Asleep at the Watch on the EB-5 Loans

Had NY State done required due diligence on the transactions and/or the spending, it might have staved off foreclosure.

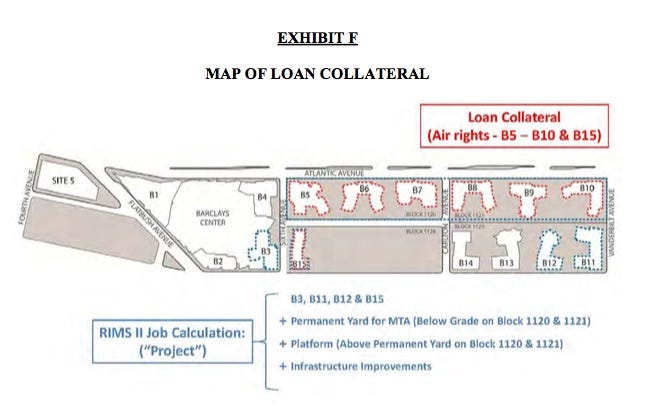

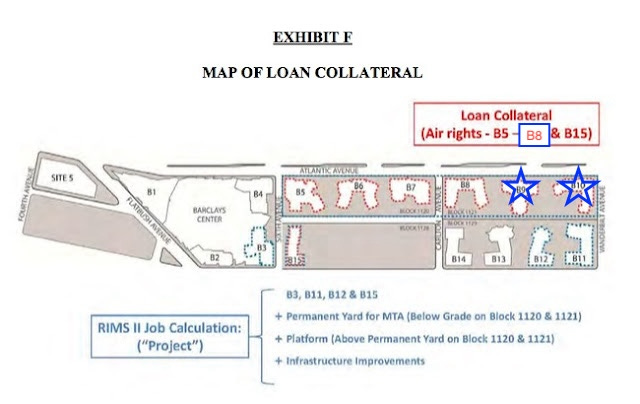

Given the announced foreclosure sale—postponed until Feb. 12—of developer Greenland USA’s interest in six parcels over the Vanderbilt Yard (B5-B10) and a public meeting tomorrow regarding that sale, I’ll offer two related newsletters today.

I wrote earlier today about the sketchy promotion of EB-5 investments and the state’s willingness to go along with it.

The foreclosure might have been avoided, of course, if the developers had been more fortunate in their business, and proceeded to build the project as proclaimed. (Or maybe if they’d continued to raise more EB-5 monies?)

But evidence suggests that it also might have been averted if Empire State Development (ESD), the state authority that oversees/shepherds the project, performed the due diligence that its contracts required.

Three take-aways

Let me summarize three conclusions from this article.

First, when Greenland Forest City Partners (GFCP), via the loan packager (aka “regional center”) U.S. Immigration Fund, went back to Chinese EB-5 investors for $100 million and diluted the collateral previously put up for a $249 million loan, ESD should have gotten proof the same collateral could now support $349 million in borrowing.

Second, when Greenland in 2018 was paid $55.83 million for one parcel used as collateral but indicated that the appraised value was $63.16 million, ESD should’ve noticed that the overall loan was insufficiently collateralized.

Third, when GFCP failed to deliver required annual reports on how the loan funds were spent, ESD should’ve required those reports, then looked more closely.

Instead, it belatedly accepted a report with assertions, rather than evidence, 4.5 years late. Moreover, the production of that document was surely triggered by my Freedom of Information (FOIL) request.

Part I: Monitoring the Transactions

Evidence suggests, at two junctures--one in 2015 and another in 2019--ESD whiffed on the requirement to support the fiscal soundness of proposed transactions.

In other words, Greenland Forest City Partners should not have been given the green light to make the second loan, not without further evidence. That's because the loan diluted the existing collateral rather than adding new collateral.

Nor should GFCP, dominated by Greenland USA rather than original developer Forest City Ratner, have been permitted to market the B15 site, previously used as collateral, without the state taking a closer look.

