Do Joe Tsai and Clara Wu Tsai Own the Barclays Center? No.

The common, erroneous shorthand, lately in the New York Times, obscures the governmental largesse that has helped fuel huge financial gains.

I wasn’t going to send a newsletter this weekend, since I’m working on my end-of-year roundup, but I couldn’t let this pass.

So New York Times columnist Ginia Bellafante, in her weekly Big City column, today offers the cheerful 7 People (and One Coyote) Who Made New York City a Better Place in 2024, citing “bright lights during a rocky year, making the city a cooler, and fairer, place to be.”

Not so fast.

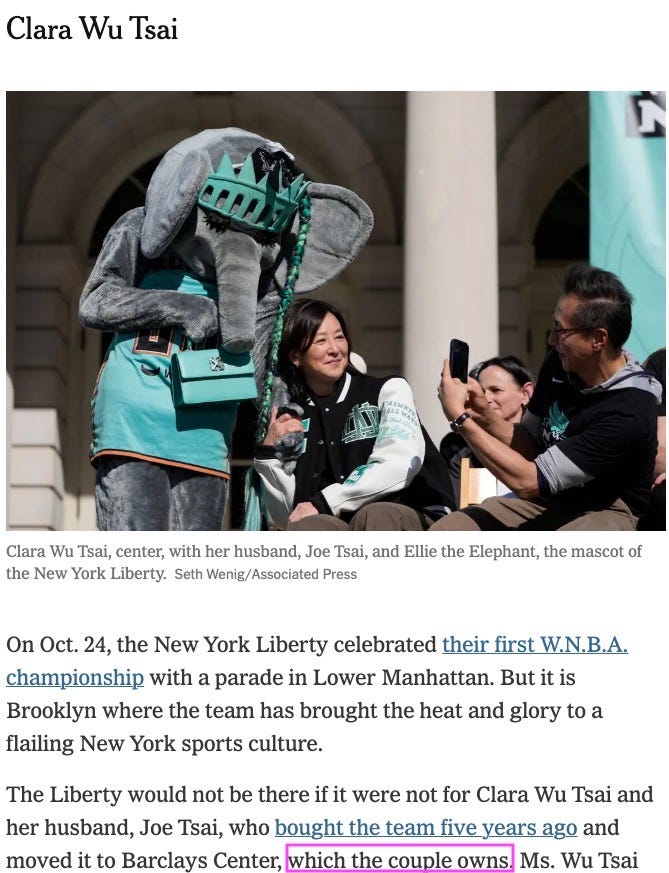

Consider the passage highlighted below regarding Clara Wu Tsai, who with her husband Joe Tsai savvily invested in the WNBA’s New York Liberty enough to win a championship, complete with a memorable mascot, Ellie the Elephant.

Bellafante saluted the Tsais, noting they “bought the team five years ago and moved it to Barclays Center, which the couple owns.”

Except they don’t own the arena, but rather the operating company.

That erroneous shorthand obscures efforts to make the city “fairer,” since nominal state ownership of the arena, leased to the Tsais, enables enormous savings on tax-exempt land and tax-exempt construction bonds.

Looking more closely

If you ask Google if Joe Tsai owns the Barclays Center, the AI Overview—garbage in, garbage out—says yes, relying on a press release from the Barclays Center headlined “Joe Tsai Completes Acquisition of Full Ownership of Brooklyn Nets and Barclays Center, excerpted below, and another from NBA.com.

It’s a common shorthand, deployed by the New York Post, CNBC, and other media outlets, following the moguls’ cue.

However, if you ask Google who owns the Barclays Center, it delivers a more accurate link to Wikipedia:

The arena is owned by the State of New York's Empire State Development authority through a public entity named the Brooklyn Arena Local Development Corporation. It is leased by Brooklyn Event [sic; it should be Events] Center LLC, owned by Brooklyn Nets owner Joseph Tsai, with operations (and associated revenue) managed by Tsai's BSE Global.

Wikipedia, thankfully, links to an April 2018 essay I wrote for City & State, No, Mikhail Prokhorov doesn't 'own' the Barclays Center, subtitled “Nominal ownership by New York state enables tax breaks.”

Forbes, to its credit, got it right, in August 2019 reporting:

Tsai is not just taking control of the basketball franchise; he’s also agreed to buy the operating rights to the Barclays Center, where the Nets play, in a separate transaction (the state owns the building itself).

