Can Public-Private Development Projects Be Fixed? Well, Maybe.

But it requires better monitoring, new procedures (approve in phases?), and better execution. Plus, legislators and the public must step up. The press, too.

So, can public-private development projects be fixed?

Well, maybe, said some experts in a Dec. 15 panel (video below) sponsored by the BrooklynSpeaks coalition, the City Club of New York, and Voices of the Waterfront, aiming to look at the ongoing Atlantic Yards project and the advancing Brooklyn Marine Terminal (BMT) project.

But it’s a tall order that requires new approval procedures, better monitoring, and more competent execution, all backstopped by engaged legislators and an engaged public to oversee opaque government entities like Empire State Development (ESD), the state authority that oversees/shepherds Atlantic Yards. (Plus, I’d argue, the press.)

While the panel did not get to the proposals in my preview article—third-party experts to assess financial feasibility and environmental impact, plus making the Barclays Center operator pay for a permanent plaza—the latter received indirect support, in my eyes.

For example, one panelist suggested that each phase of a megaproject be approved separately, allowing for government counterparties to adjust the terms. Another proposed that tax exemptions have a sunset clause keyed to the success of the project.

In other words, if the arena operator, thanks to direct and indirect government help, has made a huge profit, the public should get a piece of it. In the case of Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park, such funds could be used to cross-subsidize the remaining project, for example fostering more deeply affordable housing.

It’s worth noting that, despite the tempting “broken promises” frame that many (including this writer) use, one panelist argued for increased government competency. That’s a fair point, but, as Atlantic Yards shows, the issue’s also political: government agencies have parroted unrealistic promises rather than pushed back.

Setting the frame

Moderator Laura Wolf-Powers, an urban policy professor at Hunter College, described megaprojects: they not only reshape the built environment and have broad economic impacts, they “have very long investment time horizons, ten to 30 years, require significant public and private capital, and political risk taking and resources.”

Often, they’re sponsored by public authorities or development corporations, which implement such projects, which offer the advantage, at least to proponents, of being outside the political process. On the flip side, they’re less accountable to the public and elected officials, leaving them with little recourse when promises fall short.

A state solution?

Wolf-Powers noted that one panelist, State Sen. April Baskin (D-Buffalo), was unable to attend. Frustrated by unfulfilled commitments regarding a Community Benefits Agreement for the new (and government subsidized) Buffalo Bills stadium, Baskin has sponsored legislation to establish a post-construction compliance review board, with penalties for noncompliance.

It also would establish utilization goals for MWBEs (minority- and women-owned business enterprises), impose a local hiring requirement, require living wage, and create a Community Grant Program, matching “at least 5% of the state’s construction investment to fund socioeconomic projects in the municipality.”

Costs and benefits?

What benefits are expected from these projects, Wolf-Power asked Moses Gates, VP for housing and neighborhood planning at the Regional Plan Association (RPA).

“Everything should be on the table in a negotiation,” Gates observed, suggesting that the planning and design elements may be the easiest to negotiate and expect. He cited the “vey extensive citywide engagement process,” which the RPA furthered, to ensure elements in the World Trade Center redevelopment.

“The financial part is tougher,” he observed. Indeed, it is, as was elaborated.

Holding ESD accountable

Elizabeth Marcello, who also teaches at Hunter and wrote the 2023 Open ESD report for the watchdog group Reinvent Albany, suggested that a new mechanism for ESD oversight might not be necessary.

Rather, she said, ESD, the gubernatorially controlled economic development authority, should be be required to follow the law. The authority announces board meetings so close to the public meeting date that “the public doesn’t even have time to review and respond accordingly.” (I’ve written about that.)

“These are very basic things that I think the legislature could hold ESD accountable for even now without the creation of any new entity, and I don’t see them doing these things,” Marcello said.

She recommended that existing watchdogs, such as the state Comptroller’s office, conduct more audits of ESD programs and projects.

Also, the Authorities Budget Office, or ABO, is “so underfunded and understaffed, it’s practically a joke of an office,” but a fully funded ABO could oversee ESD. Then again, she noted, its leader is appointed by the governor, and “public authorities largely do the bidding of the governor.”

Auditing Atlantic Yards?

“What if we did a forensic audit of… Atlantic Yards,” Marcello mused. While she cited organizations like BrooklynSpeaks and journalistic watchdogs like me, “I want the state legislature right to stand up and demand answers on behalf of the public.”

