A "No-Brainer": Cirrus Crows About Leveraging $200M of Discounted Debt to Control Atlantic Yards

The Real Deal asks: can Cirrus's union-built, workforce housing model work? Answer: maybe. Still, the speculator seems to have achieved a coup in Brooklyn.

On Feb. 2, the industry publication The Real Deal, which has followed Atlantic Yards steadily, published Can Cirrus build NYC workforce housing with union labor — and pension funding — at scale?, describing the fledgling financial firm’s three marquee efforts:

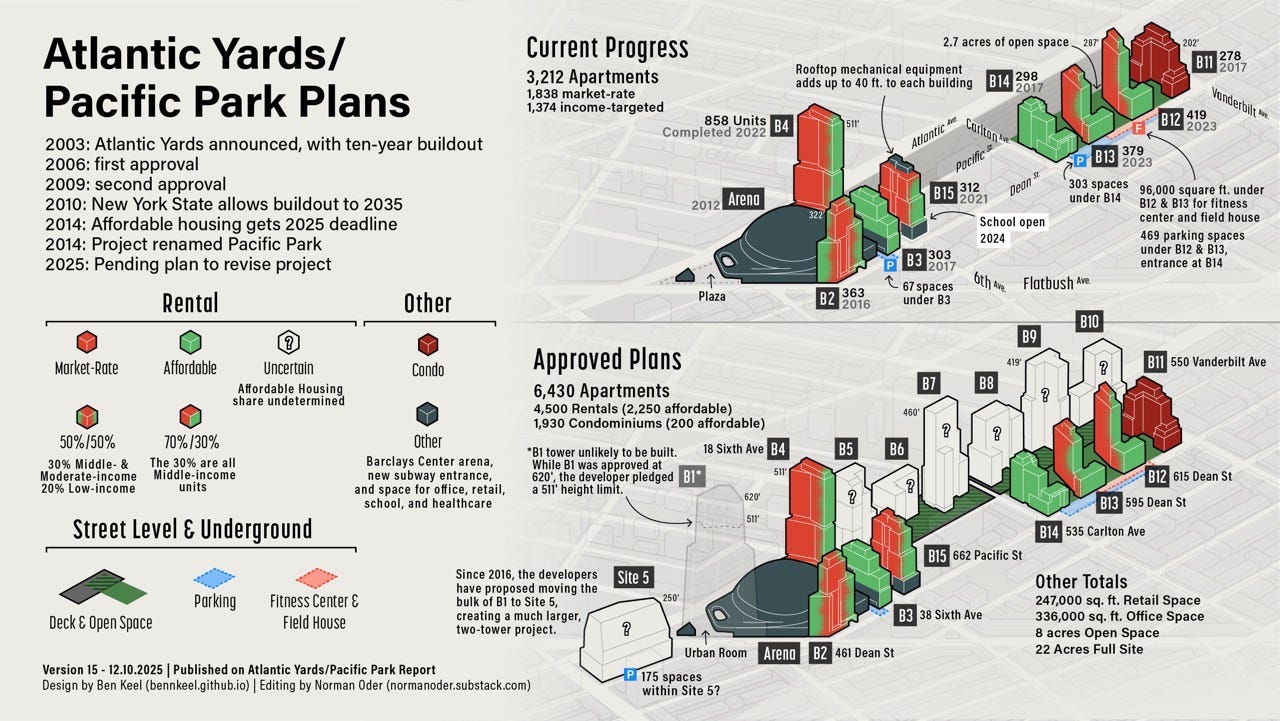

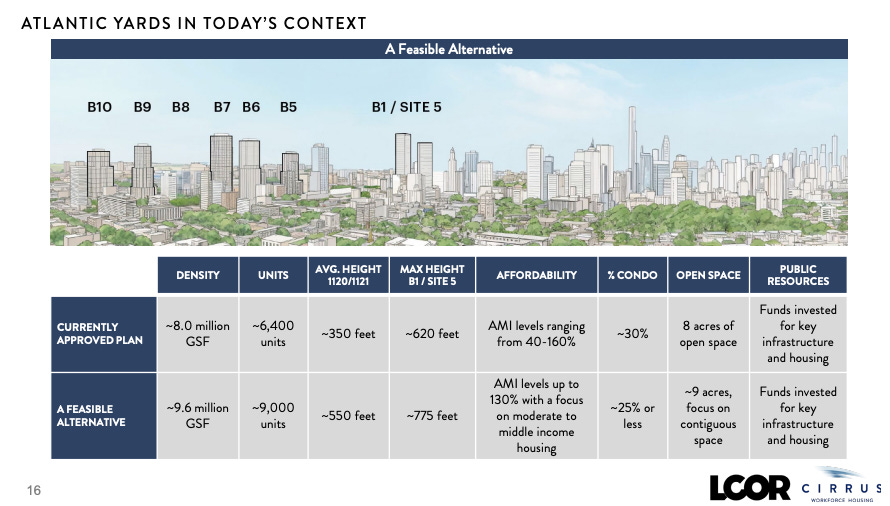

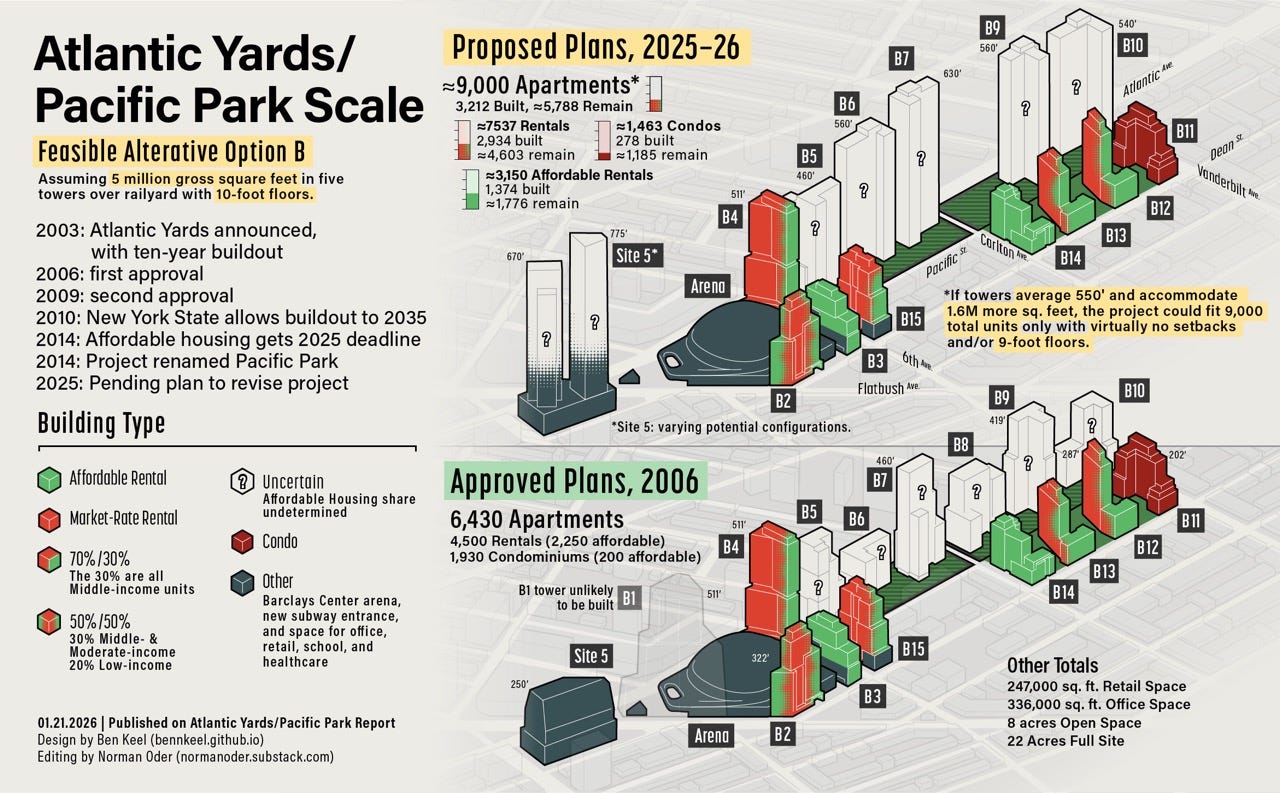

a proposal to build 2,570 more apartments at Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park, on top of the 6,430 approved, leaving 5,788 left to build

