Welcome to the Second Supplemental EIS! A $2M+ Contract for Consultant AKRF

Expect a judge-proof document easing project changes. Is there any funding for a civic response? Plus: some past bad predictions.

Let’s add another acronym to the jargon associated with Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park: an SSEIS, or Second Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement.

We encounter that rare acronym1 because such a study, a prelude for state approval of proposed project changes, was advanced at the Jan. 15 board meeting of Empire State Development (ESD), with the hiring of a key consultant.

The measure passed without discussion, as the video shows. ESD, a state authority focused on economic development, oversees/shepherds Atlantic Yards.

The ubiquitous environmental consultant AKRF will be hired again to “[p]rovide environmental consulting services including the preparation of environmental review documentation needed for compliance with the State Environmental Quality Review Act,” or SEQRA.

The two-year contract has two more potential one-year terms. The contract is not to exceed $2,167,000 ($1,588,500 base fee + reimbursables and $578,500 contingency).

Then again, AKRF contracts have a history of extensions. As of last August, the firm had been paid nearly $7.5 million, as I reported. The funding source is a “imprest account”—one regularly replenished—funded by the project developer.

New developers Cirrus Workforce Housing and LCOR must fund that account, succeeding Forest City Ratner, Greenland Forest City Partners, and Greenland USA.

Why it’s happening

The board materials presented to ESD Directors, who are appointed by the governor and follow the governor’s cue, noted that Atlantic Yards was the subject of a 2006 Final Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) and a 2014 Final Supplemental EIS (SEIS).

The Final EIS was required before initial approval of the project. Unmentioned: the Supplemental EIS was ordered after community groups sued; a judge agreed that ESD had not adequately studied the potential for project delays.

“It is anticipated that a Second Supplemental EIS (“SSEIS”) will be needed to consider proposed modifications to Phase II of the Project,” the ESD Board Materials say. “Environmental consulting services are needed to prepare the SSEIS.”