That because, while a state document required the value of the B15 site to be 25% more than the portion of the loan associated with it, the transaction showed the value was actually less.

Both episodes support the conclusion that the collateral for the $349 million borrowed, rather than providing investors a cushion, was instead insufficient.

Consent Letter requirements

Both the $249 million transaction (aka "Atlantic Yards II") and the $100 million transaction (aka "Atlantic Yards III") both contained clauses in the Consent Letters issued by ESD that imposed potential restrictions on future transactions.

(Here’s the Sept. 9, 2014 Consent Letter for the first loan and the June 17, 2015 Consent Letter for the second loan.)

While the loans were outstanding, the borrower--an affiliate of the joint venture -could not transfer any portion of its ownership or leasehold interest in the collateral if the loan’s new balance would exceed 80% of the collateral’s value.

That was known as the Leverage Requirement. It seems parallel to the Loan to Value (LTV) ratio, a common factor, according to Investopedia, in determining eligibility for private homeowners securing a mortgage and setting an interest rate.

An LTV ratio over 80% is a red flag, prompting higher interest rates or requiring private mortgage insurance.

In this case, the interest rate was low, whatever the risks, given that the lenders, immigrant investors, care more about green cards than financial return. But the Leverage Requirement was aimed, it seemed, to ensure that the loan was sound.

What was the collateral?

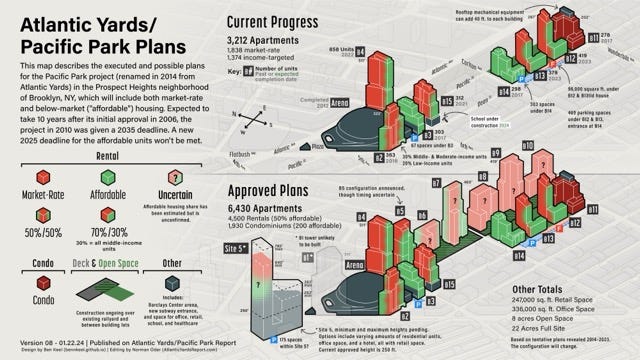

That collateral constituted the B15 site just east of Sixth Avenue between Dean and Pacific streets, now home to the 662 Pacific Street tower, and the sites B5 through B10 over the two blocks of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority's (MTA) Vanderbilt Yard.

The latter six sites require an expensive platform before construction, as well as payment to the MTA for development rights.

For any transfer, the borrower and owner had to provide ESD 30 days’ prior notice of such Transfer, plus evidence that the Leverage Requirement would be satisfied.

I filed a FOIL request seeking documents that confirm such written evidence had been provided. ESD told me it had no responsive records. So it seems they ignored the requirement.

Diluting the collateral

That’s unwise. Evidence suggests they shouldn't have allowed the second EB-5 loan at all, since it lowered the value of the collateral.

Consider: the first loan, $249 million, was collateralized by seven parcels, B5-B10, plus B15. At an 80% LTV ratio, the minimum appraised value of the collateral should’ve been $311.25 million.

For the second loan, worth $100 million, the collateral was divided, and diluted. The initial $249 million would now be backed by parcels B5-B8, plus B15. The second loan, $100 million, would be collateralized by parcels B9 and B10.

If you wonder whether two parcels delivering 1.15 million square feet might not be worth $100 million, remember that to unlock that requires significant spending on a platform and payment to the MTA for development rights.

To maintain the 80% LTV value for the seven parcels, the collateral should by then have been worth $436.25 million in total.

There’s no evidence ESD got proof of that.

A telling transaction

Later, the EB-5 middleman, the USIF, took its own responsibility to maintain the Leverage Requirement and, in doing so, undermined—by my reading—the value of the collateral.

In December 2018, Greenland USA, by then owner of nearly all the project, sold the B15 lease to another developer, The Brodsky Organization, for $55,830,000, according to city records.

To do so, the borrower requested release of the lien on that parcel, according to a USIF message to investors. So a USIF affiliate looked into whether the sale would bring the borrower out of compliance with that 80% Leverage Requirement.

