Making Sense of the 962 Pacific Street Rezoning Story

The New York Times wrongly posited a NIMBY backlash, missing the Community Board's affordability gain, and downplayed reasons for skepticism. But yes, it was Council Member Hudson's call.

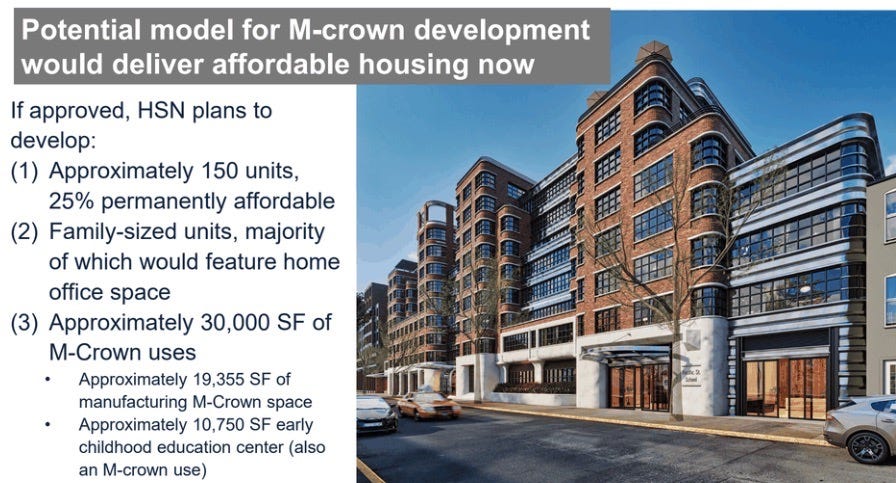

Why should I write about a New York Times series on the “affordability crisis,” which included two articles chronicling 962 Pacific Street, an empty lot that might have delivered a new 150-unit building with affordable housing in Crown Heights?

Because 1) yes, it’s Atlantic Yards-adjacent, in a few ways; 2) the Times got some key things wrong; and 3) such coverage furthers the simple “build more homes” narrative. As the only reporter to steadily cover 962 Pacific, I know the story of this failed rezoning is far more complicated—and strange—than presented.

Notably, Brooklyn Community Board 8 didn’t offer knee-jerk opposition, but successfully negotiated more affordable housing than landowner Nadine Oelsner initially proposed and some CB 8 leaders, as well as Oelsner’s nonprofit housing partner, were willing to accept.

That commitment might have poised the project for passage. Community Boards, however, have only an advisory role in the city’s Uniform Land Use Review Procedure, or ULURP, which was required in this case because of the need to transform outdated industrial zoning.

Then Council Member Crystal Hudson, who might have tried to wrangle a better deal from a developer gaining a lucrative opportunity, said the project still crossed her red line.

The key articles were Two Apartment Buildings Were Planned. Only One Went Up, published Nov. 19, and Brooklyn Needs Housing. She Has a Vacant Lot. Why Can’t She Build?, published Nov. 21.

What was missing

After the series came the self-serving article, A Housing Crisis Deepens, and a Reporter Digs In, that appeared Nov. 27 on the “Inside the Times” page.

Reporter Mihir Zaveri, who covers housing around New York City, had responded to his editor’s call to “find a way to portray New York City’s housing crisis in a really granular fashion, explaining with as much detail as possible what stands in the way of solving it.”

But a lot was missed. Otherwise, the Times would not have portrayed Oelsner’s team as white knights, as opposed to savvy negotiators, sometimes evasive, misleading, or crying wolf.

However professedly community-minded, they understandably were aiming for a big payday, pursuing a high-risk, high-reward game, borrowing millions of dollars to rezone a parcel, acquired for just $1,000 in 1974, worth perhaps around $20 million today.

Nor would the Times have written that CB 8, which gave the 962 Pacific development team many opportunities to tweak its project, “recommended that the project be rejected, unless Oelsner made more apartments cheaper and was more transparent about her potential profit.”

It wasn’t that simple.

Oelsner’s team offered 25% affordable housing. After CB 8’s Land Use Committee sought 35%, expanding the number of lowest-income units, and the developer agreed to 32%, the full Board endorsed that revision.