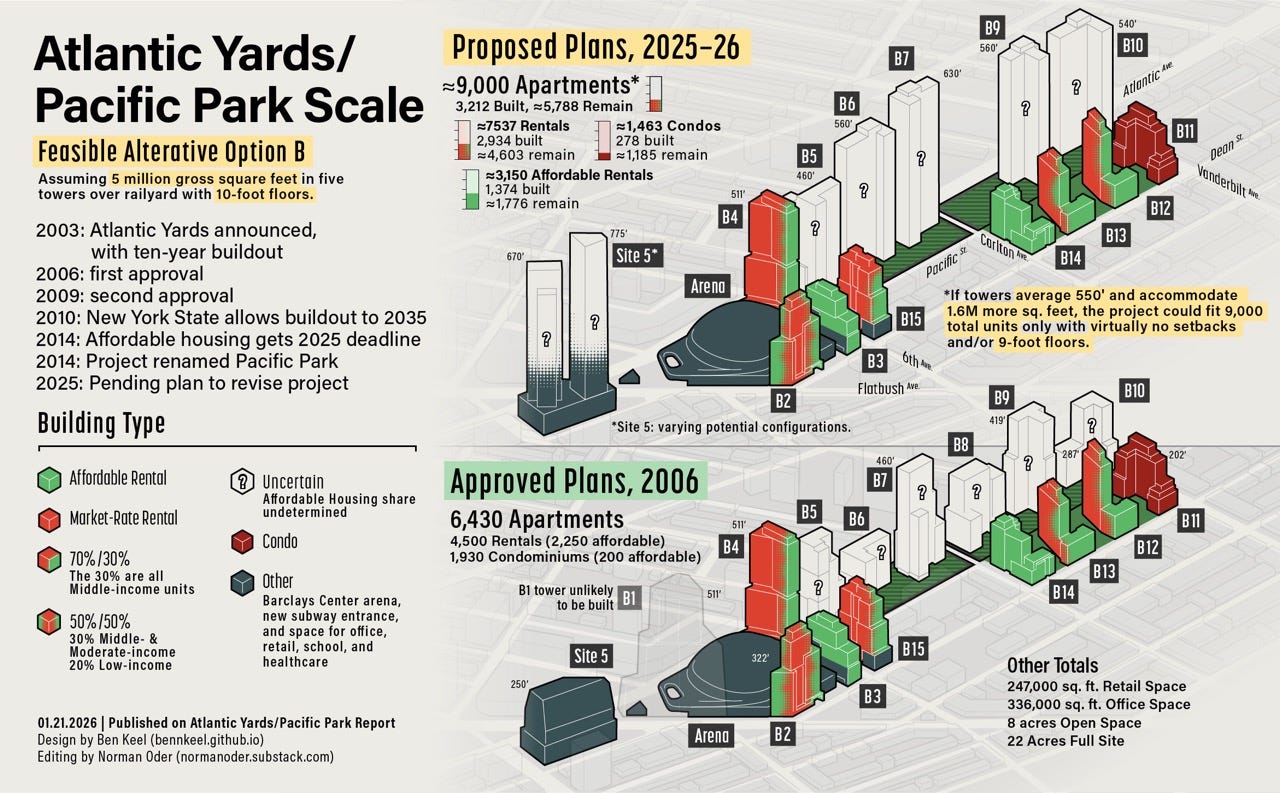

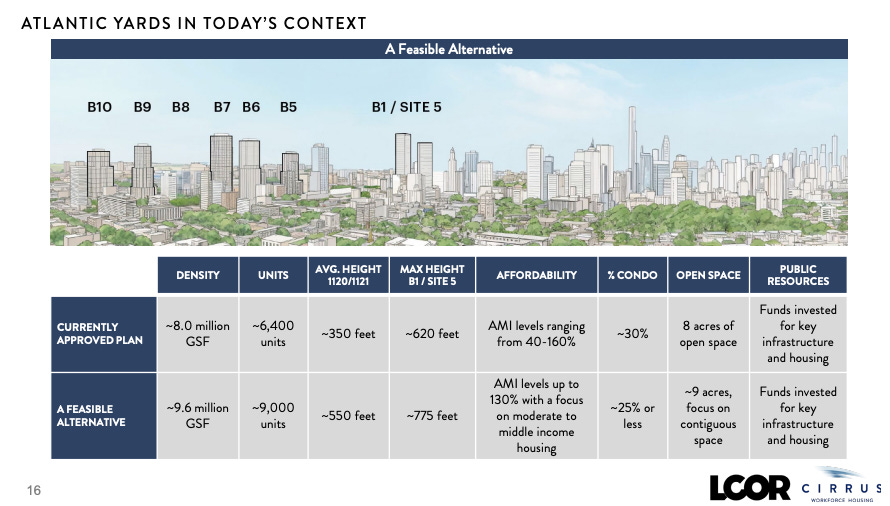

Translation: documents are required to ensure that the plan—a proposed increase from 6,430 to 9,000 apartments, with 1.6 million square feet, and attendant impacts from construction and operations—is credible enough to resist a legal challenge, with potential impacts studied and, if possible, mitigated.

A legally credible EIS faces a low judicial bar: “rational basis,” rather than preponderance of the evidence, the standard in civil cases. In other words, ESD needs a reason, not necessarily a convincing on.

So that’s enabled studies that don’t fully anticipate delays and the impact on promised benefits like affordable housing.

Or, as shown above—and discussed further below—even to anticipate the sequence of construction that the developers, as rational business people, might choose.

Any alternative?

That’s why, last August, I suggested that money be found for independent analyses of the project’s financial viability, scale, and community impact.

If the Consultants Have Earned $63.4M+, How About a Few Bucks For the Public?

Could there be an independent voice on the project's financial viability, scale, and community impact? After all, past independent reports have been credible.

If it can’t come from ESD—which has a budget for the (purportedly) advisory Atlantic Yards Community Development Corporation but simply apportions that to ESD staff—then it could come from city and state elected officials, with civic groups.

No competition for the job

The ESD board materials note that, though ESD solicited bids from three pre-qualified firms, only AKRF—which has previously done all such work on Atlantic Yards—submitted a proposal.

AKRF will prepare documents necessary for the project’s compliance with SEQRA, including :

Review of project materials

Coordination, strategy planning and meetings

Preparation of a Full Environmental Assessment Form, draft and final scope, Draft SSEIS, and Final SSEIS