"The appraisal," investors were told, "confirmed that the proposed sale of B15 would require that the borrower partially repay the EB-5 loan, in an amount equal to the appraised value of the released parcels, equal to $63,160,000."

The red flag

That, in retrospect, should have been a red flag for Empire State Development. The $55.83 million value of the collateral, in this case, was less than the $63.16 million appraised value. (In other words, the appraised value should’ve been matched by reality.)

The borrower apparently had to repay investors with additional funds, beyond the sales transaction.

If the sale value of the remaining collateral was similarly less than the appraised value, the loan shouldn't have been approved in the first place.

After all, with an 80% Leverage Requirement, the sale of collateral should deliver extra cash, rather than—as in this case—insufficient funds.

That suggested that the loan, rather than 80% of the collateral's value, instead exceeded that value—a sign of risk.

Doing the math

Let’s look at the $249 million loan in the most generous possible light: that the five parcels at issue generated collateral, at an 80% Leverage Requirement, worth $311.25 million.

Subtract $63.16 million, or 25.37%, representing B15’s share, returned to investors from $249 million. That leaves $185.84 million outstanding.

To maintain the 80% Leverage Requirement, the appraised value of the remaining four sites (B5-B8) should be at least $232.3 million.

Is that collateral worth $232.3 million? Based on the B15 transaction, very unlikely.

Consider: the $55.83 million paid represents 25.37% of $220.06 million. That sum is less, not more, than the $249 million borrowed.

The Leverage Requirement means that the collateral should always be worth more than the amount borrowed. But there’s no evidence that ESD kept watch.

Looking back

If the collateral now seems to have been worth just $220.06 million, the whole EB-5 loan structure collapses.

At an 80% Leverage Ratio, the revised loan for “Atlantic Yards II”—after dilution of collateral—should have been $176.49 million, not $249 million.

Another way to look at it: subtract $55.83 million paid from the $220.06 million collateral, leaving the collateral’s remaining value at $164.23 million.

That's well less than the $185.84 million owed to “Atlantic Yards II” investors. To truly maintain an 80% leverage ratio, the collateral should be worth at least $232.3 million.

Alternatively, the current $164.23 million collateral, at an 80% Leverage Ratio, supports an ongoing loan of just $131.38 million.

Part II: Monitoring the Spending

So, what was the $349 million in EB-5 funds spent on?

As quoted in a promotional video for the $249 million in “Atlantic Yards II,” Forest City Ratner CEO MaryAnne Gilmartin told potential investors, “Given the success of that first EB-5 raise, we are focused on a second raise that will allow us to continue the infrastructure development portion of the project.”

New York State was supposed to be informed of that spending. An accurate account of that spending might have alerted it to the precarious financial state of the project.

“Permitted uses”

According to the Consent Letter, the loans to AY Phase II Mezzanine and AY Phase III Mezzanine (affiliates of Greenland) had constraints.

Because the Lender was not a Lending Institution, as defined in the project’s Interim Lease, the Equity Pledge constituted a Transfer that required ESD’s consent. The latter offered such consent, but only for “Permitted Uses.”

The 2014 document allowed a rather expansive use for the $249 million:

the acquisition of the MTA Air Space Parcel, the six tower sites over the Vanderbilt Yard

a permanent railyard for the Long Island Rail Road

a platform over the railyard to enable tower construction

residential buildings on the "Mezzanine Encumbered Properties"

additional infrastructure, site work and environmental remediation with respect to the latter sites

That, of course, would cost way more than $249 million. The platform alone could cost $300 million—and hasn’t yet started.

Note that the "Mezzanine Encumbered Properties" were the six tower sites (B5-B10) over the railyard, as well as the B15 site across from the arena block.

The railyard sites, obviously, didn’t start, because they require a platform.

While preliminary work on B15, including an architect's presentation, did take place in 2015, necessitating some spending on soft costs, construction did not start until 2019, after the site was leased to Brodsky Organization.

