Welcome to "The Brooklyn Trio"?

In architecture firm's presentation, developer Greenland lobbied hard to build bigger at Site 5 opposite arena. New York State signed on. Tower images still redacted.

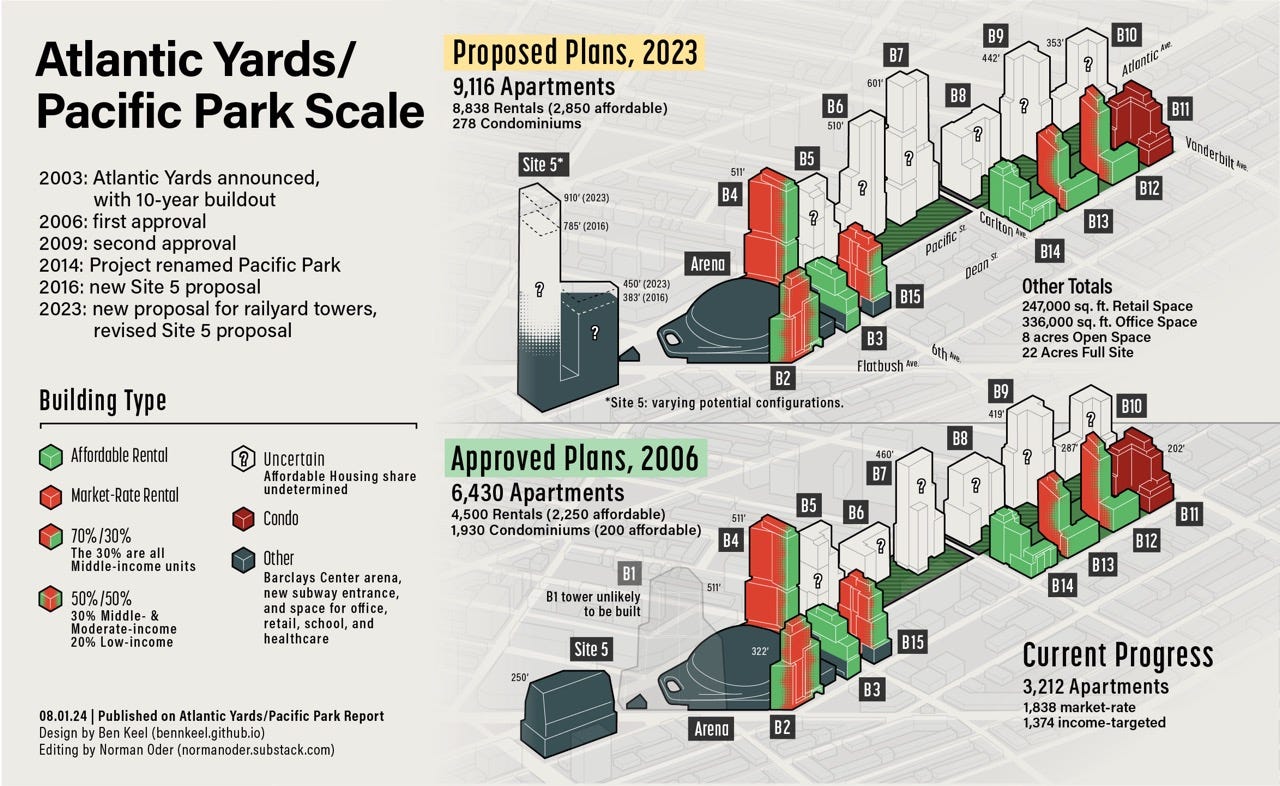

How might the developers of Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park justify their request to build the second-tallest tower in Brooklyn?

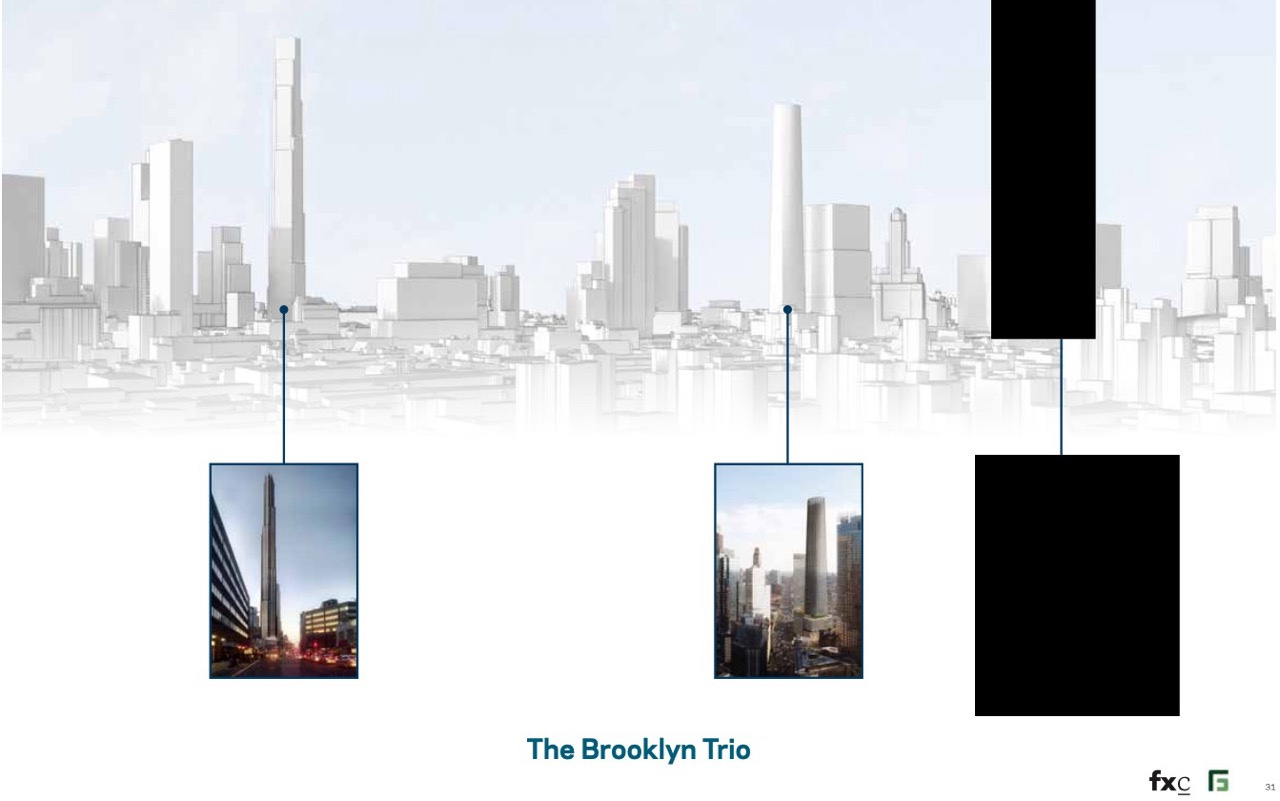

Well, according to a presentation made to state officials in November 2018, a 910-foot tower at Site 5, the parcel catercorner to the Barclays Center, would be part of “The Brooklyn Trio,” including the borough’s sole supertall, The Brooklyn Tower, and the planned 840-foot tower at The Alloy Block, formerly known as 80 Flatbush.

Whether the three towers, assuming they’re all built, comprise a trio surely depends on the perspective.

The perspective provided in the presentation above, by FX Collaborative for current master developer Greenland USA, seems from a helicopter hovering over Gowanus, not exactly a view most Brooklynites would experience.

Note that the outline of the building, surely not minutely detailed, was redacted by Empire State Development (ESD), the state authority that oversees the project, when it responded to my Freedom of Information Law (FOIL) request.

The justification: commercial information “which if disclosed would cause substantial injury to the competitive position of the subject enterprise.” Really?

In October 2021, ESD signed an interim lease for Site 5, agreeing to support the developer’s request for a larger project, with towers 910 feet and 450 feet and bulk of 1.242 million square feet, enabled by a bulk transfer from the unbuilt flagship tower (B1), once slated to loom over the project.

Brooklyn advocate Gib Veconi, a leader of the BrooklynSpeaks coalition and a member of the Atlantic Yards Community Development Corporation advisory board, got the document after his own FOIL request and tweeted slides, noting, “The agency has redacted images of the design to which it agreed, claiming they are a trade secret.”

Note that Greenland, which is losing six railyard sites to foreclosure, likely wouldn’t build at Site 5 by itself but rather sell the site or former a joint venture.

A joint venture involving Related Companies is negotiating with ESD over the railyard sites. Greenland previously sought to increase the bulk there, as well, as I reported.

Evolving plans

In 2006, Site 5, longtime home to the big-box stores P.C. Richard and (now-closed) Modell’s, was approved for a 250-foot tower, with about 440,000 square feet. The 620-foot B1 tower, which original architect Frank Gehry dubbed “Miss Brooklyn,” was slated to loom over the arena.

Upon final approval, developer Forest City Ratner agreed to lower the height of the building to 511 feet, symbolically one foot shorter than the iconic Williamsburgh Savings Bank tower, but with more than three times the bulk.