Preparation for and participation in public reviews, including a public hearing

Memorandum of Environmental Commitments

Post-SEQRA approval support

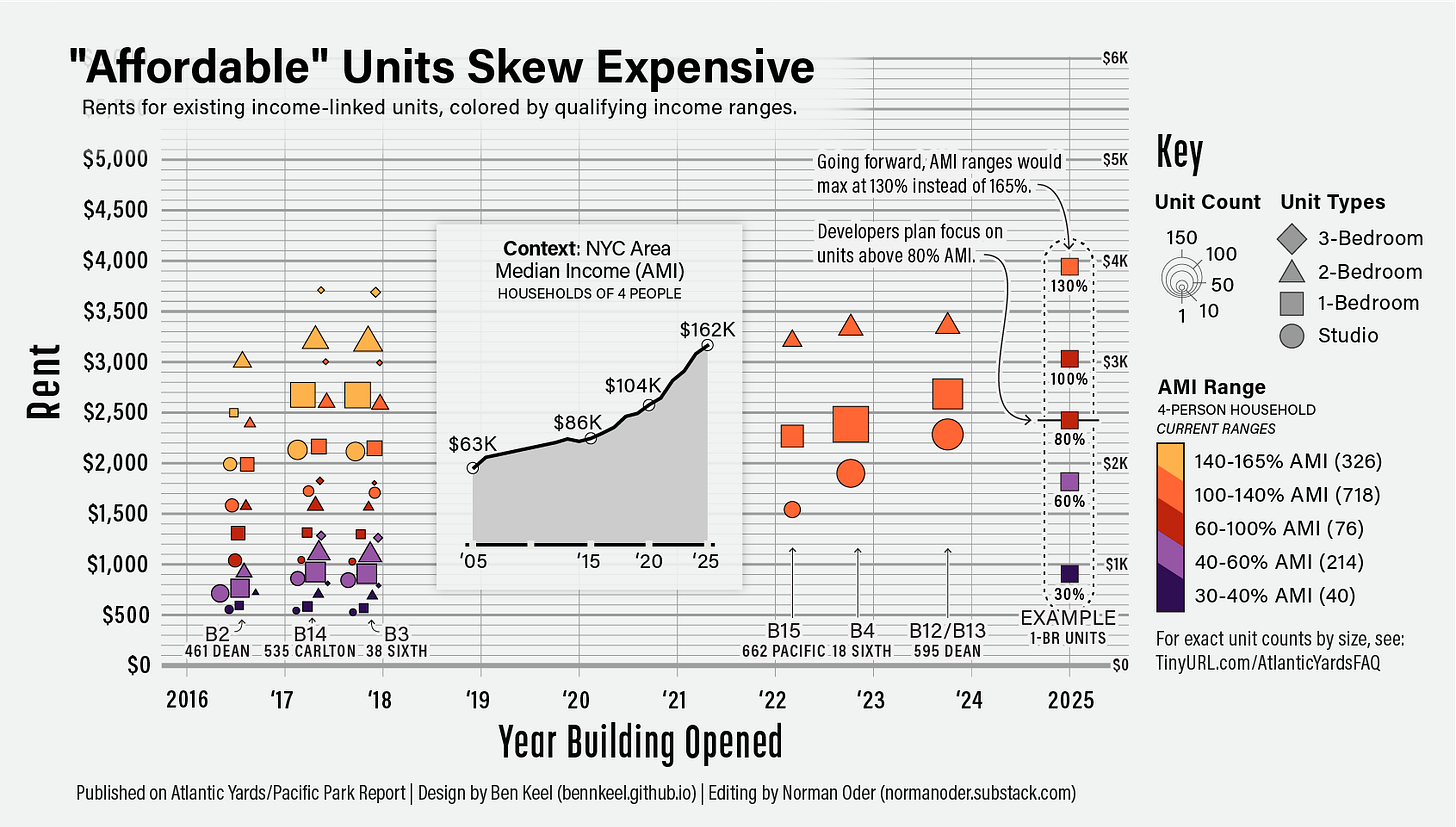

Perhaps AKRF will produce an official counterpart to the unofficial image below, given that it should have the proposed dimensions—height, floor plates, square footage—of the proposal.

If not, well, how is the public being informed?

AKRF background

AKRF describes itself:

Founded in 1981, AKRF is an award-winning consulting firm with over 400 planners, engineers, designers, economists, ecologists, geologists, historians, archaeologists, acousticians, and many other types of professionals guided by the belief that to be original is to be transformative.

It clearly has professional, competent people. But who do they answer to? Former lobbyist Richard Lipsky, at least when battling developers, called AKRF “trained in the abject aping of its master’s whims.”

AKRF on the spot?

At state oversight hearing in 2010, state Sen. Bill Perkins queried ESD General Counsel Anita Laremont about the use of blight, a rather malleable term, to further eminent domain. “Has AKRF ever found a situation in which there was no blight?” Perkins asked, provoking laughs.

Laremont said she couldn’t answer, then added, sternly, “AKRF does not find blight. Our board finds blight. AKRF does a study of neighborhood conditions and they give us the report.”

Not quite. The firm, as I’d discovered, was contracted to “prepare a blight study in support” of the proposed Atlantic Yards.

“Have you differed with their point of view?” Perkins asked.

“No,” Laremont acknowledged, but said courts had always accepted the blight findings. Rational basis.

AKRF on Atlantic Yards

AKRF has a page on Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park:

The redevelopment of a 22-acre underutilized area in Downtown Brooklyn is bringing a mix of uses and benefits to the local community.

That’s cautious phrasing: “bringing a mix of uses and benefits.” Alternatively, it could say, “has yet to bring many promised benefits.”

Either way, it’s a stretch to call the site Downtown Brooklyn. AKRF’s own document said the project site was “close to Downtown Brooklyn.”

The description:

The Atlantic Yards Arena and Redevelopment Project—for which AKRF prepared the SEQRA Environmental Impact Statement—includes the 18,000-seat Barclays Arena; 16 new commercial and residential buildings; a reconfigured LIRR train yard and subway facility upgrades; and eight acres of publicly accessible open space.

The $4.9 billion project includes up to 6,430 apartments, of which 2,250 will be affordable to low, moderate, and middle-income households.

It doesn’t say that the project is about half-complete, with the most complicated sites, requiring a platform over the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s Vanderbilt Yard, awaiting.

What AKRF did

AKRF describes its work on Atlantic Yards:

The EIS included complex interrelated quantitative analyses for multiple technical areas, including transportation, air quality, noise, and construction.

We also prepared detailed analyses of other areas of concern, such as historic resources, socioeconomics, land use and zoning compatibility, urban design and visual resources, and schools. Particular attention was paid to potential water quality impacts from combined sewer outfalls on the Gowanus Canal and East River.

We analyzed two phases of the project and two variations of the project program to allow for flexibility in the uses of three of the proposed buildings.

Comments on the DEIS [Draft EIS] were voluminous and AKRF worked around the clock with Empire State Development to effectively organize, evaluate, and respond to these comments in the FEIS within the narrow time frame allotted.

Well, not all comments. For example, they punted on the issue of crime.

More from AKRF:

AKRF prepared detailed analyses of the fiscal and economic impacts of the Atlantic Yards project, including an independent evaluation of revenue projections from arena events such as professional sports, concerts, and family shows along with their concession sales and community use.

We projected the direct and indirect economic activity that would result from the Brooklyn Nets’ basketball operations and other non-game events, including spending impacts in the neighborhood from arena visitors. AKRF also estimated the arena’s tax revenues to New York City, the MTA, and New York State from construction and operation of the full development program.

Wait a sec: wasn’t the full benefit of Atlantic Yards, in terms of tax revenues, predicated on office jobs that never arrived?

What happened next?

