New Developers Apparently Expect 1.6M Square Feet in Additional Air Rights for Free

"Today's context," they say, justifies bigger buildings. But the 2005 appraisal and bid for MTA development rights, in a different context, envisioned less bulk. Value of boost: $320M?

“Atlantic Yards in today’s context,” as proposed this week by the new development team, proposes 1.6 million more square feet of bulk, apparently in five much larger towers to be built over the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s Vanderbilt Yard, even as they eliminate an originally approved sixth tower.

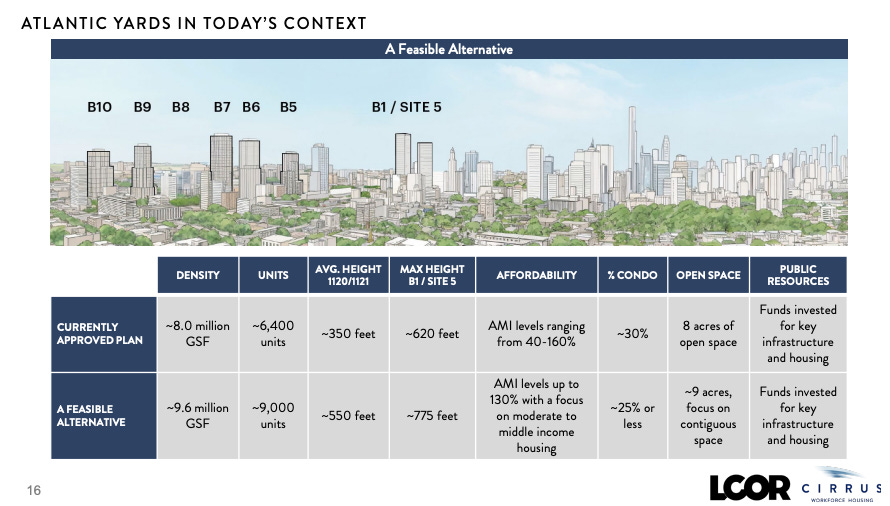

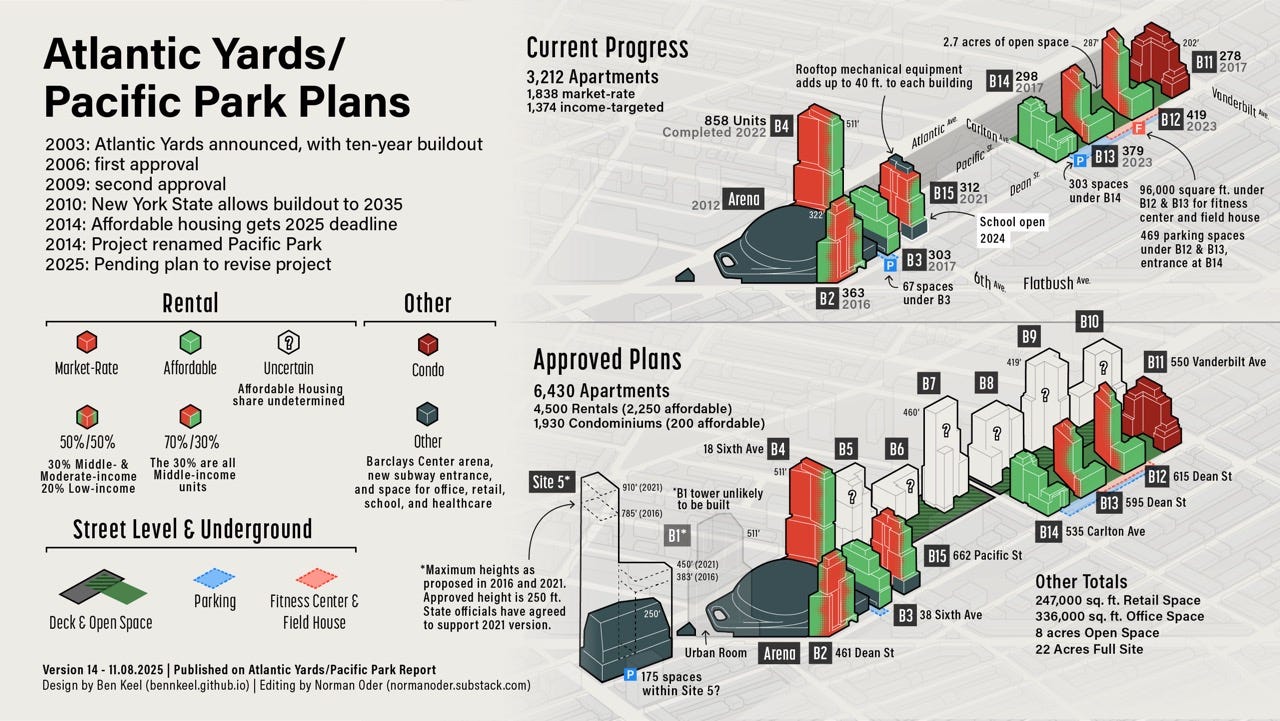

(Here’s my coverage, involving plans for some 9,000 apartments, compared with 6,430 as currently approved.)

That was posited as a “feasible alternative”—albeit not a final one— to the plan approved in 2006 and affirmed in 2009 by Empire State Development (ESD), the gubernatorially controlled economic development agency that can override city zoning and avoid the city’s land-use process.

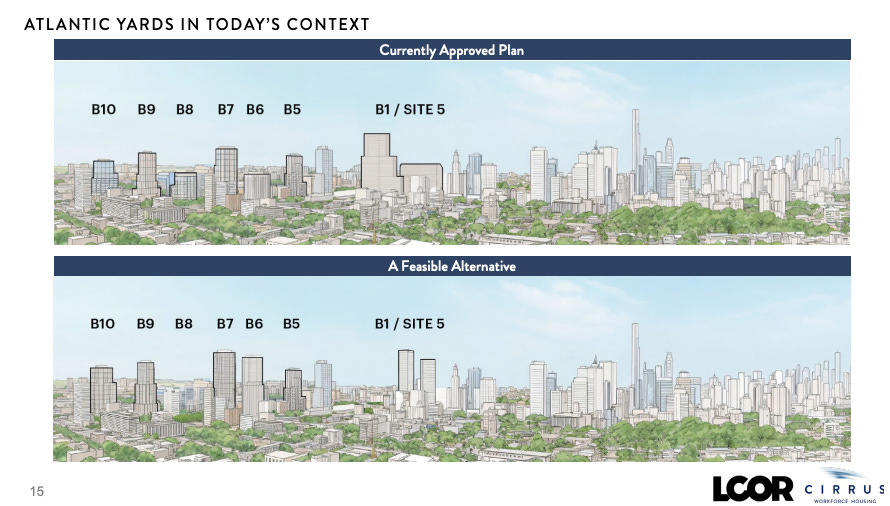

The “20% increase in overall density”—or, I calculated, 46% at the railyard sites—would be “contextual with the way that Brooklyn has changed in the last roughly 23 to 25 years,” asserted Joseph McDonnell, Managing Partner of Cirrus Workforce Housing, at a public workshop Nov. 18. (Funder Cirrus, with the development firm LCOR, is now the project’s master developer.)

That deserves discussion. Yes, Brooklyn—especially Downtown Brooklyn, to the west of Atlantic Yards, at right in the image above, which is a helicopter view looking south—has changed, especially from the Downtown Brooklyn rezoning. That rezoning, announced after Atlantic Yards was proposed, has delivered a new skyline.1

Yes, Atlantic Avenue, a major road, can absorb larger buildings than narrower streets. Yes, buildings averaging 550 feet tall as proposed, as opposed to 350 feet tall, may not be overwhelming, depending on how they “meet the street” and the quality of adjacent open space.

Then again, they may not be more conducive to family life, and one original selling point for Atlantic Yards was once supposed to serve working-class and poor families. Nor, as I’ll discuss separately, might additional open space, however better sited and designed, match the population increase.