a plan, awarded (by Mayor Eric Adams’ administration) but not yet enacted, to build 3,000 units at the former Flushing airport site

a partnership with Resorts World New York City casino to build “up to 50,000 units”

Kathryn Brenzel’s reporting suggests we can’t yet answer the article’s headline question. (The first two plans involve funder Cirrus Workforce Housing working with the veteran development company LCOR.)

However, the article shows that Cirrus believes it got a huge bargain with Atlantic Yards, leveraging a relatively small investment into a potential huge payoff.

Framing the deal

The Real Deal (TRD) suggests that Cirrus Managing Partner Joseph McDonnell faced a big risk, given the stalled nature of Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park, with about half the buildings completed and an expensive platform needed before most future construction:

By late 2022, [developer Greenland USA] was in default on $350 million [actually, $286 million] in loans tied to the megadevelopment, and a year later the lender moved to foreclose on the site [actually, the six development sites over the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s Vanderbilt Yard].

It was hard to imagine who’d want to jump in and finish the job. Anyone replacing the developer… would have to lay out a new vision, get state approval, negotiate hefty fines and set new deadlines.

But Cirrus’ executives saw a salvage operation, and they purchased the debt.

“We thought it was a no-brainer,” McDonnell said during a recent interview in Cirrus’ Midtown office.

Why did they think it was a “no-brainer”?

