Who's the "Lender"/Creditor Now? Who Controls the EB-5 Loan Collateral?

The future of six development sites relies on murky transactions involving the developers, immigrant investors, the U.S. Immigration Fund, & Fortress Investment Group.

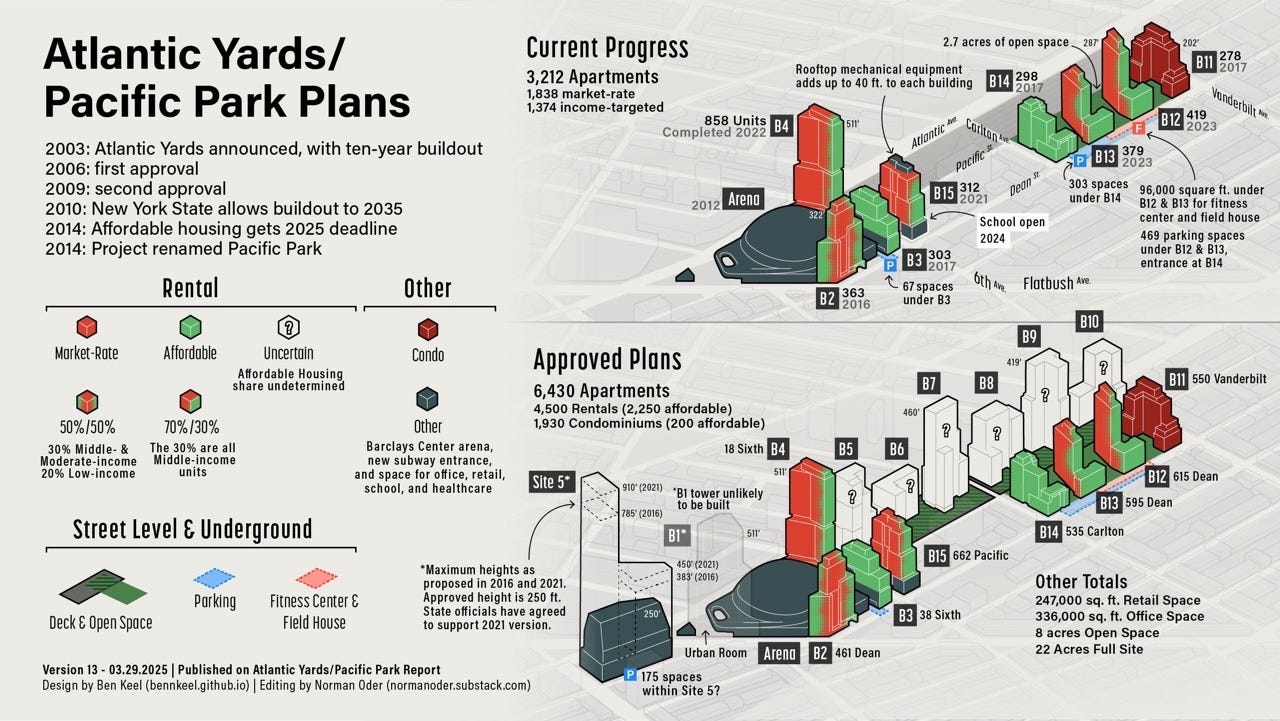

Since six Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park development sites—most of the remaining project—entered foreclosure in November 2023, with no resolution in sight, public discussion has concerned the mysterious “lender,” which somehow controls the project’s fate.