Yes, technically, the resolution, summarized above, was to withhold support unless certain conditions were met, but the applicant had essentially agreed to meet them, promising 27 apartments at 40% of AMI, 5 at 60% of AMI, and 16 at 80% of AMI.

At the subsequent City Planning Commission hearing, when a Commissioner noted the seeming disapproval, the applicant’s attorney, Richard Lobel responded, “As a technical matter, the vote was a ‘deny unless,’ which is something that Community Board has used before on prior applications,” preceding resolution at City Council.

Project partner Michelle de la Uz of the nonprofit Fifth Avenue Committee confirmed Oelsner’s assent at a subsequent City Council subcommittee meeting.

As to financial transparency, there were no contingencies.

Moreover, the Brooklyn Borough President backed the project, in an advisory vote, and the City Planning Commission, with just one dissenter, approved it.

So there might have been, among those 27 lowest-income apartments, studios at $1,087, one-bedrooms at $1,165, two-bedrooms at $1,398, and three-bedrooms at $1,615.

Hudson’s call

This Times passage got to a key issue:

Hudson had said she would not support individual developments until the broader neighborhood rezoning was finished. When she voted against Oelsner’s proposal at a Council meeting earlier this year, she said the lot owner was essentially trying to cut in line.

Which she may have been.

Or was it more like proceeding through an intersection after the traffic light has been stuck on red for what feels like too long?

Well, Oelsner was trying to cut in line.

Had the light been stuck on red? Not quite. After all, Hudson and her predecessor, as well as those in adjacent districts, had already green-lit several spot rezonings nearby.