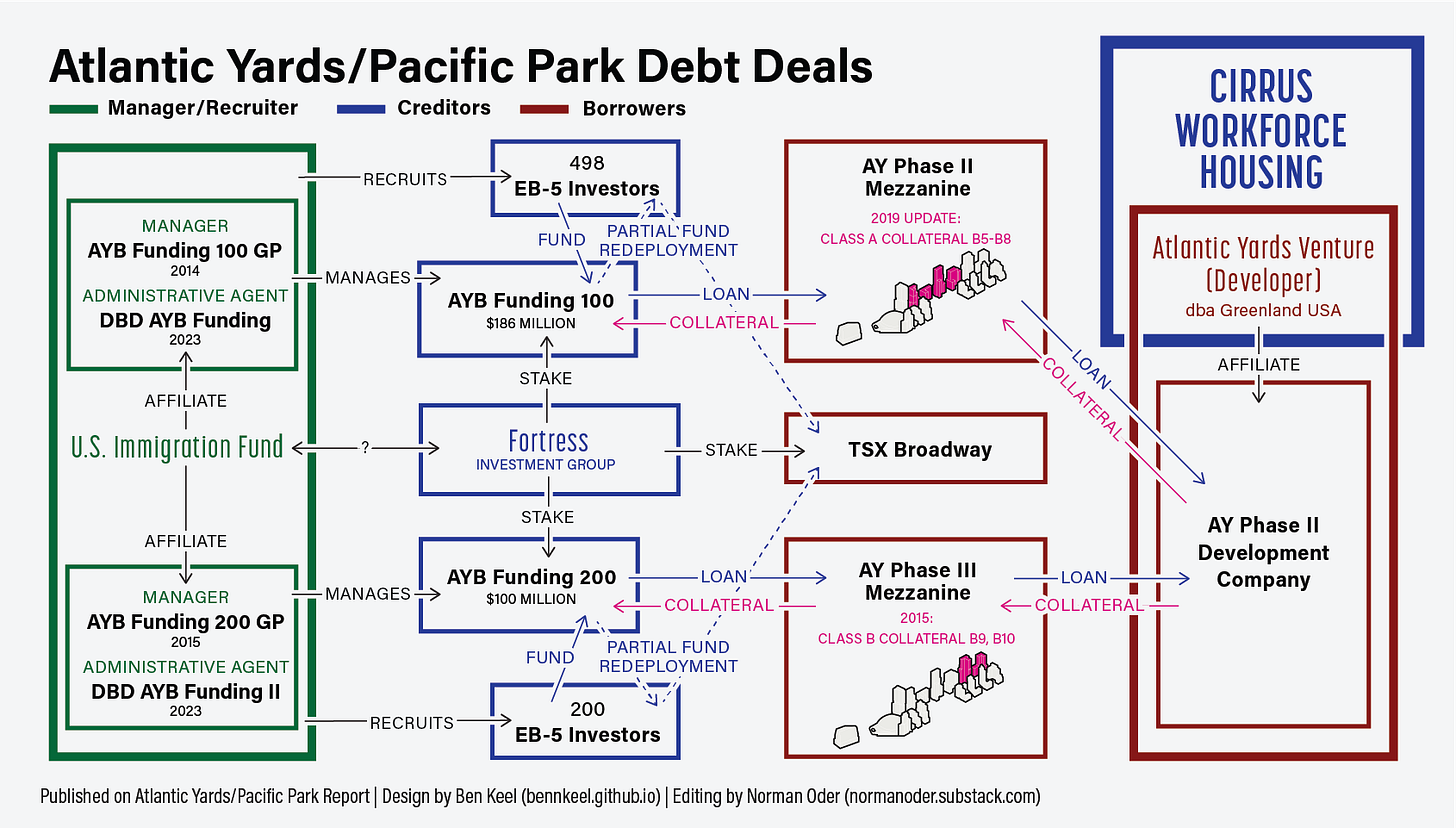

That’s not fully explained, but consider that Cirrus did not purchase the cited $350 [$286] million in debt, which was associated with two loans made by immigrant investors under the EB-5 cash-for-visas program. Rather, it bought separate debt, worth less.

For the EB-5 loans, the collateral was the right to build towers at six development sites, known as B5 through B10, which require a platform over the railyard, used to store and service Long Island Rail Road trains.

That debt was controlled, in the main, by the U.S. Immigration Fund, the middleman “regional center” that recruited the EB-5 investors and, thanks to advantageous contract language, left in charge as manager.

What Cirrus initially acquired, as the article’s link suggests, was the remainder of Greenland USA’s debt, valued at $200 million, associated both with Atlantic Yards and a project in Los Angeles known as Metropolis.

That purchase apparently gave Cirrus control of Greenland’s embedded Atlantic Yards investment, which McDonnell has said approaches $1 billion, which includes the new railyard and footings for a future platform, thus enabling future development.

Only later, last October, did a foreclosure auction of the EB-5 debt proceed, creating a new, Cirrus-led entity, but involving the other creditors.

Controlling the sites

The initial investment apparently afforded Cirrus senior rights to those six railyard development sites, as discussed below.

It also offered the unencumbered rights to build at two other valuable sites: Site 5, the parcel catercorner to the arena, as well as B1, the office tower once planned to loom over the arena.

