Why Did Atlantic Yards Rescue Plan Run Aground? State Authorities Sought More Assurances

Developer Greenland USA sought to supersize towers and gain extensions, but officials were wary. MTA negotiations stalled. Shanghai-based executive even flew to NYC for meeting.

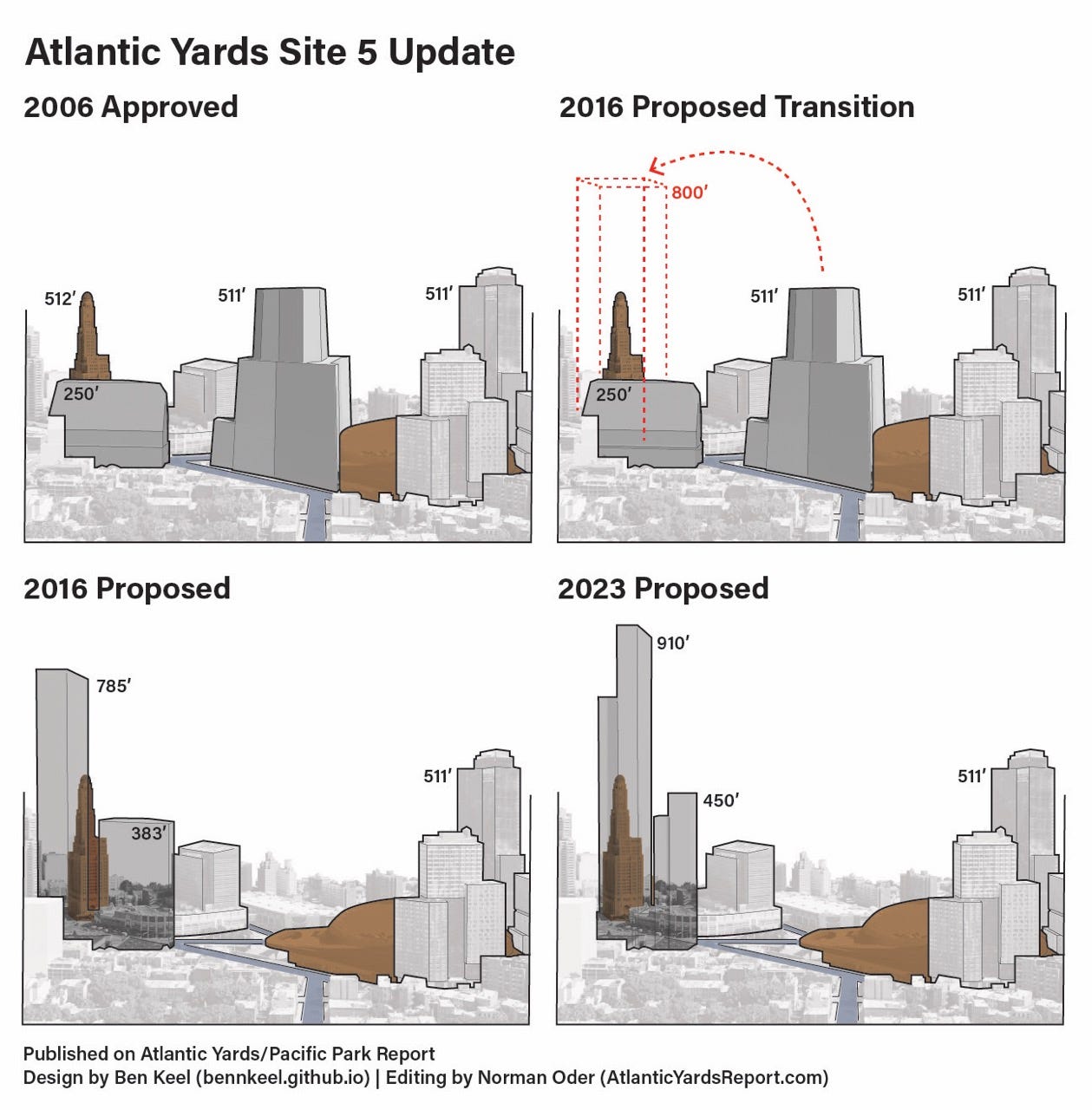

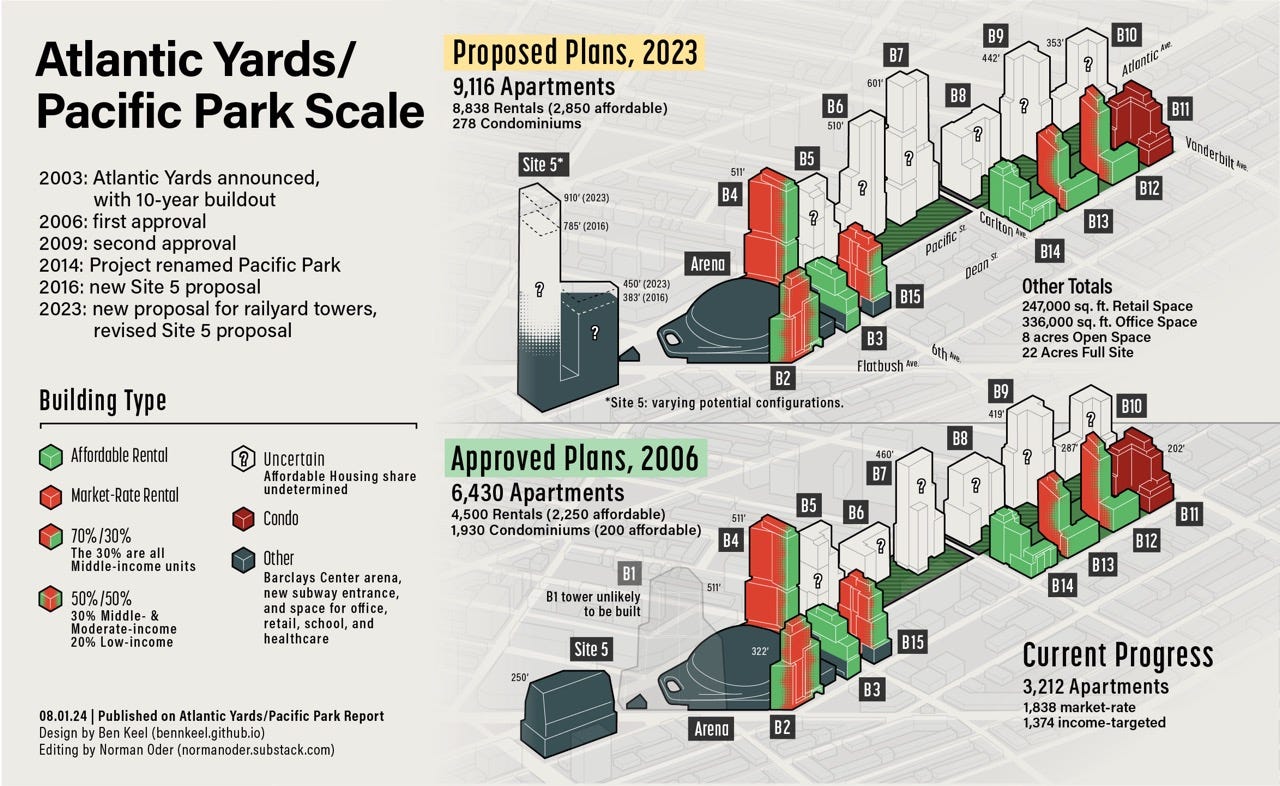

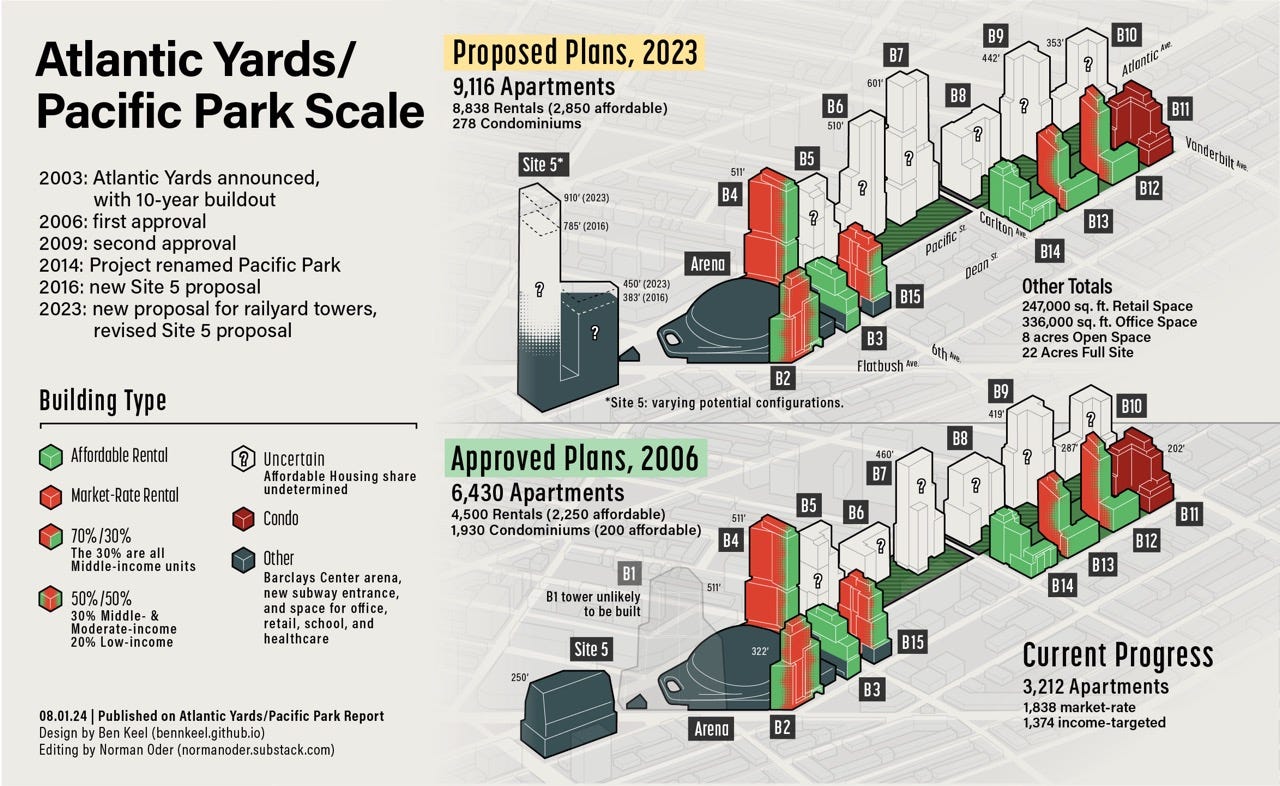

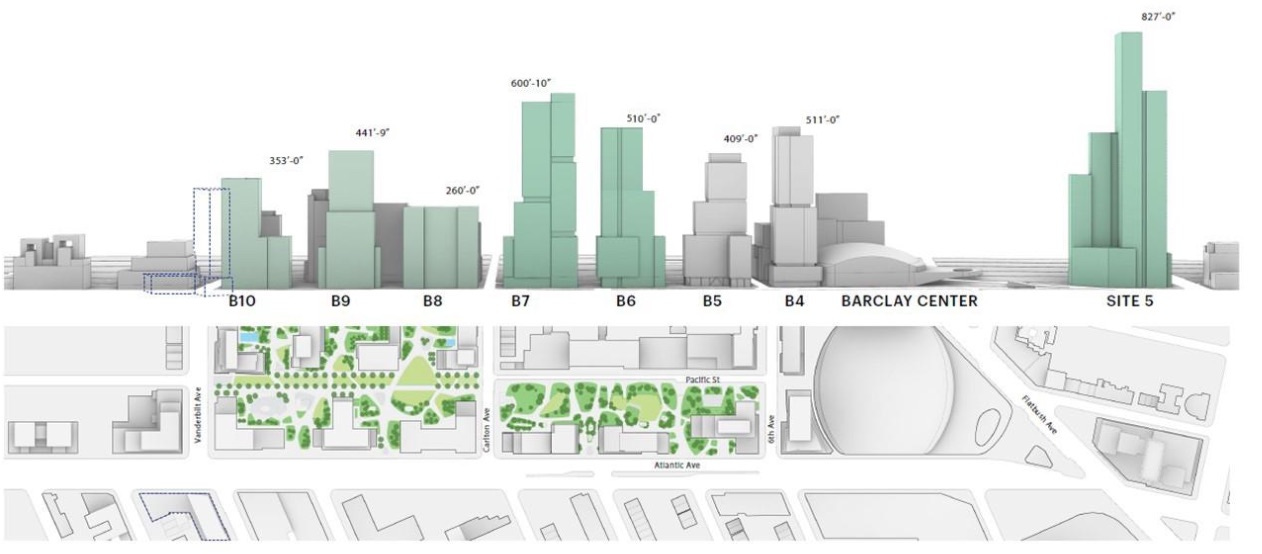

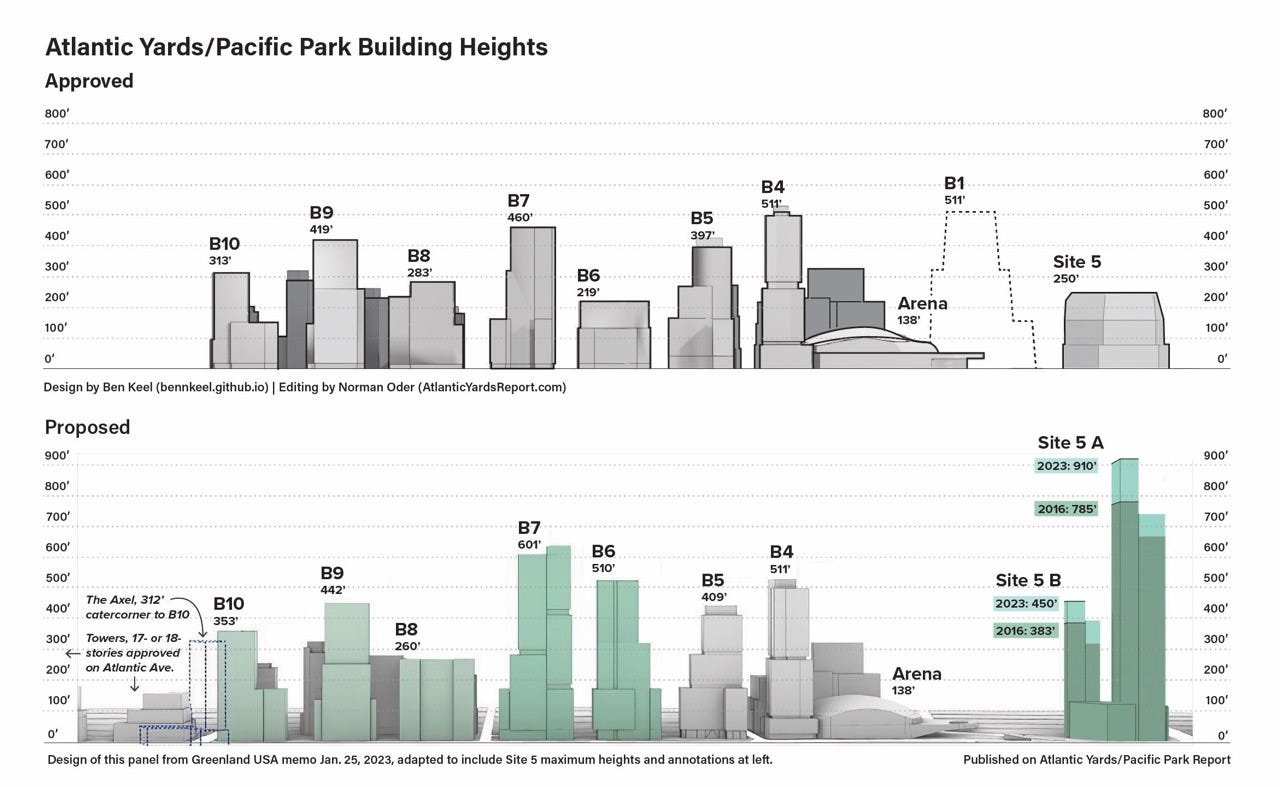

Part I, To Rescue Atlantic Yards, Developer Sought to Supersize Project, outlined the plans to expand Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park