The Big Atlantic Yards Winners? Billionaire Team Owners Prokhorov and Tsai

The Brooklyn Nets' boom in value relies on the government-aided Barclays Center. Why can't the public get some of the upside?

One great irony about Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park is that the real-estate project, excepting the arena, has been a financial failure for original developer Forest City Ratner and its successor Greenland USA.

That also means a failure of prognostication and oversight by all the public officials and agencies that have approved and shepherded the project. (Yes, advocacy groups and journalists got it wrong, too.)

Thus the highly touted public benefits of Atlantic Yards—affordable housing, open space, jobs (both construction and office), removal of blight, new tax revenues—have been delayed and diminished, though such projections were used to justify public support.

It’s unclear how and whether the project, including some 3,200 apartments and five acres of open space, will be completed. The six sites for towers over the two-block, below-grade railyard rely on an expensive platform. Rights to build those sites are the subject of a twice-delayed foreclosure auction, rescheduled for April 30—but who knows.

The big winner

Meanwhile, the National Basketball Association’s Brooklyn Nets have been a financial supernova. Some may see them as Brooklyn’s “hometown team,” as propagandized by ownership. But they’re an astoundingly—if somewhat belatedly— successful sports entertainment corporation.

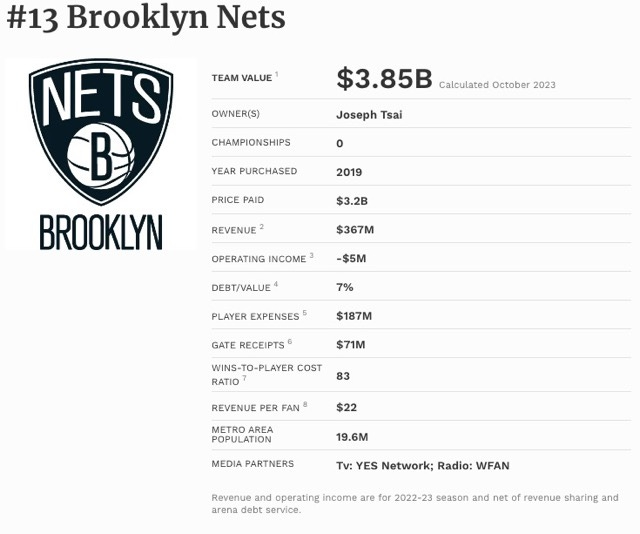

Consider: in January 2004, developer Bruce Ratner, with other investors, agreed to pay $300 million for the New Jersey Nets, well more than Forbes' $218 million valuation, reflecting the upside in the planned move to Brooklyn. ( That presumably included the short-term arena lease at the Meadowlands.)

Russian oligarch Mikhail Prokhorov, in a series of transactions as well as ownership investments starting in 2019, spent—according to his deputy—less than $1.5 billion on the team and arena company.

Prokhorov from 2017 to 2019 sold the properties to Alibaba co-founder Joe Tsai for about $3 billion, a huge profit. (Some say $3.3 billion, but I think that’s overstated.)

Late last year, Sportico valued the team and arena company at $3.98 billion. Forbes estimated $3.85 billion.

Now Tsai may cash out. He may sell a 10% to 15% slice of those holdings at a reported valuation of $4.8 billion, 16 times Ratner’s original cost.

Sure, the arena’s net operating income has consistently trailed profit projections and in several years hasn’t even covered construction debt, forcing billionaire Tsai to backstop the finances.

But if he raises $480 million to $720 million from the immensely rich Koch family, reported as potential minority investors, he’ll profit handsomely.

So, big picture, the arena company’s a huge success, since it’s paired with the team and crucial to the rise in paired value. The Brooklyn arena positioned the franchise in a way a New Jersey arena never could have.

Why the rise?

The increased value of NBA teams depends on a rising tide, as teams share revenue, see TV contracts increase, and have access to new sponsors, gambling, and international audiences.

New rules that allow sovereign wealth funds and other investment vehicles to buy minority shares in teams have goosed valuations.

Missed opportunity

Today, it’s clear that the rise in the Nets’ value was a missed opportunity for the public to gain some fraction of the upside, funds that could have been used for, say, affordable housing.

Wait, isn’t this just private commerce? Did the private parties take all the risk? Nope.