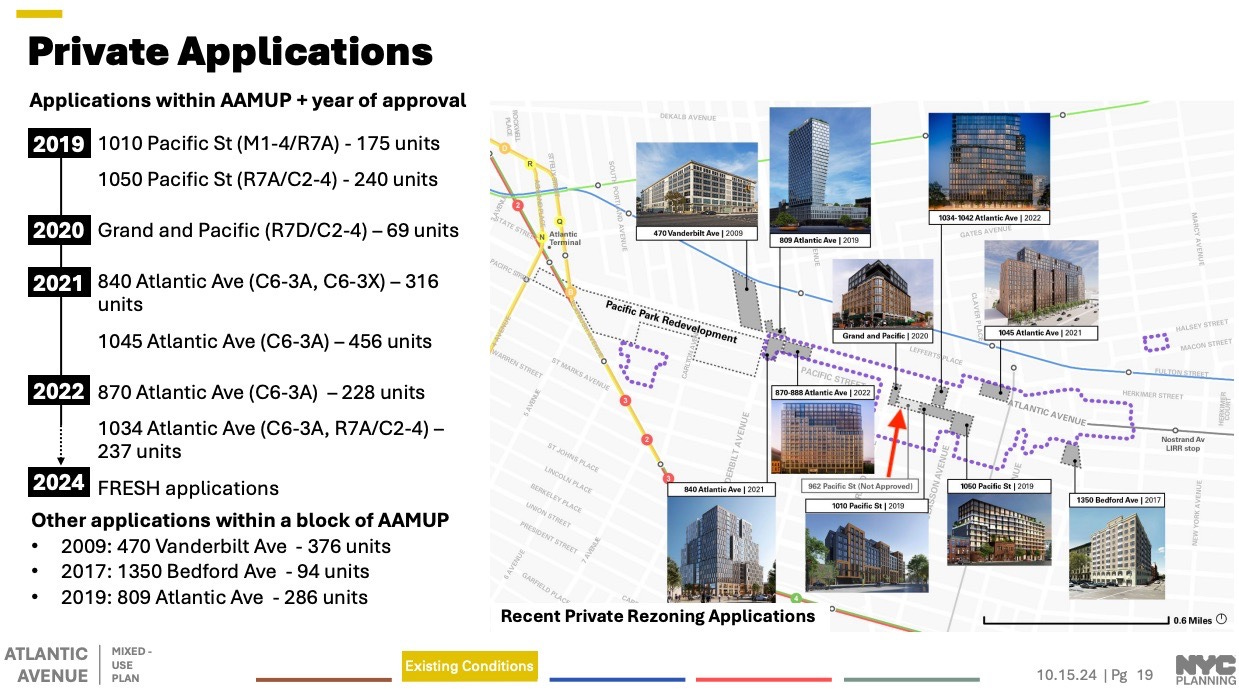

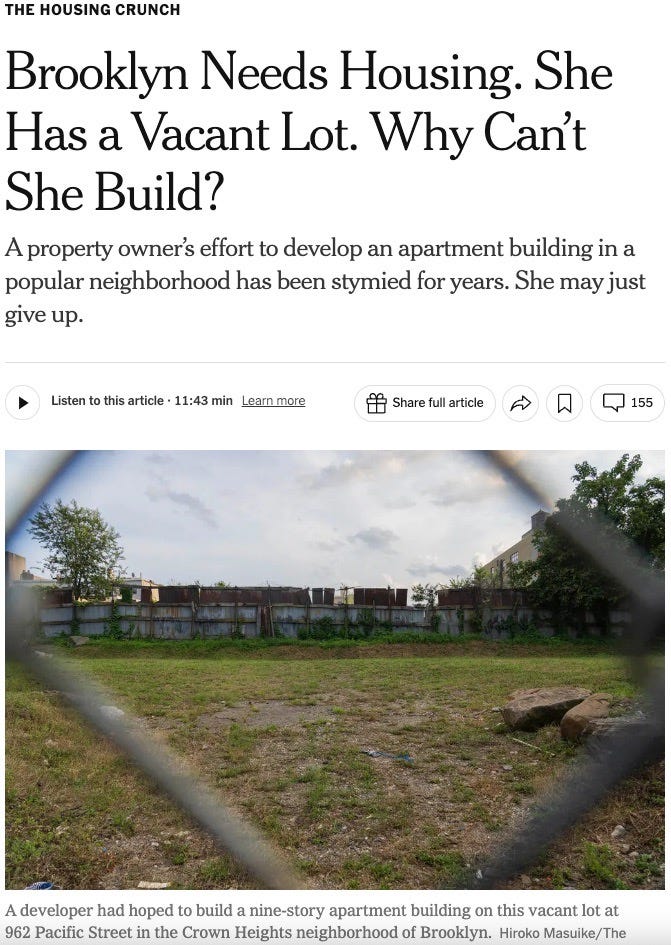

See the map below, from a Department of City Planning presentation on the pending Atlantic Avenue Mixed-Use Plan (AAMUP), an area involving 21 full or partial blocks mostly east of Vanderbilt Avenue (and Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park), stretching from Prospect Heights into Crown Heights and Bedford-Stuyvesant.

So, it was more like an irregular traffic light that occasionally turned green after significant lobbying.

Was it arbitrary to oppose this one? Maybe, maybe not.

962 Pacific backers noted that nearby parcels had gotten spot rezonings, so this would harmonize zoning on the block. See screenshot below. One counterargument: some had been bad deals for the public.

Hudson made it clear from the start that she would not consider more private rezonings, after approving ones that had started ULURP before her tenure. She spoke similarly at the hearing when she voted it down.

Oelsner argued they begun their plans at a reasonable time, after Borough President Eric Adams, Hudson’s predecessor Laurie Cumbo, and the CB 8 Chair in August 2018 signed a letter seeking an area rezoning.

That was before Hudson took office and, of course, before the pandemic delayed government processes. So bad luck was a key factor.

Not a NIMBY issue

Hudson was not echoing NIMBYs, because Community Board 8 leaders, as well as established nonprofit organizations, had long supported the project, and the full CB 8 eventually did.

Oelsner had contracted with the Fifth Avenue Committee, a nonprofit housing group, which supported this project and had been part of other nearby rezonings, 870-888 Atlantic Ave. and 1034-1042 Atlantic Ave., that Hudson negotiated at the last minute.

The Fifth Avenue Committee, whether out of strategy or partnership, had already blessed the 25% affordability plan, while CB 8’s Land Use Committee pushed for more.

Oelsner’s HSN Realty also allied with Evergreen Exchange, a nonprofit advocate for industrial firms, to find 962 Pacific commercial tenants, fulfilling Community Board 8’s call, via its proposed (but not passed) M-CROWN rezoning initiative, to retain good-paying jobs.

