Developer Certified that EB-5 Spending was Compliant, but Evidence Shows Otherwise

New York State limited use of investor visa funds, targeting railyard tower sites. But the money was reported as supporting two other towers.

Was the $249 million in EB-5 funds—$500,000 each from 498 immigrant investors—raised in 2014 for Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park spent appropriately?

Clearly, no. Evidence, some long publicly available, shows the developers and the U.S. Immigration Fund (USIF)—the EB-5 middleman, or regional center—ignored New York State requirements regarding the money.

According to state strictures, the only towers that funding could support were the six over the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s (MTA) Vanderbilt Yard, parcels B5-B10, plus the B15 site.

However, much of the “Atlantic Yards II” money was spent, documents show, on two ineligible towers, B3 (38 Sixth Ave.) and B11 (550 Vanderbilt Ave.). Both were already in process and B3, as I explain below, was already largely funded.

New York State had ruled out such spending, apparently aiming to ensure that the new funds would advance the project.

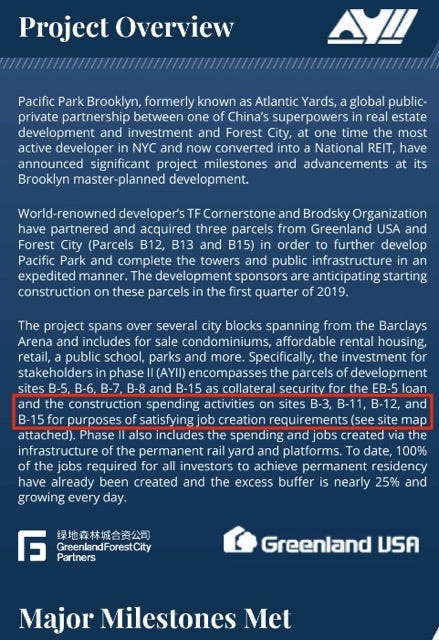

Such sophistry is not surprising, given a history of misleading marketing with EB-5, such as a brochure, excerpted below, suggesting that the investment “project”—a segment of the larger Atlantic Yards project—involved basketball and the already-built Barclays Center.

That said, the portion of the $249 million spent to revamp the MTA railyard, used to store and service Long Island Rail Road trains, did comport with state requirements.

Behind EB-5

Under EB-5, the investors accept low or no interest rates, since they prioritize green cards for themselves and their family. Developers get low-interest loans. The regional centers get the spread, plus fees, some of which are paid to immigration brokers to recruit investors, in this case in China.

The public policy justification? Such investments purportedly create jobs. (As noted below, there’s reason for doubt.)

“This savings to the developer,” NYU Stern School of Business’s Jeanne Calderon said in February 2106 testimony to the House of Representatives, “is the equivalent of a government subsidy that is available because the government is willing to issue an EB-5 visa to the immigrant as the incentive for his investment.”

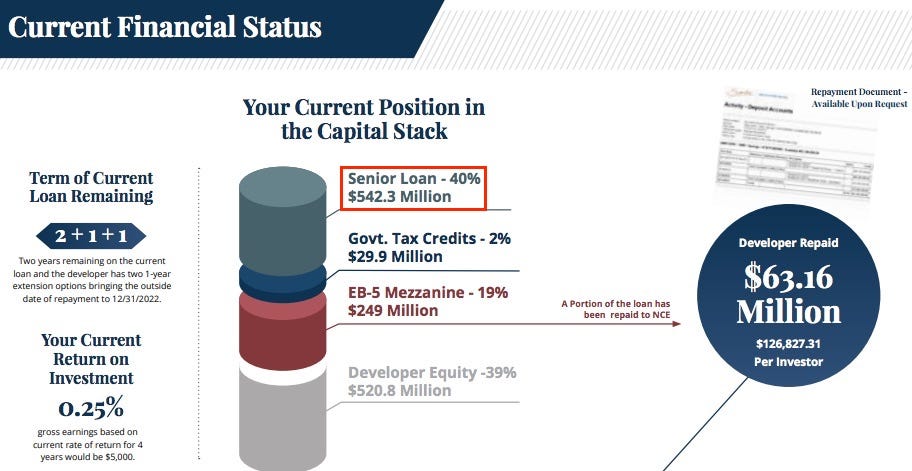

The investors do expect their money back, after five to seven years. In this case that’s in doubt, given the pending foreclosure sale, pursued by a USIF affiliate, of developer Greenland USA’s rights to six tower sites over the railyard.