During the recession, Forest City ditched Gehry’s plan and downsized the arena, choosing a design by Ellerbe Becket, later amended by SHoP. Building the Barclays Center, Forest City decoupled the four towers from the arena rather than building them simultaneously, in part because it lacked an anchor tenant for B1’s office space.

In 2015-16, the joint venture Greenland Forest City Partners, then the developer, recognized that it could not build the flagship tower with an operating arena.

(I wouldn’t be surprised if Forest City had earlier agreed, when selling the arena company to Brooklyn Nets owner Mikhail Prokhorov, to never build B1.)

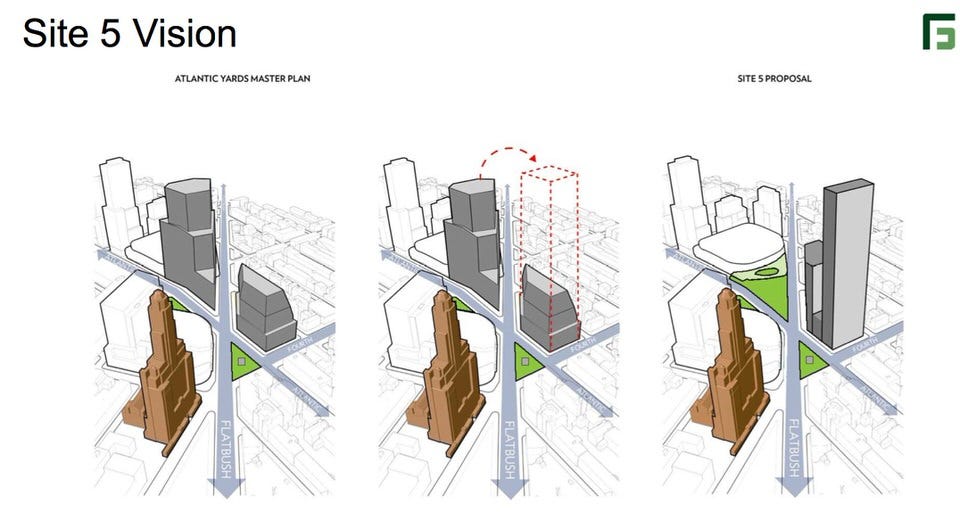

Forest City proposed to move B1’s bulk to Site 5, creating a giant, two-tower project, with the taller tower 785 feet and about 1.142 million square feet. In 2021, as I reported, Greenland—then without Forest City—got ESD to support an even larger plan.

Before I got the FX Collaborative presentation, I commissioned graphic designer Ben Keel to produce an image of the two Site 5 proposals.

The image is unofficial and not from street level. The public should have a variety of perspectives from which to evaluate the proposals. Would the new taller tower block the view of the Williamsburgh Savings Bank tower? Surely from some angles.

Note that in October 2019, the ubiquitous (for ESD) environmental consultant AKRF was hired to produce a Technical Memorandum regarding modifications to the General Project Plan, likely papering away any untoward impacts.

Source of the FX document

In my Aug, 1 article describing how Greenland USA sought to rescue Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park by supersizing it, I noted an October 2021 Interim Lease for Site 5, memorialized an expansion plan described in Exhibit K.

That document referred to a “design intent” prepared by FX Collaborative, so I requested it. Here’s the full presentation, which I’ve excerpted significantly below.

Advocacy document

Even without images of the proposed building, the presentation is a remarkable advocacy document, portraying the currently approved plans as a nightmare, while papering over the business decision to not build B1 and the fact that a key beneficiary, the arena operating company, would then get the plaza for free, with no reciprocity.

The redactions keep us from evaluating the proposed plans, but, given what’s been shared, any plans should be taken with a grain of salt.

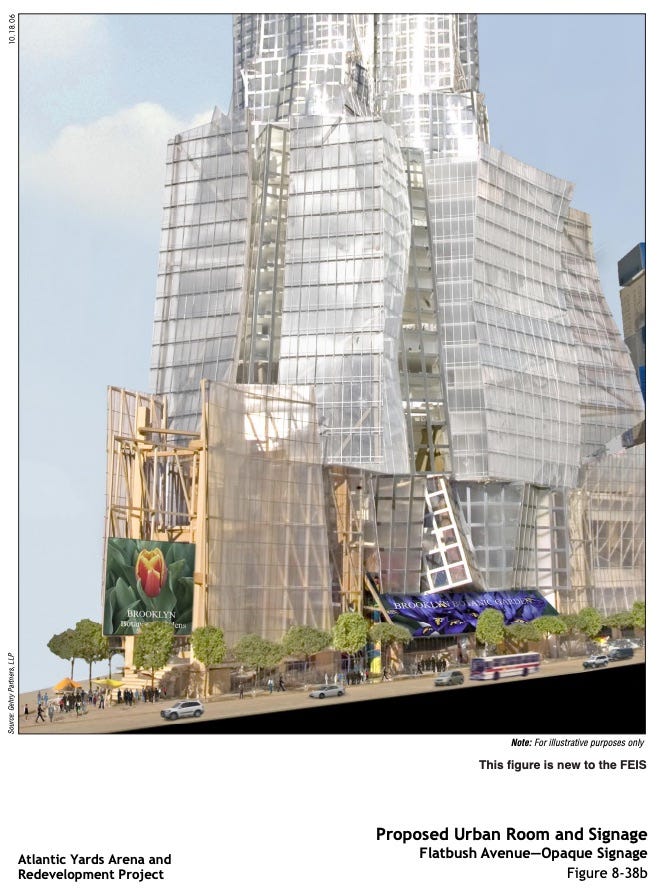

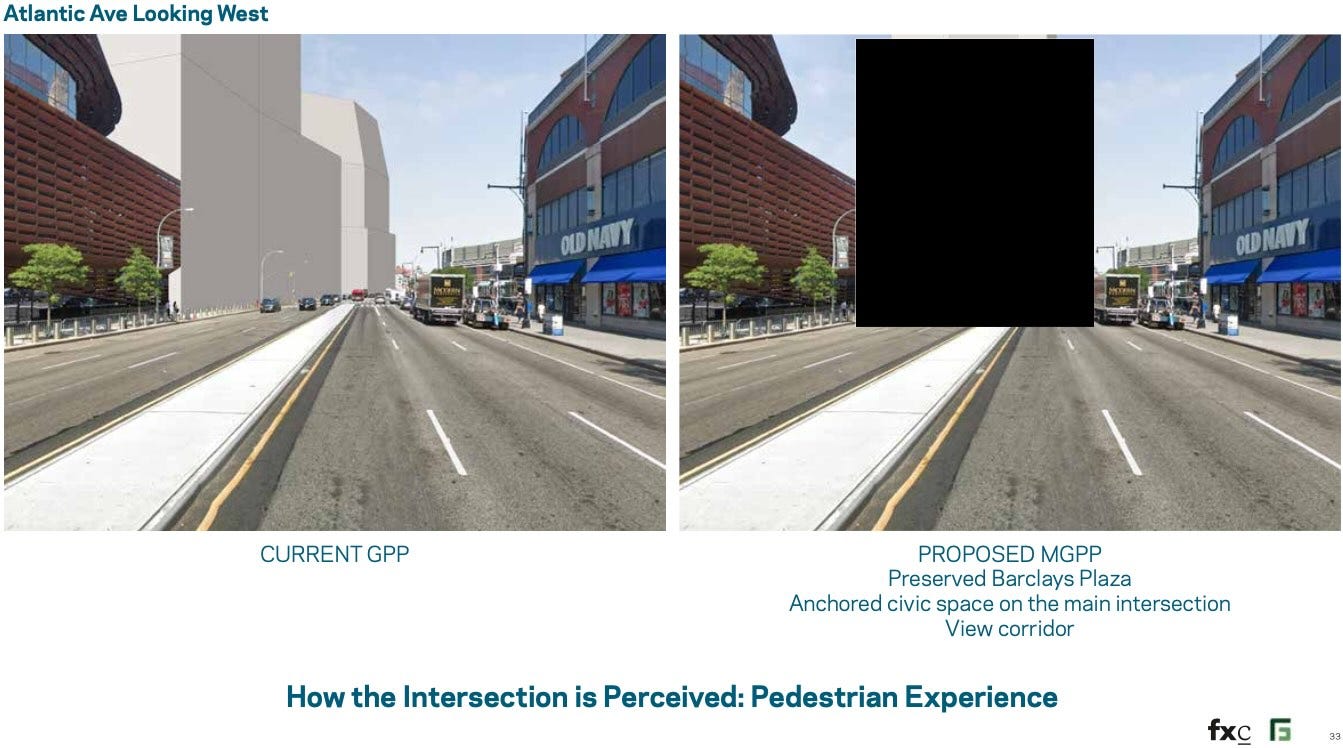

Consider the image below left, which suggests that the current General Project Plan would deliver a blank-walled building, stretching to the curbs of Flatbush and Atlantic Avenues.