Moreover, a perspective looking north or west—from the south or east of the project site—would show how Prospect Heights, the project’s location, connects to other neighborhoods and a context different from Downtown Brooklyn.

Would they pay for new bulk?

The context has changed for the development rights, too. In 2005, they were valued by an MTA appraiser at $75/buildable square foot (bsf), before subtracting infrastructure costs.

Thanks to the state’s ability to override zoning, the additional square footage, I estimated, might be roughly valued at $320 million, based on a ballpark figure of $200/bsf. That relies on a 2024 Brooklyn Market report from the brokerage TerraCRG.

So, would the developers have to pay for the additional valuable bulk--vertical “land”—that’s a public asset?

As architect/planner Vishaan Chakrabarti once told Curbed, “Look, there’s only two legal ways to create money in the United States: the Federal Reserve and an upzoning. So free FAR [Floor Area Ratio, a measurement of bulk] is worth its weight in gold.”

The answer I got from McDonnell implied they don’t expect to pay, as I recount below.

If so, that would constitute a significant subsidy for the project and should be factored into public analysis of the proposed plan—including, as seems necessary, third-party experts.

The backstory

Original Atlantic Yards developer Forest City Ratner had to win development rights in 2005, responding to an MTA Request for Proposals for the then three-block Vanderbilt Yard, totaling about 367,000 square feet.

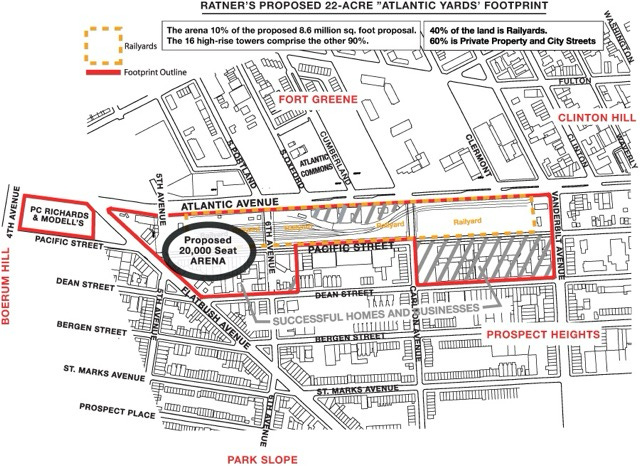

The image below, from Atlantic Yards opponents Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn (DDDB, now defunct), shows how the western third of the railyard would be used for the arena block. (The railyard, between Atlantic Avenue and Pacific Street, originally stretched east from Fifth Avenue to Vanderbilt Avenue.)

Ultimately, that western railyard block would serve as a base for a northern segment—maybe 40%—of the arena parcel (and plaza), as well as the tower known as B4 (18 Sixth Ave., aka Brooklyn Crossing), which does not require a platform and is built below grade.

The railyard functions—storage and service of the Long Island Rail Road cars—would be moved to the eastern block of the railyard, paid for by Forest City and, more significantly, its successor Greenland USA, which controlled a joint venture that Forest City ultimately left.

The central block is now the western of two remaining blocks, which require a platform. It would have fewer tracks and serve as a passageway for trains between the storage yard and Atlantic Terminal.

Bidding out the railyard

How does a developer acquire rights to build over an MTA railyard?

Well, Forest City long had the inside track, but political pressure—including from then-Council Member Letitia James, project opponents Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn, and the oppositional Brooklyn Paper—led the MTA to belatedly issue an Request for Proposals, or RFP.

Forest City, which had already gotten support for Atlantic Yards from the political firmament, bid $50 million cash. Upstart bidder Extell, recruited by DDDB, bid $150 million, with a less ambitious plan, sans arena.