by adding 1 million square feet to six towers over the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s Vanderbilt Yard, and enlarging the two-tower project long proposed at Site 5, catercorner to the arena.

New documents help flesh out a confusing public record, which suggested partial progress on Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park as the decade began, then stasis, with little explanation from either the developer or government officials before rights to six railyard development sites went into foreclosure last November.

As reported, Empire State Development (ESD), the state authority that oversees/shepherds the project, was somewhat supportive of developer Greenland USA’s plan to rescue the project by supersizing it.

ESD, however, wanted more assurances from Greenland, such as the involvement of a local partner. Meanwhile, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) and Greenland jousted over assurances regarding work on the platform.

Greenland, buffeted by financial losses, saw urgency as interest rates rose and a key tax break expired. Though it and public agencies came closer to a deal, they couldn’t get it done and stave off Greenland’s pending loss of six sites via a foreclosure auction.

Initial optimism

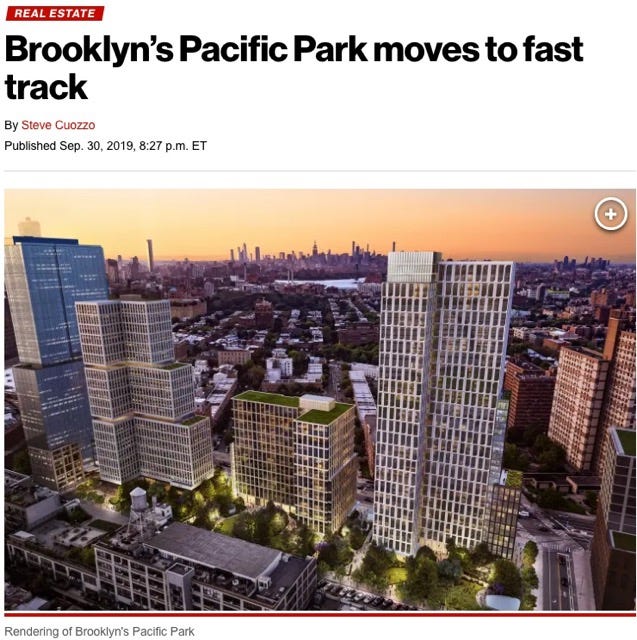

Greenland had once seemed optimistic, saying in the Sept. 30, 2019 New York Post that it planned to start the platform in 2020. But the pandemic intervened, and work didn’t start.

On March 24, 2020, the developer asked ESD to extend project deadlines, citing COVID. Such an extension would remain a point of contention.

Greenland also was slowed by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), which, on April 6, 2020, announced a “Railroad Emergency,” likely pandemic-related, delaying their ability to review the developer’s plans for the platform.