Yes, that’s somewhat similar to Keel’s outline, but the pedestrian experience would surely be more inviting than what’s portrayed.

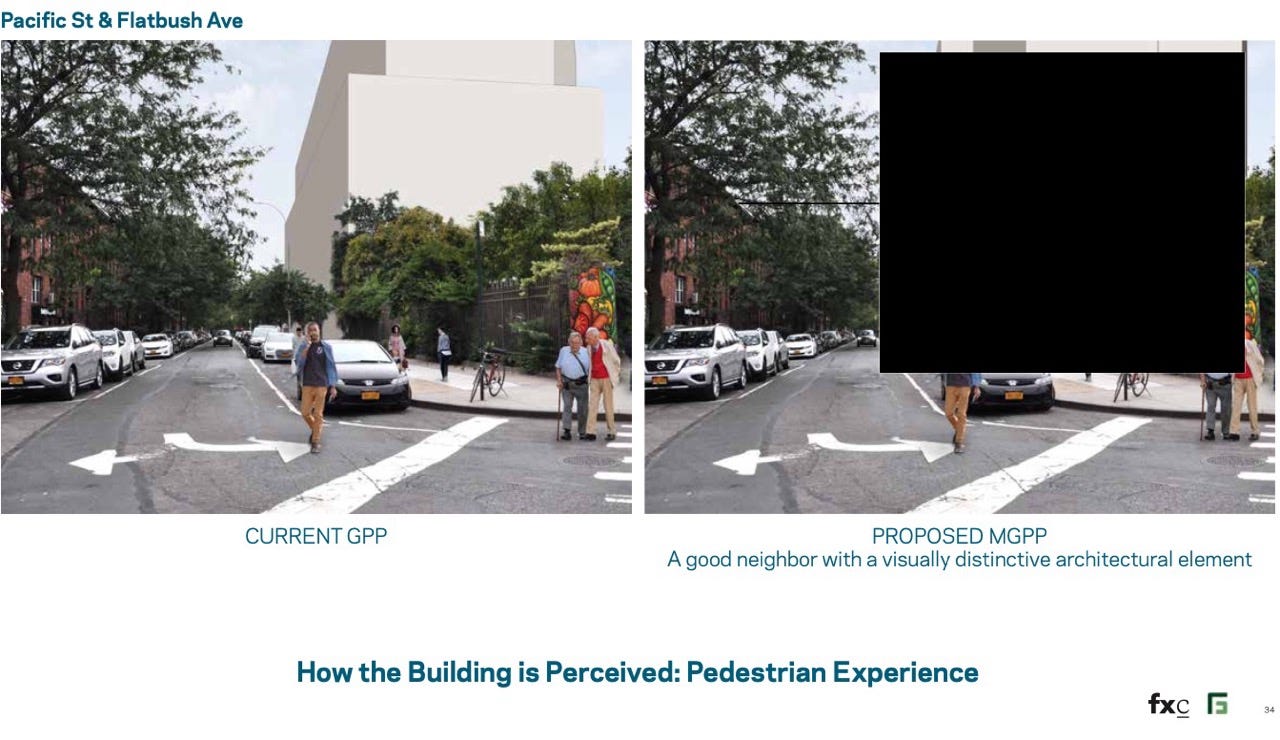

(Also, it implicitly eliminates the Pacific Bear’s Garden, a community garden at the intersection of Pacific Street and Flatbush Avenue, which should persist—or, at least, be re-created— no matter what gets built.)

Whether you like it or not, Gehry’s version of the Urban Room, a glass-walled atrium, and the B1 tower, has fenestration and a mix of shapes and materials.

The FX presentation serves the private interest and likely elements would be transferred to the state’s official public review.

That bolsters the case made in 2018 by Jaime Stein, then a board member of the advisory Atlantic Yards Community Development Corporation, that third-party planning, design and construction consultants review any Site 5 plan.

What about retail?

ESD did not share the details of how a "retail atrium,” referenced two images above, would connect existing public plazas, anchor the intersection, and, presumably, deliver anticipated profit.

Perhaps that’s because most of the retail would be delivered below-grade, replacing parking, and Greenland got New York State’s support for that space to not be counted as additional square feet. In other words, it’s a bonus.

Looking at the proposal

Let’s go through some more of the slides.

Emphasizing the crazy

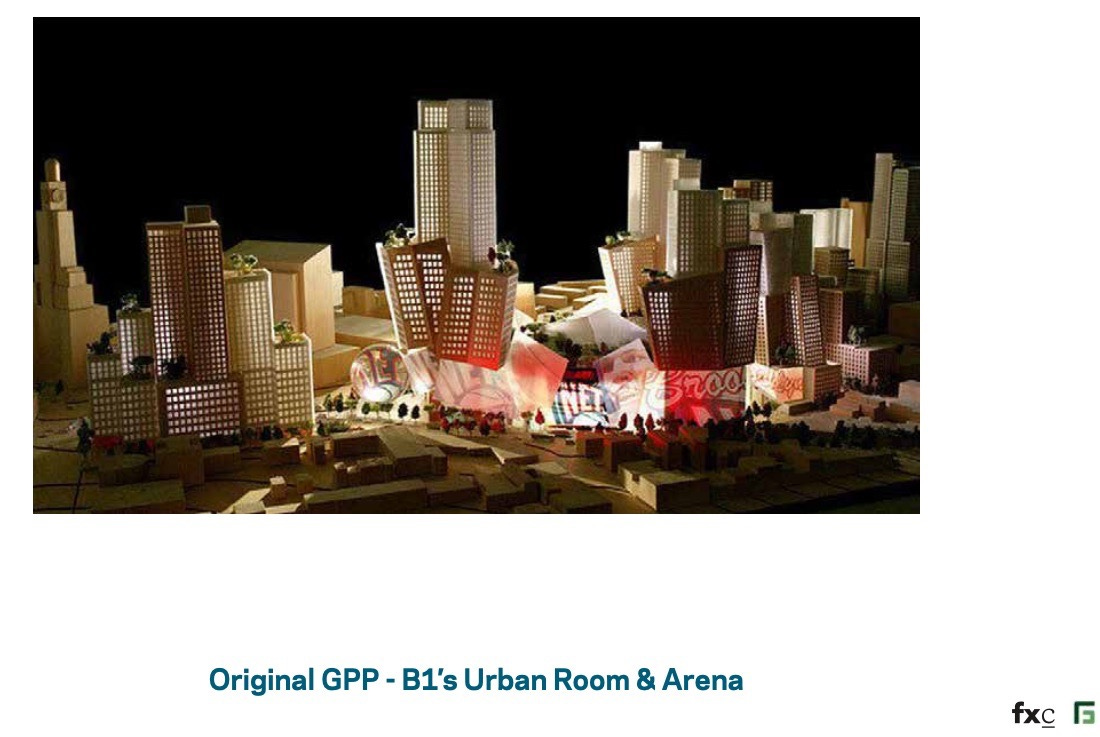

Consider the slide below, showing the Urban Room and Arena from the “Original GPP.”

Well, it’s the arena block, but it’s only one of many Gehry images. The one above is from 2005, while an image a year later was more muted, and those from the 2003 launch were quite different, as were those from a 2008 revision.

Public space?

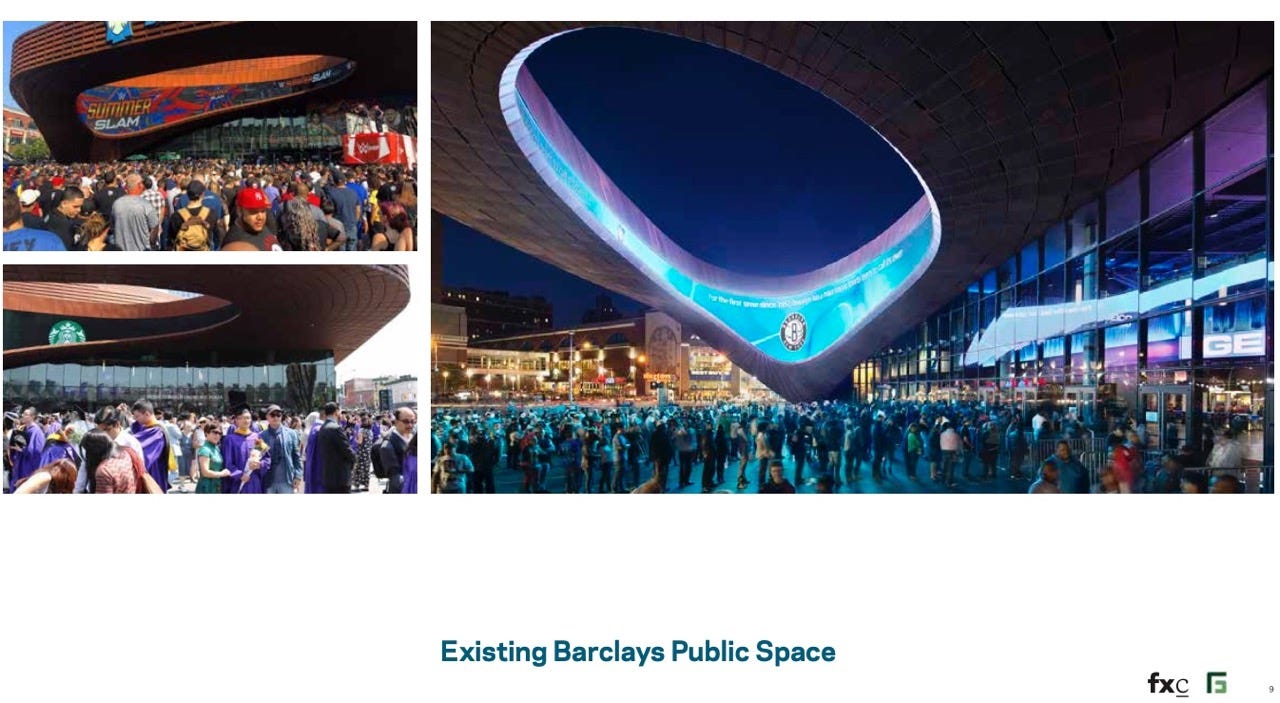

Consider the below image, apparently touting the existing “public space” outside the arena. As far as I can tell, each image depicts the space supporting arena activities, rather than true public use.