When the money was borrowed, original developer Forest City Ratner, which had sold 70% of the project going forward to Greenland, was part of the loan. Later, Greenland took over all but 5% of Forest City’s share. Now Brookfield, which later absorbed Forest City, has a “nominal” stake.

Reasons for doubt

The evidence of noncompliance raises questions about how much Empire State Development (ESD), the state authority that oversees/shepherds Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park, should trust the parties it’s working with to find a new developer in the foreclosure sale.

(The sale is scheduled for Feb. 12, but has already been postponed once.)

I shared much of the evidence I’d gathered with ESD. “ESD is currently reviewing documents,” a spokeswoman responded. “We will come back to you when we have concluded our review.” ESD, presumably, could pursue sanctions for an Event of Default.

I didn’t get a response from Greenland USA or the U.S. Immigration Fund.

The federal government, which oversees EB-5, may not care, since it focuses not on state restrictions but on whether the spending reflects the business plan and thus creates, at least according to dubious EB-5 math, the required ten jobs per investor.

Moreover, EB-5 cases involving clear fraud—as in this recent New Yorker article—likely take precedence.

That said, I also found evidence, albeit less conclusive, that suggests that the USIF’s job-creation claim was exaggerated, as explained below.

Reports missing

As I wrote, ESD required annual reports on how the $249 million was spent starting in early 2015, but didn’t get minimal documentation until mid-2019, apparently spurred by my Freedom of Information Law Request.

Nor did ESD have such records, a state official acknowledged at the Jan. 23 meeting of the advisory Atlantic Yards Community Development Corporation (AY CDC). So the AY CDC formally requested its parent body provide such reports.

But evidence shows the spending was not limited to the categories listed in a Sept. 9, 2014 ESD Consent Letter that the lender and the borrower had to sign.

Such evidence contradicts the June 24, 2019 Expenditure Certificate signed by Greenland USA’s Gang Hu that certified, without evidence, that the loan proceeds for “Atlantic Yards II'“ as well as a later $100 million EB-5 loan, “Atlantic Yards III,” paid for costs that ESD considered Permitted Uses.

Glaring evidence

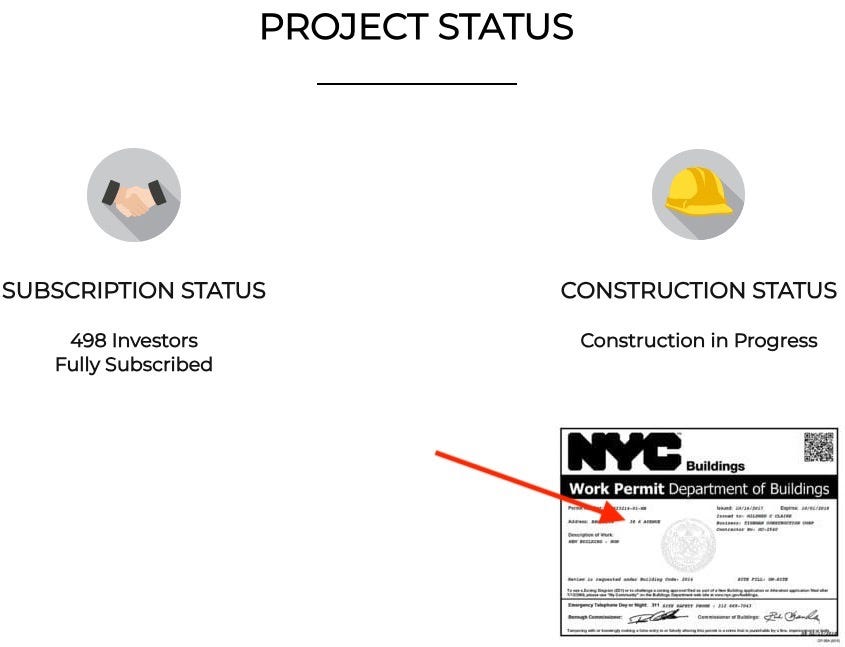

The spending emphasis has long been obvious. The screenshot below, from the U.S. Immigration Fund’s web page for “Atlantic Yards II,” shows a New York City Department of Buildings permit for 38 Sixth, or B3.