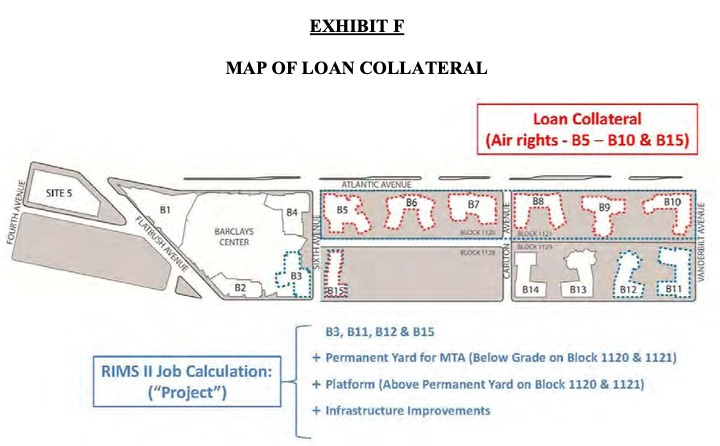

That’s because the “lender” received, as collateral for two loans to developer Greenland Forest City Partners (now Greenland USA), rights to six parcels (B5-B10) over the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s sunken Vanderbilt Yard.1

Those parcels can’t be developed into towers, and supply the project’s remaining 5.3 acres of open space, without an expensive platform to protect the railyard, used to store and service Long Island Rail Road cars.

Also, only when the “lender” forms a joint venture with a “permitted developer”—one with at least a decade of experience on large projects—can any development go forward.

That won’t be simple. It surely will trigger a renegotiation of terms, including the pending May 31 deadline, with $2,000/month penalties for each missing unit, to deliver the remaining 876 apartments. A new developer likely will want additional valuable square footage, as Greenland once sought.

Who’s the “lender”?

Despite shorthand in news coverage and at public meetings, the U.S. Immigration Fund (USIF)—a private company that recruits immigrant investors under the EB-5 investor visa program—isn’t exactly the “lender,” though it may control (or may have controlled) the lending entity and now may be a creditor, with a stake in that entity.

