In New York, Public Campaign Finance Has a Blind Spot

If city and state taxpayers fund candidates’ public relations efforts, shouldn’t we pay for some journalism?

OK, this policy essay is a little off-topic—though, arguably, our diminished press not only delivers un-vetted candidates but also leaves projects like Atlantic Yards under-scrutinized—but I couldn’t sell it as a freelance piece.

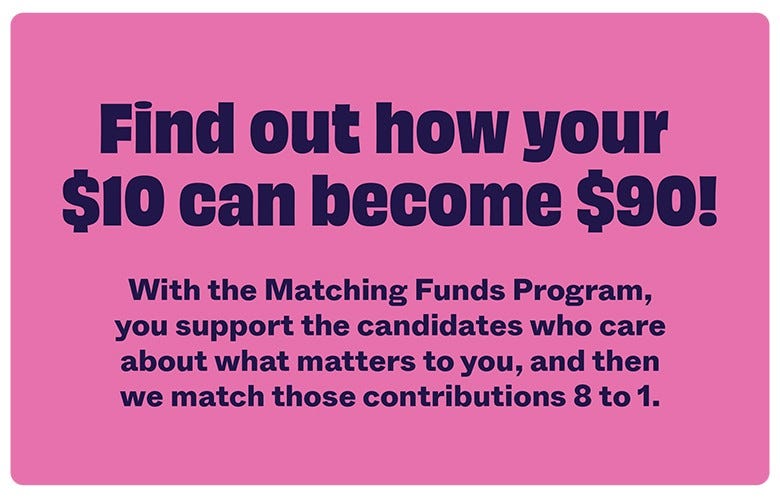

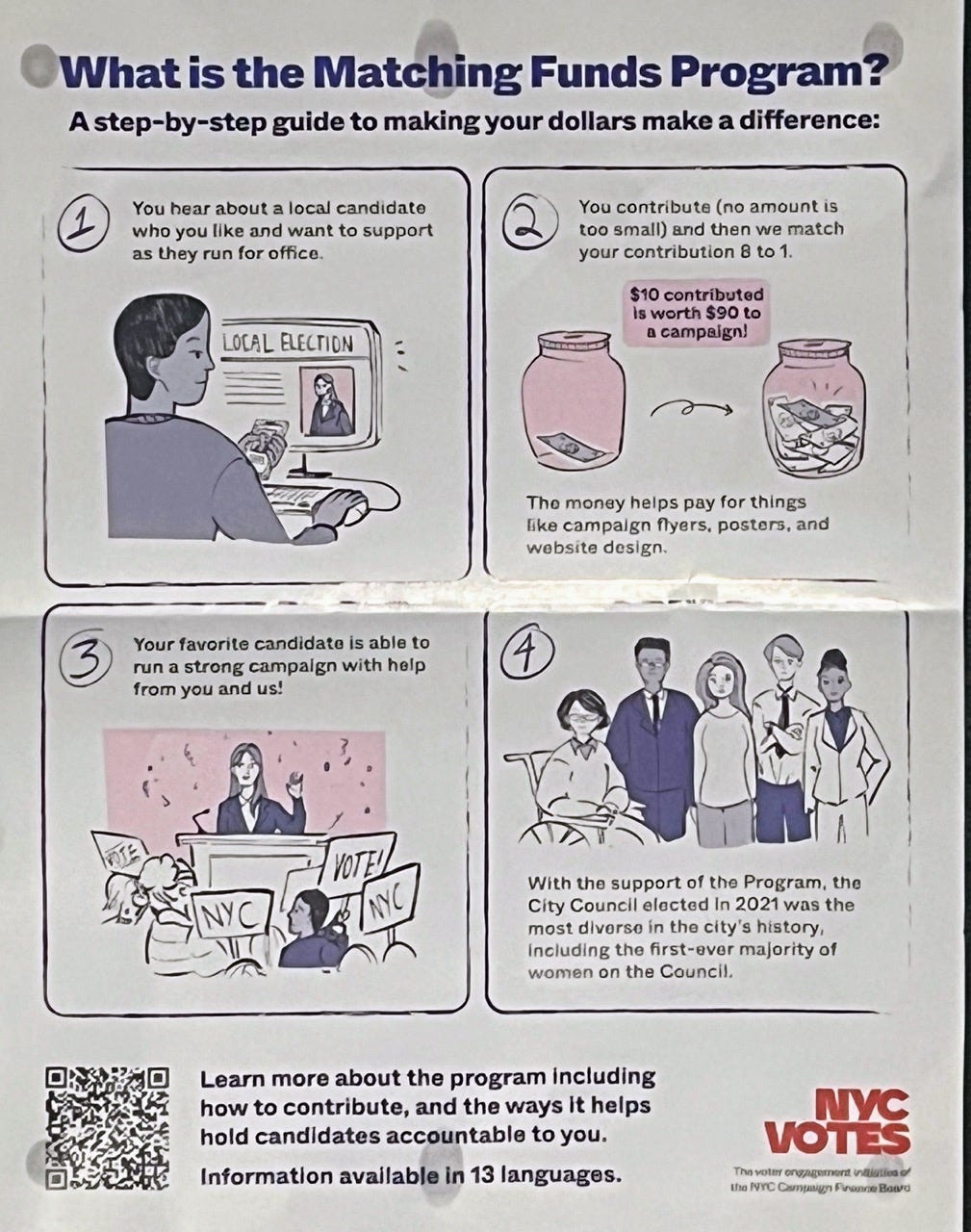

Since 1989, New York City has publicly funded citywide elections, as well as those for Borough President, and City Council. In 2019, that evolved to an 8-to-1 match for contributions up to $175, from local residents.

Yesterday, I got a mailer about it, from the New York City Campaign Finance Board (NYCCFB).

In 2010, NYU’s Brennan Center for Justice hailed the program, citing “more competition, more small donors, more impact from small contributions, more grass roots campaigning, and more citizen participation in campaigns,” while reducing the influence of big money.

For the 2021 election cycle, the NYCCFB paid out $127.1 million. Payments averaged $5.2 million for nine mayoral candidates, $2.4 million for eight Comptroller candidates, $717,458 for 27 Borough President candidates, and $153,982 for 264 City Council candidates.

How many of those candidates—and their taxpayer-fueled promotional spending—faced journalistic scrutiny or even in-depth interviews? Very few.