Government assistance and forbearance, direct and indirect, for the new Barclays Center arena enabled a pro team to move to Brooklyn, part of the nation’s media capital.

Public land, private venue

Most of the arena construction is said to be privately funded, though that deserves a huge asterisk. The nominal public ownership, as I’ve written, allows for tax-exempt bonds, and significantly lower financing costs. That means the team owner owns the arena operating company, Brooklyn Events Center.

Tax exemption for the arena site means that, rather than pay taxes on the assessed value, which has increased to an astonishing $110.2 million, those payments go to pay off construction debt.

Watchdog legislator Richard Brodsky likened it to sending “my tax payments to the bank to pay off the mortgage.”

The counter is that, well, the land was mostly tax-exempt, already. Well, then, should the developer have paid just $20 million to the MTA for development rights over the portion of the tax-exempt railyard used for (part of) the arena? Seems like a bargain.

Yes, other sports venues are on tax-exempt land, such as Yankee Stadium and CitiField, and Madison Square Garden has its own tax break. None are justifiable today, even if they once (arguably) were.

Arena benefits

The city and state each offered $100 million in direct cash, with the city’s $100 million used to reimburse Ratner for seemingly generous payments to landowners in the wake of the arena. Then the city added $105 million.

The state allowed Ratner to renegotiate the bid for development rights over the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s 3-block, 8.5-acre railyard, ignoring a rival that bid more cash, because, well, it offered no arena.

(Forest City promised $100 million, doubling its $50 million bid, but Extell had bid $150 million. Forest City said its overall bid was worth more. If so, there was never a true bidding process to clarify that.)

The state pursued eminent domain to dislodge property owners and leaseholders. The city offered public property, including a building and streets, for free.

When in 2009 Ratner pursued renegotiations of project terms, allowing a delayed process for eminent domain and a faster delivery of public cash, city and state officials acquiesced without asking for reciprocity.

The MTA allowed Forest City to pay $20 million for the railyard piece needed for the arena, with the rest of the debt paid off at a gentle 6.5% interest rate, over 20 years. The state agreed to a smaller replacement railyard, used to store and service LIRR trains: seven tracks, not nine, as originally proposed.

The state allowed the sale of arena naming rights, never considered—or calculated as—a subsidy. Barclays originally promised $300 million over 20 years, but that was revised to $200 million after the departure of original architect Frank Gehry.

The state encouraged the developer’s use of immigrant investor funds under the EB-5 program, even sending a state official to China to tout the project to unsophisticated investors.

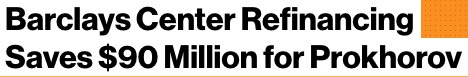

By the time Prokhorov in 2016 went back to refinance the arena bonds, taking advantage of lower interest rates and saving an estimated $90 million for the arena operator over time, again no reciprocity was requested.

Missed opportunity: the MOU

Though few remember, the possibility of greater public benefit was baked into an 2005 agreement, though public agencies have ignored it.

In 2015, the New York Islanders moved to Brooklyn, with a purportedly "ironclad" 25-year lease. That could’ve triggered a payment.

Remember: if a second professional team arrived at Barclays, according to the February 2005 Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) signed by the city, state, and developer Forest City, "additional rent and other terms" would be negotiated.

But that document was nonbinding, and no such clause was in the later guiding Development Agreement that Forest City signed with Empire State Development Corporation (now known as Empire State Development), the state authority that oversees/shepherds the project.

Neither state officials nor elected officials brought it up.

Nor was the issue raised when Tsai bought the WNBA’s New York Liberty in 2019 and a year later moved them to Brooklyn. Last year, when an improved squad made the league finals, they seemed to be building an audience, averaging 7,777 fans, a big leap from the previous year’s 5,327.

Sure, the Liberty’s shorter season, lower ticket prices, and generally lower revenue do not double the Nets’ fiscal presence. But the arena is an ever more valuable canvas for advertising and marketing, even as promises of low-cost Nets tickets lasted just one year.

Again, if the arena operator benefits, shouldn’t the public get a slice?

Missed opportunity: the RPA’s advice

During Forest City’s 2009 renegotiations with the MTA, the business-backed Regional Plan Association (RPA) proposed pragmatism. "While there has been little time to digest the proposal," the RPA's Neysa Pranger observed that Atlantic Yards now offered "greatly diminished" public benefits and likely would be "redesigned and renegotiated."