Dilution into Class A and Class B

As I wrote, the 2015 document for the $100 million “Atlantic Yards III” loan redefined the "Mezzanine Encumbered Properties," since there were now two classes of membership interest in Owner, Class A and Class B.

The lenders of the first loan would now only have the right to parcels B5, B6, B7, B8 and B15 as collateral, while the lenders of the second would have the rights to parcels B9 and B10.

So the value of the collateral for the first loan went down significantly.

Reporting requirements

Each document required seemingly annual reports.

The 2014 Consent Letter required that, within a month after each year’s start, the Borrower "shall provide ESD evidence, which shall be reasonably acceptable to ESD, (i) of each advance of Loan proceeds made during the prior calendar year, and (ii) that such Loan proceeds have been utilized for a Permitted Use."

Failure by Borrower to provide that evidence within three months after the reporting date "shall, at the election of ESD, comprise a default," though that default could be cured by a borrower's response.

So that left some slack—though it didn’t give them carte blanche.

Additional milestones

The 2015 Consent Letter added Milestone Requirements for the combined loans:

by the end of 2015, at least $52,350,000, or 15% of the total proceeds, should have been incurred and paid for Permitted Uses

by the end of 2016, at least $139,600,000, or 40% of the proceeds, should go to Permitted Uses.

by the end of 2017, at least $261,750,000, or 75% of the proceeds, should go to Permitted Uses.

Acquiring the MTA air rights?

The borrower "shall use commercially reasonable efforts to complete all conditions precedent to the acquisition” of the MTA Air Rights—presumably the new railyard and payment for development rights—by the end of 2017.

Within 90 days of completion of such Conditions Precedent, the developer was supposed to complete the acquisition of that MTA Air Space Parcel, subject to MTA’s compliance with its obligations.

But that made no sense.

According to the June 22, 2009 MTA Staff Summary regarding the railyard deal, Forest City would then pay $20 million for the piece of the property where the arena would be built (in part).

The remaining $80 million present value would be paid, at an implied 6.5% interest rate, in four $2 million installments 2012 through 2015, then 15 annual installments of about $11 million each beginning on June 1, 2016.

In other words, they had—and have—until 2030 to pay for railyard development rights. The only reason to have accelerated that would be unusually favorable development conditions. Instead, the opposite applied, with a glut of competing product from Downtown Brooklyn.

What’s “commercially reasonable”?

The term “commercially reasonable” efforts, an ESD favorite, should have been a red flag, at least to outside observers.

After all, in a November 2011 decision requiring the state authority—then known as ESDC rather than ESD—to study the impacts of an extended buildout, state Supreme Court Justice Marcy Friedman pointed to the contrast between a requirement that the developer use "commercially reasonable" efforts to complete Atlantic Yards in a decade and a guiding Development Agreement that allowed 25 years, until 2035:

In short, ESDC’s invocation of the commercially reasonable effort provision rings hollow in the face of the specific deadlines in the Development Agreement... that may extend beyond the purported 2019 build date for 16 years, until 2035.

The court accordingly finds that ESDC’s use of the 10 year build date in approving the 2009 MGPP lacked a rational basis and was arbitrary and capricious.

Were reports actually filed?

Within 30 days after each “Milestone Date,” the borrowers were supposed to provide ESD evidence, “which shall be reasonably acceptable to ESD,” that the applicable Milestone Requirement was met.

Were those annual reports actually submitted? To find out, I filed a Freedom of Information Law request with ESD on April 18, 2019.