The larger image, at right, shows, people entering the arena. The image top left appears to be crowds massing for a wrestling show. The image bottom left, on the day of a graduation held at the arena, depicts graduates posing for photos.

A few years after this 2018 presentation, of course, both the developer and state seized on the plaza’s emergence as what I called an “accidental new town square,” given protests, notably those after the police murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis.

However, that space’s public nature was enabled significantly because the arena was shuttered for the pandemic. Yes, protests have recurred, but they take a back seat to arena events.

Dire impacts of B1

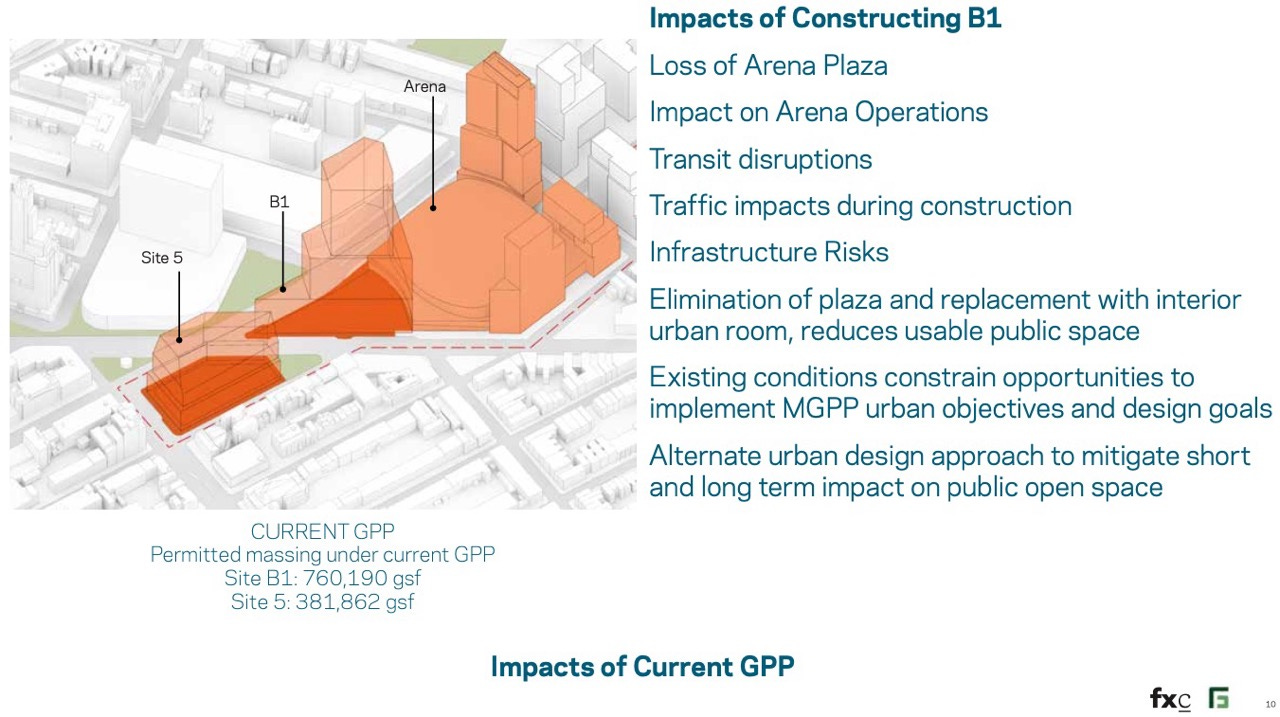

The slide below helps explain why the arena operator and the state would not want Greenland to build B1. (Nor would the developer, for reasons explained below.)

The arena plaza would be lost—replaced, in part, by the Urban Room—but surely more importantly, construction would constrain arena operations, disrupt transit, interfere with traffic, and post risks to infrastructure.

Okay. But why, when Empire State Development allowed original developer Forest City Ratner to not build B1, did it persist with the fiction that the tower could be built, estimating a construction schedule in various technical analyses?

If Building 1 was untenable, they should have told us, and explained whether the developer was sacrificing the square footage or aiming to move it somewhere else.

Why should the public save the developer, Forest City’s successor, from the consequence of its business decision not to build B1? Also keep in mind that tax revenue from that office tower was crucial to projections of public benefit.

Greenland’s case

Let’s fast-forward to an Aug. 24, 2022 letter I acquired, sent to ESD President Hope Knight from Greenland USA President Gang Hu, who said the proposed modifications “would enable the preservation of the Plaza in front of the Barclays Center and improve the overall project to better serve the needs of the community.”

Also, of course, it would better serve Greenland, allowing it to unlock buildable square footage worth perhaps $300 million. It also would serve Joe Tsai, owner of the Brooklyn Nets and the arena operating company, who has sold naming rights to the plaza and otherwise increased the advertising canvas.

Building on the 2018 arguments, Hu’s letter called the plaza “a critical public space” for arena patrons, a backdrop for graduation photos, and a “daily entrance point” for transit riders, as well as place for public protests.

Unmentioned: its commercial value. Also, as shown in the photo above, it’s also cordoned off for arena functions.

The impact of construction

The Urban Room, Hu wrote, “would be interrupted by significant structural core elements that render it unusable by the community as a major and visible gathering site.”

Sure, because it also was supposed to serve the office tower!

During construction of B1, he wrote, “the public would lose access to the transit hub entrance” (really?) and “the arena's operations would be severely altered, with patrons being redirected to secondary entrances along Dean and Pacific Streets.” (I think he meant Atlantic Avenue, plus, maybe, a new entrance at Sixth Avenue and Pacific Street.)

That would be a huge burden on the arena. So keeping the plaza represents a huge bonus.

“Given the complexities of constructing at this location, we anticipate that construction of the B-1 building and Urban Room would take approximately 7-8 years,” Hu wrote.

That’s a long time. Does that mean New York State’s expert consultant’s estimate of 35 months—less than three years— was wrong? (Again, that’s an argument for third-party experts.)

“While the Urban Room was originally a significant component of the Arena Block, our discussions with community stakeholders, local residents and Barclays Center management,” Hu wrote, “makes it clear that the Plaza and transit hub entrance are staples of the community and now provide a primary place where Brooklyn gathers for public and private events.”

Again, that’s an argument for making Tsai pay. The arena needs the plaza. Probably building B1 would be worse for that constricted spot, but the beneficiaries shouldn’t get a pass.