New York State in 2022 launched a similar program, matching local contributions of up to $250 on a 6-to-1 basis for statewide offices and up to 12-to-1 for state legislative offices. It cost $100 million in FY 2024 and is budgeted for $114.5 million in FY 2026.

That state program suffers, as The CITY and New York Focus reported last May, because, unlike with the city system, candidates face no cap on spending, and most campaigns will avoid being audited, which makes improper spending more likely.

The big flaw

Both laudable programs, though, share the same huge flaw. They foster an increasing imbalance between the amount of propaganda—campaign literature, mailings, advertising—delivered to voters and independent journalistic scrutiny of the candidates.

How many candidates, other than those running for mayor, face questions about their qualifications, background, and motivation for running? How many were profiled? How many candidate forums or campaign appearances were covered?

The answer, of course, is very few. That disserves the public. (How much scrutiny did a candidate for state Senate and Borough President named Eric Adams get?)

Such coverage is vital not just for the election at hand. It should help vet the candidates for the next round. Consider: some candidates likely don’t aim to oust an incumbent but rather to get name recognition–and thus a head start–on their next campaign.

For example, Brooklyn Borough President Antonio Reynoso is being challenged by Khari Edwards, who’s also gotten matching funds. Is Edwards likely to win? I doubt it. But he may try again. Both deserve vetting, as well as coverage of public events where they both appear. (I went to one.)

