A "Garden of Eden"? Revisiting a NY Times Rave for the 2003 Atlantic Yards Debut

Architecture critic Herbert Muschamp was so dazzled by Frank Gehry's designs he suspended skepticism and got much wrong.

This draws on my writing from 2006 and 2009.

“A Garden of Eden grows in Brooklyn,” rapturously wrote New York Times architecture critic Herbert Muschamp in his Dec. 11, 2003 appraisal of Atlantic Yards, a day after the project was unveiled. (Surely he’d been fed the plans earlier.) It was published on the front of the Metro section.

The arena-cum-towers project would be designed by Frank Gehry, whom the critic had vaulted into the stratosphere with his 1997 rave for the architect’s Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain.

Muschamp’s gushing essay, Courtside Seats to an Urban Garden, was soon used—er, misused—by developer Forest City Ratner in a flyer it sent to thousands of Brooklynites over the Memorial Day weekend in 2004.

Atlantic Yards, according to the brochure, would contain “almost everything the well-equipped urban paradise might have.” That was misleadingly credited to the Times, not the particular critic.

(I wrote separately about the Atlantic Yards unveiling, souce of several of the images below.)

Why Muschamp mattered

The distinction between critic and editorial voice was important, because Muschamp, the paper’s architectural arbiter from 1992 to 2004, had a notably cozy relationship with Gehry and was known—and derided—for focusing on starchitects. Moreover, in his column Muschamp failed to disclose the parent Times Company's connection to Forest City.

Not only was Muschamp sloppy and overenthusiastic, his focus was wrong. "The cultural dimension of building stirs me emotionally. I have minimal interest in personalities or politics," Muschamp once pronounced, adding that "the practicalities do not lack outspoken advocates."

Still, Atlantic Yards deserved a review that assessed not just the esthetics of Gehry’s designs, but also the issues of urbanism recognized by other critics, such as the Times’s current critic, Michael Kimmelman or the Philadelphia Inquirer’s Inga Saffron, who’s written incisively about a proposed new downtown arena in Philadelphia.

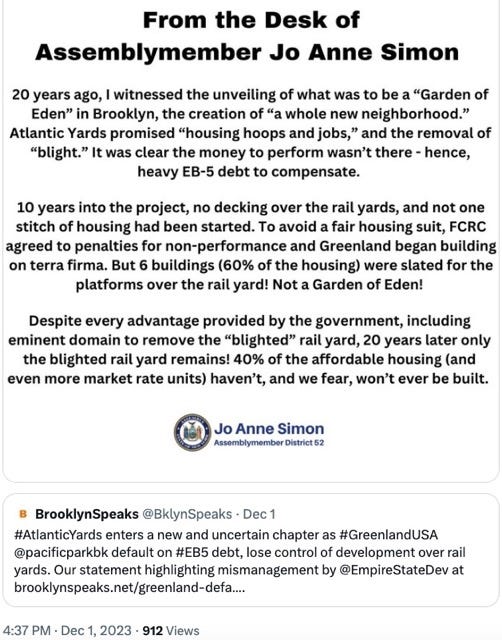

That “Garden of Eden” quote stuck so much it recently surfaced in a statement from Assemblymember Jo Anne Simon, criticizing the gap between Muschamp’s projection and the reality of a stalled project.

Looking at the review

Though the initial Atlantic Yards plan was preliminary, Muschamp's review was conclusory. It began:

A Garden of Eden grows in Brooklyn. This one will have its own basketball team. Also, an arena surrounded by office towers; apartment buildings and shops; excellent public transportation; and, above all, a terrific skyline, with six acres of new parkland at its feet. Almost everything the well-equipped urban paradise must have, in fact.

He expressed no doubt regarding how the “paradise” might work, whether the "parkland"—actually, publicly accessible, privately operated open space—would be sufficient for the new population, or, as we now known in hindsight, whether the project was viable as proposed.

Great urban design?

Muschamp continued:

Designed for the Brooklyn developers Forest City Ratner Companies by Frank Gehry with the landscape architect Laurie Olin, Brooklyn Atlantic Yards is the most important piece of urban design New York has seen since the Battery Park City master plan was produced in 1979.

Even then, that was unwise. Unmentioned: the Battery Park City master plan was produced before a developer was chosen, while the Atlantic Yards design was formulated by a developer (who hired an architect and landscape architect) and presented to the public.

Forest City’s track record

Muschamp didn't tell his readers that Forest City Ratner had a checkered track record architecturally in Brooklyn, developing the sterile MetroTech complex and the blank-walled Atlantic Center mall. Those were business decisions.

So too was vaulting the architecture to a new level. As it turned out, despite hiring Gehry, whose design was later ditched for a smaller, cheaper arena, Forest City was still ruled by the bottom line. (They were savvy enough, though, to rescue that design with a new exterior from SHoP.)

Muschamp also likened Atlantic Yards to another 22-acre, mixed use project: Rockefeller Center, without recognizing a key contrast. Atlantic Yards would demap city streets and create superblocks (an oft-criticized concept), while Rockefeller Center added a street, creating more liveliness for pedestrians.