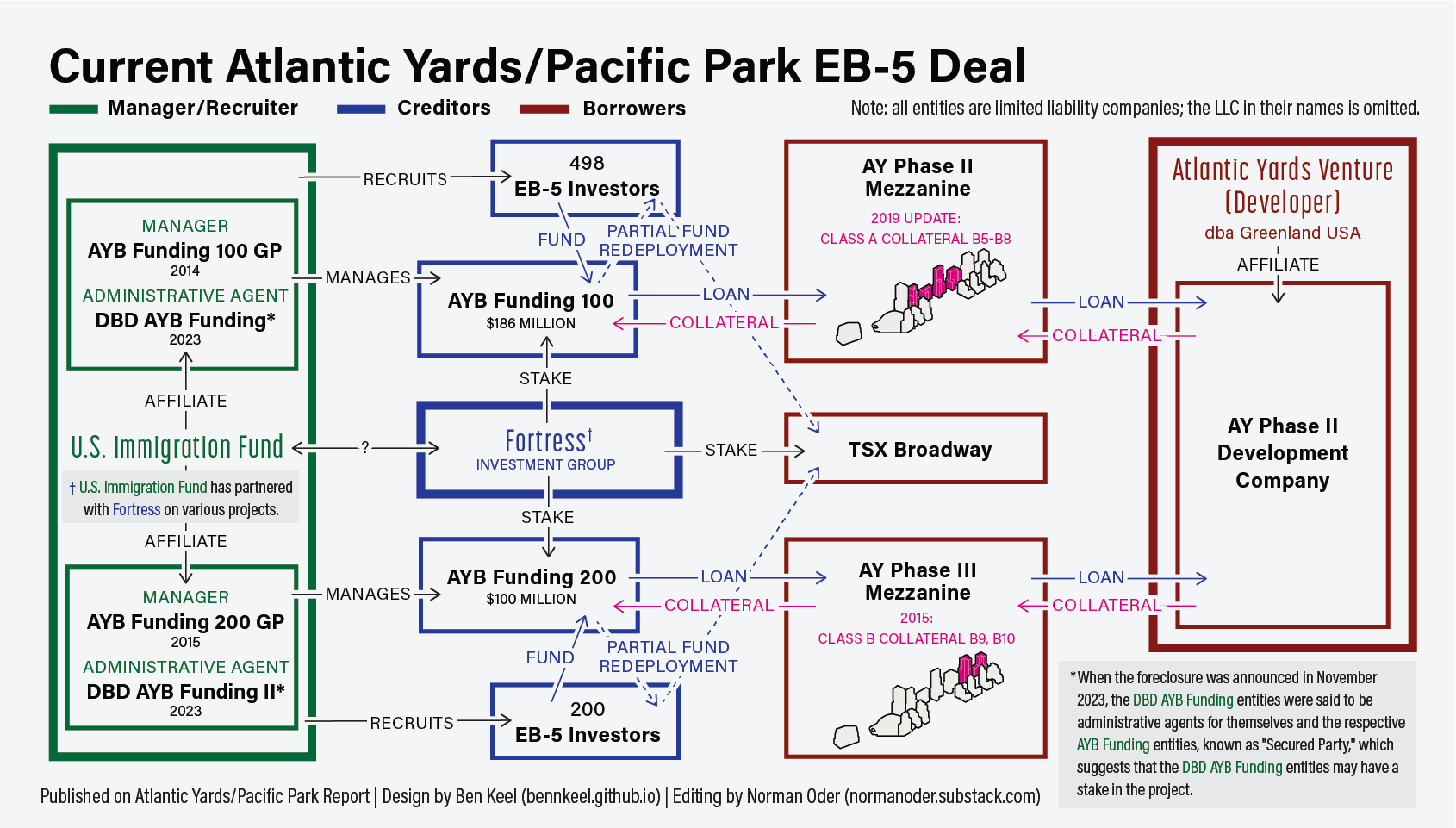

That’s my conclusion after reviewing project-related documents, as distilled in a series of five flowcharts, created with my collaborator Ben Keel. So this article updates and clarifies some of my previous coverage that didn’t fully acknowledge the apparently increased stake for both the USIF and its periodic partner Fortress Investment Group.

The fifth and final flowchart, below, hints at the complexity. Don’t try to make sense of it until you see the full sequence. (I recommend you read this article on a desktop, to take advantage of the wider width option for the graphics.)

The USIF is a “regional center,” a private company approved to recruit investors, assemble the deals, and form a new commercial enterprise to loan money to a real-estate project. Each deal involves a cascade of separate limited liability companies (LLCs) that shield each participant from the others’ debts.

USIF affiliates play many roles: recruiter, manager, administrative agent, and, perhaps, stakeholder.

Given the complexity, public discussion often defaults to shorthand. That ignores the immigrant investors from China who put up $500,000 each, have (mostly) not been repaid, and, because of dubious contract drafting, have little sway in managing their investment.

Press shorthand

“Greenland borrowed the money in 2014 from Nick Mastroianni’s U.S. Immigration Fund,” the Real Deal reported Nov. 27, 2023, adding that “Fortress Investment Group purchased a stake in the debt in 2020.”

However, as the flowcharts show, the money was borrowed by entities created by the USIF—though a USIF affiliate may now have a stake in the debt. While Fortress acquired a stake, it’s unclear whether that was via a purchase. (Fortress is owned "mainly by Abu Dhabi-based sovereign-wealth fund Mubadala Investment.")

“Nick Mastroianni’s U.S. Immigration Fund, which had raised capital through the EB-5 program, moved to foreclose on the sites,” the Real Deal reported Dec. 10, 2023. Actually, the entities pursuing foreclosure were USIF affiliates known as DBD AYB Funding and DBD AYB Funding II, not previously disclosed in any project documents.