In the Times?

What about the New York Times clip file? Well, Bellafante’s article links to a Times article on the Liberty acquisition, which doesn’t address ownership of the arena.

Go back a little farther, to August 2019. Covering Tsai’s full purchase of the Nets, the Times alluded to the team owner’s right to operate the arena, not own it:

The deal does not include a stake in the Barclays Center, the team’s arena, though Mr. Tsai is expected to eventually gain control of that, too. Mr. Prokhorov’s Onexim Sports and Entertainment currently controls the arena’s operating rights.

A deeper dive into the Times clip file might surface a June 2010 essay (by me), A Russian Billionaire, the Nets and Sweetheart Deals, which cites the “fig leaf of public ownership” for the arena, enabling tax-exempt bonds.

A complex structure

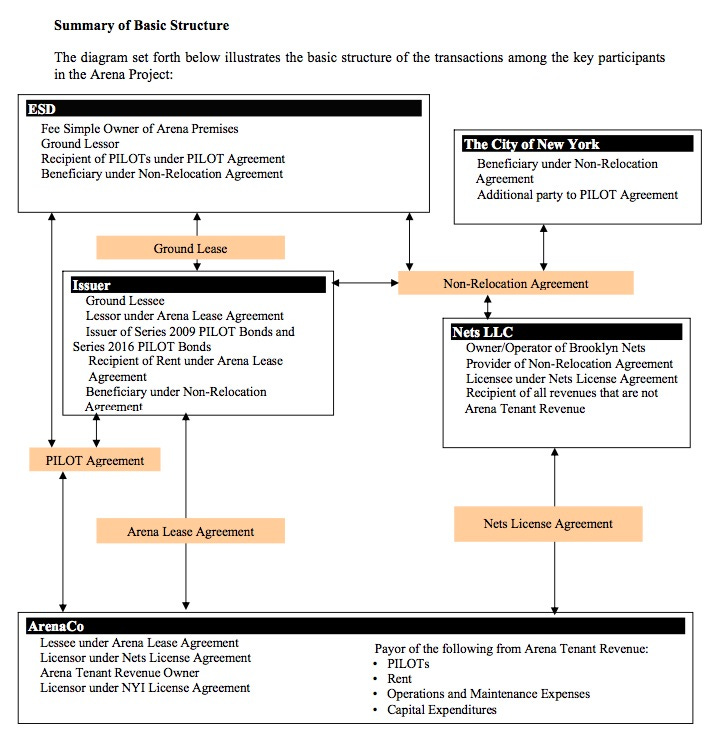

The complex ownership structure is memorialized in various documents. Here’s the ground lease from Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC, now known as Empire State Development, or ESD) to its affiliate Brooklyn Arena Local Development Corporation (BALDC).

Here’s the Memorandum of Agreement of Arena Lease between the state-owned BALDC and Brooklyn Events Center, then an affiliate of original arena developer Forest City Ratner and now owned by the Tsais’ BSE Global.

Below is a more generic structure, from the 2016 arena bond prospectus.

As I wrote for City & State:

BALDC, called the “Issuer” in this [above] chart (from a 2016 bond document), has an arena lease agreement with ArenaCo (aka Brooklyn Events Center), a subsidiary of another company, which is [in 2018] owned by Prokhorov.

Why the Rube Goldberg structure? It unlocks two benefits typically unavailable to owners of private property: avoidance of property taxes, and access to tax-exempt financing.

Yes, the arena operator must pay for arena construction. But it’s a sweet deal.

Instead of paying taxes on the site, the arena operator instead makes payments in lieu of taxes (PILOTs) to pay bondholders for construction costs. Watchdog state Assemblymember Richard Brodsky once likened it to sending "my tax payments to the bank to pay off the mortgage."

We shouldn’t let a championship and some well-promoted charitable ventures obscure that reality—or that of unconscionable deals at other New York City sports venues. (Hello, Madison Square Garden.)

Big profit

In 2024, foregone taxes on the Barclays Center site topped $110 million. The arena company instead made $39.3 million in PILOT payments in FY 2024; however, operators got back $11.6 million to use for operations and maintenance.

The arena’s not very profitable yet, though it’s making progress. However, the bigger picture suggests a huge win.