Believing the market wouldn't recover soon, the RPA proposed new terms, including:

The MTA should either receive a larger upfront settlement or an opportunity to realize much greater long-term revenue, possibly by negotiating a share of future revenues from the project that could exceed annual payments for development rights.

That doesn’t precisely translate to getting a share of the Nets’ future value but instead future revenues. But the concept is clear: share the wealth.

The cost of decoupling

The team and arena were decoupled from the rest of the project when Ratner needed a new investor, Prokhorov. However driven by practicality, that came with significant consequences.

Notably, it’s harder to argue that arena profits should subsidize other parts of the project, since those profits don’t go to the real-estate developers.

However, the issue’s more complicated.

Smooth operation of the arena, it turns out, relies significantly on the plaza—now on its fourth sponsor, Ticketmaster—as a safety valve for crowds. So that plaza bolsters the value of Tsai’s holdings.

Remember the 2022 kerfuffle about the unbuilt Urban Room, the glass atrium that would’ve replaced the plaza, at least if the flagship tower, which Gehry dubbed “Miss Brooklyn,” had been built?

New York State seemed very unwilling to enforce the $10 million in fines, arguing that the plaza supplied significant public value. Yes, but that value goes more to the private arena operator.

So if that failure to build the Urban Room benefits the arena operator, why shouldn’t it be responsible for some of the fines?

More importantly, the arena operator benefits enormously from the failure to build “Miss Brooklyn,” since construction would interfere significantly with arena operations.

So the decision not to build it, leaving the arena as a marquee and icon, benefits the arena operator.

What about Site 5?

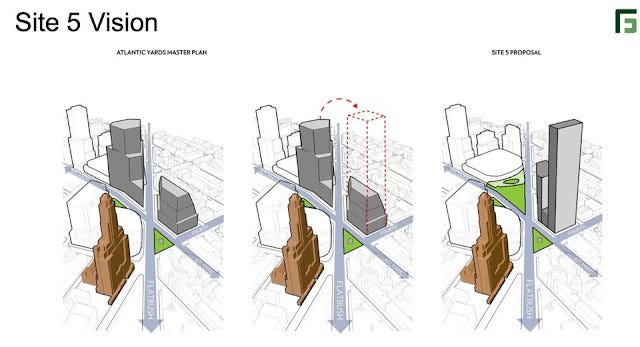

No real estate developer discards buildable square footage. In 2015, Greenland Forest City Partners—today without Forest City—began floating a plan to move most of the bulk of the unbuilt B1 across Flatbush Avenue to Site 5, long home to the big-box stores P.C. Richard and the now-closed Modell’s.

A substantial 250-foot, 440,000 square foot tower had already been approved there.

The new plan would enable a giant two-tower project, then estimated at rising 785 feet, with more than 1.1 million square feet. It also would imply the rest of B1’s bulk could be moved to other parcels, over the railyard.

That’s the last remaining Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park site outside of the foreclosure sale.

Today, the plans might be even more ambitious, given the larger towers approved nearby in Downtown Brooklyn.

Larger towers at Site 5 and over the railyard mean more apartments and more revenue—and, potentially, more untoward neighborhood impacts.

(Don’t be surprised if go-to consultant AKRF produces a study that concludes that such impacts would be minor, easing approval of a major change to the project plan.)

That additional revenue benefits Greenland, or its successor. And the failure to build the already-approved B1, benefits Tsai, who surely doesn’t want construction obstructing arena activities or blocking that valuable signage.

So why shouldn’t the arena operator be required to offer public benefit in exchange for keeping the plaza and avoiding a giant tower.

Public share?

When the Tsai deal was finally completed in 2019, Slate’s Ben Mathis-Lilley estimated that the public deserved some piece of Prokhorov’s $2 billion profit. (It may have been more like $1.5 billion, but still a lot.) He wrote:

In other words, New York’s elected officials decided Brooklyn was a good place for a basketball team, then spent an enormous amount of taxpayer money to recruit a team to play there and to prepare a space for that team to play in. They then let a guy from Russia walk away with the $2 billion in profit that this created—profit that was basically guaranteed given that previous sales have established that it is all but impossible to lose money buying an NBA team no matter how badly you run it. (And Prokhorov did for the most part run it quite badly, with a recent uptick that took place only after he fired his initial management team, which had driven the franchise into the ground.)