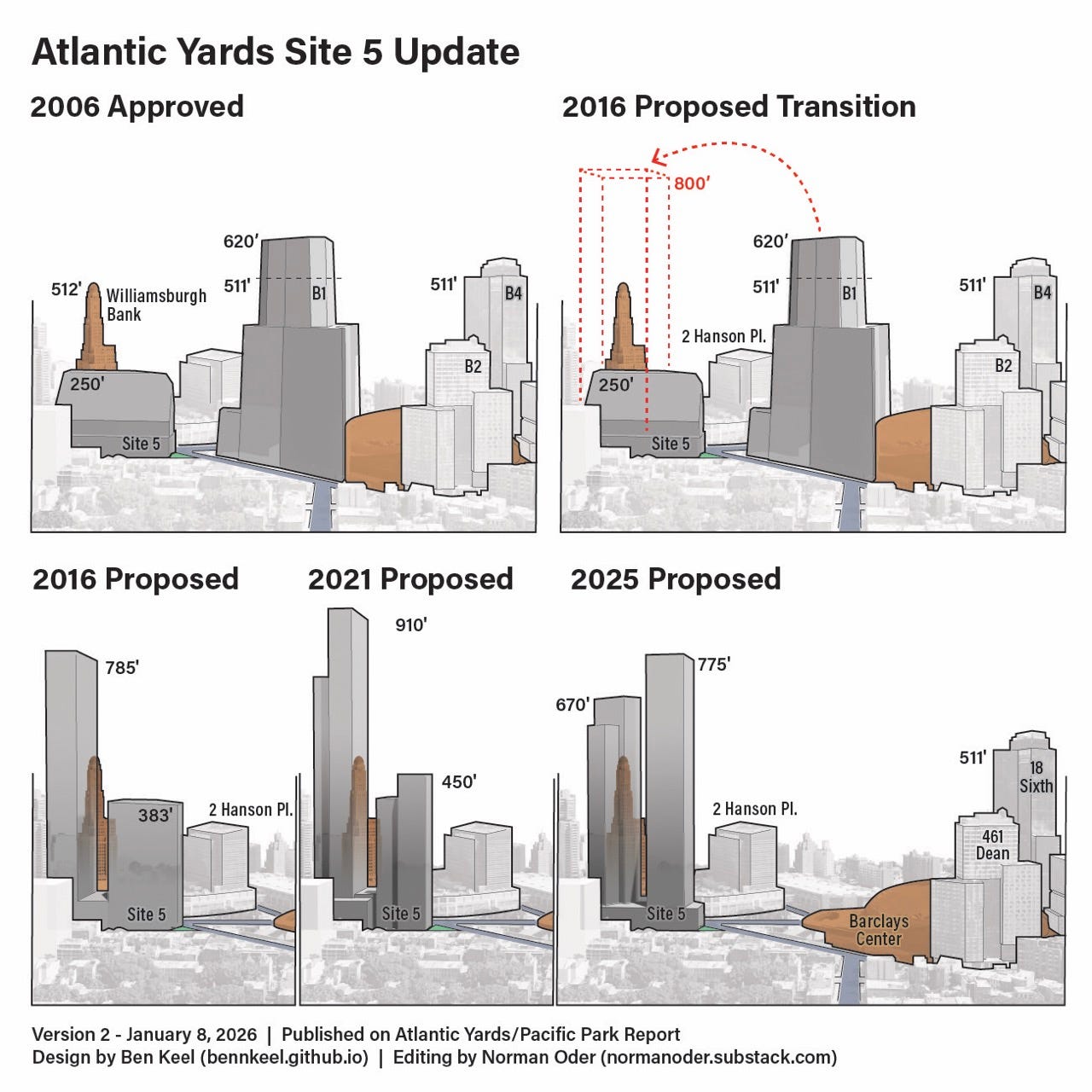

Since 2015-16, Greenland had aimed to transfer the bulk of B1 across Flatbush Avenue to Site, 5, creating a giant, two-tower project.

In October 2021, Greenland signed an Interim Lease memorializing that Site 5 project with Empire State Development (ESD), the state authority that oversees/shepherds the project, with the two towers as tall as 910 feet and 450 feet.

That site alone might be worth at least $250 million, I estimated, though that figure depends on how much below-market “affordable” housing is included and how much bulk is built.

More recently, Greenland has proposed an adjustment in the height of the two towers, but not the bulk.

Cirrus paid how much?

How much did Cirrus pay the banks that held Greenland’s $200 million in debt?

We don’t know, but it’s reasonable to think they got a major discount, perhaps 50% face value.1 If so, that means they put up $100 million.

Yes, Cirrus must make $11 million annual payments to the MTA for railyard development rights2, pay off Greenland USA’s other debts, hire consultants, and negotiate with government agencies. But that might not be too burdensome.

After all, ESD, rather than requiring Greenland, or its successors, to pay $1.75 million a month since June 1 for the 876 remaining units of affordable housing not built as required, has allowed Cirrus to negotiate payments totaling a modest $12 million.

