agreement.

Rather, ESD has moved the goalposts, encouraging a yet-unresolved transfer of development rights to six towers (B5-B10) over the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s Vanderbilt Yard. That requires an expensive platform as a precursor.

The decision generated criticism from those in the BrooklynSpeaks coalition that in 2014 negotiated the new deadline. At a meeting last night, Gib Veconi of the Prospect Heights Neighborhood Development Council (PHNDC) said the public “must be compensated” for the failure to deliver affordable housing.

To Gothamist, Michelle de la Uz of the Fifth Avenue Committee, called the move “unacceptable,” saying ESD couldn’t “unilaterally make that decision.”

Those development rights, held by developer Greenland USA, have been threatened with foreclosure since November 2023, once Greenland defaulted on $286 million in loans from EB-5 investors, who offer low-cost loans in exchange for green cards. Those six sites were offered as collateral.

“In an effort to move this process forward, ESD has set up an updated schedule of deliverable target deadlines for the development team while retaining all rights to issue liquidated damages,” the state authority said. (The statement was first published by The Real Deal.)

ESD said that involves “approval and transfer of development rights to a new team by August” and “a robust community engagement plan and project framework to be guided by a community engagement process by December.”

ESD didn’t mention the players, but, as noted below, they involve Cirrus Real Estate Partners, a company that surfaced on Jan. 31, and a previously unmentioned firm, LCOR.

The liquidated damages are supposed to go to the New York City Housing Trust Fund, administered by the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development, and to support affordable housing nearby, according to the settlement.

20 years of delay?

As background, ESD stated: “After more than two decades of delays, ESD is focused on unlocking progress—including the remaining affordable housing and the long-awaited development of the platform over the railyard.” That misreads history.

The project was not stalled for 20 years after developer Forest City Ratner announced it in December 2003. The arena was completed in 2012, the same year Forest City began the first tower, known as B2.

Greenland entered in 2014 just after Gov. Andrew Cuomo and ESD announced a “comprehensive plan to accelerate the development of Atlantic Yards, including a fast-tracked timeline”—ending this month!—to deliver the project’s 2,250 units of below-market affordable housing, which becomes more costly over time.

Yesterday, I wrote about that announcement and the need for skepticism about it.

“ESD’s goal is not simply to enforce penalties—but to ensure that after 20 years, this project finally delivers for Brooklyn,” the state authority said yesterday. However, that was what the 2014 agreement promised, with seeming teeth.

Either way, it seems unlikely that the 25-year “outside date” of 2035 to complete the full project will be met.

Public pushback

Presumably, ESD’s statement was aimed to restart the project without alienating future partners, to deliver more housing, and to afford Gov. Kathy Hochul a potential ribbon-cutting, as well as support from key labor unions allied with the project’s developer.

However, it doesn’t explain why the public gets by foregoing the liquidated damages—nor why any future assurances should be trusted.

The process won’t happen without some pushback. At a meeting last night, a leader of the BrooklynSpeaks coalition, which negotiated that 2014 agreement, said the public should be compensated for the failure to deliver affordable housing, especially given patterns of displacement in the areas near the Prospect Heights site.

Advocates plan a press conference next week to focus on that obligation, Veconi said at the group’s meeting last night. “This is something that elected officials in this part of Brooklyn are very concerned about, and we need to call attention to it.”

The funds—$1.752 million a month—”could be put to work right away” by bolstering affordability at some city-funded developments nearby, he said.

Though Veconi said that the obligation to collect liquidated damages can’t be changed without consent from the parties to the 2014 settlement, I don’t read it that way. However, those parties—civic groups in the BrooklynSpeaks coalition and four potential individual plaintiffs—could go to court to enforce the obligation.

In 2014, BrooklynSpeaks noted that the loss of Black residents in the four Community Districts near the Atlantic Yards site meant a potential fair-housing claim, given that those displaced would lose the community preference in the city’s affordable housing lotteries. That led to the new May 31, 2025 affordable housing deadline.

Joint venture expands to LCOR

The railyard sites have been in limbo since the foreclosure process was announced 18 months ago. No developer could move forward without 1) qualifying as a “permitted developer,” with at least a decade of experience in large-scale projects and 2) negotiating preliminary terms with ESD to make the project economically viable.

While ESD said yesterday that it’s reviewing a permitted developer application from the development team, it did not disclose the participants.

