The Failure to Do Due Diligence on the Second EB-5 Loan Looms

New York State's (partial) defense of its oversight didn't address why it allowed dilution of the developer's collateral. That question should be asked.

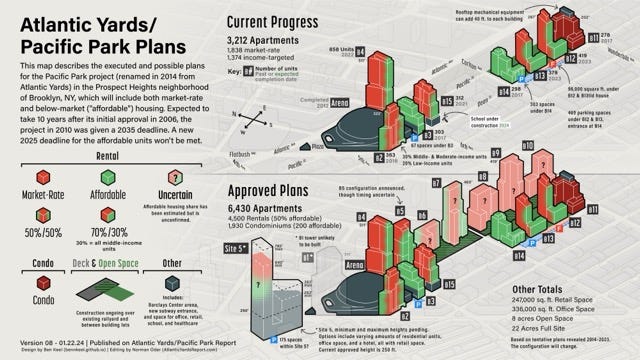

Master developer Greenland USA faces an auction, scheduled for April 30 (after two postponements), of six development sites over the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s Vanderbilt Yard.

Will it happen? Who knows. I wouldn’t bet against another postponement, given the complexity of unlocking the value of those sites.

But it’s easier to conclude that at least part of the mess might have been staved off with better state oversight.

That issue was not fully addressed at last week’s meeting of the Atlantic Yards Community Development Corporation (AY CDC), set up to advise the parent Empire State Development (ESD), which oversees/shepherds the project.

Let’s recap.

Greenland has defaulted on two loans, $249 million and $100 million, from immigrant investors under the EB-5 investor visa program, organized by the U.S. Immigration Fund (USIF), a “regional center” or middleman.

The sum remaining is about $286 million, because part of the first loan was repaid.

The loans were marketed as “Atlantic Yards II” and “Atlantic Yards III,” because an earlier loan, via a different regional center, had already been marketed, and the name had a brand in China, source, as of then, of most immigrant investors.

Appropriate spending the focus

Last week’s discussion at the AY CDC focused on a different oversight issue, whether the loans had been spent on what ESD considered Permitted Uses, activities aimed at advancing the project.

Though I found strong evidence that the USIF had claimed the EB-5 “project” included spending on previous towers, which were not Permitted Uses, ESD accepted claims that all the EB-5 funds—a partial contributor to the vaguely defined EB-5 “project”—were spent on revamping the railyard.

ESD did not share the documentation it received. I then found evidence casting doubt that all the money was spent on the railyard.

No exit strategy

However, ESD did not receive—nor, apparently, request—the required annual reports on such spending, starting in January 2015. And that might have pointed to a red flag raised at the meeting.

“It must have been known for some time that there weren't going to be buildings appearing above the railyard in time to start generating income that could be used to take out the EB-5 investors with some permanent financing," observed AY CDC Director Gib Veconi, referencing an expected exit strategy that would help repay the loans.

"In our search for clarity on this," responded ESD executive Joel Kolkmann said, "we did not come across anything." That should’ve been indicated in the annual reports.

That’s part of the challenge faced by an array of new executives—Kolkmann, Arden Sokolow, and Anna Pycior—who are the state’s public interface on the project today, but have brief tenures and have encountered, apparently, a limited paper trail. That means a lack of institutional memory.

Asleep at the watch

Presumably there’s nothing in the file about a related—and more threshold—issue: the viability of the second EB-5 loan in this sequence, the $100 million in “Atlantic Yards III.”

So it’s worth revisiting part of my January essay, Asleep at the Watch on the EB-5 Loans: not Part II, Monitoring the Spending, which relates to the discussion last week, but Part 1, Monitoring the Transactions.

The developer, then Greenland Forest City Partners, should not have been given the green light to make the second loan, not without further evidence. That's because the loan diluted the existing collateral rather than adding new collateral.

While the first loan was outstanding, the borrower--an affiliate of the joint venture -could not transfer any portion of its ownership or leasehold interest in the collateral if the loan’s new balance would exceed 80% of the collateral’s value, according to an ESD requirement.

That was known as the Leverage Requirement. It seems parallel to the Loan to Value (LTV) ratio, a common factor, according to Investopedia, in determining eligibility for private homeowners securing a mortgage and setting an interest rate.

An LTV ratio over 80% is a red flag, prompting higher interest rates or requiring private mortgage insurance.

What was the collateral?