The photos and images below, from that same USIF web page, focus on the under-construction B11, B3, and Vanderbilt Yard, plus a rendering of the arena and adjacent towers, and the completed B11.

They even throw in an image of 535 Carlton (B14) and another of the block containing that tower and B11.

The U.S. Immigration Fund was founded by Nicholas Mastroianni II, who in October 2014 was the subject of a critical article by Fortune’s Peter Elkind, The tangled past of the hottest money-raiser in America's visa-for-sale program, which cited his "long history of legal problems, failed ventures, and unpaid debts."

(I thought it would’ve been tougher had it cited the dubious “Atlantic Yards II” marketing.)

More evidence

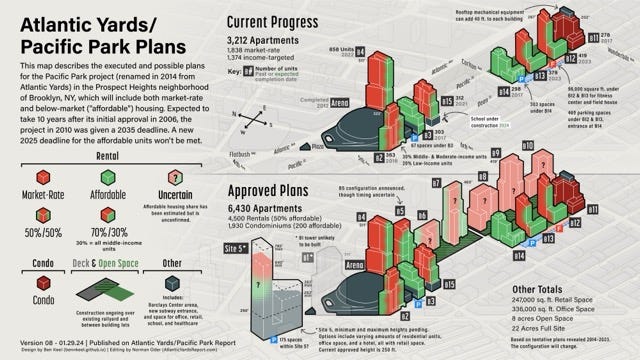

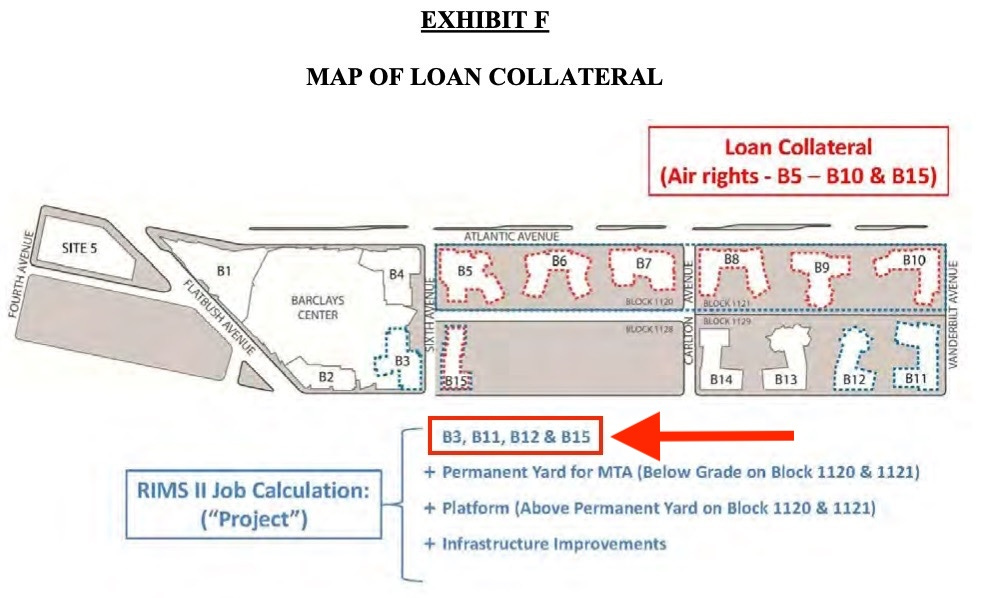

Consider the image below, which I published mainly to point to the seven parcels (B5-B10, plus B15) that served as collateral for the $249 million loan. It offered crucial clues about the spending.

As shown in the text highlighted by the arrow, the project elements used to calculate job-creation included the permanent MTA railyard; the platform over the railyard to support six towers; infrastructure improvements; and construction of the towers B3, B11, B12, & B15.

The image came from a Private Placement Memorandum sent to potential investors, dated Jan. 2, 2014. Nine months later, however, ESD’s Consent Letter constrained such spending.

It did allow the first three categories cited above, plus payment for the MTA air rights. But it only allowed spending on the parcels offered as collateral: the six sites over the railyard, plus B15.