Veconi, however, indicated that a joint venture led by Cirrus Real Estate Partners, a new financing company that surfaced earlier this year, now involves the development firm LCOR, which has experience in residential development and public-private partnerships. That could enable the team to qualify as a permitted developer.

That suggests another twist in the project’s tangled development history. In 2014, nearly eleven years after it announced Atlantic Yards, Forest City sold 70% of the project going forward, to Greenland USA, part of a Shanghai-based company. (That excluded the Barclays Center and B2, the ill-fated modular tower.)

The joint venture Greenland Forest City Partners built three towers before Forest City began its exit. Greenland leased two development sites to TF Cornerstone and one to The Brodsky Organization. It built one tower with Brodsky.

Then, delayed by the pandemic and clashing with state agencies, Greenland ran out of money, failing to start the platform as planned and losing the opportunity for the state’s 421-a tax break.

Who are the parties?

It’s been tough to suss out who controls the collateral. The EB-5 investors, Chinese nationals, were disadvantaged by contractual language, which ensures that the manager of the loan fund, an affiliate of the Florida-based U.S. Immigration Fund (USIF), controls business decisions.

The USIF, led by Nicholas Mastroianni II and known for questionable business practices, also brought in Fortress Investment Group. It encouraged investors in the two loans to move their money to another Fortress project, thus leaving Fortress with a stake in the debt. (Mastroianni gave $50,000 to Hochul’s campaign in 2021.)

An affiliate of the USIF likely owns a piece of the debt. Last year—in an episode that remains murky—that affiliate, rather than Greenland, made the required $11 million annual payment to the MTA for railyard development rights.

A new developer might argue for an attenuated timetable, urging the MTA to allow smaller annual payments over a longer period, lasting past 2030.

Last year, the USIF began discussing a potential joint venture with Related Companies, known for projects like Hudson Yards.

Enter Cirrus

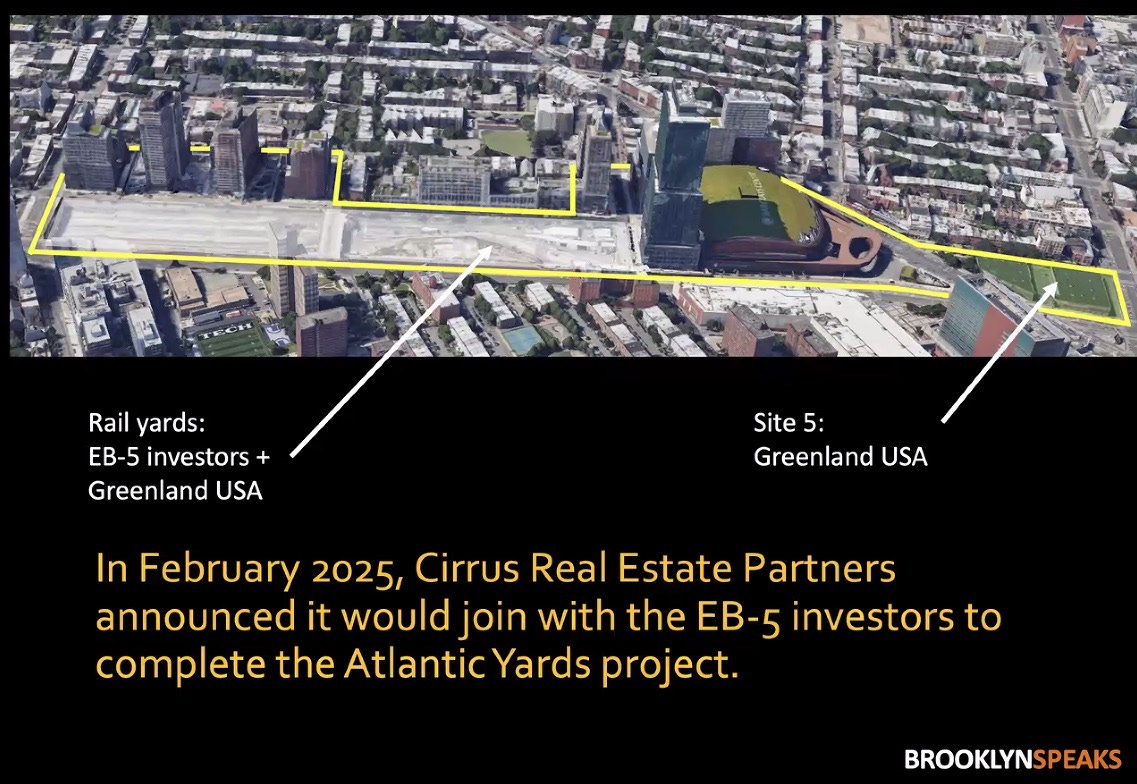

When, in late January, Related pulled out, the USIF announced the entry of Cirrus Real Estate, a new firm, whose affiliate Cirrus Workforce Housing has allied with construction unions on plans for “workforce housing,” accessible to union workers, using money from union pension funds.