(This article is based significantly on documents received from Empire State Development thanks to a Freedom of Information Law request. The documents, of course, cannot tell the full story, as there may been conversations or other exchanges not shared with me.)

Possible progress

Still, in a May 6, 2020 memo predicting planned Atlantic Yards work for the second half of the year, Greenland pronounced, without hedging, "Platform construction will commence."

That construction didn’t happen, given lack of MTA approvals, but another track suggested progress. On Oct. 25, 2021, ESD signed an Interim Lease with the Greenland subsidiary developing Site 5, the parcel catercorner to the arena slated for a giant two-tower project.

Greenland updated its plans, first floated in 2015-16, to transfer bulk from the project’s unbuilt flagship tower, B1 (aka “Miss Brooklyn”), once planned to loom over the arena. Below is a very unofficial rendering.

The lease’s Exhibit K detailed a project with 1.242 million square feet, with one tower 910’ and the other 450’. A large hotel and dynamic LED signage would be permitted, along with below-grade retail, while parking would be eliminated.

That process didn’t start, apparently because ESD, unwilling to simply let Greenland monetize that Site 5 parcel, first wanted clarity on the developer’s commitment to the platform and six railyard towers.

The platform, again

In early 2022, Greenland was told the MTA was ready to permit platform construction, but with conditions.

Publicly, the developer seemed optimistic. In May 2022, Greenland USA VP Scott Solish described, at a public meeting, the developer’s plan to commence platform work on the first of the two railyard blocks: Block 1120, bounded by Sixth and Carlton avenues and Atlantic Avenue and Pacific Street.

The announcement included granular plans for fencing and traffic changes, as shown above.

Greenland, a subsidiary of a Shanghai-based company, already had contractors in place, later revealed as China Construction America and its subsidiary Plaza Construction.

Blaming the state

A stall continued. Greenland blamed the state, charging in a Nov. 21, 2022 letter, “the MTA Parties… continue to create unreasonably onerous requirements” that exceeded previous agreements.

The developer also noted that, three months earlier, it had sought to “move forward with this critical re-imagining of Site 5 and the Pacific Park project,” But “Greenland is still awaiting a substantive response from ESD.”

No housing subsidies?