Drilling down

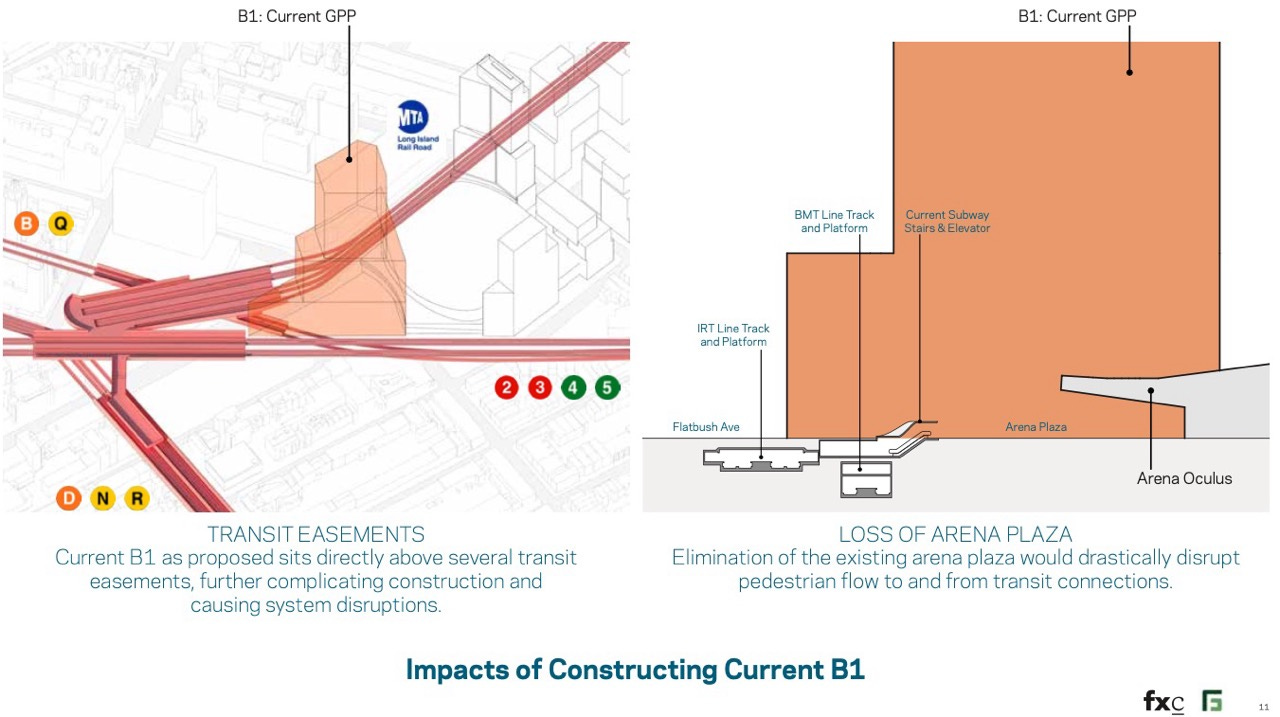

As the 2018 slide below shows, B1 would be built above several transit easements, “further complicating construction and causing system disruptions.” OK, but, wasn’t B1 approved with recognition of those transit easements?

Would elimination of the existing arena plaza drastically disrupt pedestrian flow to and from transit connections? Well it likely would disrupt it somewhat.

But that was the original Atlantic Yards plan approved in 2006 and again in 2009. Are they saying they did a bad job of analysis? (If so, why should we trust any analysis?)

The biggest disruption would be faced by the arena, as it would lose a place for attendees to gather. In fact, had B1 been built, arena crowds might have been forced to gather in the street.

Reducing public space?

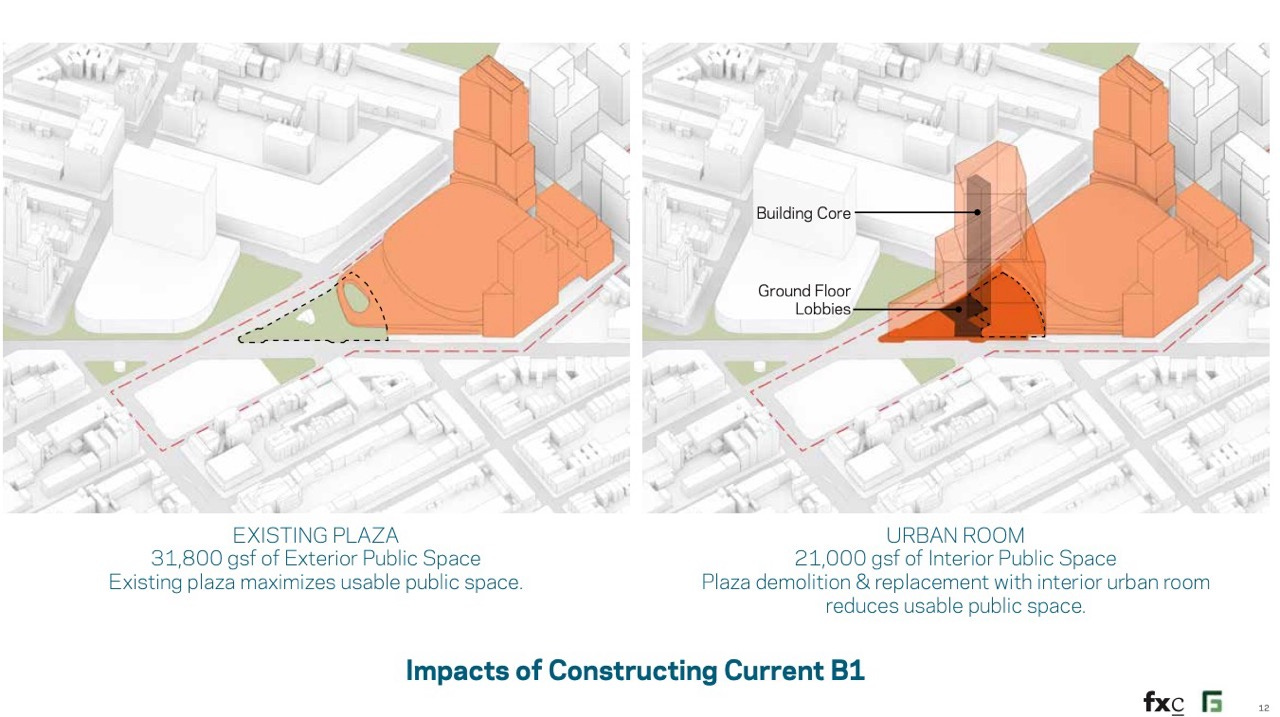

Construction of B1, the slide below suggests, would diminish about a third of the existing public space.

Yes, it would be sharing space with a building entrance, among other things.

Again, that’s what was approved. If the arena company wants the public space, they should pay for it.

If the developer wants to move the bulk, that deserves third-party analysis of the proposed two-tower project.

Additional public space?