Cirrus has announced a deal with Resorts World New York City for such housing. It’s appeared with both Mayor Eric Adams and Queens Borough President Donovan Richards and apparently has backing from leading Mayoral candidate Andrew Cuomo.

Cirrus in March began lobbying ESD regarding deal terms, including a tax abatement, potential funding, and, I suspect, permission to build a larger project, all of which would make Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park more—take your pick—financially viable or profitable.

The unspoken questions: just how much more additional bulk—free vertical land!—do they seek and what’s the impact on livability for both neighbors and new residents? In 2023, Greenland sought to rescue the project by building far bigger, while promising more affordable housing, albeit with newly relaxed deadlines.

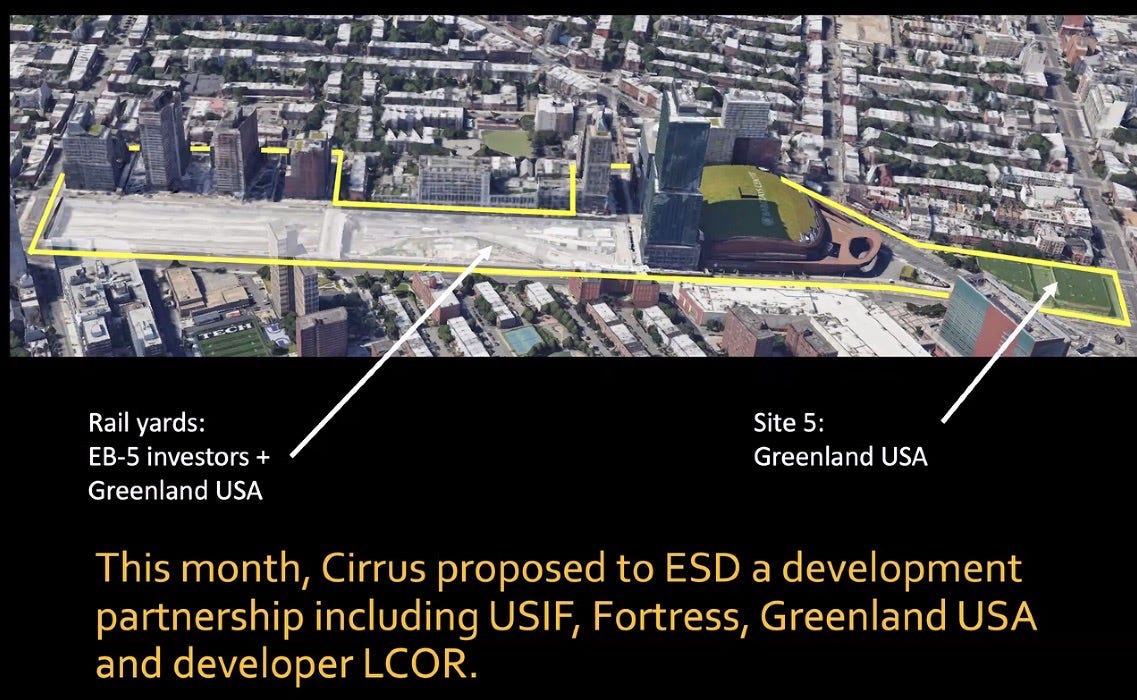

Enter LCOR

“This month, Cirrus proposed to ESD a development partnership” that includes the USIF, Fortress, Greenland USA, and LCOR, Veconi said last night. “This is a comparatively new development that just happened within the last week or so.”

Veconi, a member of the advisory Atlantic Yards Community Development Corporation (AY CDC), said he’d been informed by ESD when they announced a postponement of an AY CDC meeting originally scheduled for today—but never publicly announced.