From AKRF:

Since the SEQRA Findings Statement was issued by ESD in 2006, AKRF prepared various technical memoranda and a Supplemental EIS to determine whether a delay in completion of Phase II of the project would result in new or materially different significant impacts as compared to the impacts identified in the 2006 FEIS.

That omits something: the Supplemental EIS was ordered by a judge after ESD—and, by extension, its contractor—failed to study the potential impacts of delay.

2006 completion prediction: 2016

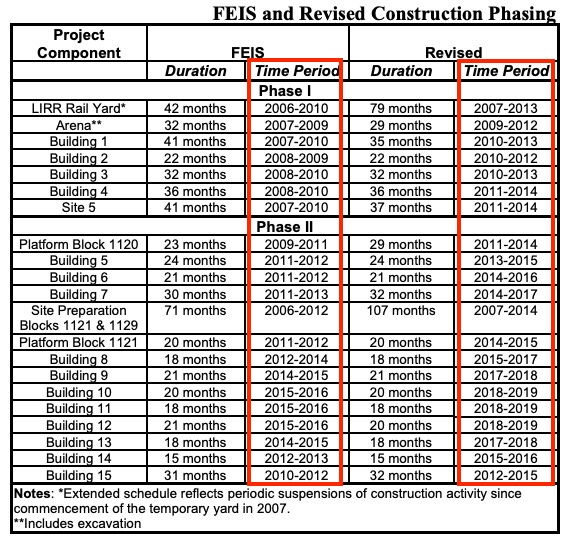

Let’s look at some past predictions regarding when Atlantic Yards might be completed. From the 2006 Final EIS Executive Summary:

If approved, the proposed arena and new subway entrance are expected to be completed by fall 2009 for opening day of the Nets 2009 season. Construction of the other buildings on the arena block and Site 5, as well as the improved rail yard, is expected to be completed by 2010. The entire proposed development is expected to be completed by 2016.

That Final EIS was accompanied by a 2006 Modified General Project Plan, setting out the contours of government requirements.

Instead, the recession and lawsuits delayed construction, prompting developer Bruce Ratner to renegotiate settled deals with ESD and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (ESD), leading to a 2009 Modified General Project Plan.

2009 completion prediction: 2019

No additional environmental review was required, ESD concluded. So there was no need for a Supplemental EIS, which, unmentioned, would’ve delayed the developer’s ability to sell arena bonds. After all, an EIS requires public hearings and responses to public questions.

Instead, ESD in June 2009 issued a Technical Memorandum, prepared by AKRF, suggesting that the first phase of the project would be completed in 2014, and the remainder by 2019—but also assessing the potential for a delay until 2024.

2010 completion sequence: railyard first?

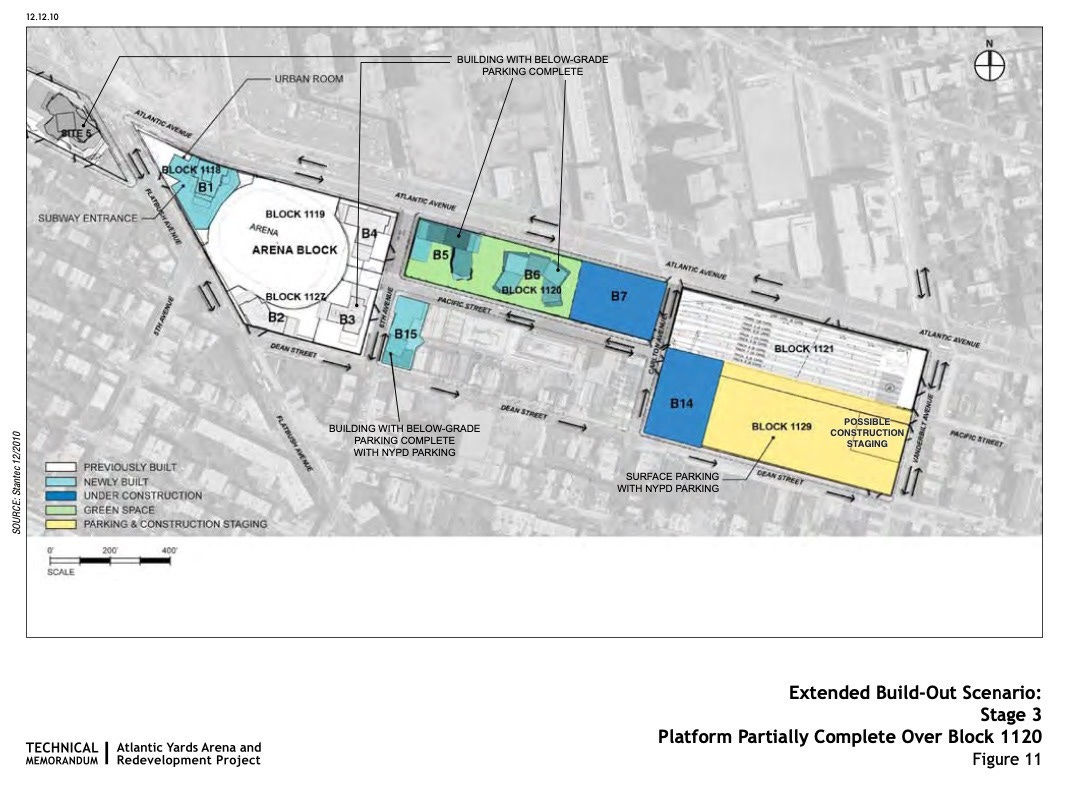

In response to a court order, ESD had AKRF produce a Technical Analysis to further make the case that no Supplemental EIS would be necessary, even with delays until 2035.