That would be… interesting, especially if it went beyond the fiscal impact to the city and state to address the benefit to the parties involved. It surely would show that the arena operator is doing very well and maybe doesn’t need future tax breaks/tax-exempt financing and/or could be asked to pay for a permanent plaza.

Little balance

Marcello also cited ESD approval of an opaque Penn Station redevelopment plan. “They get away with this because I think the average New Yorker has no idea what’s going on,” she observed. “The fact that public authorities act in total darkness and outside of public view and comprehension, yet have so much power, it’s just shocking.”

Well, that’s partly because the powers of civic groups are limited, legislators are underpowered, and the press has winnowed. Remember when the late Assemblymember Richard Brodsky—bombastic and self-serving but also impressively informed—could grill state officials at public hearings?

Roadblocks

Pratt Institute planning professor John Shapiro, co-author of a recent article in Common Edge, No More Atlantic Yards! (though it was mostly about ensuring public value from public-private partnerships), observed that environmental impact statements and fiscal impact analyses come too late. A social impact analysis is needed from the start.

Why hasn’t it be done? Well, New York City has no comprehensive plan to set out public needs or objectives, which leaves the Mayor in charge, though the time frame for large projects exceeds even two terms.

In New York City, such projects are typically sponsored by the New York City Economic Development Corporation, a mayoral entity insulated from oversight. A co-sponsor, like the City Planning Commission, should be involved, he said.

Then comes implementation strategy. “Battery Park City illustrates how to do it right,” Shapiro said, noting that, after a plan was devised, “they sold the parcels one by one, with strict expectations about what would be achieved with the revenue or the design of each of the buildings.”

“Atlantic Yards illustrates how to do it wrong,” he said. With a sole developer involved, as with Atlantic Yards, “the city is a prisoner of that one developer’s capacity, marketing ideas, financing ambitions, leadership, ability to be flexible as markets and interest rates and other things change, and also a prisoner of the ability of that developer to just walk away.”

That dynamic has led the city to supply $2 billion in taxpayer assistance to pay for the platform and complete the second half of Hudson Yards. “It’s not a sunk cost for the developer any more, as it would be if it was a private development,” he said.

Timing, and phases

A new mayor may not retain the priorities of the previous one, Shapiro observed, and “the opposition stakeholders, press, and public attention have shifted to the topic of the day. So it’s very hard for the likes of [organizer] Gib Veconi and his organization [BrooklynSpeaks] to keep reminding the world that there’s broken promises” regarding Atlantic Yards.

What could be done? “Each phase should be subject to its own approval process,” Shapiro suggested, allowing for reassessment. With Atlantic Yards, the expected revision of the plan will require re-approval, but the process is foreordained, with the governor in charge.

An alternate reality of meaningful re-approval implies, for example, that the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s (MTA) decision in 2005 (revised in 2009) to sell development rights to the Vanderbilt Yard addresses only the development rights then on the table.

That would mean that the new joint venture’s request for 1.6 million more square feet of bulk was not part of the deal and, contra their seeming expectations, would require payment.

The role of the public

Shapiro also suggested that the city or state guarantee the public benefits, not the developer. (That could be expensive.)

“Frankly, our development community is simply spoiled,” he said. “Megaprojects have mega expectations, mega impacts, mega politics. They should be controversial. If they’re not controversial, we’re not thinking hard enough.”

“Not that they should be thwarted,” he said. “But I’ve yet to find a community process or review process that has not improved projects, so long as the discussion is realistic, up to date, and there’s trust. Which broken promises… does not create.”

What’s the right frame?

Raju Mann, president and CEO of the Battery Park City Authority (BPCA), and the former City Council Director of Land Use, suggested the issue might not be holding agencies accountable to promises, but rather: how do we make sure these projects happen the way they’re intended.

He noted that academic Bent Flyjberg (my previous coverage) had analyzed numerous megaprojects—public projects, not public-private partnerships—and found significant cost overruns. (Also: delays.) One reason, said Mann, is “optimism bias… around the schedules and costs.”

To deliver such projects, Mann suggested increasing capacity of city agencies, ensuring a very engaged public, and requiring “elected officials to resist the temptation to announce something before it’s fully thought through.”

(That, of course, was not the history of Atlantic Yards, given the triumphant enthusiasm of elected officials in December 2003 for a new arena and major league team.)

Lessons from BPC?

Contra Shapiro, the BPCA’s Mann observed that Battery Park City has a more fraught history, with a 14-year gap between the authority’s creation and the opening of a building. Original promises of affordable housing could not be met, given that New York was recovering from disinvestment in the 1970s.