Why? It’s not specified in the Consent Letter, but presumably ESD knew that other buildings under construction—the “100% affordable” B3 (38 Sixth) and B14 (535 Carlton), plus the condo tower B11 (550 Vanderbilt)—had other sources of funding and were already in process.

Reporting back

The evidence mounted. A Q3 2018 Shareholder Report to “Atlantic Yards II” investors from the USIF, maintained the fiction.

(I first wrote about it in March 2019 roundup about skeptical Chinese investors organized by advocate Zoe Ma, who stated, “I’m going to show the world how Chinese investors are duped.” A state lawsuit was not successful, but she, along with frustrated investors, has raised significant questions about this and other EB-5 projects.)

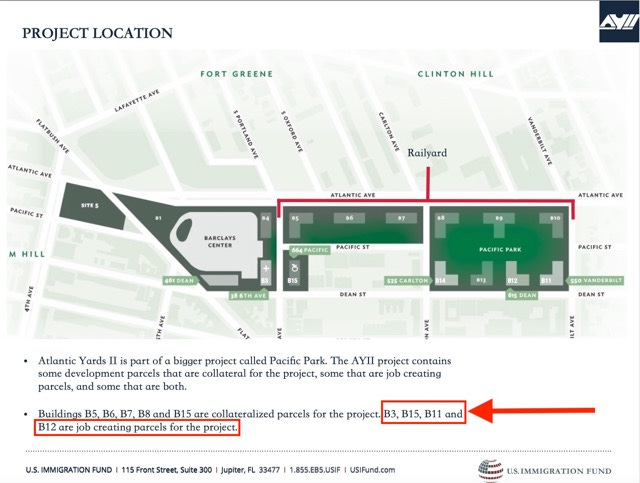

As stated in the screenshot below, the USIF stated that the collateralized parcels for “Atlantic Yards II” were now only B5, B6, B7, B8, and B15. (In 2015, B9 and B10 were severed to provide collateral for the “Atlantic Yards III” EB-5 loan, of $100 million, thus diluting the collateral.)

The page also claimed that B3, B15, B11, and B12 “are job creating parcels for the project.” That, of course, contradicted the Consent Letter.

Multiple pages in the document focused on the progress of B11 (550 Vanderbilt), including citations of press coverage.