Control of a team and an arena in the world’s media capital allowed the Tsais this year to garner a 15% investment in BSE Global, at a skyrocketing valuation of $5.8 billion (or $6 billion) from, yes, the family of the late right-wing billionaire David Koch. BSE Global, without the Liberty, had cost the Tsais at most $3.3 billion.

That’s a huge $688 million payday for the Tsais, and the most dramatic leap in value for any NBA team company, according to Sportico. (The Times coverage, via its sports vertical The Athletic, simply described the Tsais’ BSE Global as “parent company of the Brooklyn Nets, New York Liberty and the Barclays Center.”)

Public promises unmet

Remember, the Barclays Center is part of a megaproject announced as Atlantic Yards (and renamed in 2014 as Pacific Park Brooklyn, though many used the original name) that is not even half-complete, with eight towers (of 15 or 16) built and an expensive, complex platform needed over an exposed railyard.

While original project developer (and Nets owner) Bruce Ratner was once expected to get rich, that didn’t happen. Instead, the big winners have been the owners of the Nets and the ArenaCo, Prokhorov and the Tsais, surfing the rising value of NBA teams.

As I wrote, the highly touted public benefits of Atlantic Yards—affordable housing, open space, jobs (both construction and office), removal of blight, new tax revenues—have been delayed and diminished, though such projections were used to justify public support.

Benefit to ArenaCo

Yeah, it’s complicated, but we should get the ownership issue right.

After that, we might realize, as I’ve written, that New York State seems ready to give the Tsais another bonus: permanent control of the arena plaza, once slated to be the site of a giant office building (aka B1) fronted by a public atrium (aka “Urban Room”) to be used by both arenagoers and office tenants, among others.

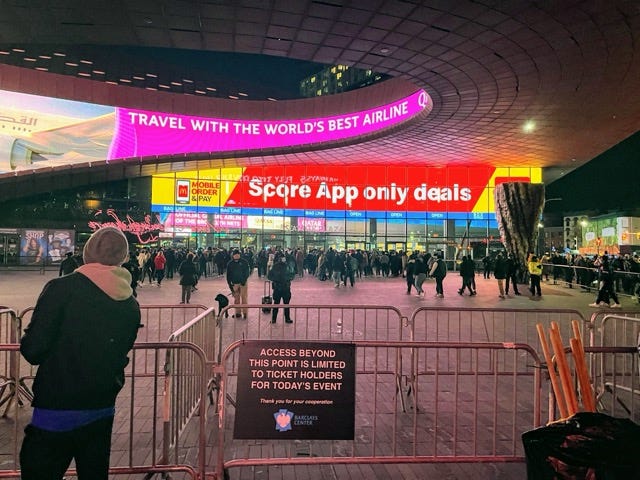

Would Joe Tsai's Slickest Move Be Poaching Ticketmaster Plaza?, I wrote in July, citing the current sponsor. That “temporary” parcel is crucial to enhancing the guest experience and allowing space for promotions and advertising.

New York State officials are expected to soon justify transferring the bulk of the unbuilt B1—which original architect Frank Gehry dubbed “Miss Brooklyn”—across Flatbush Avenue to what’s known as Site 5, to enable far larger towers than approved. One justification: the civic value of preserving the plaza.

Yes, the plaza serves a crossroads, transit entrance, and even sometime protest location, as it was “totally appropriated” in 2020, according to one organizer. But that’s trumped by commercial value.

For example, the plaza’s cordoned off to manage arena access during events, and used as a canvas for various promotions, not just in the wraparound oval oculus but in the LED “wall” over the arena doors, as the photo above shows.

Moreover, not building the promised B1 tower, which was supposed to contain office jobs crucial to Atlantic Yards’ expected tax revenues, helps the Tsais avoid a huge headache: construction interfering with arena access.

The bottom line

Maybe winning a WNBA championship, fueling a parade and a viral mascot, made New York City a better place, albeit briefly. Increased New York Liberty fandom—at newly inflated ticket prices—may continue the trend.

“There is nothing like professional sports to make public people nutty," the late watchdog Brodsky once said in Congressional testimony, referring to the willingness of various government entities to subsidize what subsidy skeptic Bettina Damiana called privately owned "sports entertainment corporations."

Yes, sports brings people together and helps build community identity. But that also makes "public people," like the elected officials cheering the Liberty, forget things. Columnists, too.

I’ve been reading all your reports. So very informative since our failed protests so long ago to stop this arena project.

It’s a great shame the NYTimes edit room can’t get these simple facts straight.