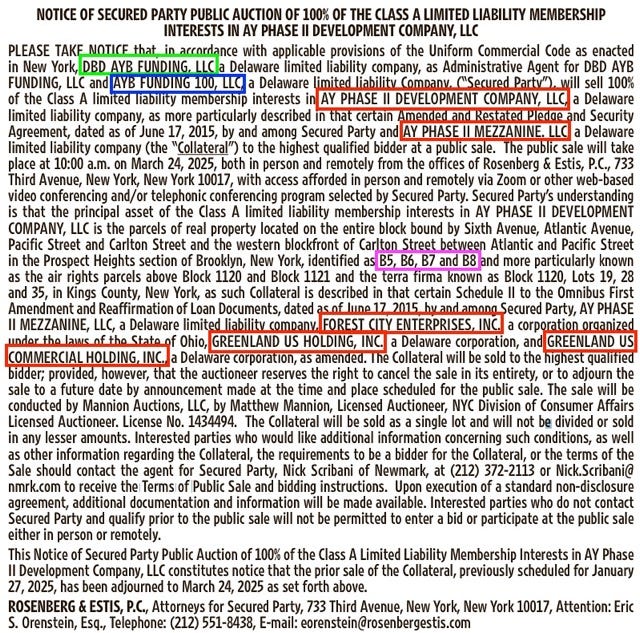

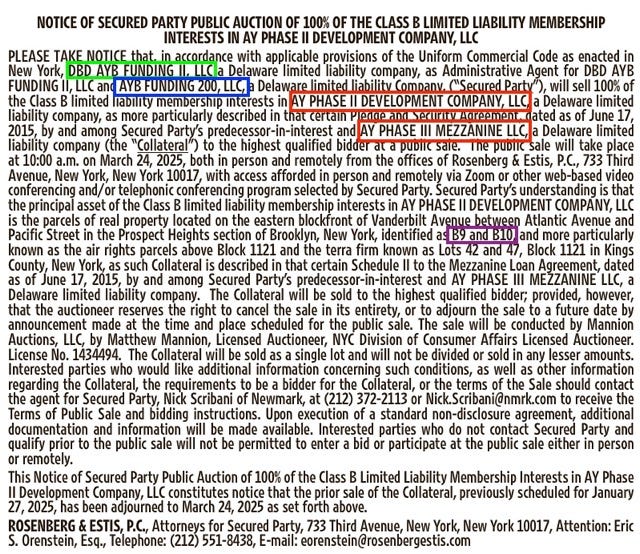

The first advertisement, below left, cites the auction of the Class A limited liability membership interests (four development parcels) in AY Phase II Mezzanine, an entity affiliated with developer Greenland. The second, on the right, cites the auction of the Class B interests (two development parcels).

Using similar shorthand, the Wall Street Journal reported Aug. 27, 2024, “About $300 million in debt on the site is held by the U.S. Immigration Fund and by Fortress, a big investment firm.”

Public discussion

The public discussion has been muddy.

At a meeting last June, members of the (purportedly) advisory Atlantic Yards Community Development Corporation (AY CDC) were told of progress by a representative of Empire State Development (ESD), the state authority that oversees/shepherds the project.

ESD "is being presented with a plan for a new developer to be brought in," said AY CDC President Anna Pycior, who serves as ESD's Senior VP, Community Relations. "Negotiations are ongoing. The parties are talking with the lender about bringing in new development partners."

But the "lender,” I wrote last August, was the manager of a fund created not from his own company's assets, but from the immigrant investors. I suggested that Nicholas Mastroianni II—with questionable past—be called "the guy in control of the lender."

That structure was created by contract language that advantaged the manager over the investors. However, a USIF entity may now be a creditor, along with Fortress and the original investors, their stake diminished. In other words, while USIF didn’t put up the money, Mastroianni now may have a claim to the collateral.