A better result?

Gib Veconi, the head of CB 8’s M-CROWN subcommittee and a key member of the Community Board, responded on X/Twitter to the first Times article that the deal Oelsner agreed to, in terms of affordability, was better than what Hudson could get from the pending neighborhood rezoning, the Atlantic Avenue Mixed-Use Plan.

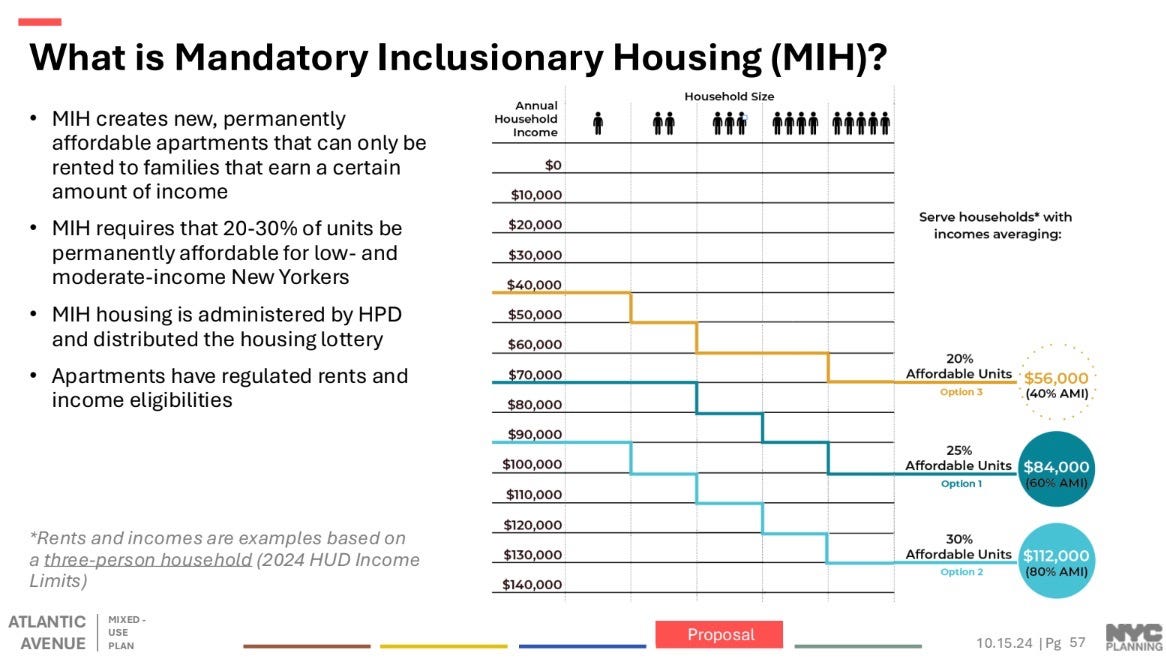

Indeed, that seems likely, at least if Oelsner were held to the deal promised CB 8, not the configuration described in the Times. She had committed to more, in terms of unit count and affordability level, than what’s available under the city’s Mandatory Inclusionary Housing (MIH) policy.

Veconi commented on the first Times article that “it simply takes too long (10 years in CB8's case) for the Department of City Planning to create a neighborhood plan to address rising housing costs due to gentrification,” since Area Median Income (AMI)—the basis for calculating affordability—continues to rise.

“This,” he added, “is why private rezonings like 962 Pacific Street need to be an option, especially when a community has already laid out a clear vision for developers to follow.”

Still, Veconi’s statement that “[t]here would have been no public subsidy of 962 Pacific's affordable units” refers to direct cash, which was offered for the counter-example in the article, an Upper West Side project. As the Times acknowledged, a property tax exemption would be a subsidy.

Moreover, while an upzoning doesn’t involve cash, it should be seen as significant public assistance and thus worthy of reciprocity, especially when it allows a developer to get ahead of the competition from an area rezoning.

Remember how architect/planner Vishaan Chakrabarti once said: “Look, there's only two legal ways to create money in the United States, the Federal Reserve and an upzoning. So free FAR [Floor Area Ratio] is worth its weight in gold.”