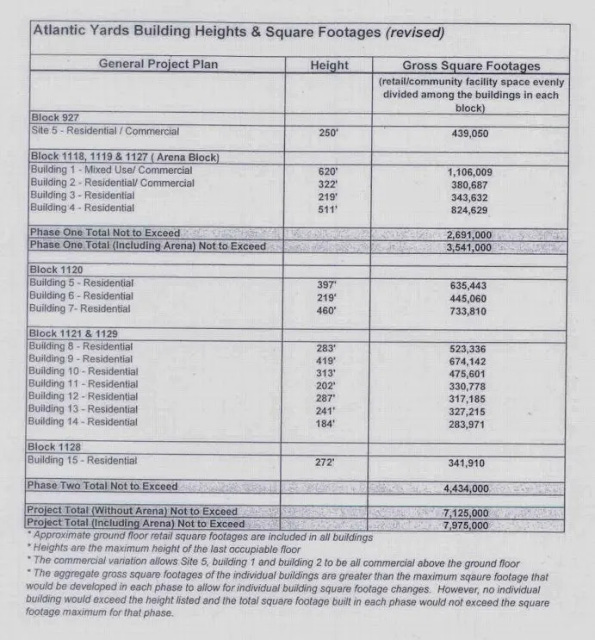

Still, both bids were well below the appraisal commissioned by the MTA: $214.5 million, which valued 3.6 million square feet of development rights at $75 per square foot, or $271 million, then subtracted costs for a relocated railyard, plus the platform. (The latter infrastructure costs, in retrospect, were a vast underestimate.)

Forest City claimed its bid, including a new railyard and subway entrance, was worth more, and the gubernatorially controlled MTA wanted an arena. Still, the MTA got Forest City to up its bid to $100 million cash.

Four years later, after the recession, Forest City renegotiated the payment terms: $20 million down for the arena parcel, then $8 million over four years; after that, starting in 2016, 15 installments of about $11 million each. Those payments—which result in the equivalent of $100 million, albeit at a gentle implied interest rate—were taken over by Greenland and now by Cirrus, after Greenland lost control in a foreclosure process.

My questions

I queried McDonnell during the meeting--he’s been friendly enough and somewhat responsive, if not exactly transparent, the two times I’ve queried him--about this issue.

How much of the new 1.6 million square feet of bulk, I asked, would be over the railyard? (The only alternative would be the Site 5 parcel, across from the arena, encompassing the approved bulk at Site 5 and also the B1 tower.)

“It depends,” he respond. The project is governed by “kind of one overall MGPP,” or Modified General Project Plan.

Yes, but the MGPP also set out maximum building heights and square footages.