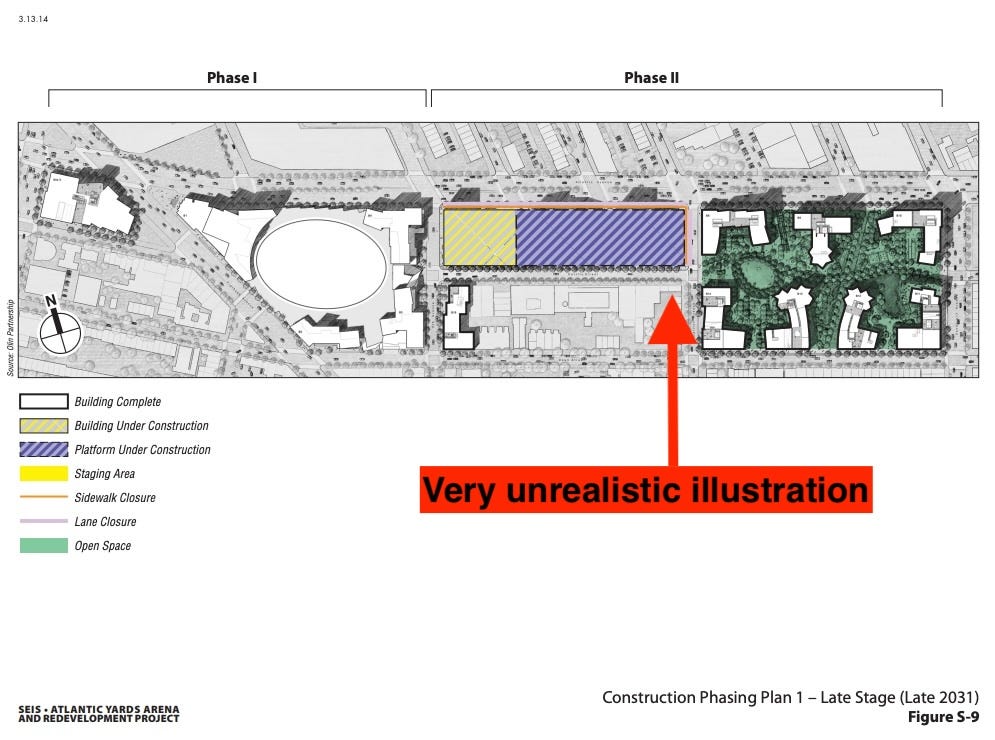

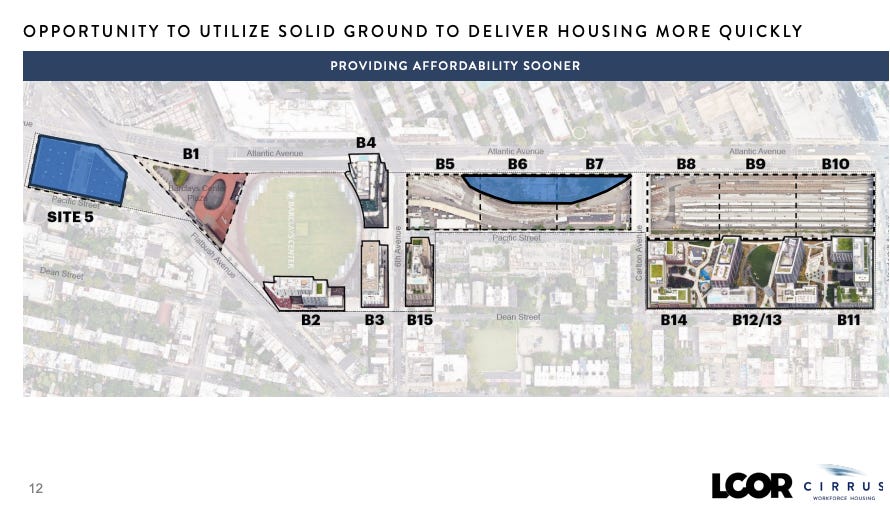

It’s somewhat risible, in retrospect, to see the illustrative construction sequence, which suggests that the railyard platform would be completed before construction on the southeast block, where terra firma makes it much easier to build.

These are supposed to be experts.

The cost of delay: displacement

The 2006 Final EIS waved off the likelihood that Atlantic Yards would cause residential displacement—residents forced out by gentrification—saying the “at-risk population” nearby was already decreasing.

“Second, similarities between the proposed project housing mix and the housing mix currently present in the ¾-mile study area indicate that the proposed project would not substantially change the socioeconomic profile of the study area,” the document states.

That carefully revised a previous claim that, though 84 percent of Atlantic Yards units would go to those earning more than the median household income nearby, the “socioeconomic profile” of new and existing households would be “comparable.”

Why’d they claim that? Because a roughly similar fraction would spend less than 30 percent of their income on housing. Of course, that ignored how current residents, earning less money, paid lower rent.

After my published critique, the Final EIS offered that “substantially change” hedge.

“Third, the project would introduce a substantial number of housing units to the study area, which could alleviate upward pressure on rental rates, reducing displacement pressures,” the Final EIS stated.

Well, that didn’t happen, especially given the lack of truly affordable units.