No deal this time

Given the recent history, and the fact that Oelsner had already agreed to more affordability than likely would be required under the AAMUP, I had suspected Hudson would negotiate a last-minute improvement in Oelsner’s plan.

After all, there’s usually slack in a developer’s offer.

Meanwhile, Oelsner would’ve gained not just the opportunity to build market-rate units before the area rezoning enabled a potential glut, but also to build on a block where much construction had already been completed, minimizing disruption to new tenants.

Instead, Hudson held her ground, which I suggested might be some “clout-claiming”—essentially saying, When I said no more one-off projects, I meant it.

Yes, a comprehensive plan could deliver other neighborhood assets like open space and streetscape improvements. But that didn’t stop previous applicants.

Asking for more?

Perhaps the development team had pissed Hudson off, since they ignored her clearly stated stance when she entered office.

Or maybe she asked for more but hit a wall.

Remember, the real estate publication The Real Deal reported, with dubious sourcing:

Hudson reached out to Oelsner through an intermediary and offered to bless the rezoning if the developer would build 100 percent affordable senior housing at another site, a source close to the developer said. She also asked for $5 million to $10 million to be placed in a fund for affordable housing that would be managed by a third party, the source said.

…Hudson’s office responded to a request for comment three weeks later, calling the alleged offer “categorically false.”

Did something like that happen? Who knows, but it’s plausible that some negotiations occurred. (The Times didn’t ask.)

After all, elected officials like "100% affordable housing. Two such sites on Dean Street and Bergen Street, outside the AAMUP rezoning area and in process before the study began, have been added to the plan, apparently to both accelerate their zoning change and to give elected officials credit for delivering deeper affordability.

The valuable upside

One message from the Times series might be: We need more housing, so we should let landowners and developers build more.

Most Times commenters condemned Hudson as blocking progress. The indie news site HellGate snarked, “Another reminder that it's too fucking hard to build new housing in New York City.”

Complicating that: a spot rezoning can be enormously lucrative, and deserves reciprocity, as well as policies—see the Pratt Center—that allow the city to capture the upside from property flippers.

The Times’s coverage did acknowledge that the privately owned site “made the project potentially very lucrative for the owners, even if it added some benefit to the community.”

Missing, however, was the stark record nearby.

Consider 1010 Pacific Street, the parcel directly east of 962 Pacific. Promises of historic architecture, a community center, and deeper affordability fell by the wayside, because the overambitious plans were downsized and purported commitments weren't locked down.

The rezoning applicant flipped the real estate soon after the project was approved in 2019, selling parcels that cost $8.5 million for $20.25 million. (That’s not the only cost. The Citizens Budget Commission two years ago estimated it costs $2 million to rezone for a mid-rise building, plus potential financing costs for the land.)

The final land cost for 1050 Pacific, a larger spot rezoning just past Classon Avenue, was $48 million. Yes, neither building had the same affordability requirements that Oelsner seemed willing to affirm, but the 962 Pacific site could be worth $18-$20+ million, based on rough comparables.

Another example, not previously reported: the team behind 1057 Atlantic Avenue (formerly 1045 Atlantic Avenue), a spot rezoning that yielded a large, 456-unit building in Bedford-Stuyvesant, sold the project for $65 million after rezoning parcels that cost of $24.9 million. (See more below.)

That project, about six minutes by foot north and east of 962 Pacific, is about three times the bulk of Oelsner’s proposal.

Oelsner’s numbers

Oelsner’s family had owned 962 Pacific for decades. In 1974, they paid the minimum bid, $1,000, at auction, to buy the property from the city. She took out loans to relocate the lot’s commercial tenant, clean up the parcel, and hire the consultants—legal, environmental, and more—to get the rezoning passed.

(Here’s the project’s lengthy Environmental Assessment Statement, or EAS, which, for example, concludes that “the Proposed Development would not result in a parking significant shortfall.”)