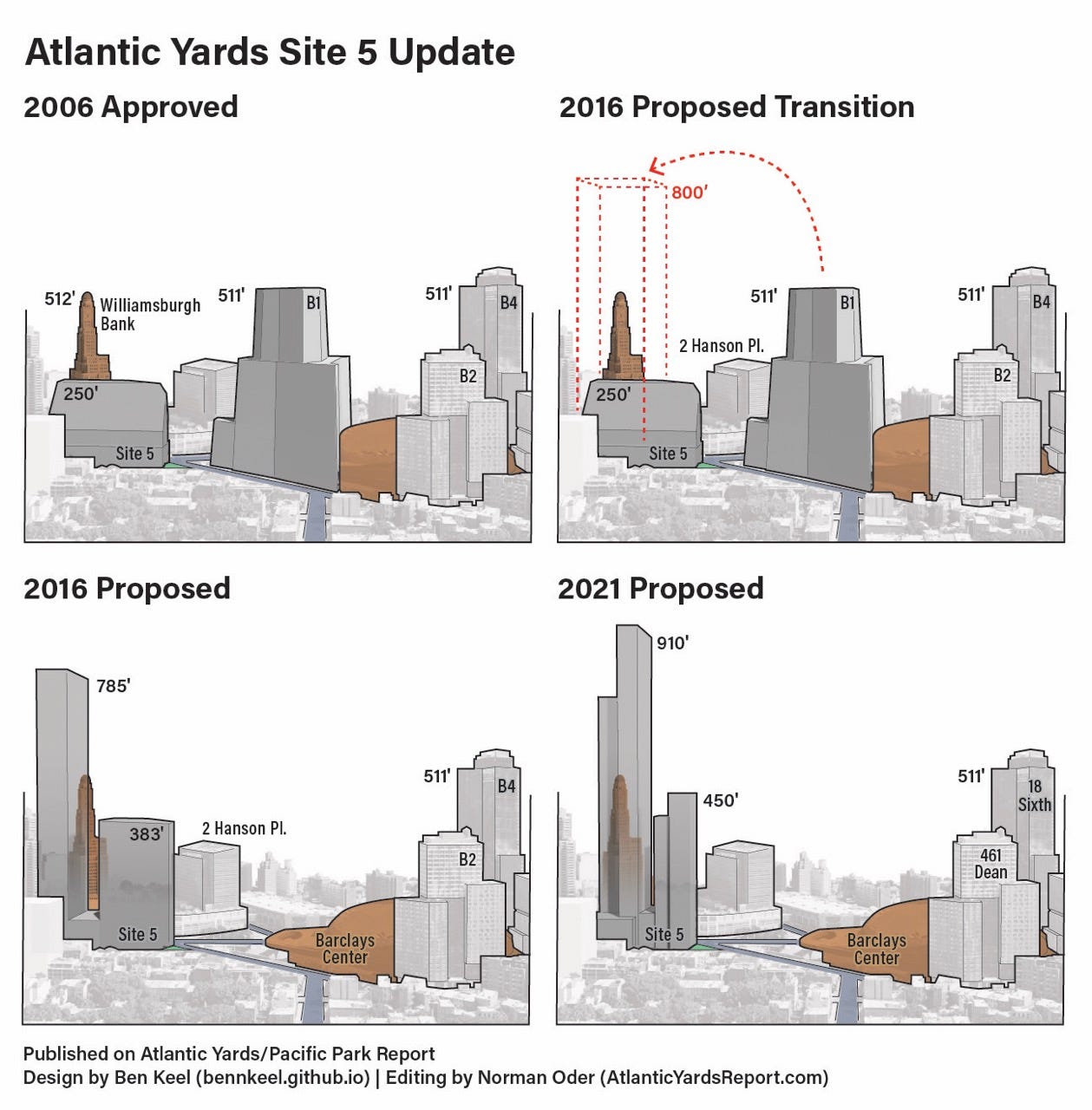

As of now, I’d bet all the new bulk would be over the railyard. After all, it seems unlikely they’d fully combine the approved bulk from B1 (1,106,009 square feet) and Site 5 (439,050 square feet) into a two-tower project with 1,545,059 square feet.

That’s because Exhibit K of a Site 5 Interim Lease, which ESD approved in October 2021 to advance development there, allows for up to 1,242,000 square feet at Site 5. That’s 303,059 square feet less, or 19.6%, than the combined total.

The graphic below is based on those 2021 plans. We now know the developers plan the taller Site 5 tower to rise 775 feet, and the shorter less at what seems to be at least 600 feet. (I expect to post a revision of the graphic.)

Paying the MTA?

“Are you,” I asked McDonnell, “expecting to have to pay for additional square footage over the railyard?”

“So we’re making the payments which are due to the MTA,” McDonnell replied.

“For what’s already been bid,” I said. “They bid for a certain amount of square footage, vertical square footage,”

“That’s not exactly how the parcel space purchase agreement works,” he responded. “They bid for the right to build on top, that’s subject to a Development Agreement and the MGPP.”

That suggests: if the Development Agreement changes, they can build bigger. “To rephrase it,” I asked, “are you expecting to pay for additional development rights?”

“We don’t know at this point,” McDonnell said, suggesting it would be an ESD and MTA decision. Those gubernatorially controlled bodies have not made any suggestion they’d require payment, and Cirrus, of course, was busy lobbying before it went public with its plans.

Looking more closely

I don’t have the purchase agreement McDonnell cited, but, assuming he’s right, we should understand the history.

Notably, MTA’s Request for Proposals discussed three parcels and assumed a certain level of bulk, a Floor Area Ratio (FAR) of 10. That translates, for example, to a ten-story building that covers the full lot, or a 40-story building that covers a quarter of the lot.