That’s prompted outrage from local elected officials, and the coalition BrooklynSpeaks, which has already calculated a much higher figure.

Did ESD know how its gentle negotiating stance helped make a speculative deal a “no-brainer,” and allowed for significant proposed increases in scale?

An “asymmetric risk-return profile”

If Cirrus must invest less than $200 million to unlock Atlantic Yards, well, that sounds like a coup, especially they can navigate even more public assistance.

While McDonnell describes Cirrus Workforce Housing, backed by the pension funds of various (mostly construction) city labor unions, as “mission-driven,” it’s also an affiliate of Cirrus Real Estate Partners, which pursues “investments that offer asymmetric risk-return profiles and significant downside protection.”

This looks like a candidate.

Sure, there’s risk. Beyond the outlays described, Cirrus has had to negotiate with the state and with the holders of that $286 million in EB-5 debt, giving them an unspecified share in future proceeds.

And, yes, Atlantic Yards has encountered economic and political cycles, lawsuits, and the COVID-19 pandemic.

But there’s much upside. In fact, if Cirrus had simply acquired Greenland’s debt to unlock Site 5, that might have delivered a financial success. After all, ESD had already agreed to support Greenland’s two-tower plan.

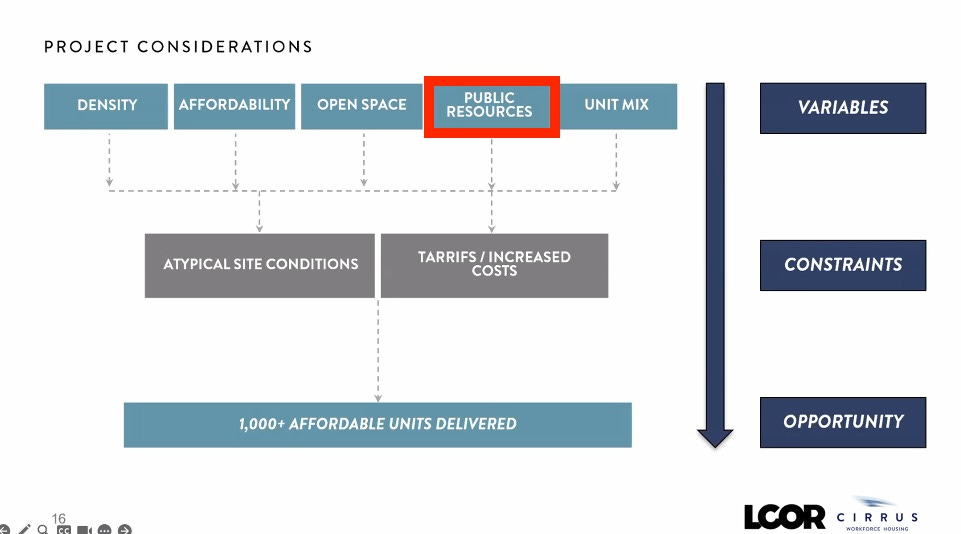

Instead, Cirrus has requested 1.6 million additional square feet of bulk for the railyard sites, worth perhaps $320 million, and is negotiating unspecified requests for “public resources” to assist with affordable housing and infrastructure (like the platform).

Meanwhile, though Cirrus’s McDonnell is affable and agreeable in public, the firm remains cagey. It hasn’t produced full renderings of its proposal. That’s why I commissioned the unofficial infographic above.

It has produced misleading images that enlarge the scale of the current plan, and downplay their proposal, as the link below suggests.

Though McDonnell claimed to TRD, “We’ve tried to bring a very realistic and transparent approach to this,” that’s not what the record shows.

How did Cirrus gain primacy?

We don’t know exactly how, by buying Greenland’s non-EB-5 debt, Cirrus gained primacy over the railyard sites.

Let’s consider the unofficial chart below, adapted from my previous coverage of the EB-5 deals, which did not assess Cirrus’s roles. Start at the right column.

The company Atlantic Yards Venture, owned by Greenland, controlled the subsidiary AY Phase II Development Company, parent of the entities AY Phase II Mezzanine and AY Phase III Mezzanine, which borrowed the EB-5 funds and offered the six railyard development sites as collateral.

