Does More Open Space Mean Better Open Space? Maybe Not, If Population Outpaces It.

More acreage would come with a larger percentage increase in apartments. Still, a better layout would help.

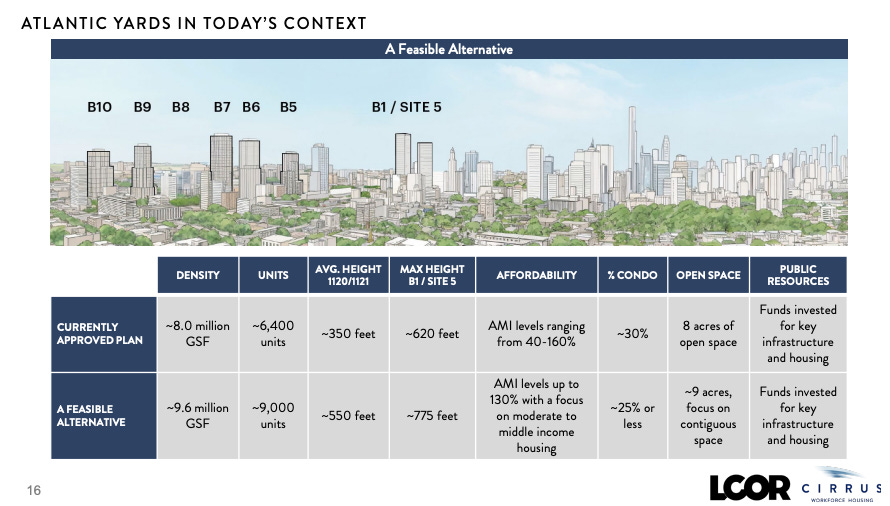

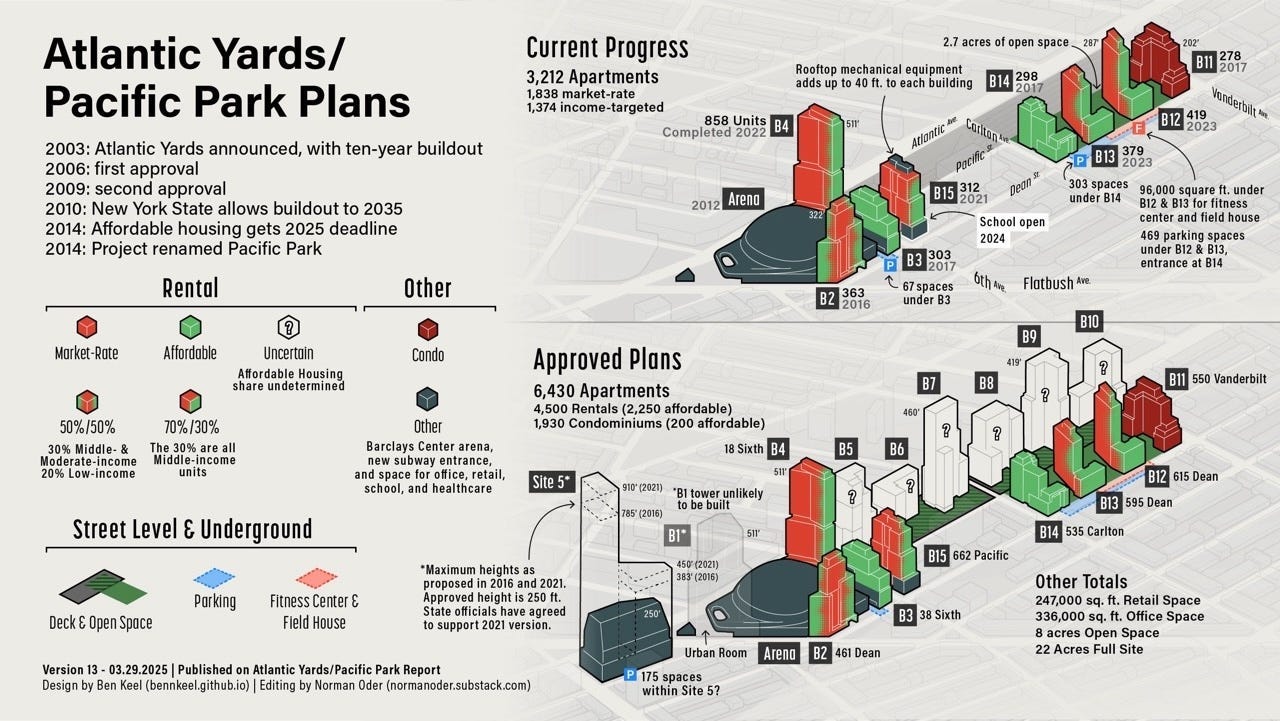

Last week, the new Atlantic Yards development team revealed their “feasible alternative” to complete the project, including a “20% increase” in bulk, which I calculated as far more. (They don’t seem bent on paying for it, either.)