Stretching the truth

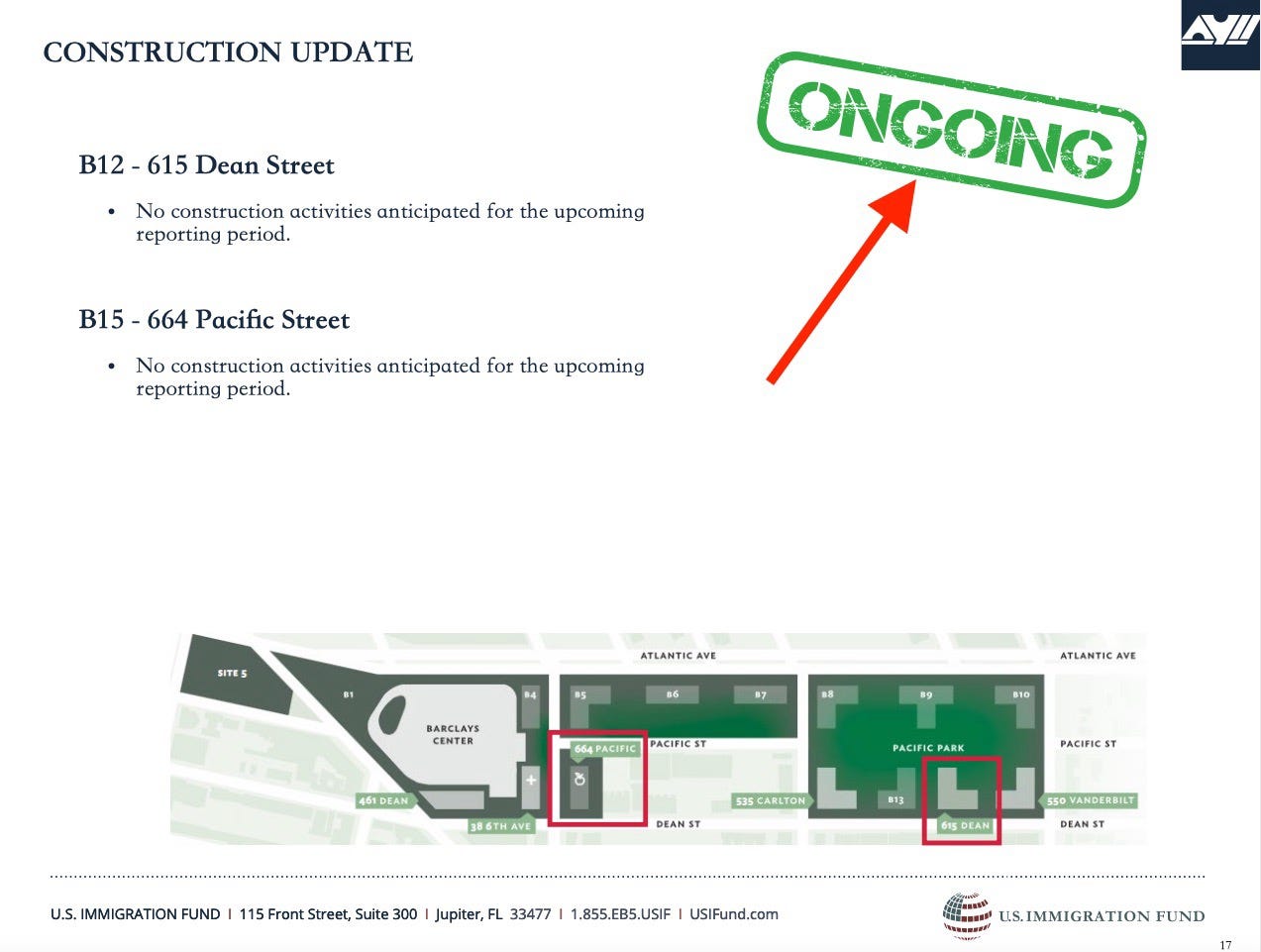

Putting aside the Consent Letter conditions, the claim that B12 and B15 might be job-creating parcels was ridiculous. Neither—despite the production of renderings—had started construction, beyond minor site clearance.

But the shareholder report, aimed at less sophisticated observers, pushed hard.

Consider the slide below, which acknowledges that, for both the B12 and B15 towers “no construction activities anticipated for the upcoming reporting period,” typically two weeks.

Yet the word “ongoing”—as I’ve highlighted with the arrow—misleadingly suggests something was happening.

Note: while that read like an excerpt from a bi-weekly Construction Update circulated by ESD after preparation by the developer, I couldn’t find one in the first nine months of 2018 with that specific text.

The closest was a March 26, 2018 document that stated, re B15, “No construction activities anticipated for the upcoming reporting period” and, re B12, “The 16 foot fence has been removed. Work grading the site will continue.”

Keeping up the charade

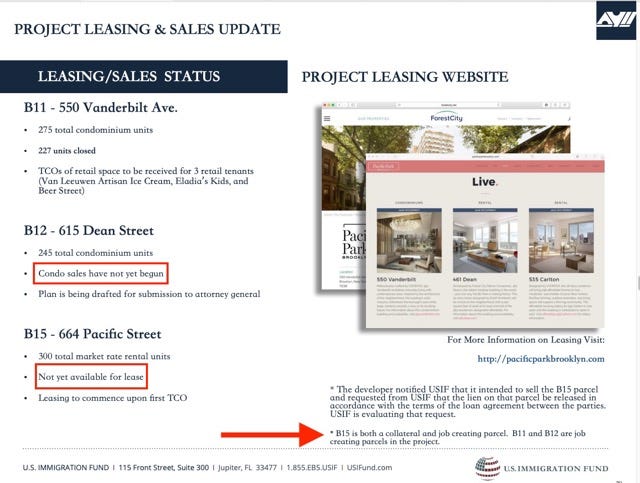

Still, the USIF kept up the charade in the slide below. Regarding B12, it says “Condo sales have not yet begun.” Regarding B15, it says, “Not yet available for lease.”

Given that neither building was under construction, those claims were not inaccurate but fundamentally untrue, as if I were to say, “I have not yet made my NBA debut.”

More evidence

In early 2019, a redeployment brochure sent to investors in “Atlantic Yards II,” suggesting where they might move some of their money, given the sale of one collateralized parcel (B15), maintained the claim.

It stated, as indicated in the highlighted section above, that “construction spending activities” on B3, B11, B12, and B15 satisfied job-creation requirements.