Another example: 35th District Council Member Crystal Hudson is being challenged by Dion Ashman, who’s also gotten matching funds. Yes, the incumbent is likely to win, but both deserve vetting even if—as far as I can tell—they’ve never appeared on stage together. (They should.)1

Setting the framework

If the public significantly funds the campaigns, shouldn't we support some vetting? Some fraction of public campaign funds, in both the state and the city, could and should go to journalism.

Consider: just 3% of spending—$3.8 million for 2021—could fuel a significant amount of valuable journalism.

Sure, it wouldn’t be simple. The money wouldn’t simply pay freelancers like me a decent wage. It also would have to support editors and, likely, new media outlets, as well as some oversight structure. That’s why this is a framework, not a blueprint.

Isn’t it risky for public entities to fund journalism? Yes, and the record is mixed.

How would recipients of such funding be chosen? It wouldn’t be simple and, yes, some might game the system, pursuing clearly partisan coverage.

Wouldn’t a state program be more complicated than a city one? Yes. (Let’s start with New York City.)

Would most or all the journalism funded be high-quality? Probably not.

Despite such caveats, we should acknowledge the problem and accept that public funding of campaigns should, reciprocally, fund journalism. Otherwise, campaign advertising and promotions might face no scrutiny.

(If you think I’m wrong, and/or this is too risky, please suggest another solution.)

This goal is far less fraught than funding overall local news coverage, a national challenge. In this case, the subject that merits coverage gets public money to influence public perception.

Baseline requirements

In fact, the city and state might mandate that any recipient of public funding answer a lengthy questionnaire about their qualifications, rationale for running, and campaign priorities, and how they differ from rivals.

Many do that anyway when seeking endorsements from political clubs and other organizations. Such questionnaires might be translated by AI—yikes!—into articles. But they could serve as a baseline for follow-up journalistic interviews, whether print, pixel, or podcast.

Otherwise, if we rely on the candidates’ self-serving websites, videos, and mailers, we might not learn enough.

We might even require candidates accepting public funds to participate in a minimum number of public appearances, interviews, or debates.

Local news under stress

Local news coverage, especially from daily and weekly newspapers, has been devastated by changes in business models, online classifieds, and competition from Google and Facebook, not to mention companies that soak, rather than invest in, the legacy publications they acquire.

In New York and elsewhere, efforts have surfaced to support local news, though none with as tight a nexus as helping cover publicly-financed elections.

Solutions from the nonpartisan consortium Rebuild Local News include tax credits for small businesses to advertise with local news outlets, fellowships for reporters, and direct grants from an independent nonprofit group. One guideline: “Be content-neutral, nonpartisan, and ensure editorial independence.”

The New York City Council in 2021 directed the city to devote half its advertising budget to ethnic and community media outlets, but, as HellGate recently reported, the Adams administration has fallen far short. The hyperlocal site Greenpointers reported resisting “subtle pressure” from the Mayor’s office to publish Adams’s op-eds.

Meanwhile, other publications that supply Adams a platform, such as Schneps Media and its amNewYork, have gotten far more support via this program.

Last year, the New York State Legislature passed the Newspaper and Broadcast Media Jobs Program (which began as the not-quite-the-same Local Journalism Sustainability Act), which offers $90 million in credits over three years to help local news outlets preserve—and, to a lesser extent, create—jobs.

That legislation has flaws and uncertainties, as noted by Dick Tofel in Vital City. Jeff Jarvis, former director of the Tow-Knight Center for Entrepreneurial Journalism at CUNY, blasted it for “excluding some broadcasters and the true future of news: digital and not-for-profit newsrooms.” (Rules have not yet emerged.)

It’s unlikely that such public support will translate into significant vetting of candidates, since much may simply sustain some legacy publications.

Campaign coverage

How to implement my conceptual framework? Well, no one’s addressed this specific funding issue, but rather the overall challenge of funding local news.