That suggests ESD aimed to make an announcement before the May 31 deadline, paying at least lip service to the advisory body that was established in the 2014 settlement. At the AY CDC meeting in March, Veconi and Chair Daniel Kummer agreed that a meeting should be scheduled in April or May.

At that March meeting, an ESD executive, Joel Kolkmann, indicated that ESD would consider delaying the liquidated damages “if we were to receive something in the very near term,” involving “very clear milestones of what would have to happen,” as I reported for City Limits.

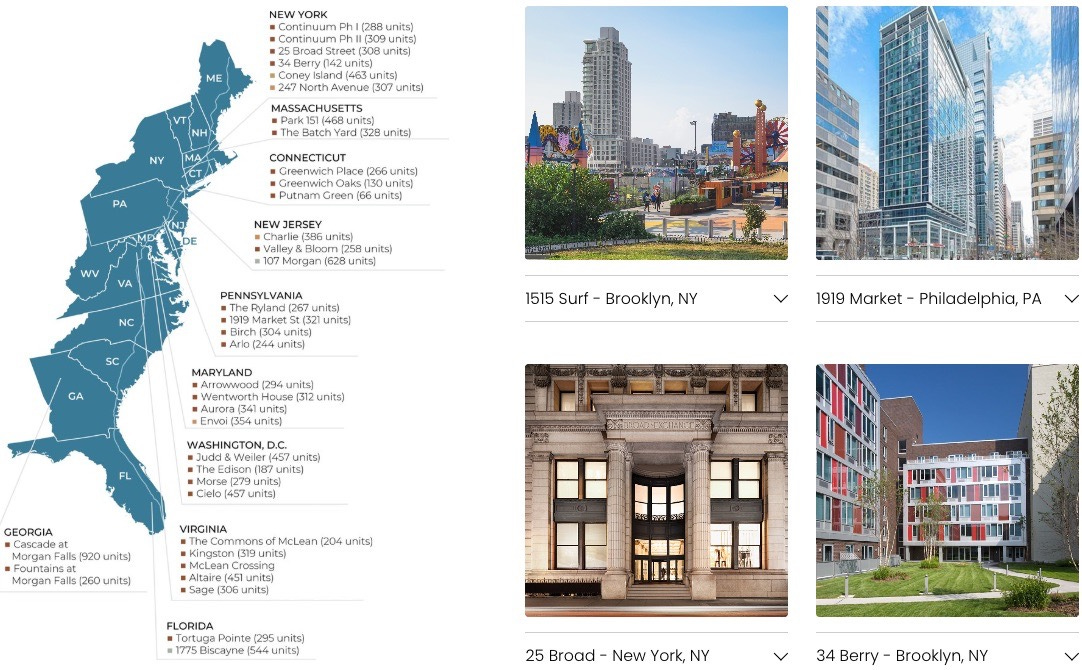

“With nearly 50 years of experience, LCOR is a vertically integrated multifamily developer and investment manager focused on the East Coast,” states LCOR, which has offices in Manhattan, Bethesda, MD, and Chesterbrook, PA.

LCOR, a multi-family development investment and operating company focused on the eastern United States, has apartment projects in Coney Island and Williamsburg, noted Veconi, but “it's not clear they've done a project of the scope of Atlantic Yards.”

It does claim a “Unique History of Public / Private Development,” involving the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and Nuclear Regulatory Commission Headquarters, as well as “one of the largest privately financed airport projects in history—JFK Terminal 4.” (Here’s an interview with David Sigman, Executive Vice President and Principal,)

What next?

Veconi offered more detail than ESD did in its statement, noting, “ESD is evaluating this proposal that's been made by Cirrus, and has asked that Cirrus receive approval from the MTA by June 30”—the MTA must permit platform work—”and present a plan for community engagement by August 31.”

As I’ve written, it’s hard to take “community engagement” seriously, since it has rarely significantly changed the project that the developer and government want, though it can provide the facade of consent and support.