“And I don’t think that was because there was a failure to hold people accountable,” Mann said. “I think it was a changing economy in the ‘70s that nobody could project.”

Since megaprojects face unpredictable market cycles, political cycles, and economic cycles, he suggested “some humility” about not just venturing into them but also criticizing them. (I don’t disagree, but that humility also should apply to scenarios promoted by developers and their allies in government, which are typically rosy.)

So Battery Park City, as of 1981, might have been seen as a failure, Mann observed, with significant expenditures on parks and streets, but with no housing yet. So projects at this scale must be “measured in decades, if not longer.” (Fair enough. With Atlantic Yards, though, the buildout was always claimed to be ten years.)

Agencies vs. developers

How, asked Wolf-Powers, “to assess how much return the developers are making and what is considered appropriate return on investment for public amenities, like housing, park, schools, etc.?”

“I never begrudge developers their profits,” said Shapiro. “They’re the ones taking the risks. They’re the ones raising the capital, but it’s not part of their mission statement or job to make sure the public benefits are realized. Their primary interest will always be in the public benefits that serve their marketing purposes the most.” So a waterfront park is more valuable than ground floor industrial use.

The agency in charge of the project, Shapiro said, must be “as smart as the developer.” He noted that a colleague observed that “that’s impossible, because agencies have multiple purposes and developers have single purpose and pay better.” Maybe, said Shapiro, but they just have to “be smart enough.”

Also, I’d say, not so influenced by the governor that they hire outside experts to ratify unrealistic ideas, like the ten-year buildout.

Shapiro acknowledged the lapses with Battery Park City but said the key was the state authority keeping control. Given that the market changes, he observed, “Phase One should be the only one that’s approved,” requiring promises revisited in light of market changes.

Some broken promises good?

Mann asked, “Is there a world where the evolution of projects to reflect changes makes sense, as opposed to the broken promises framing?” He noted that he’s happy that the early Battery Park City promises—of huge, large-scale urban renewal buildings”—were broken.

Similarly, it could be argued that the early promises of Atlantic Yards—a tower looming above the arena with an enclosed Urban Room to serve as an entrance to not just the arena but also the transit complex and the office tower above—was unrealistic.

The plaza is crucial to arena operation and advertising/promotion. Still, the arena operator should be required to pay for it, and enclosed open space—as BrooklynSpeaks has suggested—should be provided elsewhere in the project.

Similarly, architect Frank Gehry’s designs for buildings that enclosed publicly accessible open space into seeming private courtyards, was revised by him to at least create corridors, then later by subsequent development teams to supply more public-seeming open space and to take advantage of building designs that rely on terra firma.

It’s a little tougher to justify, however, broken promises of Atlantic Yards affordable housing.

The role of government

Marcello pointed back to the role of government, citing a study that Reinvent Albany did with The New School regarding Penn Station, revealing—as ESD had not—that even under the best-case scenario, the developer would get $1.2 billion in tax breaks.

Gates observed that the easiest subsidy for the city is a tax exemption, because it doesn’t have a lot of strings, and the costs are delayed.

He supports “an assessed value cap on the exemption,” which means if the project is successful and “worth twice as much money as we had underwritten for--you don’t get the exemption on that extra value. You then start to pay taxes on that extra value that was unanticipated and wasn’t part of the thinking behind the original construction of the plan.”

While Gates—a former official at the Association of Neighborhood and Housing Development, which represents affordable housing and neighborhood nonprofits—was talking more about residential construction, that logic could be applied to the arena, to my mind.

“This is something developers don’t like, because developers feel they’re taking the risk, and if they hit the home run, they should get all the upside,” he said.

(Remember, the risk for Joe Tsai, whose company BSE Global owns the arena company and the Brooklyn Nets, was hedged by what he calls the NBA’s “kind of a socialist setup.”)

“But if you’re in a public-private partnership,” Gates said, “the public is a big part of that, and the public also deserves some of the upside if you hit a home run.”

As I’ve recounted, during developer Forest City’s 2009 renegotiations with the MTA over Vanderbilt Yard payments, the RPA proposed new terms, including “an opportunity to realize much greater long-term revenue, possibly by negotiating a share of future revenues from the project that could exceed annual payments for development rights.”

The need for competition

Prodded by moderator Wolf-Powers as to why such projects often have a single counter-party, Gates said, “the more competitive the process, the better it is for the public.” However, a market that’s new, or complicated doesn’t attract a lot of bids.