“Fourth, a majority of households identified as at-risk are located more than ½-mile from the project site, and there are intervening established residential communities with upward trends in property values and incomes, and active commercial corridors separating the project site from the at-risk population,” the document said.

That wasn’t much protection.

Displacement still dismissed in 2009 & 2010

The 2009 Technical Memorandum said that, despite delays, “the project’s potential for direct and indirect displacement… would remain the same as described” in the Final EIS.

The December 2010 Technical Analysis confirmed, “The potential for indirect displacement due to the Project would not be expected to increase with the Extended Build-Out Scenario,” citing existing trends.

“If there is a longer period before the Project is fully built,” it stated, “the number of at-risk households and businesses would continue to diminish as a result of trends unrelated to the Project.”

That’s pretty cold, since one justification for Atlantic Yards was to counter such trends by supplying below-market housing.

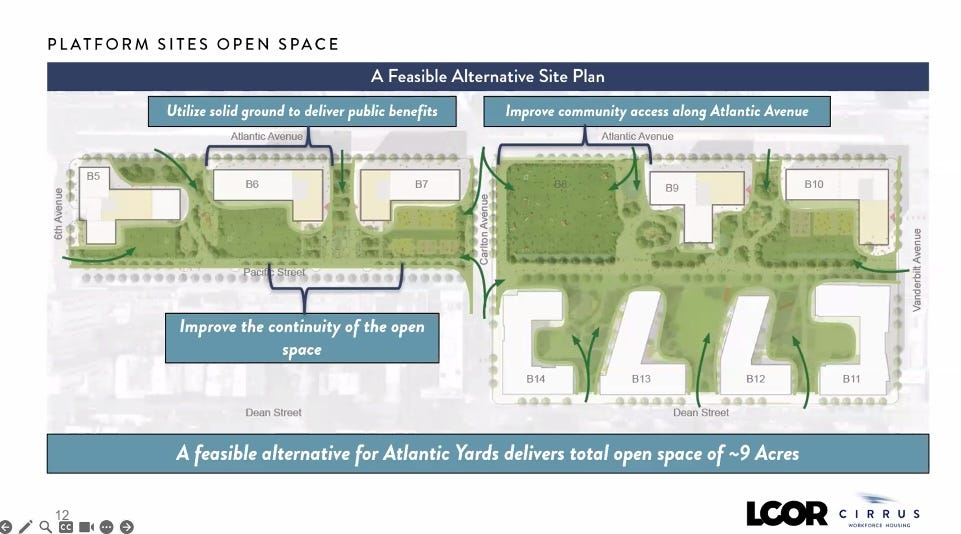

(So, will the upcoming SSEIS salute the new developers’ plans to deliver affordable housing relatively soon on terra firma, at least if they get the increase in bulk and subsidies/tax breaks they seek?)

What happened next?

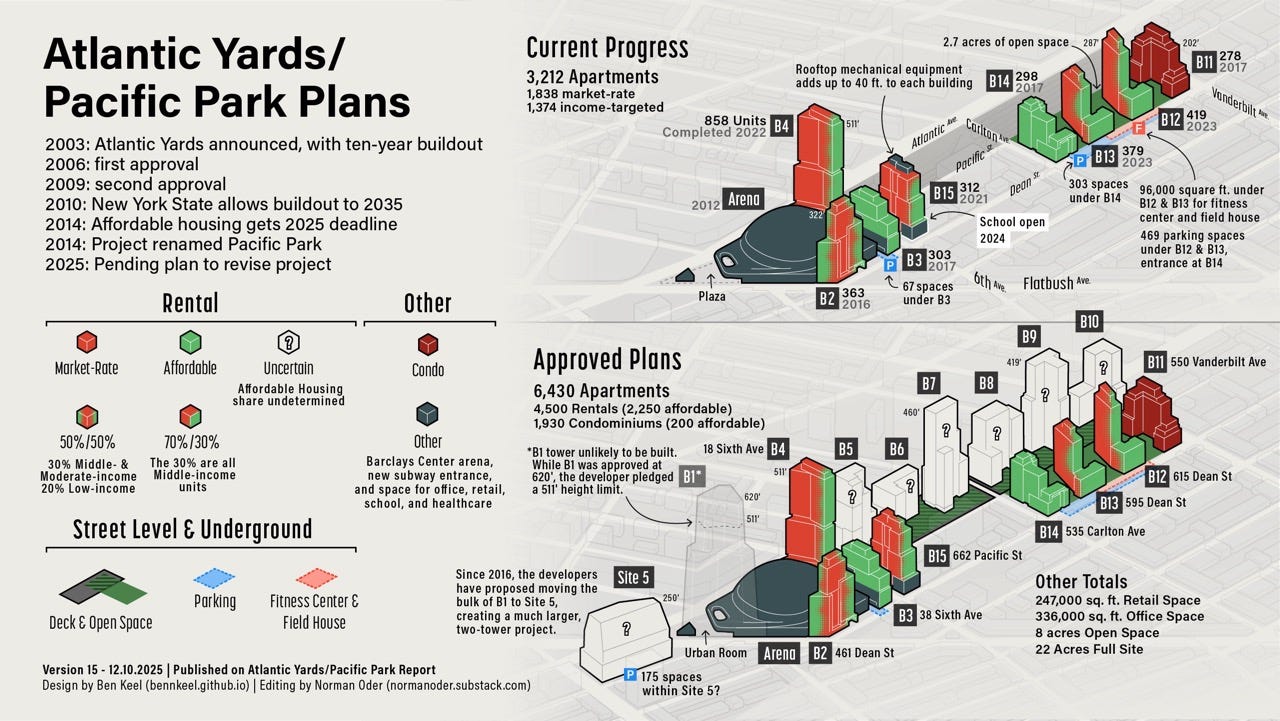

The Barclays Center opened in September 2012. The first tower, B2 (461 Dean St.) started construction in December 2012. Using innovative/risky modular construction techniques, B2 was supposed to take less than two years, but took nearly four years.