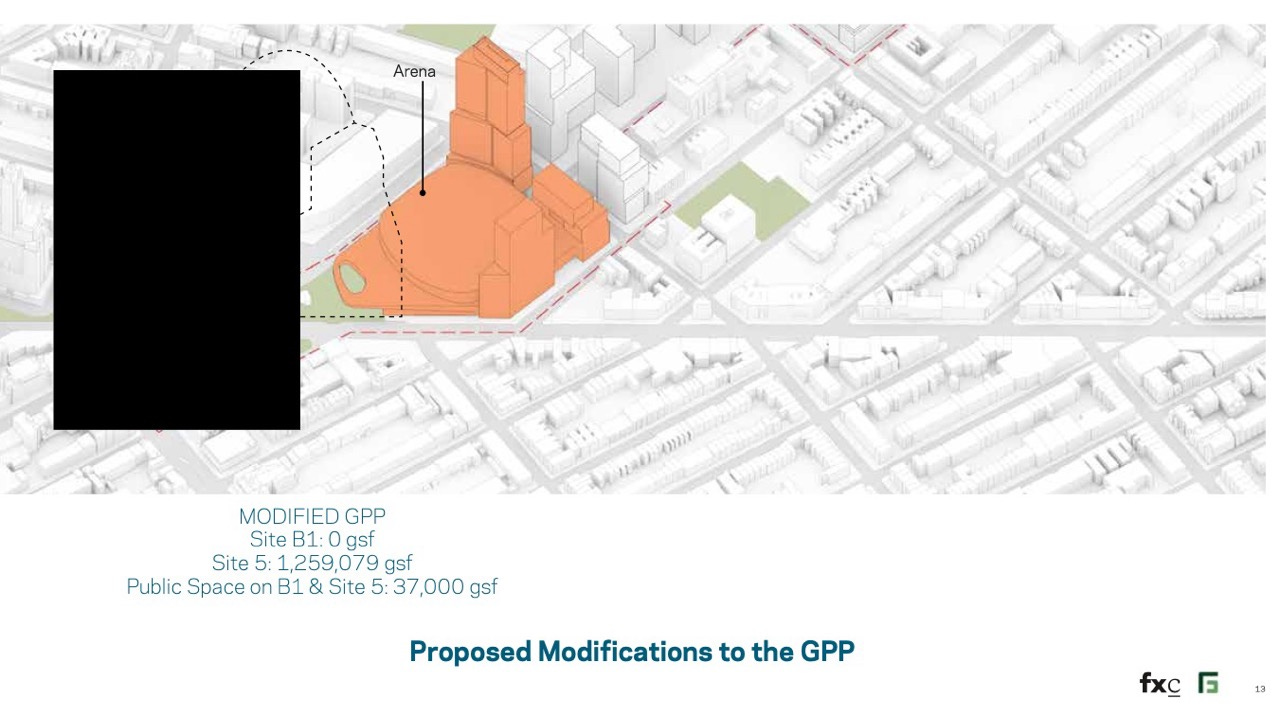

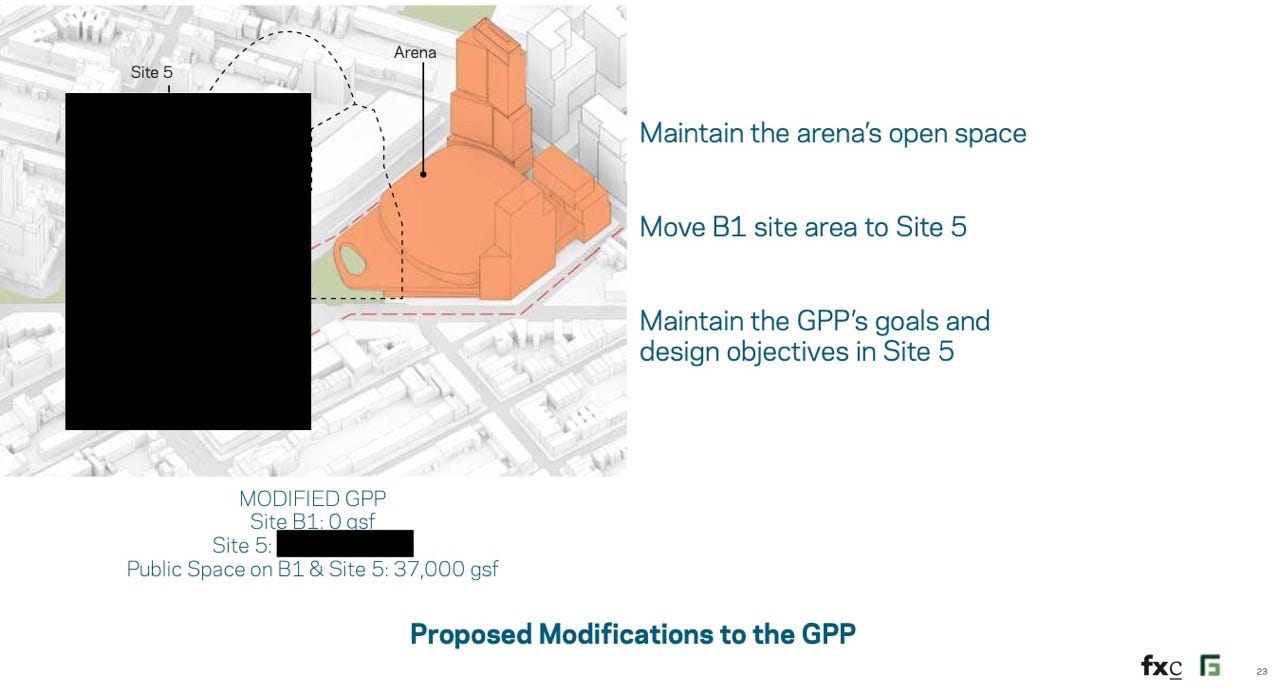

The image below is redacted, but it does indicate 37,000 square feet of public space on the plaza and Site 5, indicating 5,200 new square feet at the latter location.

What’s 5,200 square feet? Well, it’s slightly larger than a standard basketball court (4,700 square feet), or the equivalent of such a court with a tiny buffer zone. Would it be at ground level? Up a few floors? Between buildings? We don’t know.

What’s Site 5’s bulk?

Note that, on the slide above, Site 5 is described as 1,259,079 square feet. That’s significantly more than that proposed in 2016, and a bit more than the 1,242,000 square feet later memorialized in 2021’s Exhibit K.

Though the image and information on the slide below is similar, the bulk of Site 5 is redacted.

That’s curious and inconsistent. Moreover, we already know the similar figure that ESD in 2021 agreed to support.

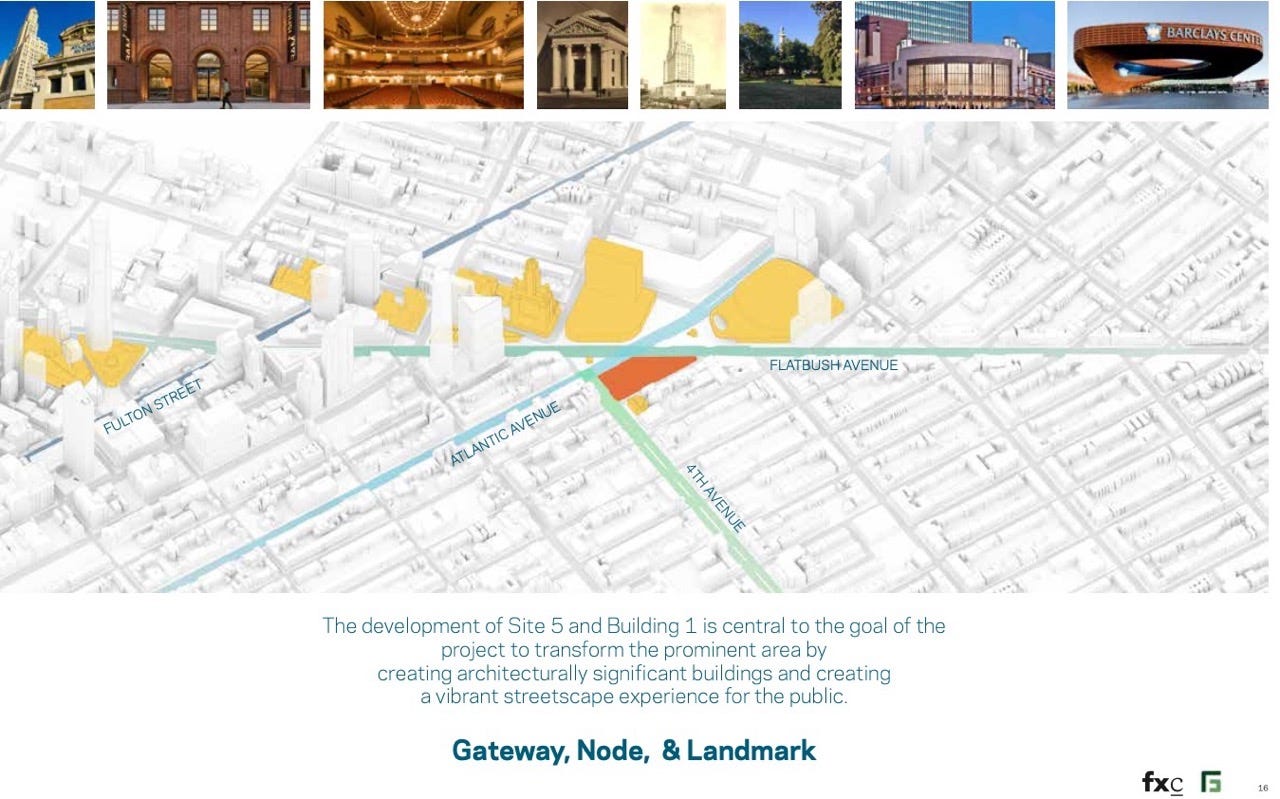

Making a new skyline

The slide states that “the development of Site 5 and Building 1 is central to the goal of the project” to create “architecturally significant buildings.”

That seems a lapse, since the presentation aims to justify the elimination of B1 and create one significant building.

The argument for a new skyline, of course, has been made for each proposed change in Site 5.

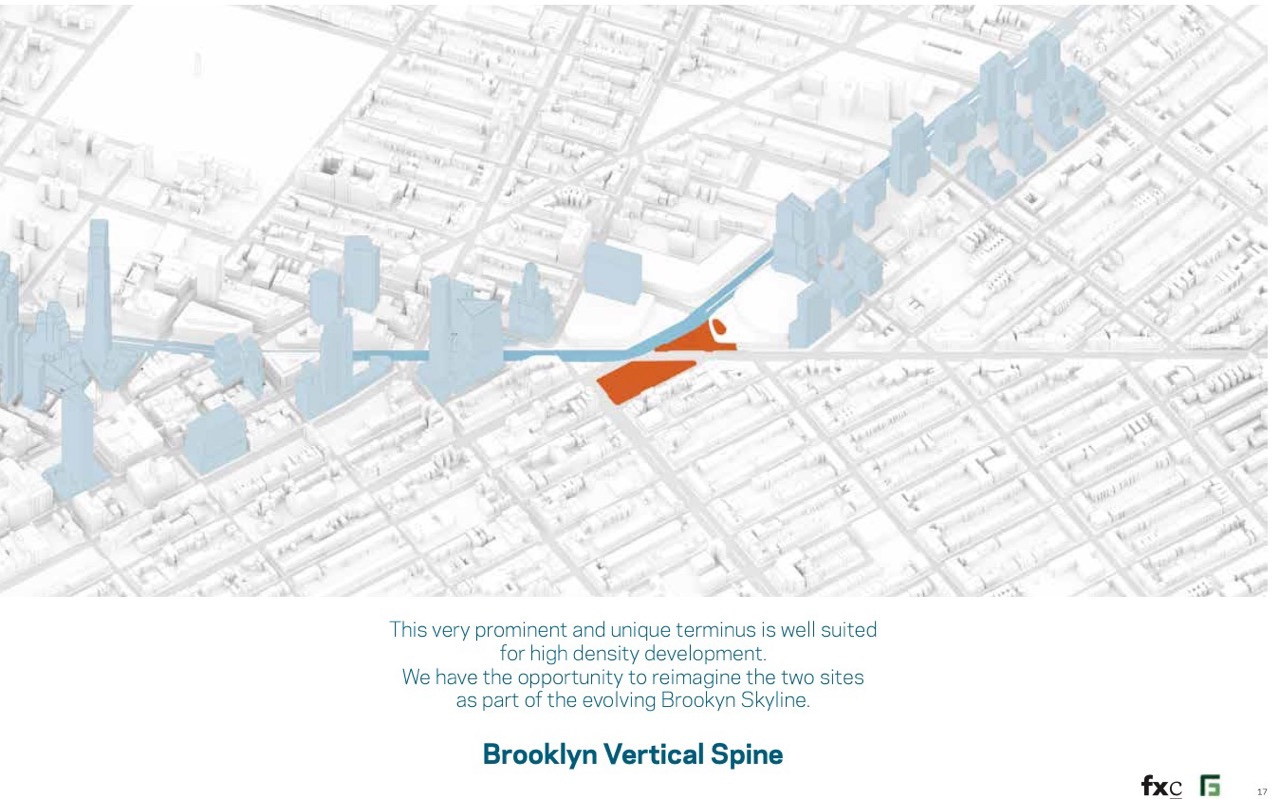

Key crossroads

“This very prominent and unique terminus is well suited for high-density development,” the slide says.