Looking at the spending

Another document provided to investors, dated Nov. 1, 2018, claims to calculate the economic impact of constructing the aggregated project known as “Atlantic Yards II.”

The subject is “Economic Impact of Construction of Several Mixed-Use Buildings and Associated Properties at Atlantic Yards, Brooklyn, NY, as Part of an EB-5 Regional Center in the New York City Metropolitan Area.”

It was produced by the consulting firm Evans, Carroll & Associates, of Boca Raton, FL, which works with the USIF.

Note that no job count is required. Under the Regional Input-Output Modeling System (RIMS II), an economic model, the jobs are calculated by applying a “multiplier” to the money spent.

Thanks to generous EB-5 rules, the money subject to the multiplier includes not just the EB-5 investment but also other “project” funds.

The memo estimates that 6,091 jobs had created by the “project” since its inception. as indicated in the orange outline, including 470 in the one year ending Sept. 30, 2018. This is referenced in the redeployment brochure, which states, “Per the recent economic report, 6,091 jobs have been created to date.”

The total appears to be a reasonable cushion over the 4,980 jobs—ten per investor—required under EB-5 regulations.

A big switch

The second column, outlined in green, indicates spending in current dollars: $481,638,000 for residential construction, and $29,898,000 for architectural and engineering services.

That total, $511,536,000, suggests that the $249 million raised by the immigrant investors represented nearly half, or 48.7%, of the total “project” funds.

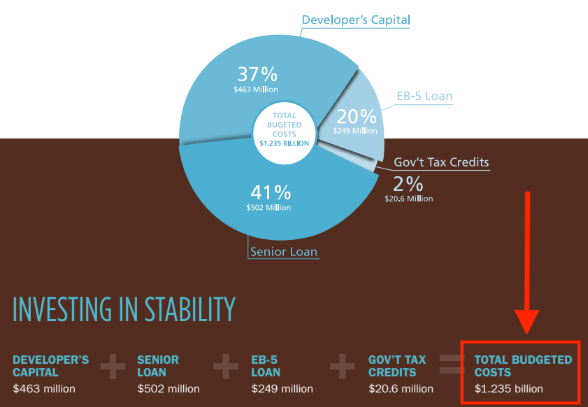

That’s not what investors were told. According to a 2014 brochure excerpted below, the “project” was to be $1.235 billion, which suggested that the EB-5 funds were a relatively small 20%—and thus safer—part of the capital stack.

An Evans, Carroll economic impact analysis, according to the USIF’s 2014 Offering Memorandum, predicted that the $1.235 billion “project” would create 9,738 permanent new direct, indirect and/or induced jobs.

Though the 2018 memo cited $511.5 million in spending, the original $1.235 billion was still projected in the USIF’s redeployment brochure, as indicated in the screenshot below.

How the money was spent

Another excerpt (below) from the 2018 Evans, Carroll memo states that, for the permanent railyard, the “project” spent $167,567,891 through Sept. 30, 2017, and another $26,760,990 in the next year.

That total, $194.3 million, represented about 38% of the $511.5 million cited below. That was, within state guidelines and fulfilled the prediction by Forest City Ratner CEO MaryAnne Gilmartin that the EB-5 funds would be spent on infrastructure.

However, the rest of the spending, more than $316 million on B3, B3 parking, and B11, violated the restrictions in the ESD’s Consent Letter.

Did Evans, Carroll know that? My query didn’t get a response.

Was the money equally distributed?

There’s no reason to think the $249 million in EB-5 funds was distributed evenly among those four job-creation elements, accounting for 48.7% of spending at each.

Why is it unlikely that immigrant investors contributed some $63 million—48.7% of the $130 million spent—on the B3 tower? Well, it didn’t need that much money.

According to a 2017 Forest City document submitted to the Securities and Exchange Commission, 38 Sixth, or B3, was expected to cost $202.7 million. (Not $130 million.) Most of that funding, according to a June 2, 2015 memorandum from the New York City Housing Development Corporation, was already accounted for.

The document cites $87,000,000 in bonds, $11,915,000 in two subordinate loans, $79,500,000 in equity, and $19,700,000 of borrower’s equity repaid from Low Income Housing Tax Credits. That’s more than $198.1 million—or nearly the total budgeted. That leaves little room for direct funding from the EB-5 investors.