With Atlantic Yards, developer Ratner had the inside track on the MTA’s railyard. Only after public pressure did the MTA put it out for bid. Even though rival Extell offered more cash ($150 million vs. $50 million), the MTA decided to negotiate only with Ratner.

Yes, Forest City arguably had a more complete bid, with more promises of public benefit—even as the MTA lowballed the cost of infrastructure—but the MTA didn’t even try to pit two bidders against each other. That’s because key elected officials wanted an arena.

Then, in 2009, the MTA agreed to revise the terms, with the developer pledging only $20 million for the portion needed for the arena (and, it turned out, the giant B4 tower), with the remaining payments spread out until 2031, at an implied 6.5% interest rate, which one real estate analyst called “a real coup.”

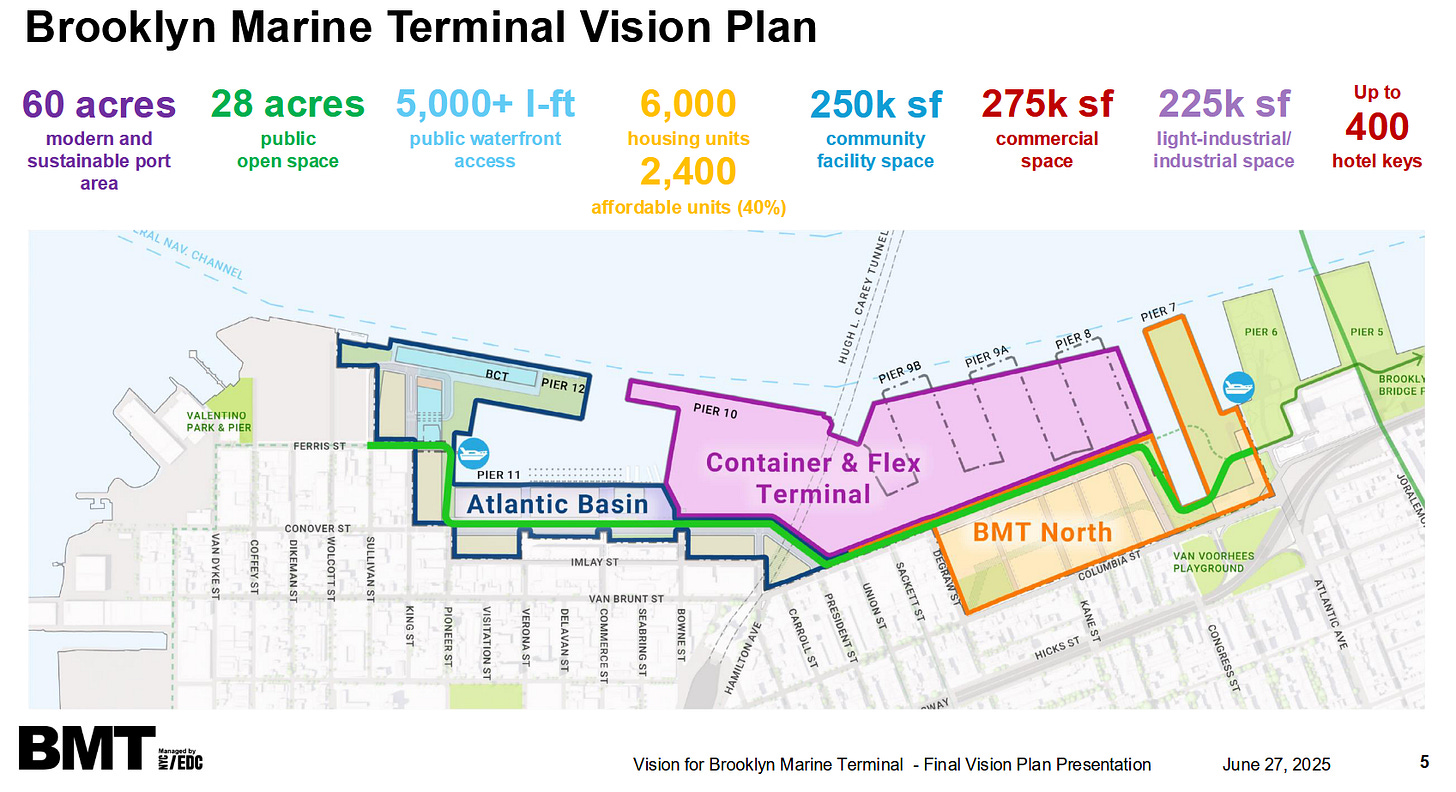

What about the BMT?