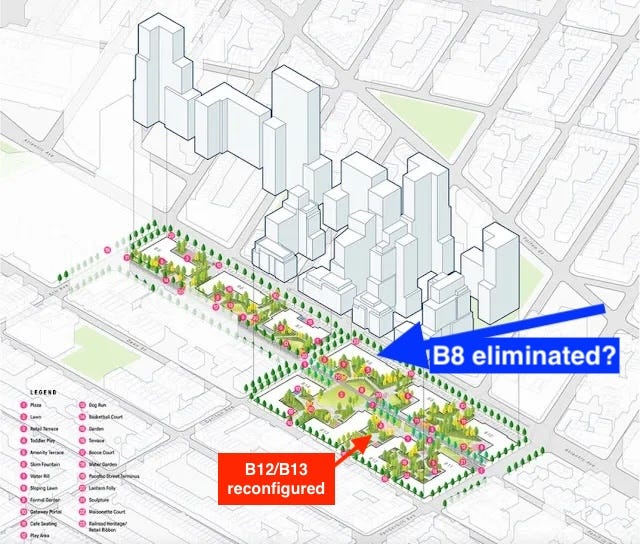

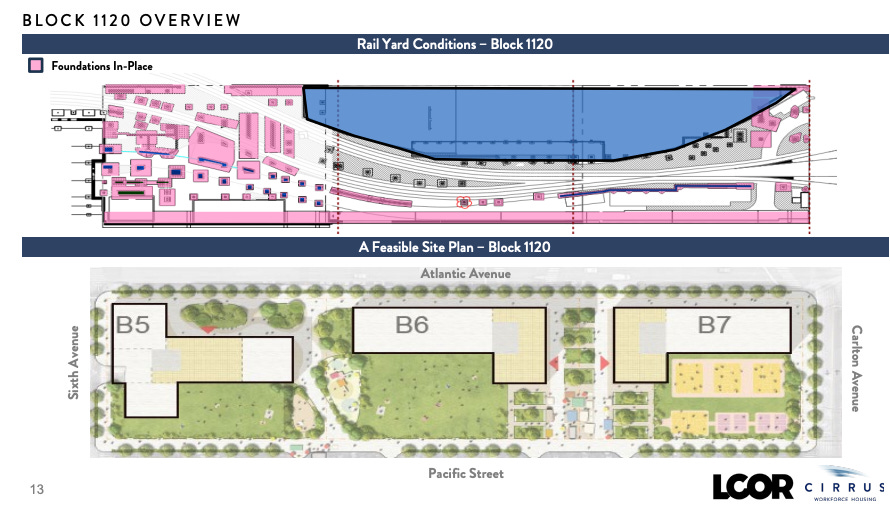

Probably their most welcomed proposal was to eliminate one of six towers slated to be built over the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s (MTA) Vanderbilt Yard, thus adding an acre of open space to the project’s promised 8 acres.

Moreover, the layout over the railyard would shift from a design long criticized for appearing to prioritize space perceived as private courtyards.