Official chart, 2014

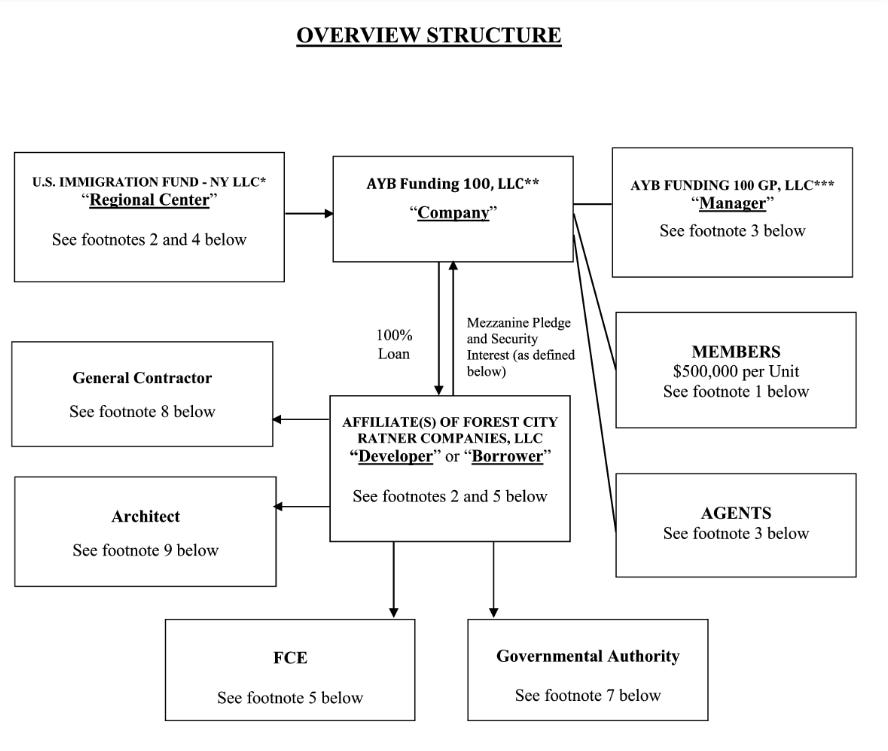

Let’s look at the purported Overview Structure for the 2014 EB-5 loan, marketed2 as “Atlantic Yards II”: $249 million from 498 investors to AYB Funding 100, which would then loan the money to affiliates of the developer, then Forest City Ratner but soon to become Greenland Forest City Partners.

The screenshot, taken from the private placement memorandum (PPM), is jam-packed with irrelevant parties. The project’s general contractor and architect, as well as the migration agents who recruited the investors, are not crucial to the loan.

Moreover, though “Governmental Authority” links to a footnote explaining that this project is sponsored by ESD, a state authority, and includes involvement by New York City, neither was party to the loan. So that citation misleadingly suggested greater stability.

What was the collateral?

The PPM also included the graphic below, outlining the collateral: rights to build at six development sites (B5-B10) over the railyard, plus B15, across Sixth Avenue from the arena.

Unofficial flowchart 2014

Let’s revise the above charts. Below is an unofficial flowchart created with designer and data analyst Keel, based on both the PPM and a Sept. 9, 2014 Consent Letter from Empire State Development (ESD), the state authority that oversees/shepherds the project.

On the left, as in the other new flowcharts, are entities connected to the U.S. Immigration Fund. Not only did the USIF recruit the investors in AYB Funding 100, it controls the manager, AYB Funding 100 GP, a connection missing from the chart shown investors.

We even include the managing member of AYB Funding 100 GP, though that will be omitted on some charts. Just remember: within the nesting dolls of USIF LLCs, Mastroianni is a consistent signatory.

The outline at center-right indicates the collateral. At far right are entities connected to the developer. Again, all are LLCs, so the failure, for example of AY Phase II Mezzanine to repay the $249 million would mean the lenders/creditors could only go after the collateral, not the larger company’s assets.

Official chart, 2015

Below is the official Transaction Structure for the 2015 EB-5 loan, from the related Private Placement Memorandum. Marketed as “Atlantic Yards III,” it raised $100 million from 200 investors, forming AYB Funding 200.

It’s far simpler than the purported 2014 structure, since it omits unrelated third parties. However, the design, focused on the transaction between the Company (lender) and the Developer, leaves the misleading impression that AYB Funding 200 GP, the manager, is not affiliated with the USIF.

Moreover, while accurately describing the collateral as the right to develop B9 and 10, the chart obscures a key change: the collateral had been diluted.

Unofficial flowchart 2015

The unofficial flowchart below, created with Keel, includes both the 2014 and 2025 transactions, respectively, moving horizontally from the top and bottom left. This is based on both the PPM and a June 17, 2015 Consent Letter from ESD.