From the RFP:

MTA would consider a proposal that offers fair market value for land and/or air rights based on reasonable assumptions regarding rezoning or zoning override. Although the Site is currently zoned M1-1, it is contiguous to the recently expanded Downtown Brooklyn Special Purpose District, which provides for C6-4 zoning, allowing for an FAR of 10. MTA considers the assumption that the Site could be rezoned or could have the current zoning overridden to attain higher FAR reasonable.

The appraisal used similar assumptions. So it estimated 3,615,790 square feet of developable area over the railyard, or ten times the lot size.

Based on the maximum square footages document, I calculated that the six railyard sites that require a platform, B5 through B10, would total 3,487,392 square feet.

I estimated that 1.6 million additional square feet would represent a 31.8% increase over the project’s remaining approved bulk (including B1 and Site) or a 45.9% increase in the approved bulk over the railyard, to 5,087,392 square feet.

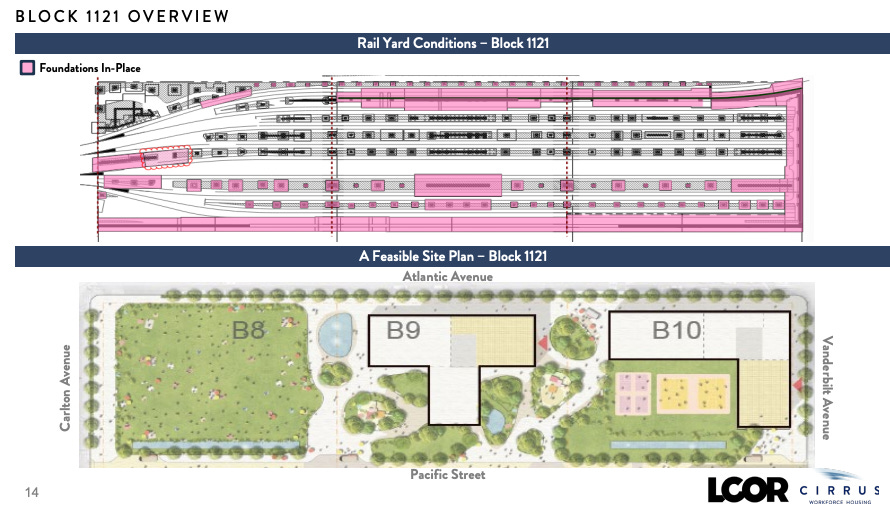

(Today, Cirrus/LCOR want to eliminate the B8 site, creating an additional acre of open space. They’d redistribute the B8 bulk to other towers and add more bulk.)

That amount of square footage approved for the railyard sites, as indicated in the document above, deserves two adjustments, which go in different directions.

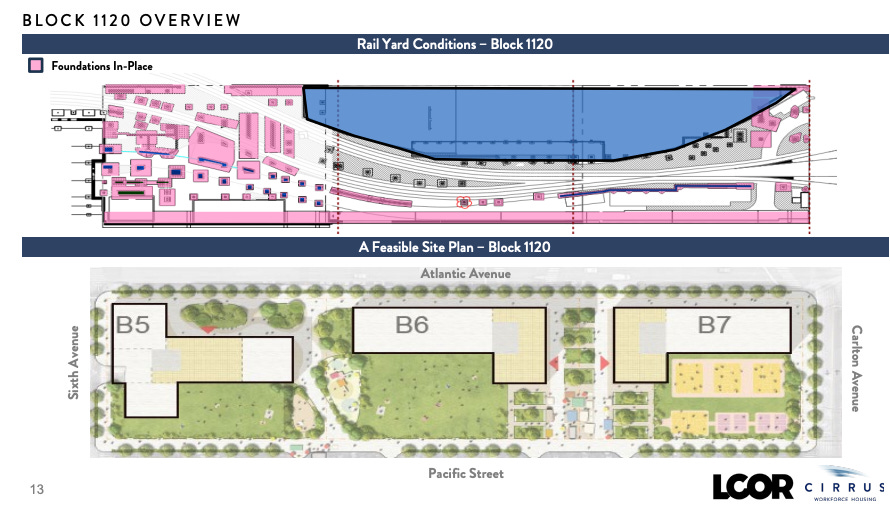

Here’s the first. Arguably, sites that require a platform should be able to support somewhat bigger buildings, because the square footage controlled by the MTA omits the terra firma segments, notably the “bump” below Atlantic Avenue between Sixth and Carlton avenue.