EB-5 as catalyst?

Loose federal EB-5 rules allow investors job-creation credit even if their funds represent only a fraction of a “project.”

But unless that EB-5 money was truly a catalyst to get the building started—and, remember, B3 was negotiated by the city before the EB-5 funding was secured—it shouldn’t merit that credit.

Again putting aside the state conditions which disallowed the spending, such federal job-creation credit is plausible only if, as NYU scholar Gary Friedland observed, “development and construction of the project would not proceed without EB-5 capital, a position that few project developers could likely demonstrate.”

What about the railyard?

Perhaps most if not all of the $194.3 million in reported railyard spending came from the EB-5 loan. It’s also possible that the additional $100 million in the “Atlantic Yards III” EB-5 project went to the railyard.

But why wasn’t all of the $249 million loaned in “Atlantic Yards II” spent on the railyard?

That would have been consonant with the Consent Letter and would reflect comments made by an ESD staff lawyer, who, at last month’s meeting of the Atlantic Yards Community Development Corporation, brushed off concerns about improper spending by noting that “there was a massive amount of construction in the railyard.”

The job-creation calculation

But that might not have comported with EB-5 job- creation requirements, I speculate, given the dubious misclassification of spending.

The spending summary below, from Evans, Carroll, is segmented into residential construction and architect & engineering services.

Work on B3 and B11—though not permitted by the Consent Letter—would qualify as “residential construction.”

What about the “Permanent Yard”?

There's no reason to think that railyard work qualifies as "residential construction" under the NAICS (North American Industry Classification System) code 2361, as indicated in the excerpt above from the Evans, Carroll memo.

A look at 2361 - Residential Building Construction, shows that the subcategories include Single-Family Housing Construction, Multifamily Housing Construction, New Housing For-Sale Builders, and Residential Remodelers.

That doesn't include a railyard.

A separate code 2362 - Nonresidential Building Construction, might come closer, as it includes: Industrial Building Construction and Commercial and Institutional Building Construction. Or maybe 237210 - Land Subdivision, and related activities, such as installing utilities, comes closer.

Why the choice?

Choosing Residential Construction likely offered an advantage. A December 2013 RIMS II User Guide produced by the U.S. Department of Commerce's Bureau of Economic Analysis indicates, as shown in the annotated screenshot below, that residential construction adds more value than non-residential construction.

That suggests non-residential construction deserves a lower multiplier, and thus would create fewer jobs. So, had they more accurately classified the spending on the railyard, it likely would've generated fewer jobs, perhaps too few to meet federal minimums.

The original $1.235 billion “project,” as cited in the USIF’s 2014 Offering Memorandum was supposed to easily meet job-creation requirements: ”Up to 9,738 jobs are estimated to be created by the Project, which is substantially greater than the 4,980 minimally required jobs.”

Later, however, the job-creation calculation was based on $511.5 million, or 41.6% of the previously projected spending.

Note that the Evans, Carroll memo did not conclude that such spending created 41.6% of the originally jobs estimated, or 4,051. That wouldn’t have met the federal threshold.

Rather, the 6,091 jobs calculated represent 62.5% of the original 9,738 total, though based on 41.6% of the spending that triggered the higher estimate.

(Without seeing the details of the original estimate, however, it’s not possible to definitively compare the two calculations.)

About job calculations

Whatever the numbers, the calculations don’t reflect real-world head count. Even the direct jobs--more than 3,400 workers, in job-years, to build two towers and the railyard--begs credulity.

Beyond that, the use of indirect and induced (created by worker spending) jobs is dubious, as scholars and federal reports have concluded.

According to a 2013 memo from Homeland Security Investigations (HSI), an investigative arm of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement :

HSI conducted research using job creation statistics used by large corporations and the U.S. government stimulus package, and has reason to believe that the RCs [regional centers] are greatly exaggerating their indirect and induced job creation figures. By not having to provide evidence of jobs directly created, the RC inherently creates an opportunity for fraud, where the business goal can be initiating projects that give the appearance of creating job growth, with the sole intent to meet USCIS criteria rather than produce jobs.

Federal investigations, not surprisingly, have focused on blatant misappropriation of EB-5 funds. However, as HSI suggested, job-creation calculations also deserve scrutiny.