The key change is in the column center-right, which shows how the collateral was diluted.

While in 2014, six development sites were offered as a collateral for a $249 million loan, in 2015 two sites (B9, B10) were severed to serve as collateral for a new $100 million loan. That left four sites (B5-B8, B15) to collateralize the original loan. There would now be a Class A interest and a Class B interest.

That might have been a warning regarding the loan’s precariousness for both investors and state officials. Still, it’s not hard to “shop” for a favorable appraisal, so I suspect the USIF got—or would’ve been able to get—an appraisal confirming that the Class A collateral still supported the $249 million loan.

Unofficial flowchart, 2019

The situation got more complicated in 2019, because the developer—by then almost completely Greenland USA3—sold the lease to the B15 site to The Brodsky Organization for $55.83 million.

So B15 could no longer collateralize the Class A interest, reducing the collateral to the sites B5-B8. The investors in AYB Funding 100, however, received an inflow of $63.16 million, not $55.83 million from AY Phase II Mezzanine.

Why? That subtraction was necessary to maintain an 80% loan-to-value ratio, a typical ceiling required in lending, as a higher ratio compounds risk of default.

When asked by developer Greenland to release the lien on B15, the USIF, investors were told, “conducted due diligence to determine whether the sale of B15 would cause the borrower to be out of compliance with the terms of the Loan Agreement, including the important loan to value ratio of 80%.”

A third-party appraisal, investors were told, determined that the borrower “partially repay the EB-5 loan, in an amount equal to the appraised value of the released parcels,” or $63.16 million.

That should have been a red flag, too. Brodsky’s payment was 11.6% less than the appraised value, which suggests that the collateral was overvalued, making the loan risky. If investors had been repaid only $55.83 million, the remaining loan would’ve represented more than 80% of the appraised value.

The need for redeployment

Most investors, however, couldn’t keep the money. Unless they already had seen their conditional residence transformed into a permanent one, they were required to keep their money “at risk,” according to the EB-5 rules at the time.4

Unless they left the EB-5 program completely, they now had to move about $126,000 of their $500,000 investment to one of four options offered by the USIF.

Those included a "blended investment" model into hotels, housing, and mixed-use projects; an office building in Manhattan; a hotel/retail/theater/signage project in Times Square known as TSX Broadway; and a hotel in Miami’s South Beach.

The latter two were projects involving Fortress. It’s unclear how much of the $63.16 million went into each investment.

Unofficial flowchart, 2020

The situation got further complicated in late 2020, after the pandemic began. The USIF encouraged investors in AYB Funding 100 to move up to $150 million to TSX Broadway and those in AYB Funding 200 to move up to $50 million.

The USIF offered both a carrot and a stick. The carrot was a purportedly better investment, based on economic conditions and risks.

The stick was a warning that Fortress would be in control. For example, the AYB Funding 100 investors were told that, on the purchase and sale of “a portion” of the loan, Fortress would be the “majority owner” and would “control all major decisions affecting the EB-5 Loan and the collateral,” which could means the original investors would lose their investment “in a default, restructuring or foreclosure scenario.”

It’s unclear how Fortress could become the majority owner of each loan without acquiring a majority, though that might reflect contract language crafted by the USIF. Note that we now title the second column from left “Creditors” rather than “Lenders,” since those owed money may not have put up the money.

It’s also unclear whether Fortress purchased portions of each loan by investing cash in each LLC, or whether it acquired its stake via a swap of obligations or a more convoluted deal.

The scenario provokes skepticism: If TSX Broadway was, as USIF contended, a more solid project than Atlantic Yards, why would Fortress move extra cash to the Brooklyn project? Either TSX was unsteady—indeed, it would crash—or Fortress saw and advantageous. Maybe both.

It’s unclear how much of the EB-5 investors’ money was moved to TSX.

Unofficial current flowchart

That brings us to today. The flowchart below shows where things might stand, with considerable uncertainty regarding how much of the AYB Funding entities are owned by Fortress, the original investors, or a USIF affiliate.

