Does the Barclays Center Offer Lessons for Philadelphia Arena Planners?

Yes, but the Community Impact Analysis relies on flawed articles and flattering photos. It omits the arena's expanded promotional canvas and the story of the green roof.

The contested proposal by the NBA’s Philadelphia 76ers to build a new downtown arena, dubbed for now 76Place, has Council Members and civic groups analyzing recent city-sponsored reports and considering competing plans.

Analyzing one of the four city-sponsored (but team-paid) studies, I found that ubiquitous consultant CSL International vastly distorted the New York arena concert market, thus arguing, simply, that more venues mean more shows.

Also flawed, from a Brooklyn perspective, is the Community Impact Analysis of the 76 Place Proposal, which focuses mainly on the project’s potential effect on Chinatown, the neighborhood very near the proposed arena site in Market East.

The arena, the report concludes, could “trigger a cascade of indirect impacts throughout the system, which could potentially result in the loss of Chinatown’s core identity and regional significance,” according to the cover letter from Martine DeCamp, Interim Executive Director of the Philadelphia City Planning Commission.

Barclays a benchmark?

According the cover letter, “The Consultant Team studied the community impacts of the construction and operation of” Barclays Center, Capital One Arena (Washington, DC), and Golden 1 Center (Sacramento) “for their comparable scale, location, and the availability of environmental review information.”

Was Barclays really a benchmark? Sort of, but, I explain below, the report got a lot wrong. (Coverage in the local press has been somewhat better but also flawed, as I’ll write separately.)

For Philly, the case study research was “inconclusive” as a guideline, given the venues’ different relationships to their neighbors, and the different planning processes behind them.

Indeed, while the Philadelphia site—largely replacing about one-third of a struggling mall, which the team owners would buy—may threaten Chinatown, construction would not directly displace any homes or businesses, as in Brooklyn.

The report relied on documents:

For each case study, the Team summarized the temporary and permanent impacts assessed by each project’s Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). Additionally, the Team spoke with planning professionals in each case study jurisdiction to understand their perspectives on the arena planning process and post-construction outcomes.

No planning professionals are named. It’s unclear whether and how much the “Team” examined—and assessed—not just the Atlantic Yards November 2006 Final EIS, but also the various subsequent documents, including the June 2009 Technical Memorandum, December 2010 Technical Analysis, and June 2014 Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement.

EIS flaws

Given the history of Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park, it’s risky to rely on an EIS that, for example, stated, “It is expected that the entire proposed development would occur by 2016.” That, of course, did not occur.

Then again, the author of the Atlantic Yards EIS was the ubiquitous consultant AKRF and—guess what!—AKRF is a contributor to the new study, which states:

The EISs of the case studies generally found that the arenas would be compatible with their development areas and help to achieve the desired buildout in revitalization districts by providing direct investment and physical improvements in an accelerated time frame… The benchmark EISs did not treat the impact on existing retail as a fatal flaw in any of the projects.

In other words, the threat to Philadelphia’s Chinatown, with a fine-grained retail environment, is not what other cities faced.

What the EIS omitted

Unmentioned: the lesson from Barclays Center is that the EIS is neither foolproof nor comprehensive. As mentioned, the EIS vastly miscalculated the timing of the project.

The EIS assumed a giant office tower—B1, dubbed “Miss Brooklyn” by original architect Frank Gehry—looming over the arena, with an atrium, or Urban Room. That never got built.

The EIS assumed a Gehry-designed 850,000 square foot arena, big enough to host NHL hockey. Instead, the recession caused original developer Forest City Ratner to downsize to a 675,000 square foot arena, from Ellerbe Becket, too small for major-league hockey, as the New York Islanders discovered, to their dismay.

After an outcry, Ellerbe Becket’s design was later revised by SHoP, delivering not an Urban Room but a plaza that turned out to be crucial to arena operations and branding. The plaza included an oculus—an oval prow with an interior wraparound screen for digital advertising—that was never evaluated.

Moreover, after Joe Tsai in 2019 took over the Brooklyn Nets and the Barclays Center operating company, he added another layer of digital advertising—an LED “wall” over the entrance doors—and used the plaza’s entrance to the transit hub as another vehicle for advertising.