Rather, the public space at the parcel previously designated B8—just east of Carlton Avenue and below Atlantic Avenue—would be bordered on two sides by streets, and on the south side by a green passageway in demapped Pacific Street.

It would be a “more contiguous and thoughtful program,” said Joseph McDonnell, Managing Partner of funder Cirrus Workforce Housing, which, with the development firm LCOR, has been designated the permitted developer.

“We want to provide more open space and more thoughtfully programmed open space that becomes a resource to the community,” McDonnell said.

Is more space enough?

While that would create more open space—at least 9 of the project’s 22 total acres—it wouldn’t necessarily offer sufficient open space. First, the ratio of open space per capita would remain well below the city’s goal or even median.

To meet those benchmarks of 2.5 acres or 1.5 acres per 1,000 people, Atlantic Yards would have to include 48 acres or 29 acres of open space—both impossibilities.

Second, the proposed increase in apartments (and new residents) would outpace the increase in open space. That means the “open space ratio”—a standard metric to assess sufficiency—would go down, not up, even if that were mitigated somewhat by better design.

So the name “Pacific Park”—it’s unclear if the new developers would keep it—might remain something of a misnomer.

Solving a problem, too

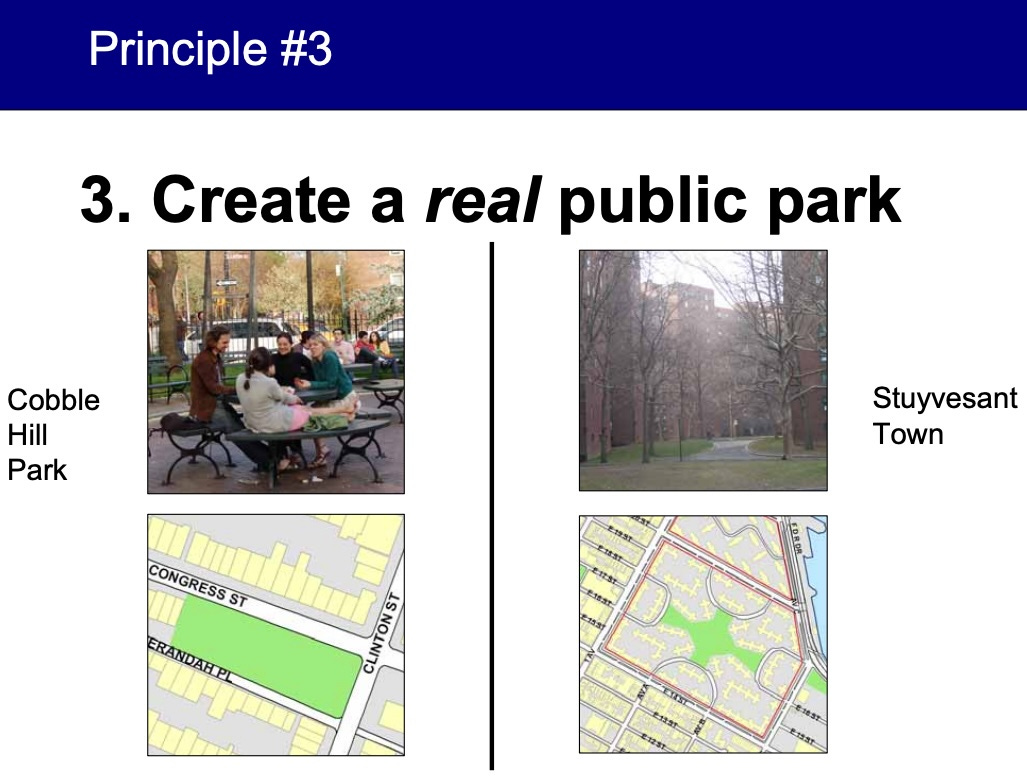

The proposed change at Block 1121 responds to longtime criticism of the open space design, in 2006 from the citywide advocacy group Municipal Art Society (MAS) and later the coalition BrooklynSpeaks, contrasting enclaves between buildings with parks that meet the street.1

The revision also would solve a problem for Cirrus and LCOR.