Wolf-Powers asked about what the board of the new Brooklyn Marine Terminal Development Corporation could do. Could Shapiro’s idea of phasing be applied?

Yes, he replied, but that would require city control, not state control, “and everything that’s going wrong in Atlantic Yards can go wrong again here.”

“As with Atlantic Yards, I think there’s promises being made with no path to implement them in the project,” he said. “Atlantic Yards promising the affordable housing on the most expensive land to create the overbuild was perhaps sincere, like ‘we hope we’ll be able to pull it off.’… But that development team is now long gone, and the numbers never worked to begin with, so they still don’t work.”

I think that’s a little generous, given other evidence of insincerity.

With the BMT, Shapiro said, “essentially every major stakeholder was promised something,” and those costs may not be met. There might be a clash between maritime and residential use, and that both would be affected by climate change.

Shapiro suggested the BMT plan required more than $1 billion worth of infrastructure. “I think it’s overwhelmingly for the housing and not for the maritime, even though it’s described as being for the maritime or just being lumped together,” he said. “The lack of transparency communicates a weakness of argument.”

He questioned using the revenue from housing to pay for the rehabilitation of the maritime section, which has value in itself serving “blue highways,” and said promises of funding to fix nearby public housing should not be linked to a risky project. That, he said, is “an abrogation of the responsibility” of government.

Marcello recommended that those working on the BMT project have high expectations: “Hold state entities accountable. Hold government elected officials accountable. Hold developers accountable.”

One commenter, noted the moderator, pointed out that the BMT plan, with multiple developers, might resemble Battery Park City more than Atlantic Yards.

“Delivering projects of this scale and complexity over decades is really hard,” Mann said. Acknowledging he might sound technocratic, he said it was important that the BMT plan could have staff able to answer Shapiro’s questions credibly.

The big picture

What about deciding on such projects in the first place, asked Wolf-Powers?

“That’s a deep question about what does democracy look like and how do we make decisions,” Mann observed. “We’ve got certain processes in place today. That’s how we’ve chosen to structure them.”

“If we think a new construct is going to change outcomes, I’m less convinced of that,” he said. “Frankly, I think it’s really informed people, really engaged elected officials, really healthy debate. I think that is more likely to change outcomes.”

Shapiro said the Department of City Planning was understaffed and needs to be bolstered.

“So I want to take a punch, if you will,” Shapiro said. “The opinion I keep hearing among people who behind the scenes are influencers within government, is that communities are definitionally NIMBY. They should not be listened to, that the only people who show up are the homeowners, and that the renters are there for--their interests are being discounted.”

So it’s a “whatever it takes moment” to get something built, which the development community welcomes. “So it’s okay to overpromise and under-deliver,” he said, channeling government thought, “because otherwise we’re just playing into NIMBY hands.”

That argues for more accountability. While the “world’s eyes were on World Trade Center, “ Shapiro observed, that won’t happen for other projects.

Gates suggested that interest in urban planning had grown significantly the last two decades. “You have all you have lots of publications that are dedicated to New York City,” he said. (I’m not sure that, for example, the new New York Review of Architecture makes up for a disengaged New York Times.)

“You have lots of nonprofits,” Gates said, citing the popularity of Open House New York, which operates popular weekend events every October. (Sure, there’s interest, but not deep knowledge, as I’ve learned leading tours on those weekends.)

What about Atlantic Yards?

Summing up, Veconi said he “really appreciated [Mann’s] call to engage the public fully. I also believe this is a very critical part of accomplishing anything in New York City, relative to planning.”

“I believe the call to favor competition and avoid single-source projects is very, very important,” he observed, noting the BMT plan may offer more opportunity than Atlantic Yards.

“The idea that you have the right people overseeing the project at the government level,” Veconi said, “is an important success criteria that unfortunately, we haven’t really had at Atlantic Yards, and it’s single source structure.”

“And the call to approve in phases, rather than to have a long, multi-year [ESD] approval that can be evergreen and continue to be changed over time, is very good advice,” he said.

Also, Veconi noted, “we have to make sure the project is feasible” for promises to work. “That is something we’ve also learned at Atlantic Yards and hopefully it’s a lesson that other projects like BMT can learn from.”

The phase-by-phase approval idea is probably the most actionable takeaway here. When Atlantic Yards got approved as a monolith with a ten-year timeline that everyone knew was unrealistic, it locked in bad incentives from day one. I consulted on a smaller mixed-use project in 2018 where the city insisted on staggered approvals tied to deliverables, and while it frustrated the developer initially, it kept everyone honest about what was actualy feasible.