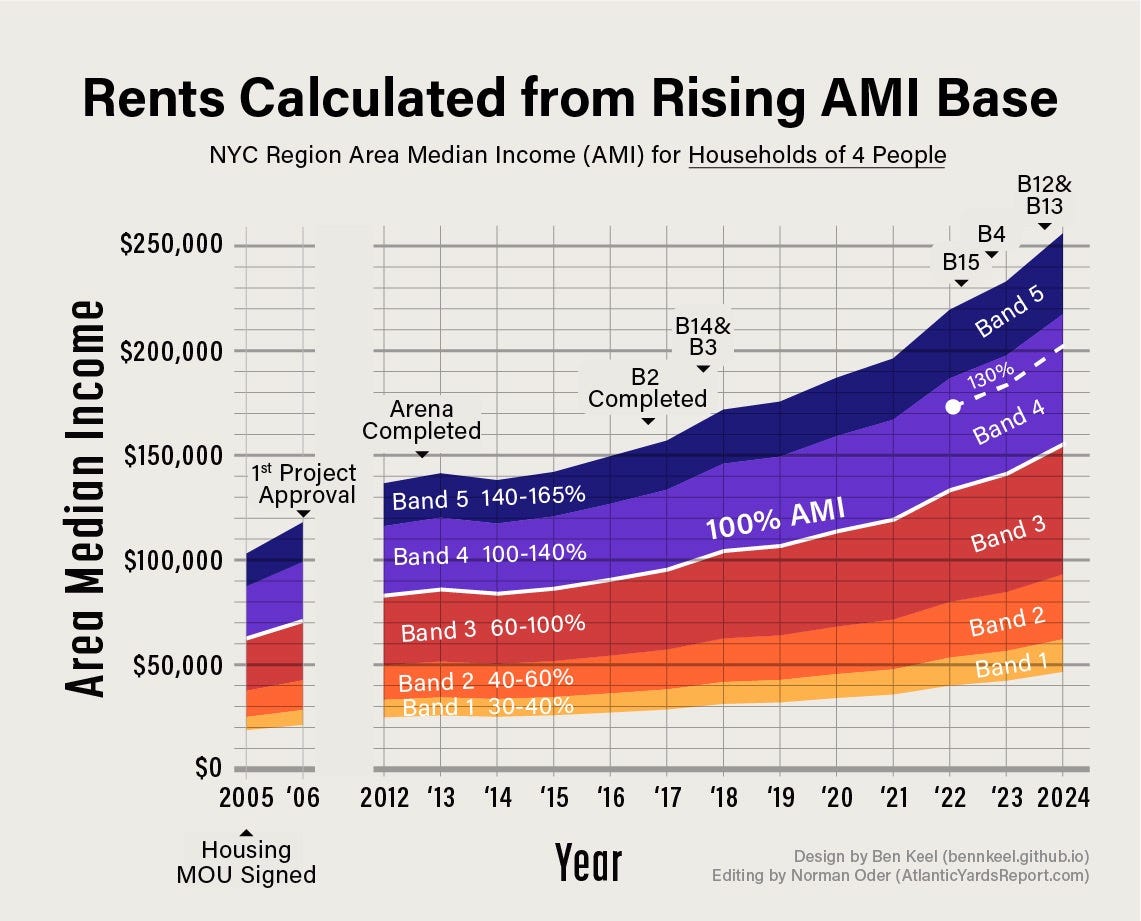

Greenland lamented the lack of additional housing subsidies, stating that “senior development executives” at city and state housing agencies wouldn’t help finance the first three railyard towers, given their focus on 100% affordable projects targeted to “very low income” or “extremely low income” households.

Such buildings would not be viable in Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park, Greenland contended, given the cost of the platform and established plans for mixed-income buildings.

In an Oct. 28, 2019 email, after Greenland’s New York Post announcement of platform plans, Solish had asked the New York City Housing Development Corporation (HDC) about “HDC possible interest” in helping fund the first three railyard towers.

“They are large buildings,” he wrote, “and we would be very interested in targeting lower [income levels] through possible bond financing for late 2020 or early 2021 commencements.”

A week later, Greenland Senior Development Manager Lemore Czeisler asked HDC if they had a colleague at their counterpart state agency, the Division of Housing and Community Renewal “that we can call to verify that their position is the same and that tax credits, and tax exempt debt is being reserved for low and very low income units only.”

The response was unclear, as the state housing agency, unlike the city one, did not deliver any documents in response to my Freedom of Information Law request.

Still, it’s possible that, without the pandemic and other platform delays, Greenland might have taken advantage of the 421-a tax break, which would’ve required construction to start by June 2022.

While the program, known as Affordable New York, was most commonly used to finance buildings with only middle-income affordable units, as with the four most recent Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park towers (see graphic above; not 130% of AMI), it had options for some lower-income units.

Notice of delays

In his Nov. 21, 2022 letter to state and city officials, Greenland USA president Gang Hu cited the developer as “the driving force that rescued a stalled project” in 2014 when it entered as majority partner. But the project’s next phases were “imperiled” by the expiration of 421-a, the lack of housing subsidies, MTA delays, and “ESD's unwillingness” to enact the changes to expand the Site 5 plan.

That came on top of pandemic-related impacts, Site 5 delays caused by litigation from P.C. Richard, and soil conditions that required re-engineering of platform foundations.

All told, Hu wrote, the delays “put the next phases of Pacific Park on indefinite hold and jeopardize its long-term feasibility.” Unmentioned: the firm’s parent, Greenland Holding Group, had also been struggling domestically, as its credit rating dropped.

New help sought

Greenland sought succor. Citing the expiring tax break and the housing agencies’ policies, Hu announced an Affordable Housing Subsidy Unavailability per the project’s Development Agreement, the 2010 contract between developer and state.

Also, he wrote, the MTA’s posture and “the inter-connectivity of the Development Agreement and the Platform Agreement” resulted in an Unavoidable Delay. A similar delay, Greenland said, was triggered by ESD’s foot-dragging on Site 5.

Thus Greenland sought to extend the project’s 2035 Outside Completion Date—25 years after the May 12, 2010 Effective Date—and 2025 affordable housing obligations. That would delay the $2,000/month fines, as established in 2014, for each of the project’s remaining 876 affordable housing units (of 2,250 required) not built by a May 2025 deadline.

Greenland also requested a “targeted tax incentive program [to] replace and mirror” the 421-a tax break, ensuring project financing.

Regarding MTA work, it sought “allocation of available capital funding”—implying public subsidy for the platform, which could easily cost more than $300 million.

A bigger project

Two months later, after a Greenland-ESD meeting, a Jan. 26, 2023 letter from executive Solish to ESD implied cordial cooperation, as discussed in Part 1.

As Greenland proposed it, the process to transfer development rights from the unbuilt flagship tower, once slated to loom over the arena, to Site 5 would begin immediately and include outreach to elected officials. A “planning facilitator” would solicit community feedback regarding Site 5 and the plan for larger railyard towers.

ESD was expected to provide a 421-a equivalent via a PILOT (payment in lieu of taxes) program, as was later enacted for developments in rezoned Gowanus. The developer projected that 25% of future rental housing would be affordable. That meant 600 more affordable units, albeit over an extended timeline.

However, Greenland’s Solish, a veteran of the New York City Economic Development Corporation and the firm’s only public-facing staffer with local expertise, soon left his position. That left Greenland USA President Hu to write Kathryn Garcia, Director of State Operations, on March 20, 2023 to urge cooperation.