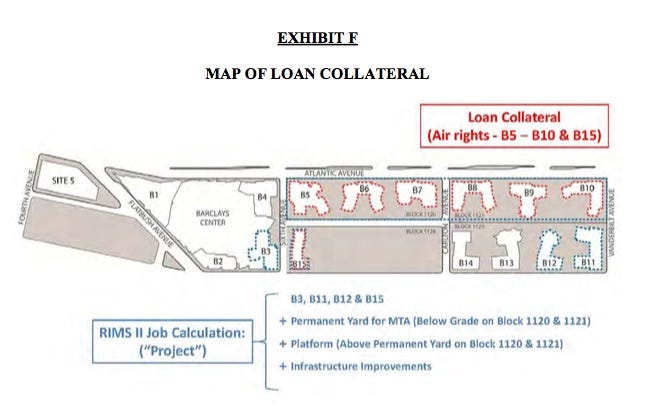

The initial collateral constituted the B15 site just east of Sixth Avenue between Dean and Pacific streets, now home to the 662 Pacific Street tower, and the sites B5 through B10 over the two blocks of the railyard. (Those railyard sites are in foreclosure.)

The latter six sites require an expensive platform before construction, as well as payment to the MTA for development rights.

For any transfer, the borrower and owner had to provide ESD 30 days’ prior notice of such Transfer, plus evidence that the Leverage Requirement would be satisfied.

I filed a FOIL request seeking documents that confirm such written evidence had been provided. ESD told me it had no responsive records. So it seems they ignored the requirement. But let’s see if current ESD leadership can confirm that.

Diluting the collateral

After all, evidence suggests they shouldn't have allowed the second EB-5 loan at all, since it lowered the value of the collateral.

Consider: the first loan, $249 million, was collateralized by seven parcels, B5-B10, plus B15. At an 80% LTV ratio, the minimum appraised value of the collateral should’ve been $311.25 million.

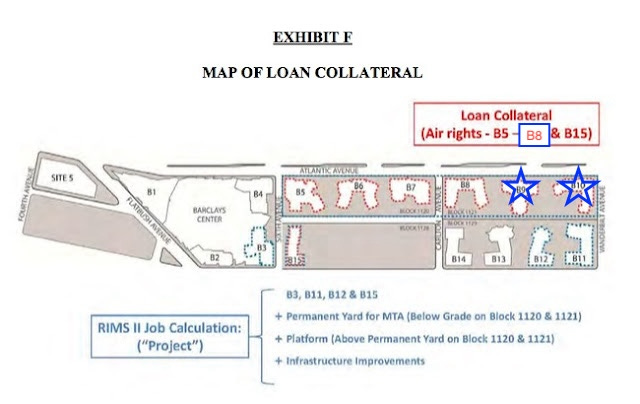

For the second loan, worth $100 million, the collateral was divided, and diluted. The initial $249 million would now be backed by parcels B5-B8, plus B15. Was that diminished collateral now worth $311.25 million unto itself?

The second loan, $100 million, would be collateralized by parcels B9 and B10. Was that now worth $125 million?

There’s no evidence ESD got proof of that.

A telling transaction

As I reported, the USIF later took its own responsibility to maintain the Leverage Requirement and, in doing so, undermined—by my reading—the value of the collateral.

In December 2018, Greenland USA, by then owner of nearly all the project, sold the B15 lease to another developer, The Brodsky Organization, for $55,830,000, according to city records.

To do so, the borrower requested release of the lien on that parcel, according to a USIF message to investors. So a USIF affiliate looked into whether the sale would bring the borrower out of compliance with that 80% Leverage Requirement.

"The appraisal," investors were told, "confirmed that the proposed sale of B15 would require that the borrower partially repay the EB-5 loan, in an amount equal to the appraised value of the released parcels, equal to $63,160,000."

The red flag

That, in retrospect, should have been a red flag for ESD. The $55.83 million value of the collateral, in this case, was less than the $63.16 million appraised value. (In other words, the appraised value should’ve been matched by reality.)

The borrower apparently had to repay investors with additional funds, beyond the sales transaction.

If the sale value of the remaining collateral was similarly less than the appraised value, the loan shouldn't have been approved in the first place.

After all, with an 80% Leverage Requirement, the sale of collateral should deliver extra cash, rather than—as in this case—insufficient funds.

That suggested that the loan, rather than 80% of the collateral's value, instead exceeded that value—a sign of risk.

The bottom line

Yes, real estate values can change over time, so it’s not impossible the value of the real estate diverged from the original appraised value. If so, ESD should’ve flagged that at the time, and kept watch.

And yes, sometimes appraisers can be “friendly” and deliver documentation that supports a deal. That could’ve happened at the outset of the loans.

It does not, however, look like ESD got evidence even to show such friendly appraisals.

It would be a logical continuation of the previous discussion at the AY CDC to ask if ESD did any due diligence on the second loan, thus ensuring that the 80% Leverage requirement was met.