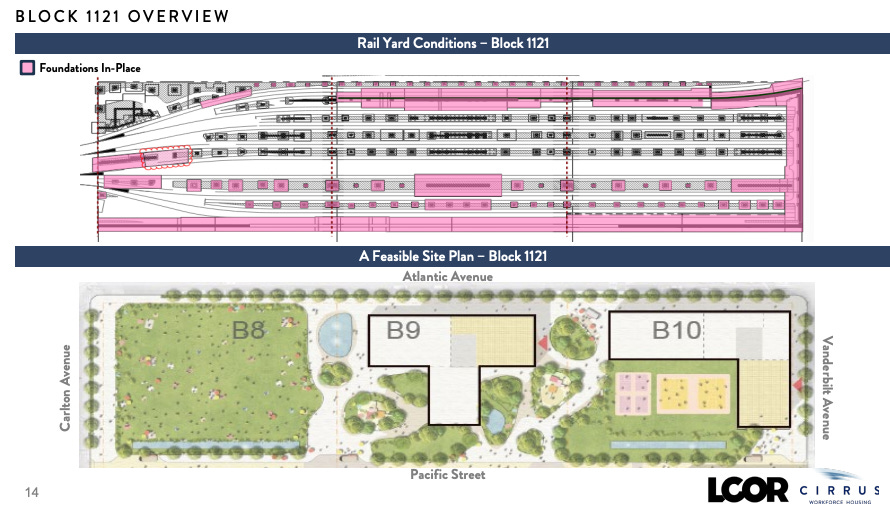

Cirrus’s McDonnell, at last week’s meeting, said original developer Forest City Ratner, which produced the master plan, didn’t understand the challenges facing that B8 parcel. At that time, the eastern block of the then three-block railyard only had one rail track.