Before the arena opened, ruling in July 2011 on separately filed but combined lawsuits by BrooklynSpeaks and Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn, Supreme Court Justice Marcy Friedman concluded that ESD’s “use of the 10-year build date… lacked a rational basis,” and original developer Forest City Ratner hadn’t explained how it would complete the project.

She ordered a Supplemental EIS to assess expected delays, but limited that study to the project’s Phase 2, east of the arena block. AKRF describes its work:

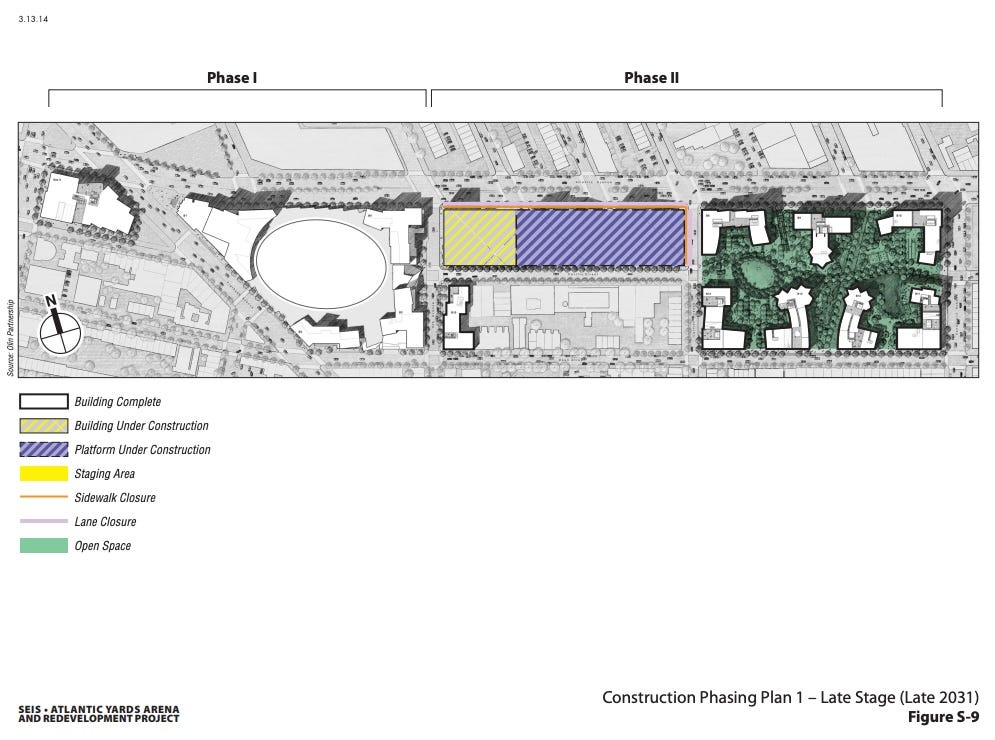

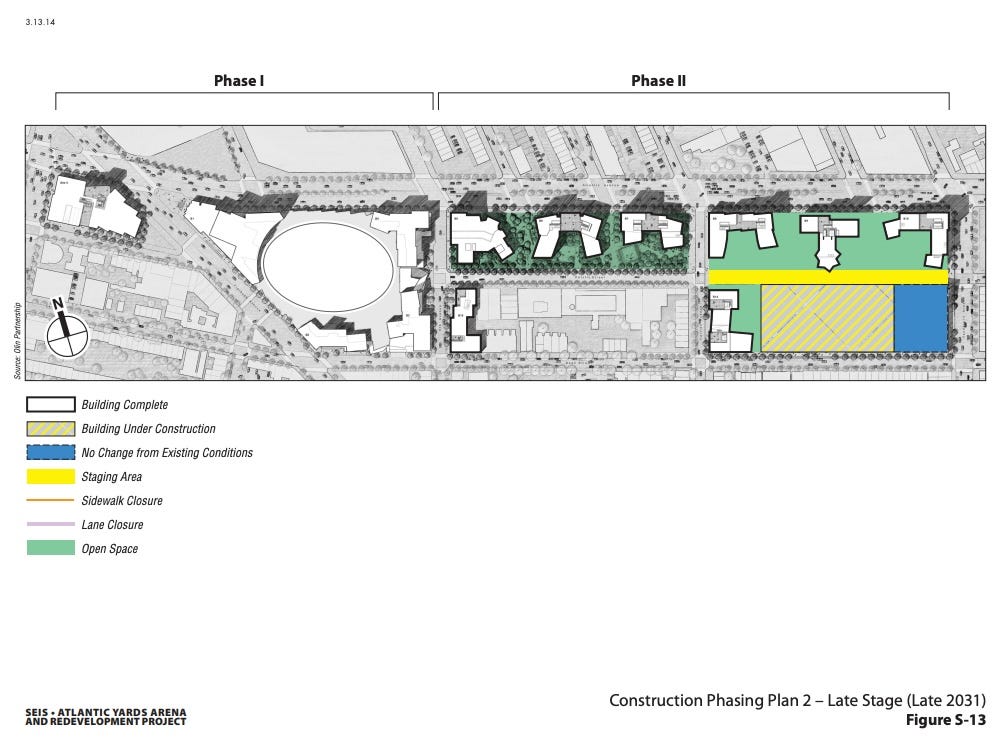

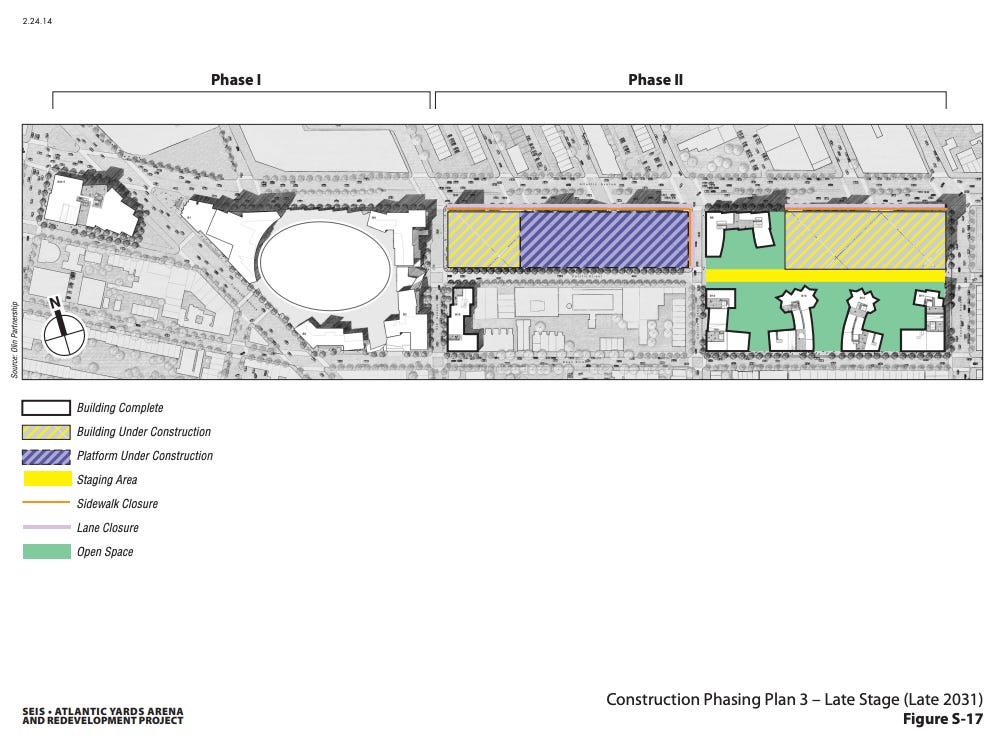

The SEIS included three hypothetical construction phasing plans that were intended to be illustrative of a reasonable range of construction sequences and schedules that may occur through the construction period, and to facilitate the identification of practicable measures to mitigate potential impacts. The SEIS was approved by ESD in 2014.

(Emphases added)

It’s remarkable that Construction Phasing Plan 1, below, assumed that, after the southeast block was constructed, the next towers would be built directly north, over the eastern railyard block, requiring a larger and more expensive platform than over the western one.

Meanwhile, Construction Phasing Plan 2 somehow assumed that the six towers over the railyard would be built over the expensive platform, before the low-hanging fruit on the southeast block.

Finally Construction Phasing Plan 3, while wisely portraying the southeast block as completed first, somehow assumed that the first tower built over the railyard would be on the more expensive eastern railyard block.

None of those sequences comport with reality—or the current plans. The new developers plan to build on the B6 and B7 sites first, on the railyard blocks, to take advantage of terra firma.