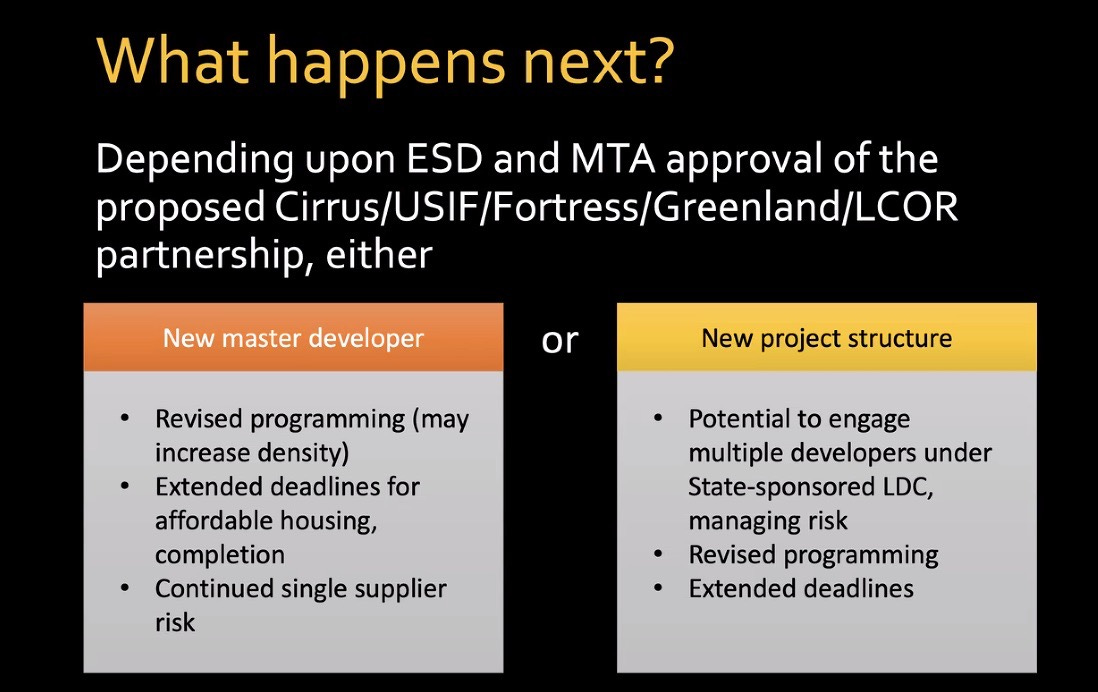

Veconi said the project may “continue to move forward under a master developer structure, where one developer is responsible for all construction with the right to sell individual lots to other developers,” a structure he noted carries significant risk.

If such a partnership either is not approved or doesn't hold together, he said, a new project structure might arise after ESD seeks liquidated damages from Greenland, which “may not have the ability to pay.” Veconi said BrooklynSpeaks favors a new structure as a lower-risk strategy.

Note: Cirrus Real Estate Managing Partner Joseph McDonnell declined to comment to Gothamist, referring questions to Empire State Development. (I’ve queried LCOR, as well.)

What about Greenland?