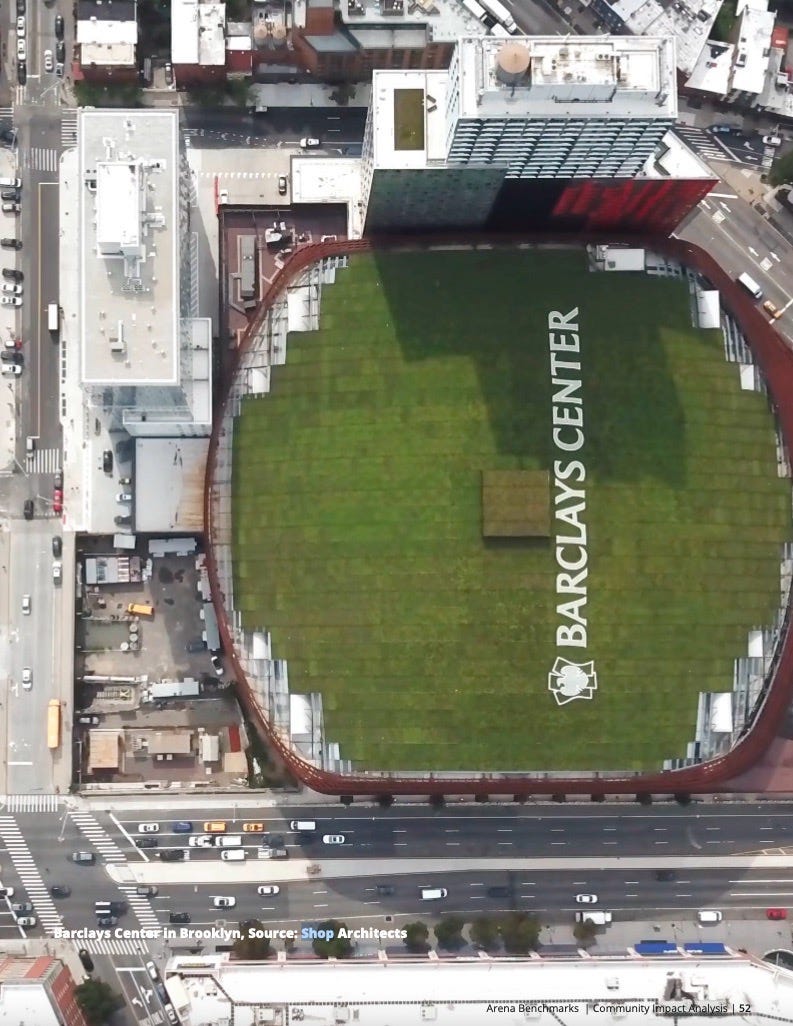

In other words, arena operators will try to monetize the maximum amount of exterior space. That’s not visible in the photo below, a flattering image supplied by SHoP Architects for the Philadelphia study.

Also not visible: the advertising that wraps around the entrance to the transit hub. Tsai later added a neon art installation that, I’ve argued, doubles as advertising.

The EIS assumed that the arena would be flanked by retail. In reality, the retail outlets on Atlantic Avenue were a bust, while the ones along Flatbush Avenue were only intermittently occupied, until the team store expanded to take over the entire flank.

The EIS assumed there would be significant traffic from New Jersey-based fans of the Nets who would travel to watch “their” team. Instead, the Nets’ long goodbye from New Jersey alienated locals, while the Brooklyn Nets reconstituted their fan base locally.

Changes, changes

From the report:

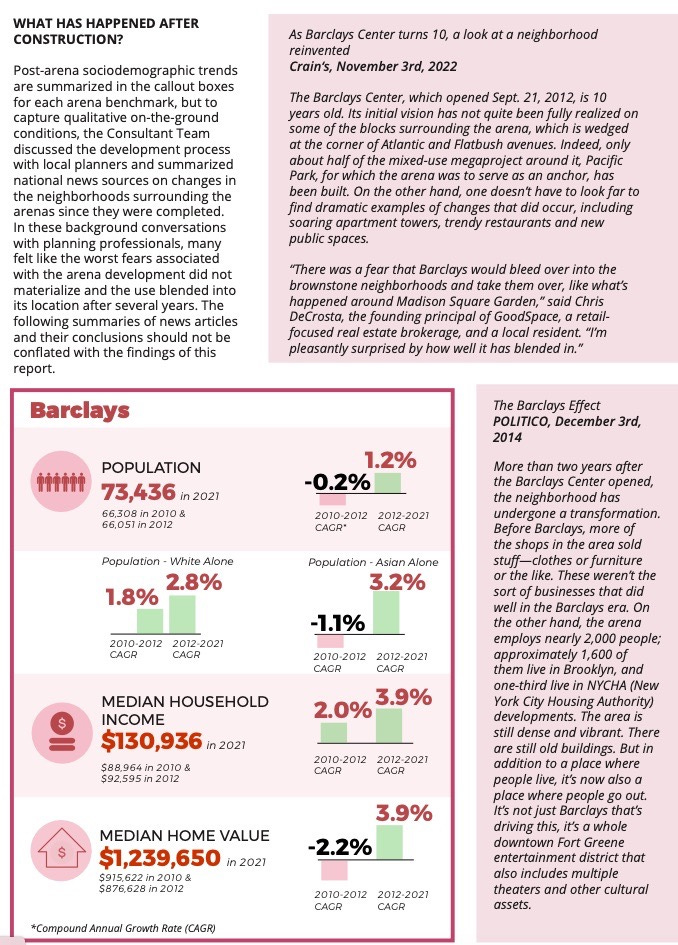

Each of these benchmarks’ study areas experienced increased population growth in the neighborhoods surrounding the arenas in the time period after the arena was built. In terms of minority population changes, in Brooklyn, the non-white population was declining in the two years prior to the arena being built, and declined at a less rapid pace after it opened. In the years preceding the construction of the Barclays Center, the surrounding Brooklyn community was already experiencing extensive changes; the 2004 rezoning of Downtown Brooklyn, located just north of the Barclays study area, led to substantial residential property development and the construction of approximately 14,000 new housing units in the area, contributing markedly to demographic shifts in the community.

Yes, the surrounding area was already experiencing extensive changes.

What goes unmentioned is that Atlantic Yards, announced at about the same time the Downtown Brooklyn rezoning was launched, was supposed to stem the tide of gentrification by delivering 2,250 affordable housing units, among other promises in the much-hyped Atlantic Yards Community Benefits Agreement (CBA).

Also unmentioned: the 1,374 below-market apartments built so far have skewed toward middle-income households, with low-income units lagging behind the percentage promised in the CBA. Moreover, delays mean that affordability is calculated from an ever-expanding base.

I’m not sure the trends summarized in the box below are terribly meaningful, since they focus—perhaps because of the Philadelphia concerns?—on white and Asian populations, rather than, as was key here in Brooklyn, the diminishing Black population.

The trends regarding Brooklyn’s household income and home values, the study acknowledges, may be difficult to attribute to the arena or rather larger forces.

Post-construction impacts

In “background conversations with planning professionals, many felt like the worst fears associated with the arena development did not materialize and the use blended into its location after several years,” the study says.

That’s not untrue, especially since the New Jersey fans did not materialize, but it ignores the significant, if intermittent, impact of certain Barclays Center shows, attracting families and seniors, that draw a lot of vehicles either idling, seeking free parking, or waiting for pick-ups.

Or, for example, a flood of buses inundating nearby streets.

“The following summaries of news articles and their conclusions should not be conflated with the findings of this report,” the document says, though the two articles chosen cheerlead for the arena.

In Crain’s

The study excerpts a Nov. 3, 2022 article from Crain’s New York Business, "As Barclays Center turns 10, a look at a neighborhood reinvented:

The Barclays Center, which opened Sept. 21, 2012, is 10 years old. Its initial vision has not quite been fully realized on some of the blocks surrounding the arena, which is wedged at the corner of Atlantic and Flatbush avenues. Indeed, only about half of the mixed-use megaproject around it, Pacific Park, for which the arena was to serve as an anchor, has been built. On the other hand, one doesn’t have to look far to find dramatic examples of changes that did occur, including soaring apartment towers, trendy restaurants and new public spaces.

“There was a fear that Barclays would bleed over into the brownstone neighborhoods and take them over, like what’s happened around Madison Square Garden,” said Chris DeCrosta, the founding principal of GoodSpace, a retail-focused real estate brokerage, and a local resident. “I’m pleasantly surprised by how well it has blended in.”

As I wrote in my critique, given that Crain's is a business publication, it's not surprising that the coverage, though not fully rah-rah, would tilt positive and ignore some pesky issues.

The changes nearby were unlocked most significantly not by the arena but by the Downtown Brooklyn rezoning. While the proximity to the arena certainly didn't deter construction, which some might have feared, I don't think it's mainly responsible for inducing it, though it surely had a larger effect on hotels.

The most consequential part of the Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park buildout--the two-block platform over the MTA's Vanderbilt Yard, the six large towers planned, and the majority of the open space--still awaited, as I wrote. Still do.

Had the arena helped--or, at least, not hindered--real estate development nearby? Had it helped some retail outlets, notably those offering food and beverages? Yes on both, though neither trend was simple, or uniform.

As to whether the “vision has not quite been fully realized,” well, that’s an understatement. Though about half the approved units have been built, the project is not half-finished, given the need to deck the railyard and build six towers--plus, of course, Site 5, catercorner to the arena block and longtime home to two big-box stores, P.C. Richard and (now closed) Modell's.

The article suggested that the arena’s “most unexpected legacy” was the plaza, a public space that, during 2020 protests, was "totally appropriated," according to one organizer, to become what I called “Brooklyn’s accidental town square.”

Again, that’s a sign that the EIS may not be a good predictor.