Before Cirrus entered, that seemingly left power with the creditors: the EB-5 investors organized by the U.S. Immigration Fund, as well as periodic USIF partner Fortress Investment Group, which acquired part of the EB-5 debt.

But Cirrus, by acquiring Greenland’s remaining debt, gained control of Atlantic Yards Venture.

Did that leave Cirrus in ultimate control of AY Phase II Development Company, thus requiring the EB-5 debt holders to negotiate with them? Quite possibly, as I stated above, and as the unofficial flowchart suggests.

Even if the debt was not senior, Cirrus likely already had a structural advantage. By controlling Site 5 and B1, Cirrus had the upper hand with Empire State Development, which has said it preferred dealing with one development team, not two.

So if ESD welcomed Cirrus, that offered a signal to the remaining creditors, who finally agreed to the foreclosure.

Neither the USIF nor Cirrus could proceed on their own, but rather needed a partner—as Cirrus has with LCOR—with development experience.

Nudging out Related?

Still unexplained is why Hudson Yards developer Related Companies, which in 2024 was exploring a deal with the USIF to develop the railyard sites, withdrew, as announced a year ago.

Could it have been the complexity and cost of the challenge, compared with alternatives uses for their money, such as Phase 2 of Hudson Yards? Perhaps.

Or could it have been that, by acquiring Greenland’s debt, Cirrus had positioned itself as owning debt senior to the EB-5 collateral Related was seeking?

Remember, Related’s withdrawal was reported, by The Real Deal, just before the emergence of Cirrus. That indicates either that Cirrus had nudged Related out, or that Related had agreed to not discuss its departure publicly until the USIF found a new developer.

Relationship with LCOR?

The new article leaves several important business questions unanswered, so the public deserves to know more before ESD announces any agreement. A Memorandum of Understanding is expected to be signed by the end of March, with a potential extension through July.

We don’t know the nature of the relationship between Cirrus and LCOR, and how sustainable it might be. “We’re partners,” LCOR’s Anthony Tortora told me, but that doesn’t mean LCOR put up any money.

Tortora told TRD that he was connected to Cirrus via through a mutual friend at Plaza Construction, which—unmentioned—Greenland had earlier signed to work on the railyard platform.

Keep in mind that the joint venture Greenland Forest City Partners, involving Greenland USA and original developer Forest City Ratner, was once touted as a happy collaboration—until it wasn’t.

Relationship with USIF/Fortress

Nor do we know how much of a stake those holding the EB-5 debt now have in the project, and whether they have any decision-making power.

After all, they’ve arguably committed the most amount of capital, some $286 million, plus interest.

While McDonnell has said that Greenland, which retains some unspecified stake in the project, has a limited chance of financial recovery, he has not spoken similarly about the USIF and Fortress.

“That was a very difficult and challenging deal to do,” the USIF’s Nicholas Mastroianni II told The Real Deal. “I’d been negotiating with Greenland for five years, I couldn’t get them to move.” He and McDonnell knew each other, as Cirrus had previously made a loan to a USIF project.

It’s telling that, when interviewed by TRD, Mastroianni and McDonnell disagreed on who set up their early 2025 lunch to discuss Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park. That’s a credibility issue.

Also, consider that Mastroianni last October told TRD that the the project’s next phase might cost $4 billion and take five years—both questionable estimates, especially since he suggested that the second phase—with a more extensive, and expensive, platform—would cost only $2 billion.

Big picture: reasons for doubt

The Real Deal article raised doubts about Cirrus’s ambitious ventures.

After all, a rival bidder for the Flushing site questioned how Cirrus and LCOR could fulfill their promises given the team’s “glaringly absent track record of completing development projects.”

Indeed, Cirrus’s business so far involves providing financing. TRD described the firm’s office as having “the feeling of not being fully set up, with computer monitors propped up against empty bright white walls.”