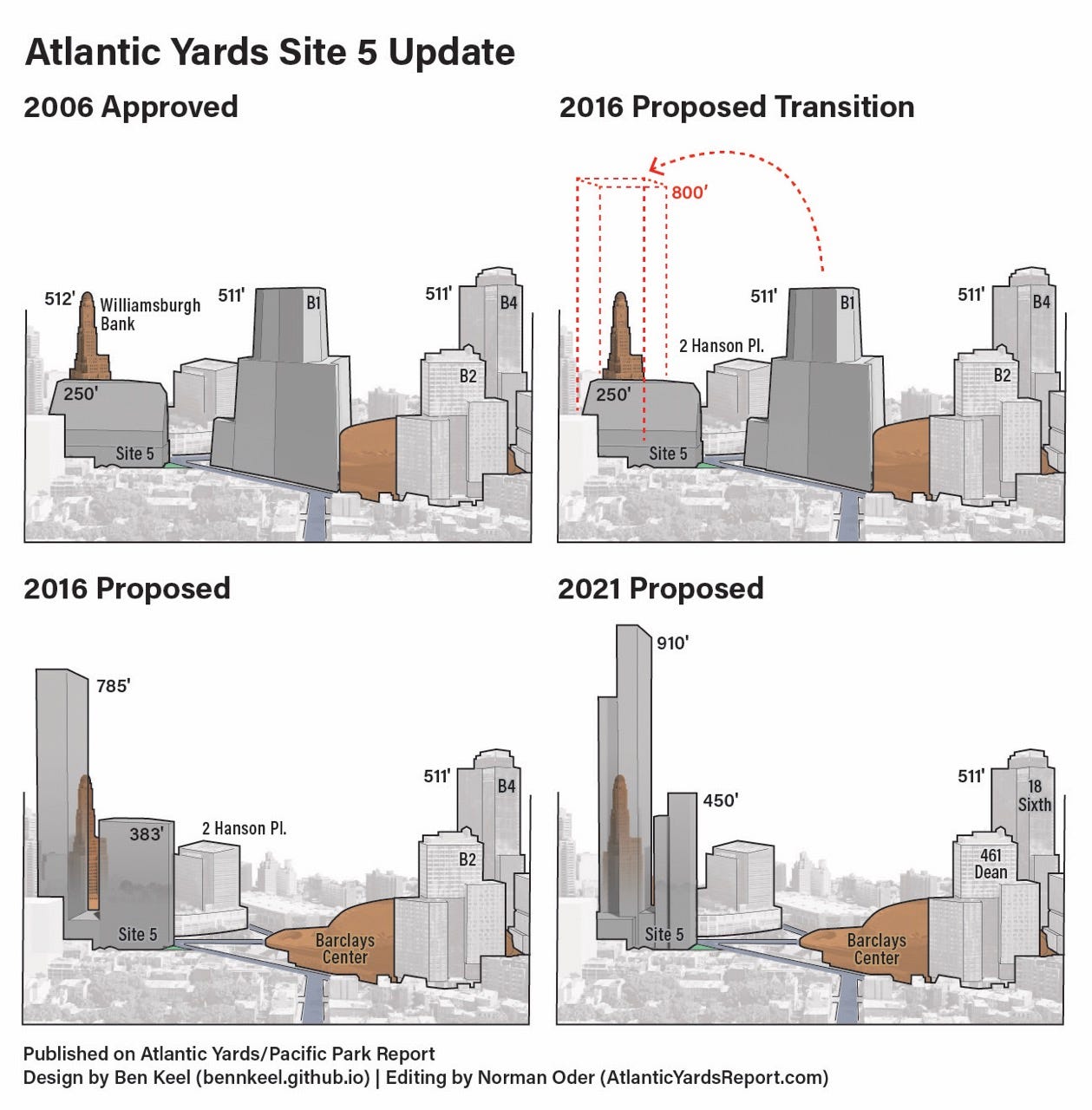

Would Greenland have the ability to pay the liquidated damages? While the Greenland affiliates that control the railyard sites may no longer have assets, the parent company still retains valuable real estate: the right to build a tower at Site 5, catercorner to the arena, and to build B1, a flagship tower looming over the arena.

Since 2015-16, Greenland has proposed shifting the bulk from B1, dubbed “Miss Brooklyn” by original architect Frank Gehry, across Flatbush Avenue to Site 5, creating a large, two-tower project.

In 2021, ESD signed an interim lease supporting a two-tower project with a taller tower rising 910 feet and a total of 1.242 million square feet, an unprecedented amount of bulk.

Greenland likely lacks the capacity to develop the site, but would partner with another developer or sell development rights, at least after gaining formal approval to shift the bulk.

Greenland’s stated role in the pending joint venture is unclear. Is it a nominal role to effectuate the foreclosure process? Does it mean the Site 5 project is included? If Greenland is allowed to extract value from its property, after failing to fulfill its promises, expect more pressure to collect the liquidated damages.

Expect an update at an AY CDC meeting “some time in the summer,” according to ESD.

New responsibilities

“Any modification of the plan must include meaningful community engagement and required public review,” Veconi said, noting that past key decisions “have been made behind closed doors.”

“This is something that's very, very important to address now, as well as previous failures in project oversight and quality of life management,” he said.

In a presentation last October, Veconi noted BrooklynSpeaks’ positions: future income-targeted apartments should be aimed at low-income tenants; the arena operators should pay for a publicly operated quality-of-life enforcement unit; and proposed project changes merit a third-party analysis of their financial feasibility.

I observed a potential tension between scale and affordability, suggested the arena operators—who’ve seen a huge rise in value—could be asked for even more; and third-party analyses might also address planning, design, and construction.

After all, the history of Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park has generated no small amount of distrust.

In sum, the "blight" of the railyards that supposedly needed to be remedied--the pretext for the whole fandango!--is still there. And not going anywhere anytime soon. Almost two decades after perfectly nice private homes and businesses were seized by the state and turned over to private developers.

Forget it, Jake. It's Chinatown.