If state officials could commit to timely tax benefits and project modifications, wrote Hu, Greenland could then ally with “potential development partners with expertise in local development and community relations” to complete the project.

ESD pushes back

Responding April 10, 2023, ESD’s Arden Sokolow, Executive VP, Real Estate, was only partly encouraging, wanting Greenland to show more commitment. Before ESD moved forward, she wrote, Greenland would have to “fully resolve” outstanding issues with the MTA regarding the platform.

Moreover, Greenland, which entered the project with original developer Forest City Ratner as their local partner, would have to identify a new partner with a local track record. It also had to provide ESD “a detailed analysis of the financial feasibility and sources and uses” of project funds.

As noted in Part 1, Sokolow saw Site 5 approvals linked to the developer’s commitment to build the railyard towers and deliver the project’s required affordable housing.

In a separate letter, ESD pushed back, denying Greenland’s claims of Unavoidable Delay and Affordable Housing Subsidy Unavailability, saying the developer had not substantiated them, as required, within 20 days.

Moreover, ESD contended, an Affordable Housing Subsidy Unavailability couldn’t apply to the project’s Phase 2. Regarding the MTA, there was no Unavoidable Delay, wrote Sokolow, because that definition “expressly carves out the inability to ‘obtain or timely obtain any Approvals.’”

Murky in public

Publicly, all seemed murky. At an April 11, 2023 meeting of the advisory Atlantic Yards Community Development Corporation (AY CDC), ESD’s Atlantic Yards project manager Tobi Jaiyesimi said the developer was still negotiating with the MTA regarding the platform. Soon Jaiyesimi would leave, without an immediate replacement.

At that meeting, AY CDC Director Gib Veconi asked if ESD had “done an independent analysis” to assess whether it was viable for a private developer to deck the railyard, under the plan approved.

Jaiyesimi said no. Unmentioned: ESD already knew that Greenland’s proposal to expand the project suggested the existing plan was not viable.

Veconi suggested that railyard development might not proceed if privately financed, “and we might need to see if there's an opportunity for some type of other subsidy." (If any increased subsidy is discussed, shouldn’t it deliver reciprocal public benefit or public ownership?)

Greenland disagrees

Responding on April 27 to ESD’s letter, Greenland disagreed strongly. It contended that its November 2022 letter sufficiently substantiated the Affordable Housing Subsidy Unavailability and Unavoidable Delay.

Moreover, Greenland said ESD was wrong to claim that the Affordable Housing Subsidy Unavailability was inapplicable to Phase 2, citing Section 8.7 of the Development Agreement. Indeed, that does refer to Phase 2 Construction.

However, the Development Agreement requires the developer to apply to government agencies before claiming a Subsidy Unavailability, so it’s unclear if that concept encompasses the failure of current programs to fit the project’s goals.

As to the MTA impasse, Greenland contended that the MTA requirements were not Approvals, defining that as “are licenses and other permits from Governmental Authorities in the context of such entities performing a governmental function in applying Requirements.” (The concept also encompasses “consents” and “authorizations.”)

Regarding Site 5, Greenland noted that it had agreed, on ESD’s advice, to settle litigation from P.C. Richard, which claimed it had been promised a place in the future development. (That should’ve been paid for by Forest City, though.)

After the Site 5 Interim Lease was signed, Greenland expected progress. Instead, Greenland was “troubled” that ESD had applied new preconditions.

Possible progress

The two parties stayed in touch. After a meeting May 12, Greenland’s Macy Wang re-sent ESD the proposal it had provided in January outlining project changes. The state authority was at least partly on board.

Four days later, Joel Kolkmann, ESD’s senior VP of real estate and planning, shared with Greenland a draft solicitation for “Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park Public Meeting Facilitation Services,” scheduled to begin in the fall of 2023, to gather public input.

Such a program might recur as the project re-emerges. Then again, with 50 to 100 people expected at each meeting, according to the draft, it might be tough to discern community visions, which presumably would be shaped by the presentation itself.

The ESD draft did not mention a 2018 proposal by Jaime Stein, then a member of the AY CDC, that the advisory Board hire its own planning, design, and construction consultants—not merely facilitators—to review the Site 5 proposal to inform the board and the public. (As of 2018, the plan for expanded railyard towers had not emerged.)

Greenland pleads

Greenland felt pressure, perhaps because it saw the looming EB-5 debt, pointing toward foreclosure. On May 26, 2023, Greenland’s Hu wrote to Gov. Kathy Hochul, sounding both desperate and potentially litigious.

“MTA’s unreasonable requirements” regarding “the Platform project have resulted in damages to Greenland,” he wrote. He acknowledged “encouraging progress,” as Greenland had agreed to post a $180 million letter of credit with the MTA "and to pay the air right [sic] purchase price for Platform Block 1120”—between Sixth and Carlton avenues—in one installment.”