OK, but the City Planning Commission in 2006 successfully recommended that Site 5 be cut from 350 feet to 250 feet made smaller, given that it transitions to a lower-rise area.

Yes, the context has changed, with buildings 14 to 16 stories along Fourth Avenue, as well as much larger buildings along Flatbush Avenue. But Site 5 still borders low-rise Pacific Street and a low-rise section of Atlantic Avenue.

So it deserves reassessment, rather than simply endorsement of terms like “Brooklyn Vertical Spine,” which, as with “The Brooklyn Trio,” may be arbitrary. (Note my 2018 prediction that 80 Flatbush might be a precursor for an updated Site 5 argument.)

New open spaces

The slide below apparently makes the case for a “harmonious network of open spaces” including Site 5 and the arena.

They just won’t show it to us.

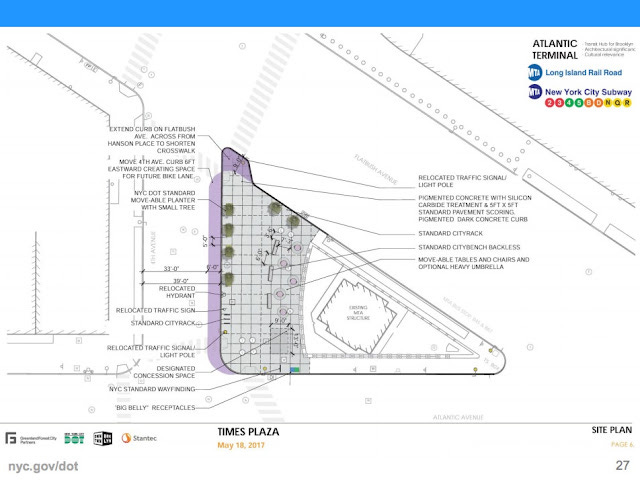

Which reminds me: Times Plaza, just above Site 5, was supposed to be revamped as open space, but that never happened. In October 2017, I reported that the developer said open space work—on about 4,500 square feet controlled by the Department of Transportation—might go into construction in the second quarter of 2018.

That didn’t happen. “The developer remains in ongoing discussions with the Department of Transportation,” then-ESD Atlantic Yards Project Director Tobi Jaiyesimi said at a public meeting in January 2022.

Greenland’s essential withdrawal from the project surely hasn’t helped.