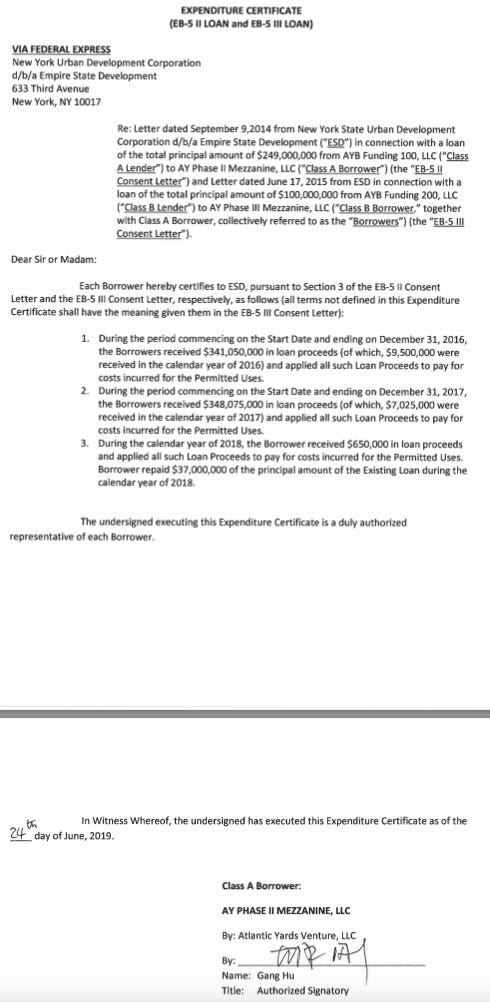

I got a response July 3, 2019, which included an Expenditure Certificate, signed by Greenland USA's Gang Hu, dated June 24, 2019—after the date of my inquiry.

It ignored the requirements to deliver reports in the first month of 2015 and 2016 but instead certified:

1. During the period from the Start Date through 2016, the Borrowers received $341,050,000 in loan proceeds, including $9,500,000 in 2016.

2. Through 2017, the Borrowers received $348,075,000 in loan proceeds, including $7,025,000 in 2017.

3. During 2018, the Borrower received $650,000 more in loan proceeds. That year, the Borrower also repaid $37,000,000 of the principal. (Later, in 2019, the Borrower’s repayment would total $63,160,000.)

In each case, the Borrowers "applied all such Loan Proceeds to pay for costs incurred for the Permitted Uses."

Reasons for doubt

Beyond the after-the-fact timing, there are two questionable aspects to that.

First, the delay. If the sole Expenditure Certificate was dated June 24, 2019, well after all the money was dispersed, no such Expenditure Certificates were provided annually, as required.

That meant ESD had no inkling whether its “Permitted Uses” were being met.

Second, despite the requirement to "provide ESD evidence," no such evidence—details, charts, receipts—was provided in the Expenditure Certificate. Unsupported claims was accepted.

Yes, the Consent Letters say the evidence "shall be reasonably acceptable to ESD," a phrasing that offers wiggle room. Had ESD been informed that the money was spent impermissibly, or demanded evidence, it could've pursued sanctions. Instead, it seems to have deliberately put on blinders.

Following up

I did try again.

I filed another Freedom of Information Law request, asking for documents that represented the evidence that each advance of loan proceeds have been utilized for a permitted use and that represented that Milestone Requirements were met appropriately.

ESD's response: the previously supplied Expenditure Certificate confirmed that Milestone Requirements were met, but it had no responsive records regarding my other queries.

You just have to take their word for it.

Great piece Norm. Coincidentally after reading this article I received an email from the New Yorker with a new piece about EB-5 loans and their consequences in Vermont. Wonder if same parallels can be drawn with AY.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2024/02/05/the-rural-ski-slope-caught-up-in-an-international-scam?utm_source=nl&utm_brand=tny&utm_mailing=TNY_Daily_013124&utm_campaign=aud-dev&utm_medium=email&utm_term=tny_daily_digest&bxid=5d34c8f2bf008151a625259f&cndid=57921732&hasha=b9c5b1fbd6e47b2d5b4c4457b78f5db3&hashb=e139b517772042c244ceb551cbc3b66c5800016a&hashc=377c58d86526e4118aa22df1a2a5d88d9b1a75cb52cea7f720151f92b10bccf1&esrc=Auto_Subs&mbid=CRMNYR012019