That latter wasn’t too much of a commitment, since a June 1, 2023 payment would’ve reached a cumulative $96 million and paid for Block 1120 development rights.

However, Hu wrote, MTA’s request for an additional bond was “unreasonably duplicative,” since, among other things, the $180 million letter of credit already “represents 1.18 times of the development cost of the Platform.”

It’s unclear how much the MTA requested for an additional bond, but I suspect that an 18% overage is cutting it close.

Hu’s framing implies that the first platform phase would cost $152.5 million. The second phase, which requires more extensive construction, surely would cost more, since there’s no terra firma jutting south into the railyard from Atlantic Avenue.

Hu also wrote that delays, as noted in Part 1, scotched a plan to sell railyard development rights to another developer —could that be Related?—which caused Greenland “substantial” losses.

Also, Greenland faced delays, without a 421-a substitute. So he asked MTA for an additional concession: “to allow us to suspend the payment of the upcoming annual air rights payment,” the $11 million due by June.

It’s unclear if Hu’s message got a response from the Governor, but Greenland did make that June 2023 payment, but not the 2024 one.

Escalating issues

ESD on July 6, 2023 responded curtly to Greenland’s April 27 letter. ESD’s Sokolow reiterated that Greenland had not substantiated the asserted Affordable Housing Subsidy Unavailability and Unavoidable Delay.

Greenland, apparently alarmed, pushed for a higher-level meeting, flying its Shanghai-based Chairman, Yuliang Zhang, to New York, to meet with Garcia and others on July 25, apparently arranged by the firm’s lobbyists at Kasirer.

They did not reach a resolution. However, some progress seemed evident.

At an Aug. 2, 2023 meeting of the AY CDC, the advisory group members were told that the MTA and Greenland had resolved disputes related to the platform. While Greenland had agreed to provide the required bond, it “is not in our hands yet,” said MTA executive Robair Reichenstein. (It’s not clear if that referenced the additional requirements that Greenland deemed excessive.)

Kolkman said ESD had gotten responses to its solicitation for a community consultant to convene meetings regarding the project’s future. He did not, however, disclose Greenland’s aim to supersize the railyard towers and Site 5, Nor did that community consultation process start.

Greenland hedged when asked when the platform’s first phase, expected to last three years, would start. An executive cited the lack of the 421-a tax break, but not the tensions with state agencies. ESD confirmed that a 421-a substitute, via payments in lieu of taxes (PILOTs) was being considered.

“With the beginning of the public engagement that ESD is going to lead, we hope to have a clearer picture of the timing and what we’ll build when we build,” added Greenland executive Joshua Cohen.

His phrase “what we’ll build” surely hinted at the plan, not yet public, for supersizing the towers.

Greenland pleads again

Two days after that, Greenland Chairman Zhang sent Gov. Hochul a bilingual letter, recounting that he’d traveled to New York “solely to find a solution with the State Government to the current grim situation.”

He cited the “severe loss building the early infrastructure, with the anticipation that losses can be recovered during the next phase of the project,” but said government delays had since jeopardized progress.

Perhaps anticipating foreclosure, Zhang wrote that, without immediate action, the project would be at risk. Thus, he requested the state to “provide exceptional support”—direct subsidies?—and expedite the approval process, including the tax-break substitute.

It’s unclear whether he got a reply, but no rescue plan ensued. In late November, news of the foreclosure action surfaced.

Financial questions

Before the foreclosure, at the Aug. 2 meeting of the AY CDC, Director Veconi again argued that, as a precondition to public discussion, the advisory board should see a financial analysis of the project’s future, including funds needed to pay liquidated damages.

Despite the board’s request, the parent ESD didn’t deliver such an analysis, perhaps because it never got one from Greenland. Then came the foreclosure.

After that, in a Dec. 29 essay for the New York Daily News, Veconi and Michelle de la Uz, leaders of the BrooklynSpeaks coalition that aims to improve the project, said Hochul should “direct ESD to independently study the economic feasibility of building over the rail yard” and also ask Congress to fund deeply affordable housing.

Revisiting the issue at a Jan. 23, 2024 AY CDC meeting, Veconi observed, “There’s nothing to confirm that this is economical right now, that someone will pay—effectively be able to make the lenders whole—and develop the project as it's been laid out.”

Greenland, we now know, had already concluded that the project, as approved, was not economical, given its plan to expand both the railyard towers and Site 5, though that hadn’t been disclosed.

“The expense of having somebody come through and do an estimation on what would be a speculative real estate project,” ESD attorney Richard Dorado responded dismissively to Veconi, “would be gigantic and would probably be useless.”

Ironically enough, that’s what the ESD in April 2023 had requested of Greenland regarding its proposals: “a detailed analysis of the financial feasibility and sources and uses” of funds.