Economist Dean Baker, in The Nation, has proposed ”a coupon or tax credit so [people] can support the [local] news outlet of their choice,” not unlike the charitable contribution tax deduction:

There would be a similar determination in assessing eligibility for local journalism tax credits. A news outlet would merely have to show that it was engaged in the process of reporting local news. There would be no effort to determine whether it was doing a good job in reporting local news—that would be up to the individuals using their tax credits.

That draws on the Local Journalism Initiative outlined in Columbia Journalism Review by Robert McChesney and John Nichols. It could support analysts like Michael Lange, who writes the insightful Substack publication The Narrative Wars.

With city and state campaigns, New Yorkers could assign that tax credit to local media outlets, even short-term new ones, all—as Baker proposed—making such coverage available without a paywall. Alternatively, a grant program, as exemplified by the New Jersey Civic Information Consortium, might fund coverage.

Could new funding ensure an [Every Borough] Editorial Board, modeled on the volunteer, as of now, New York Editorial Board?

A small precedent has been established by the New York Editorial Board, a group of journalists who, after the New York Times abdicated its role in endorsements, has begun to interview mayoral hopefuls, “conducting and sharing editorial board-style interviews with candidates for high office and other civic leaders,” with transcripts on Substack.

But they’re volunteers. Could new funding ensure an [Every Borough] Editorial Board? Could college and graduate school journalism programs step up? Could podcasters and other new media? Let’s give it a try.

Looking at spending

Not only do candidates deserve questions about their biographies and their policies, their spending deserves scrutiny. Consider: last October, federal prosecutors charged Erlene King, the campaign treasurer for an obscure 2021 candidate for Brooklyn Borough President, with trying to steal matching funds.

Sure, maybe contemporary news coverage wouldn’t have revealed that King—as alleged—sent money to intermediaries for straw donor contributions to Anthony Jones’s campaign.

However, the outrageous numbers reported—a campaign that spent more than $812,000 while raising barely $83,000—should’ve drawn a spotlight. (It wouldn’t have escaped the old Village Voice muckrakers Wayne Barrett and Tom Robbins, aided by a cadre of interns, right?)

Similarly, it took until July 2022, after controversial “Bling Bishop” Lamor Whitehead was victimized in a livestreamed robbery, for the press to query him, without results, about an unexplained—and never repaid—$150,000 loan to his campaign to become Brooklyn Borough President. (He was later convicted of fraud in an unrelated matter.)\

Third-party spending by interest groups also deserves attention. Since the Independent Expenditures Portal already lists all the print and TV/radio/Internet advertising spurred by such spending, that should easily jump-start coverage. Would you believe that the group “Affordable New York” is… AirBnB?

Why it matters

It’s especially important to vet candidates, because public funds already support much “content” we see in local publications, notably news coverage generated by public relations specialists for government entities and elected officials. (As journalist Ross Barkan wrote in Columbia Journalism Review, the p.r. field “increasingly curates news for overworked, underpaid reporters.”)

Not just news, but opinion essays. Surely staffers write Mayor Eric Adams’ many op-eds in Schneps’ amNewYork. The Probation Department even hired an outside consultant to, among other things, prepare an op-ed.) Moreover, many nonprofit groups circulating press releases and opinion essays rely on government support.

We should do less to subsidize laundering of press releases and more to encourage civic journalism.

We’re in a strange moment. Some consider the media irredeemably biased. After all, President Donald Trump recently raved that the mere purchase of subscriptions by government agencies “COULD BE THE BIGGEST SCANDAL OF THEM ALL.” Trump now aims to axe all federal funding for NPR and PBS, which rely significantly, though not exclusively, on such funding.

But the basic work of journalism remains. Here in New York, the effort to bolster democracy has been admirable. However, public funding of candidates warrants public support for the fourth estate.

These are two campaigns that potentially intersect with my Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park coverage. All campaigns deserve attention.