A fundamental error

Muschamp described the project footprint:

The six-block site is adjacent to Atlantic Terminal, where the Long Island Rail Road and nine subway lines converge. It is now an open railyard.

This was a key error, which the Times, confoundingly, refused to correct. The railyard, with a southern boundary at Pacific Street, would occupy less than 40% of the site, which extends a block below, to Dean Street.

Did Gehry, who once described the footprint as "an empty site," get it wrong and mislead Muschamp? Did the critic succumb to Forest City Ratner p.r., which misleadingly portrayed the site as limited to the railyard, as shown in the image below?

Or Muschamp simply never cross the river to visit the site?

His description erased the homes, businesses, and streets that would be subsumed by the project. Atlantic Yards would’ve proceeded with far less controversy and far fewer roadblocks had the site, indeed, been just “an open railyard.”

Who’s the planner?

Though Muschamp observed, obliquely, that “a large-scale urban development… enables planners to rethink how communities want to live,” that glossed over the lack of previous planning for the railyard, which had never been put out for bid, much less the larger outline drawn by Forest City.

It also ignored the strategy to have the Empire State Development Corporation, a gubernatorially controlled state authority, avoid the city's land use review process, wielding the power of eminent domain to both pressure property owners to sell and, ultimately, to condemn properties.

More importantly, in retrospect, the critic failed to remind readers of the challenges—not just the opportunities—facing megaprojects. We now know the importance of candor regarding such projects, as well as ongoing oversight.

What was the “wow”?

To Muschamp, “The design's most exceptional feature is the configuration of office towers surrounding the arena.”

He was expecting that the towers would offer access to the arena’s green roof, and would be emptied of occupants when arena events took place, in the evenings and weekends.

However, three of the towers would soon be converted to housing and the fourth, the flagship that Gehry dubbed “Miss Brooklyn,” was never built, leaving a plaza—a canvas for sponsors and advertising—that was introduced as temporary but surely will be permanent.

Muschamp also welcomed the “Urban Room” atrium, “a soaring Piranesian space, which provides access to the stadium and a grand lobby” for that flagship tower. But that never got built, and the plaza has proved crucial to arena functioning.

Back in 2006, I suggested that a critic should muse on whether people would welcome living next to an arena, with its noise and crowds and neon. Today, I’d acknowledge that it hasn’t deterred people living in the three towers flanking Barclays.

Getting on the roof

Another wow, to the critic, was the planned public running track/skating rink and recreation area on the arena’s green roof—an impressive concept that was attenuated, then discarded.

By 2006, Forest City acknowledged the space would be limited to those in the surrounding buildings. Later the entire concept was value-engineered.

When the arena opened in 2012, it had a rubber roof with a Barclays Center logo. But it got a green roof—er, brown in season—by 2015. But that’s mostly to tamp down noise, given that bass-heavy concerts in the initial years somehow turned the arena into a giant neighborhood sub-woofer.

The buildings and the “garden”

Muschamp also enthused about Gehry’s proto-skyline of “big cube buildings,” suggesting they had “a toughness that looks right for New York at this uncertain moment in time.”

That was a stretch, given the decontextualized nature of the renderings.

Moreover, the critic might better considered what the buildings might look like in a decade (or more), given the announced ten-year buildout and the riskiness of such optimistic prognostication.

Since then, the Downtown Brooklyn skyline has far eclipsed Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park. (I’ll write about that separately.)

Conflicts unmentioned

It became standard procedure for Times articles about Atlantic Yards plan to disclose that developer Forest City Ratner and the parent New York Times Company were partners in building the new Times Tower on Eighth Avenue.

In the early days of writing about this project, however, several articles lacked this disclosure, notably Muschamp's appraisal.

Would that have changed Muschamp’s rave? Perhaps not the author’s draft. But it might have reminded his editors to look more carefully.

Lost to history

Muschamp died in 2007. When a 912-page doorstopper collection of his work, Hearts of the City: The Selected Writings of Herbert Muschamp, was released in 2009, it omitted his Atlantic Yards appraisal. Credit the book's editors, perhaps, for spotting a dud while shaping a compendium of the critic’s work.

Then again, maybe they should have included that Atlantic Yards appraisal, given Muschamp's connection with Gehry. After all, as Muschamp’s successor Nicolai Ouroussoff wrote in his introduction:

It was Frank Gehry's work, however, that brought out Muschamp's most rapturous writing. Muschamp sometimes referred to Gehry as a father figure, and he saw him as the standard bearer of an American, democratic architecture.

...The dream reached its fullest expression in Gehry's design for the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, which Muschamp summed up in a review [The Miracle in Bilbao, Sept. 7, 1997] that for many came to define his unchecked exuberance.

It did not reach its fullest expression in Brooklyn, or Muschamp’s enthusiasm for Atlantic Yards.

But that’s part of his history, and ours.