Add those parcels, with an FAR of 10, and the increase in square footage on Block 1120 might exceed 25%. (The developers will focus on terra firma, because it’s easier to build.)

The second adjustment, described at bottom, goes much farther in the opposite direction, suggesting that the original developers got significantly more square footage on the railyard sites than the RFP and appraisal contemplated.

How much should they pay?

Arguably, a 46% increase in railyard development rights should trigger a 46% increase in payments. If based on Forest City’s $100 million cash bid, they should increase to the present value of $146 million.

By that logic, shouldn’t the new developer pay the MTA the equivalent at least $46 million?

On the other hand, that might be a significant bargain. Even at $75/bsf, an additional 1.6 million square feet would be worth $120 million. At $200/bsf, that bulk would be worth $320 million.

What about infrastructure costs? As noted, the accepted $100 million bid was far lower than the $271 million appraisal, and even that gap couldn’t account for all the infrastructure.

But those costs were absorbed significantly by Forest City and Greenland. As McDonnell put it last month, “the largest subsidy provider to this project is no doubt Greenland. They put $950 million into the ground, and they also built a railyard.”

Cirrus and LCOR today can take advantage of that investment, lowering its infrastructure costs.

So why shouldn’t they pay $320 million? Or: should there be a new appraisal?

All this, of course, is political. ESD and MTA likely won’t push for payment unless the governor feels pressure.

A second, huge caveat

The second caveat that applied to the railyard development rights calculation seems huge to me.

Working on this article, I realized, for the first time, how the MGPP allows far more square footage over the three-block railyard than the RFP or appraisal contemplated. That made it a better deal for the developers.

(That’s putting aside, again, that the infrastructure costs turned out to torpedo Forest City and Greenland.)

Though the appraisal estimated 3,615,790 square feet of developable area over the railyard, or ten times the lot size, the railyard—even before any increase requested by Cirrus/LCOR—offered far more development opportunities.

Remember, it was a three-block railyard. The two blocks remaining have 3,487,392 square feet of development rights.

What about the other block, between Fifth and Sixth avenues?

It was used for (part of) the arena, and the B4 tower. The latter was allowed 824,629 square feet and built at 790,392 gross square feet. The arena is some 670,000 square feet. If 40% of that occupies the former railyard block, that’s 268,000 square feet.

Combined, that totals more than 1,058,000 square feet. The developers paid only $20 million for the parcel needed for the arena and, apparently, B4. Only later would payments unlock the parcels over the remaining railyard.

That looks, in retrospect, like a significant bargain, lowering land costs for the arena, now controlled by BSE Global, and for the B4 tower, built by Greenland USA and The Brodsky Organization.

As the mantra goes, the devil, as always, is in the details.

The waterfront in Williamsburg and Greenpoint also has absorbed large towers. The rezoning of Fourth Avenue, which runs south from Atlantic Avenue and essentially abuts the western end of Atlantic Yards, also has changed the scale nearby, but those towers are only 14 to 18 stories.

great article

We also need to add in the cost of ESD forgoing the penalties to the developer of $2000 a month for each unit of affordable housing that hasn't been built by June of this year according to the settlement with BrooklynSpeaks in 2014.

I think that adds up to another $168 million in subsidies LCOR and Cirrius is getting if the first unit of housig isnt built until 2030

I’m having difficulty understanding how this extra bulk could be assumed free while infrastructure costs such as water and sewage, traffic control, schools, taxi and bus demands/congestion all grow to a breaking point with the increase. Thanks for the analysis here!