They even plan to eliminate the B8 tower—the only one over the railyard in the image immediately above— given the cost and complexity of building over an interchange.

Should we blame AKRF, or the developers whose plans they had to translate? Maybe both. One lesson from Atlantic Yards: expertise doesn’t always stand up to scrutiny.

Back to displacement

In 2014, the Final SEIS chapter on Socioeconomic Conditions continued to claim that the Project would not substantially change the area’s socioeconomic profile, in part because “the housing stock introduced by the Extended Build-Out Scenario would continue to be similar in tenure to the housing stock in the broader ¾-mile study area.”

Then again, “similar in tenure” simply means most would be rentals. It doesn’t mean similar in cost. But, presumably, it passes the “rational basis” test.

A little more fine print

“The FEIS identified a temporary significant adverse open space impact between the completion of Phase I and the completion of Phase II,” the 2009 Technical Memorandum stated.

“With the delayed build out scenario, this temporary impact would be extended, but would continue to be addressed by the Phase II completion of the 8 acres of publicly accessible open space.”

Well, “continue to be addressed” means it could take a while.

Today, the developers propose to eliminate the B8 tower and deliver a “transformative amenity,” an extra acre of open space.

No timing, though, has been suggested, and it likely would come toward the end of construction.

A Final SSEIS was prepared in 2024 by New York City for the Willets Point Phase 2 Development Project.

One of my favorite moments:

“Has AKRF ever found a situation in which there was no blight?” Perkins asked, provoking laughs.