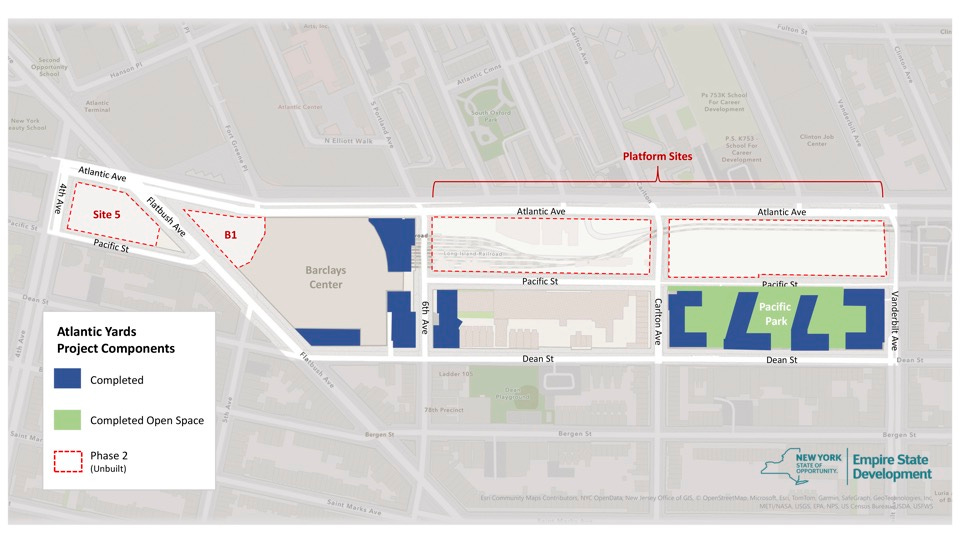

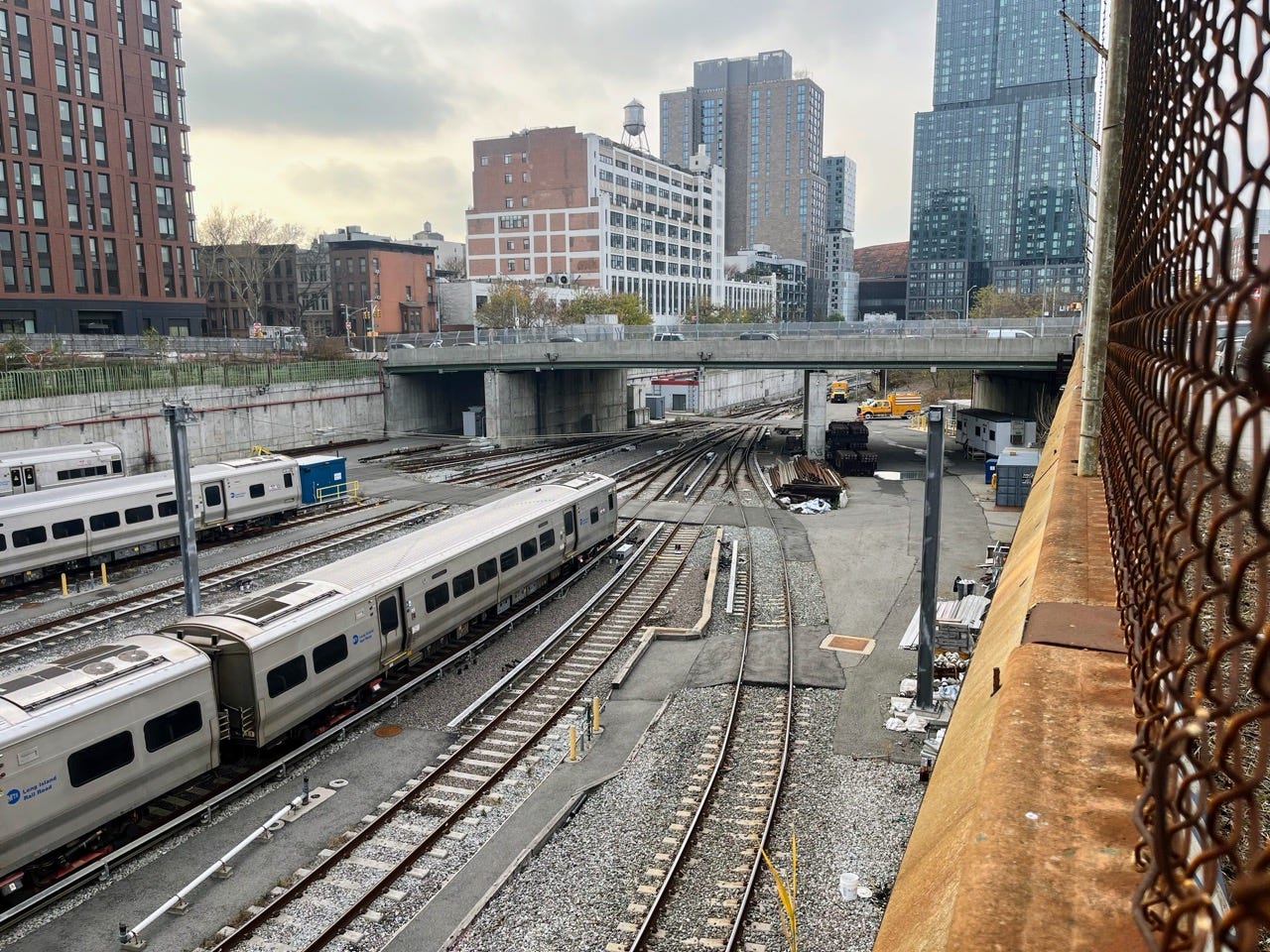

Conveniently, a project outline (above) recently released by Empire State Development (ESD), the state authority that oversees/shepherds the project, shows that single rail track, though today it it has seven tracks. It’s part of a relocated railyard used to store and service Long Island Rail Road trains, which needs a platform to protect it.

Now, McDonnell said, “a large interchange” sits below what was designated the B8 parcel with curving tracks. So it’s “very, very difficult to build there,” he said.