In Politico

The other article excerpted is from Politico (originally Capital New York), Dec. 3, 2014, headlined The Barclays Effect:

More than two years after the Barclays Center opened, the neighborhood has undergone a transformation. Before Barclays, more of the shops in the area sold stuff—clothes or furniture or the like. These weren’t the sort of businesses that did well in the Barclays era. On the other hand, the arena employs nearly 2,000 people; approximately 1,600 of them live in Brooklyn, and one-third live in NYCHA (New York City Housing Authority) developments. The area is still dense and vibrant. There are still old buildings. But in addition to a place where people live, it’s now also a place where people go out. It’s not just Barclays that’s driving this, it’s a whole downtown Fort Greene entertainment district that also includes multiple theaters and other cultural assets.

Yes, there are a lot more consumption-oriented retail outlets, but, as I wrote in my critique, an article relying on a Barclays Center rep, the Brooklyn Chamber's head, and a happy bar owner, counterposed by a couple of one-step-removed academics, is bound to miss a few things.

Also, there’s a variability to the "Barclays effect," which applies mostly to bars and restaurants, and more significantly to one-off events like concerts, rather than basketball games. Early on, in fact, Barclays offered a good deal on food and drink for higher-priced tickets that many people stayed inside the building.

The arena jobs? They’re part-time, usually without benefits.

More on impacts

From the report, regarding Atlantic Yards/Barclays Center:

Overall, the traffic, parking, and street closure impacts were significant, with the largest impacts anticipated to occur during pre-game and post-game hours. Mitigation measures included signal changes and street widening. The EIS found that other intersections that could not be mitigated would not be frequently impacted. Eight acres of open space, a bicycle path, and other community uses were anticipated for the entire master plan area. The open space was to account for over 35 percent of the entire project site and enhance pedestrian circulation and promote public access to and use of the entire site.

How can the failure to deliver five-acres of the eight-acre open space on the promised timeline be ignored?

Missing context

Notably, the second and final photo of the Barclays Center (below), supplied by SHoP, offers even less context than the first one, and omits key information.

The empty lot at lower left is now occupied by 18 Sixth Ave. (B4, aka Brooklyn Crossing), the largest tower in the project so far, rising 511 feet and containing some 824,000 square feet. It’s far larger than the other two towers visible.

Also, a slightly wider shot would show, just west of Sixth Avenue, the more recently built 662 Pacific St. tower (B15, aka Plank Road), flanked by lower-rise buildings that show a shifting scale in the neighborhood.

What about the green roof?

Notably, the provision of a green roof, with the Barclays Center logo, deserves explication. In the arena’s initial iteration, the rubber roof also boasted a Barclays Center logo, also never disclosed nor discussed.

Lesson: the arena operator will not miss an opportunity to use building’s exterior for promotion.

More importantly, the green roof saga also shows the limits of relying on an EIS and failing to do a full review. A publicly accessible green roof was initially promised, then dropped for the more cost-effective rubber roof.

Shortly after the Barclays Center opened, neighbors were alarmed when they could feel pounding bass from certain concerts inside their homes.

The green roof was restored as a purported visual amenity, but the main goal, which was achieved, was to tamp down that bass, as I wrote. Also, a construction accident killed a worker. That wasn’t “anticipated,” either.

About planning

Interestingly enough, the report found that the Brooklyn and Washington arenas “fit into a larger master or general project planning process that brought together public and private entities and offered multiple opportunities for public participation.”

That fails to explain how Atlantic Yards was driven by the governor, limiting local political clout.

Yes, public comment and feedback generated marginal changes—and other promises, like a transit pass connected to Nets tickets, fell by the wayside—but the developer and state were in control.

For some reason, the report fails to mention how the project provoked several lawsuits challenging the use of eminent domain, the adequacy of the environmental review, and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s willingness to renegotiate the deal for railyard air rights.

What about the CBA?

From the document, regarding the planning process for the benchmark arenas:

It also resulted in the negotiation of community benefits agreements [CBAs] that included grants for businesses during construction, tickets and free/discounted event space for area residents and school-children, increased park or open space, and other benefits.

It’s unclear how much of that sentence is attributed to Brooklyn, where free tickets have been distributed but low-cost usage of the arena was promised but not delivered. More important aspects of the Atlantic Yards CBA, like low-cost housing, job training, and minority hiring/contracting, either evaporated or are well behind predictions (and not monitored).

Also important: the Atlantic Yards CBA resulted not from any public process but rather a private contract that was not subject, as with some other cities’ CBAs, to monitoring by public bodies.

The bottom line

The analysis notes that there’s no required local or state environmental review process in Philadelphia, so the studies commissioned help compensate for that.

The Philadelphia process is a city approval, steered by the local Councilmember, not, as with Atlantic Yards, a state process. Philly Councilmember Mark Squilla has been holding his cards close to his vest, which sounds—I speculate—that he’d like to craft a compromise.

From what I can tell, the document offers an in-depth and nuanced analysis of the potential impacts on Philly’s Chinatown. It does not, however, offer a thorough or thoughtful analysis of the Barclays Center or the related Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park project.