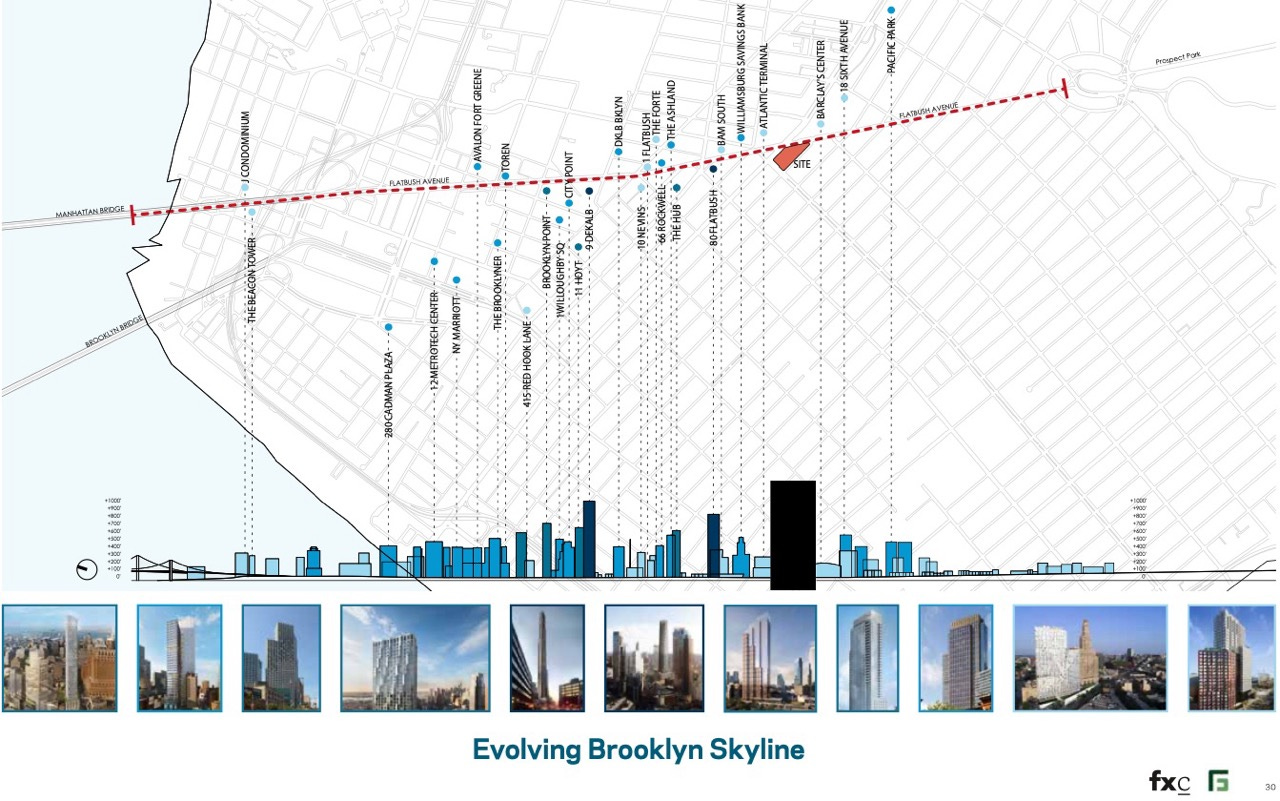

Evolving skyline

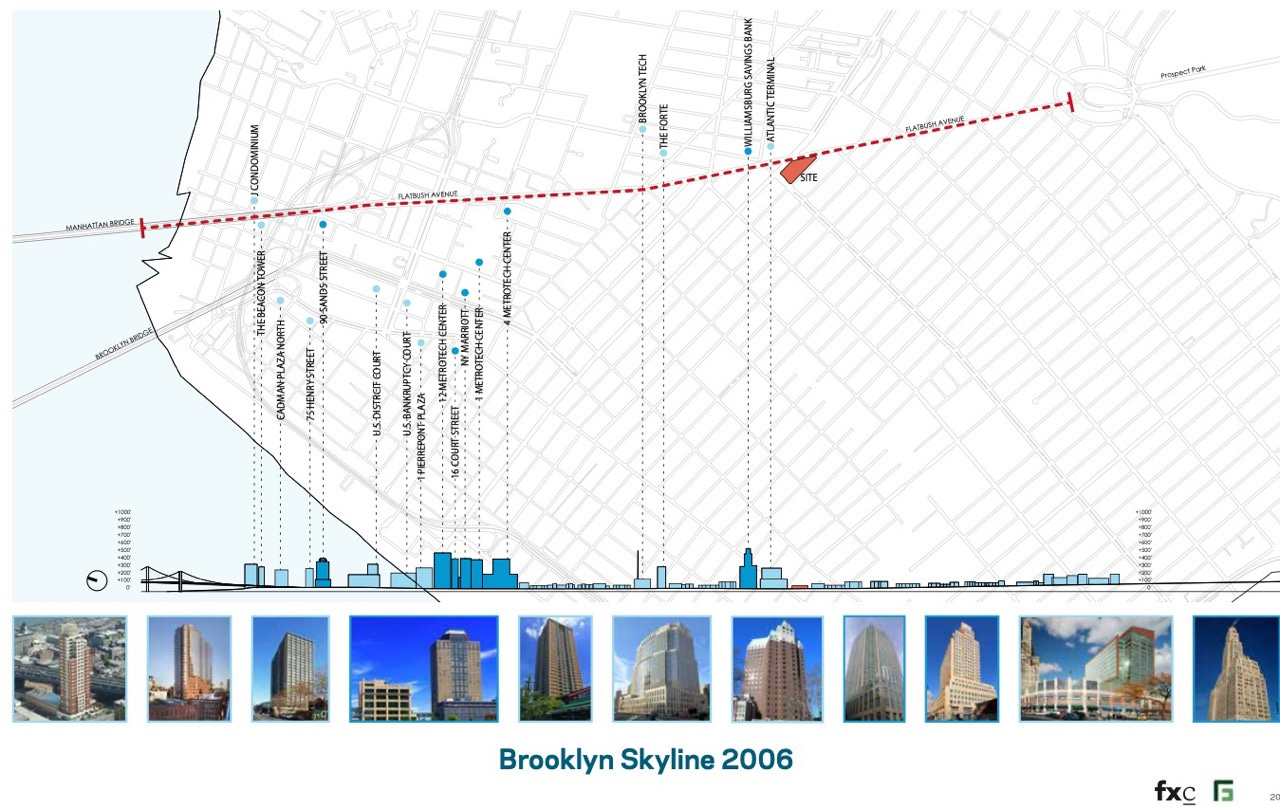

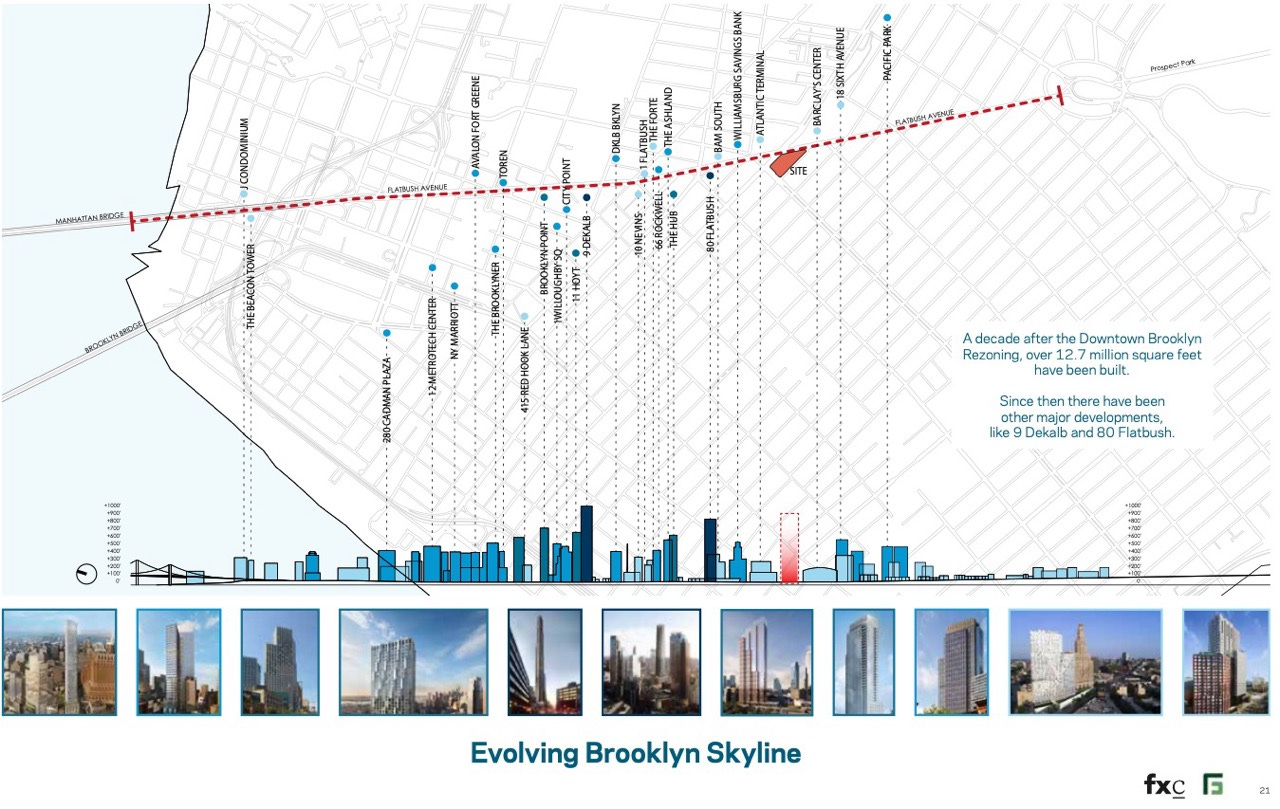

Yes, the context has been changing, with more towers making their way toward the Atlantic/Flatbush intersection. The below slide, showing the emerging skyline as of 2006, is history.

Note that, while Site 5 had been approved, the outline does not appear on the rendering above.

In the rendering below, the outline of the proposed Site 5, apparently, is shown in a fuzzy red outline. Perhaps the upper vertical line—above 900 feet, in my judgment—indicates the height of the larger of the two towers, while the northern border of the color indicates the height of the shorter tower.

In the image below, however, even that fuzzy outline is redacted.

Again, that’s inconsistent, and suggests it’s not exactly a trade

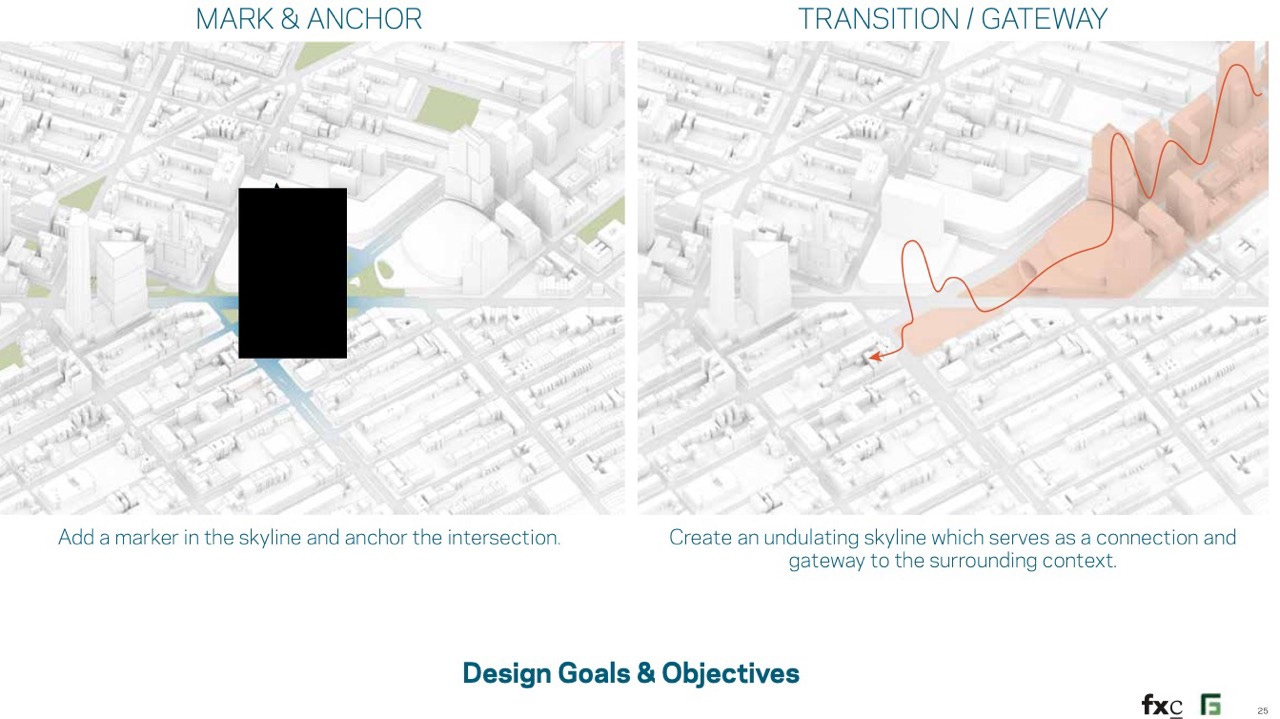

An undulating skyline?

The building, the left slide suggests, would “add a marker in the skyline.” Well, what makes an anchor? How big? What’s the difference between the previously proposed undulation and the one more recently proposed?

As to creating an “undulating skyline,” that’s hard to assess, since the undulation is portrayed in another helicopter view.

More on the streetscape

As with the image noted above, the outlines of the approved streetscape at B1 and Site 5, looking west from Atlantic Avenue near Sixth Avenue and looking west from Pacific Street near Fifth Avenue, portray the possibilities in the least flattering light.

These images would hardly be a commercial choice. Meanwhile, the proposal is redacted.

Design principles

Sure, the principles below—such as a variety of materials, and a sculptured setback—are fine. However, they could apply to a lot of options.

Not until we see the options can we accurately assess them. The design principles are fine, but they could apply to a variety of proposals at this location.

Why are developers in love with these doomy-looking supertall buildings?