He didn’t elaborate, but a concentration of tracks eliminates space—as explained by the Hudson Yards developers—to support a platform, which presumably needs more buttressing for towers rather than open space.

Indeed, the photos suggest a lesser opportunity to install foundations as the tracks converge. The Block 1121 overview, above, shows fewer foundations at the B8 parcel.

A confounding issue

If McDonnell’s right, though, it’s confounding that state officials at both the MTA and ESD permitted Atlantic Yards to proceed, essentially blessing previous developer Greenland USA’s plan to build on Block 1120, the first railyard block, between Sixth and Carlton avenues.

Does that mean that, had Greenland proceeded to the second railyard block, between Carlton and Vanderbilt avenues, it would have: 1) found a way to build B8? 2) converted that site to open space? 3) walked away from the project, leaving most of the open space unfinished?

Open space goes down

However welcome, the new open space wouldn’t resolve a persistent problem: the amount of “park” has long been inadequate for the project’s residents, at full buildout, much less the surrounding area.

In other words, it wouldn’t be “abundant public green spaces,” as professed.

Cirrus/LCOR, taking a cue from predecessor Greenland, has proposed thinner, taller buildings, making it easier to build (on terra firma) and allowing for a larger amount of more contiguous open space.

As had Greenland, the new joint venture proposes revising the design of the B6 and B7 towers, on the railyard block between Sixth and Carlton avenues, making them thinner.

All told, the elimination of B8, plus the redesigned towers, might result in, say, 9.5 acres of open space. (After all, Forest City was able to increase the original 6 acres of open space to 8 acres.) That 1.5-acre increase would mean an 18.75% boost in total open space.

However, the proposed increase of 2,570 apartments over the approved 6,430 would represent a 40% increase in population. At 2.14 people per apartment, an estimate used in previous project documents, the total population could be 19,260, an increase of 5,500 over the previously estimated 13,760.

Maybe that math’s completely fair, since it’s hard to imagine residents of Site 5, across wide Flatbush Avenue, making the project’s open space a priority.

If, say, we subtracted 900 apartments at Site 5, an additional 1,670 apartments would represent a 26% increase, 3,574 more people, still outpacing the increase in acreage.

The “tricky strategy” behind open space

In Gotham Gazette, Anne Schwartz on Aug. 17, 2006 contrasted Atlantic Yards with Battery Park City, both with open space designed—at least initially, in the case of Atlantic Yards—by landscape architect Laurie Olin.

While both projects (as of then) would have about one-third of their acreage devoted to open space, Battery Park City would have a smaller population, over 92 acres, compared with Atlantic Yards, over 22 acres.

Moreover, the limited open space provided as part of Atlantic Yards relies on demapping streets. As Matthew Schuerman wrote in the New York Observer, part of a Feb. 26, 2007 profile of Olin:

Mr. Ratner, however, needs that street bed in order to increase the open space on the project. Along with streets that will be demapped to make way for the arena, he will gain about 2.7 acres, according to The Observer’s calculations based on the environmental-impact statement.

Architect and commentator Jonathan Cohn called it a “a tricky strategy: rather than decrease the built space, the site can be ‘expanded’ by taking the area of the streets. By demapping the streets and counting them as open space, the project’s ratio of open to built space looks better - as a number.”

Official analysis: it doesn’t matter

Official state documents acknowledge the deficits but say they don’t matter.

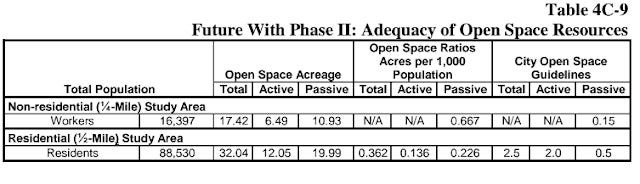

ESD’s June 2014 Final Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (SEIS), Chapter 4c, Operational Open Space, acknowledged that the Department of City Planning seeks 2.5 acres per 1,000 residents, including .5 acres of passive space and 2 acres of active space, while the citywide median ratio is 1.5 acres per 1,000 residents.