What if, instead of doing this, New York had just bought a stake in the Nets itself, then sold the team after 10 years like Prokhorov did? I’ll tell you what would have happened: It would have $2 billion more than it does now, enough to, for example, cover several years’ worth of the budget shortfall that’s helping cripple New York City’s delay-ridden subway system.

Well, New York would never have owned the team outright—again, not a core competency. But it should’ve negotiated for some share of the upside.

Other benefits: the advertising canvas

In his Nov. 1, 2012 review of the arena, New York Times critic Michael Kimmelman, generally praised the arena but also observed:

That the center, like every other sports arena, serves both inside and out as a giant billboard for corporate naming opportunities (my favorite: the Calvin Klein V.I.P. Entrance) deserves mention because naming rights and other financial gains from the arena should be factored into the subsidized housing equation that remains one of the major obligations made by the developer, Bruce C. Ratner.

City housing subsidies are limited.… That Barclays sign should help pay for something besides its own bad taste.

That “giant billboard for corporate naming opportunities” has since been augmented significantly. The exterior of the subway entrance. The horizontal back wall visible as you enter the subway. The notable LED “wall” over the arena doors.

Even the conceptual art, “Belong Brooklyn,” arguably serves as arena advertising as it beckons, “You belong here.”

Is it too late?

Well, is all this hindsight too late?

One lesson from Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park is that everything is negotiable. Project terms and contracts have been renegotiated multiple times, or contract clauses ignored, always redounding to the benefit of the developers and owners.

Remember the Community Benefits Agreement? Ratner’s promises of cheap seats to local fans?

Were there the political will, the public’s upside on the Nets’ sale could be negotiable, as well.

Could Ratner have held on?

The belated success of the Nets makes you wonder if Bruce Ratner, who lost big money on Atlantic Yards and saw his parent company upended and bought out, in part because of losses in Brooklyn, ever wonders if sticking with the Nets might have rescued his investment.

Ratner bought the money-losing New Jersey Nets in 2004, not because he expected to make money on the team, but because the scarce commodity of a professional team leveraged his plan to control public property and gain public assistance.

However, lawsuits and the 2008 recession delayed the move, so the Brooklyn Nets didn’t debut at the Barclays Center until after its September 2012 opening. That’s a lot of financial strain.

Revising the deals

So Ratner had to ditch original architect Frank Gehry, downsize the planned arena into a smaller, easier-to-finance venue, and decouple the four towers once planned to flank the arena.

The loss of Gehry meant the 20-year arena naming rights agreement, signed with the British bank Barclays in 2007 for $300 million, was cut to $200 million.

To get the arena built, Ratner in 2009 found Prokhorov and, in the next year, closed the sale of 80% of the Nets and 45% of the arena company.

By 2016, Prokhorov bought the rest of Forest City’s share, with the Nets valued at approximately $875 million and the arena company at $825 million. His cost: some $287 million, but only $54 million in cash, the rest in promissory notes.

Owning a basketball team is no core competency for a real-estate developer. Moreover, Forest City Ratner was part of publicly-traded Forest City Enterprises, which faced quarterly pressure to deliver rising profits, rather than position an irregular, money-losing investment for the long run.

Had Ratner had more staying power and prescience, and if his parent company had been privately owned and insulated from market pressures, including from hedge funds, perhaps he could’ve held onto the team (and arena company), ultimately reaping the profits that Prokhorov and Tsai could realize.

But that would’ve required a more significant investment in the team, and perhaps a willingness to absorb big contracts and thus losses.

Still, it’s tempting to think about it. Because, if thought of as a unit, the profits on the team and the arena company could, in fact, have helped deliver the project’s promised public benefits.

Now, with the ownership decoupled, that’s another failure of prescience.

Winners and losers

So, to recap, the big winner so far was Prokhorov, who didn’t need the money.

The second winner looks to be Tsai. Ditto.

Who knows, the third winner might be David Koch Jr., another billionaire.

The losers include Ratner, Greenland, and all the people who rallied for affordable housing only to see it delayed, and diminished, and all the elected and public officials who’ve failed to pursue a fair share, a better plan, and an accountable project. Plus the public at large.