These are questions New York State officials should get answered.

As noted above, upon the 2023 foreclosure filing, we learned of two new USIF entities. DBD AYB Funding (for the first loan) and DBD AYB Funding II (for the second loan). These so-called administrative agents were cited in the foreclosure notices. It’s unclear whether they have supplanted the manager or simply work with the manager.

DBD does what?

But they may have a more significant role. The notice for the first foreclosure, for example, says DBD AYB Funding is “Administrative Agent for DBD AYB FUNDING and AYB FUNDING 100 (Secured Party).”

That’s not easy to parse. Why say DBD AYB Funding is the administrative agent for itself unless the entity has some greater role? Are DBD AYB Funding and AYB Funding 100 both secured parties—i.e., those with rights to the collateral? Are they a single secured party?

The DBD entities likely have some stake in the project. Last year we learned that the required annual payment to the MTA for railyard development rights, previously made by Greenland USA, was made by the DBD entities, according to the MTA.

How they could take over that role remains unclear, especially since the foreclosure has been stalled. But only an entity with a financial stake in the future railyard parcels would make such a payment. That would make USIF, if not the “lender,” among the “creditors.”

Big questions pending

If the AY CDC is supposed to advise the parent ESD on the project, well, shouldn’t they know who owns what, and how much?

At a March 25 meeting, as I reported, ESD officials seemed a little fuzzy. “If we're looking forward, anything that we get,” said Joel Kolkmann, Senior VP, Real Estate and Planning, “will be reviewed in terms of Fortress’s involvement, USIF’s involvement, their breakdown in the entities, their ownership… What we know now is that Fortress has a percentage of debt with USIF, and that's the extent of what we have.”

At the next AY CDC meeting, surely before the May 31 deadline, we should learn more:

Who owns what, and how much?

What are the roles of the USIF entities?

How did a USIF affiliate pay for railyard development rights?

Big money at stake

While Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park was presented, albeit without great credibility, by original developer Forest City Ratner as a civic-minded project promising “Jobs, Housing, and Hoops,” today, shadowy entities like the USIF and Fortress, which have never answered questions in public, are surely focused on the deal and the dollars.

And if the USIF has managed to transform from manager of an EB-5 investment to stakeholder, along with Fortress, well, it wouldn’t be the first time.

That scenario happened when Mikhail Prokhorov shuttered the Nassau Coliseum in 2020, leaving the venue’s lease in the hands of the “lender”—er, creditor—the EB-5 fund that lent $100 million to renovate the venue.

Mastroianni, though, gained control of the lease after forming Nassau Live, with a 25% stake from Fortress in 2021. (Did Fortress enter via a swap of EB-5 investor funds into a Fortress project?)

In October 2023, Newsday reported that Las Vegas Sands, pursuing a casino bid, paid Nassau Live $241 million to acquire the lease, including a site nearly 70 acres. That’s an extraordinary profit.

Fortress, aiming to outpace conventional investments, makes big bets. As I noted last September, the Real Deal described Fortress as having “a reputation for getting involved in hairy projects that scared others away.” In one condo deal, a Fortress executive crowed, "We stole a building in broad daylight."

Atlantic Yards may be a less audacious deal. But it likely will be advantageous, especially if entities charged to represent the public interest don’t look deeper.

The original collateral included an additional development site, B15, on terra firma, but a lease to that parcel was later sold, and the collateral removed, as explained further in this article.

Though it was was the first loan with investors recruited by the USIF, it was marketed in China as “Atlantic Yards II,” since “Atlantic Yards” was already a brand name on the EB-5 market. A separate EB-5 investment was marketed in 2010 by the New York City Regional Center; the $228 million borrowed was eventually, albeit belatedly, paid back.

In 2018, Greenland took a 95% share in Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park going forward, with Forest City later giving up any stake in the B4 and Site 5 projects. Forest City was absorbed by Brookfield Asset Management, which retains, a spokesman said in November 2023, a “nominal” stake.