Still, McDonnell and partner Anthony Tufariello say that in their careers they’ve overseen $150 billion in real estate finance transactions, $10 billion in real estate equity investments and more than 10,000 multifamily units.

Meanwhile, Resorts World, according to the state’s Gaming Facility Selection Board, has promised a maximum $25 million per year for a workforce housing fund, in partnership with Cirrus, “but the substance of the project is vague, with the promised investments in workforce housing to begin ‘in the immediate term.’”3 Cirrus told TRD no sites have been selected yet.

Last June, I noted that sponsored emails from two political publications both had the subject line “Resorts World is Delivering Workforce Housing for New Yorkers, Starting Now!” That’s a stretch.

As I wrote, if you follow the instruction to "Learn more about how Resorts World is helping put New Yorkers into housing here," the link goes to a press release announcing an agreement with Cirrus Workforce Housing to build "up to 50,000 units of workforce housing."

Also generating some doubt is Cirrus’s Kevin Gallagher, a former director of housing for the New York City Central Labor Council of the AFL-CIO, who connected the construction union pension funds to McDonnell and Tufariello.

One rival, John Crotty, told The Real Deal, “Him presenting himself as an affordable-housing person to the people of Brooklyn is laugh-out-loud funny.”

Big picture: reasons for belief

There are reasons to believe Cirrus has momentum. After all, it won rights to the Flushing site.

While a 2024 Cirrus Memorandum of Understanding with the city to build workforce housing does require negotiation with the new Zohran Mamdani administration, Mamdani’s key housing aide told TRD she wants to both work with the construction unions on workforce housing models and with the city and state comptrollers for other fund investments into housing.

So the role of construction union pension funds to finance such housing gives it a boost.

How affordable?

It’s worth noting that, at the most recent public workshop on Atlantic Yards, on Jan. 22, McDonnell modulated his rhetoric without making any hard promises, asserting that Cirrus would—contra earlier language—include low-income units.

He has said that that affordable housing plan will rely on available subsidies. Indeed, as highlighted below, “public resources” are key.

That formulation is a little too pat.

Why exactly should the public rely on it? Why can’t public agencies consider the developer’s cost basis and expected returns? Why can’t third-party analysts represent the public interest?

Brooklyn Ascending?

The company name derives from high-altitude cirrus clouds, and McDonnell told TRD that Cirrus invests in the country’s top markets, “where buildings tend to be taller.”

Unmentioned: they call their Atlantic Yards partnership Brooklyn Ascending Land Co., with numerous affiliates using the name “Brooklyn Ascending.”

Well, they’re not modest.

Atlantic Yards an outlier?

The Real Deal reported:

Though Cirrus still buys overleveraged loans and takes over properties, McDonnell said he doesn’t consider Cirrus to be in the business of “distressed debt,” and that the company prefers to work out solutions for borrowers.

Wait a sec. Atlantic Yards is a big bet on “distressed debt”!

At a press conference in June, Gib Veconi of BrooklynSpeaks said there was no justification for waiving the affordable housing penalties.

“The other parties in the deal are investors who have been speculating in the distressed debt of the current developer,” he said. “They’re sophisticated people. They understood that they were taking on something that has risk and liability in the form of these liquidated damages.”

It’s likely Cirrus bought Greenland’s debt before fully negotiating with Empire State Development over the penalties.

If that was a “no-brainer,” well, perhaps Cirrus recognized that, even if it only built at Site 5, it could achieve an “asymmetric risk-return profile.”

Then, if it aimed for more, it had significant leverage with both the other creditors and New York State.

This European distressed debt specalist suggests, “Distressed real estate investments typically offer 30-70% discounts below market value.” It’s plausible that Cirrus paid more than 50 cents on the dollar, but it’s also plausible it paid less.

This relates to a deal, reached in 2005 and revised in 2009, for the airspace above the railyard. Cirrus apparently expects 1.6 million additional square feet of development rights at no cost.

This is described more briefly by TRD: “In New York, the board charged with reviewing applications for state casino licenses urged gaming officials to closely track all commitments made by the three winning teams — including the housing pledge made by Resorts World, which it described as vague.”