“Because these ratios may not be attainable for all areas of the city,” the document states, ”they are considered benchmarks for comparison rather than policy or thresholds for determining impacts.” So the projected .362 acres per 1,000 residents, in the ½-mile residential study area around Atlantic Yards, was not considered a deficit.

Does that projection remain accurate? Unlikely. Since 2014, new buildings have been approved just east of the project, around Atlantic Avenue, adding to the population.

They didn’t add incremental public open space. The new Atlantic Avenue Mixed-Use Plan, east of Atlantic Yards, offers incentives for new open space at a small number of sites, but likely would add further strain on open space resources.

Drilling down

Instead of looking at the ½-mile residential study area, let’s apply the math to the 22-acre site.

If we divide the projected population of 19,260 by 19.26 to get 1,000 people, then we divide the 9.5 acres of open space by 19.26. The result is .493 acres per 1,000 people.

While that ratio is superior to that in the residential study area, it remains less than one-third of the city median, and one-fifth of the goal.

Also, it’s a lower ratio than current projections: with 13,760 people and 8 acres of open space, Atlantic Yards would have .581 acres per 1,000 people.

Never mind

Even if the numbers get worse, ESD likely would again wave it away. According to the guiding CEQR Technical Manual, “a project may result in significant adverse impacts to open space” if the project reduced open space ratios by more than 5 percent in an area currently below the city’s median open space ratio, ESD said in 2014.

However, in areas said to be well-served by open space, like this one--because of the presence of purportedly nearby Prospect Park and Fort Greene Park--”a greater change in the open space ratio may be tolerated.”

That’s debatable. The closest Atlantic Yards building to Fort Greene Park is a 12-minute walk (per Google), while the farthest is 17 minutes, all requiring people to cross wide, busy Atlantic Avenue, which takes more time.

The closest building to Prospect Park is 15 minutes away, and the farthest 20 minutes, though Site 5 would be an even longer walk. So neither park would be a simple stroll.

Something > nothing

The state suggested something would be better than nothing, as building out the project would help make up for the population increase caused by the initial phase of Atlantic Yards.

“While the total, passive, and active open space ratios would be below city guidelines in the Future With Phase II, the overall effect of Phase II of the Project on the availability of open space resources in the study area would be beneficial,” the document concluded.

Today, there’d have to be new calculations. But similar conclusions would be likely.

Would they seek more of Pacific Street?

Would having higher-quality open space improve things? Surely. But even better design has its limitations.

No wonder Greenland, as I reported, after redesigning B6 and B7 to add incremental open space, also asked ESD officials to help them acquire part of adjacent Pacific Street to the south, between Sixth and Carlton avenues, for additional open space.

Pacific Street, between Carlton and Vanderbilt avenues to the east bordering the B8-B10 sites, has already been demapped. After serving as construction staging, it would supply key open space once Block 1121 was transformed with a platform.

Though that proposal was not fleshed out, it implied adding public property without compensation. It also implied that shrinking the building footprints wouldn’t be enough.

That challenge will persist. So, while transforming the B8 parcel into open space might make sense, the big picture deserves assessment. As always, the devil’s in the details.

BrooklynSpeaks was formed by MAS, but the latter ultimately left it.

Thanks Norman, good work. I would just add that in addition to the discussions about the amount of green space within the site boundaries and what to do with it, to consider a new project plan the (new) development team should update the original commitments made about addressing the public realm on the streets the project faces, especially the mess in front of Site 5. No one wants to walk to Fort Greene Park, not so much because of the distance but rather the danger and sheer unpleasantness of crossing arguably the most degraded, pedestrian (and bike) unfriendly traffic mess in the city.

From the start the "park" has never been a real Park with all the rights of NYC's parks under our local laws. This has always been an amenity for AY's quasi gated community & one that IIRC is subject to management decisions such as closing times, etc. From this perspective the numbers we are supposed to accept in exchange for all the added density are just improving an amenity that will be used to attract tenants and not benefit the general public in any meaningful way.