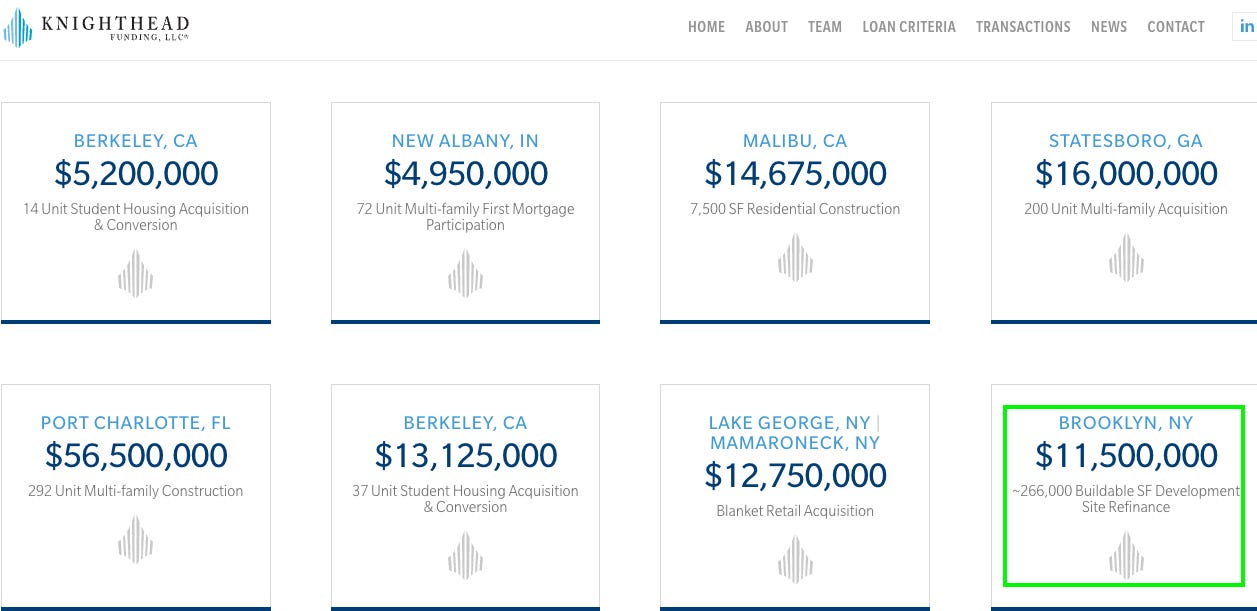

The $11.5 million loan package--including an additional $3 million in October 2023--came from a non-bank source with presumably high interest rates.

Documents memorializing the additional $3 million showed the inclusion of not just 962 Pacific but a separate HSN-owned parcel at 975 Atlantic Avenue, home to AutoZone Auto Parts—another prime development site and, apparently, additional collateral to stretch the loan.

Does that mean they might lose the 962 Pacific site, as Oelsner’s team repeatedly warned? Or does that mean they’d earn less? Unclear.

One CB 8 member asked Oelsner, “What is the projected sort of margin that you are expecting to have on this project?”

“Let’s come back to the Community Board,” she replied, but ultimate response was evasive.

Was the question invasive? Well, it was relevant, given claims that they were being squeezed.

Generous framing

The Times offered generous framing to support its thesis:

But at the corner of Grand Avenue and Pacific Street, a 33,000-square-foot lot has been vacant for more than 50 years.

That’s inaccurate. First, the parcel is midblock.

More importantly, while it has lacked buildings for more than 50 years, the site did accommodate storage and parking, not lacking tenants until Oelsner cleared it in 2018 in anticipation of the rezoning. (The Real Deal also called it a “long vacant parcel.”)

This Times passage was also generous:

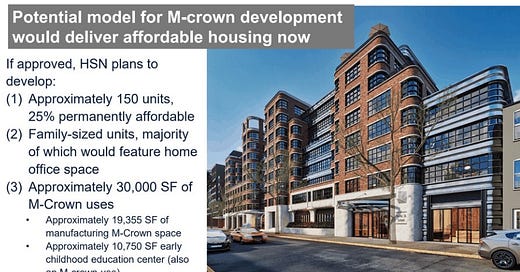

Oelsner’s plans called for a smaller building than other developments nearby. She wanted apartments big enough for working families, meaning no studios. She said the building would include an early childhood education center and space for industrial business.

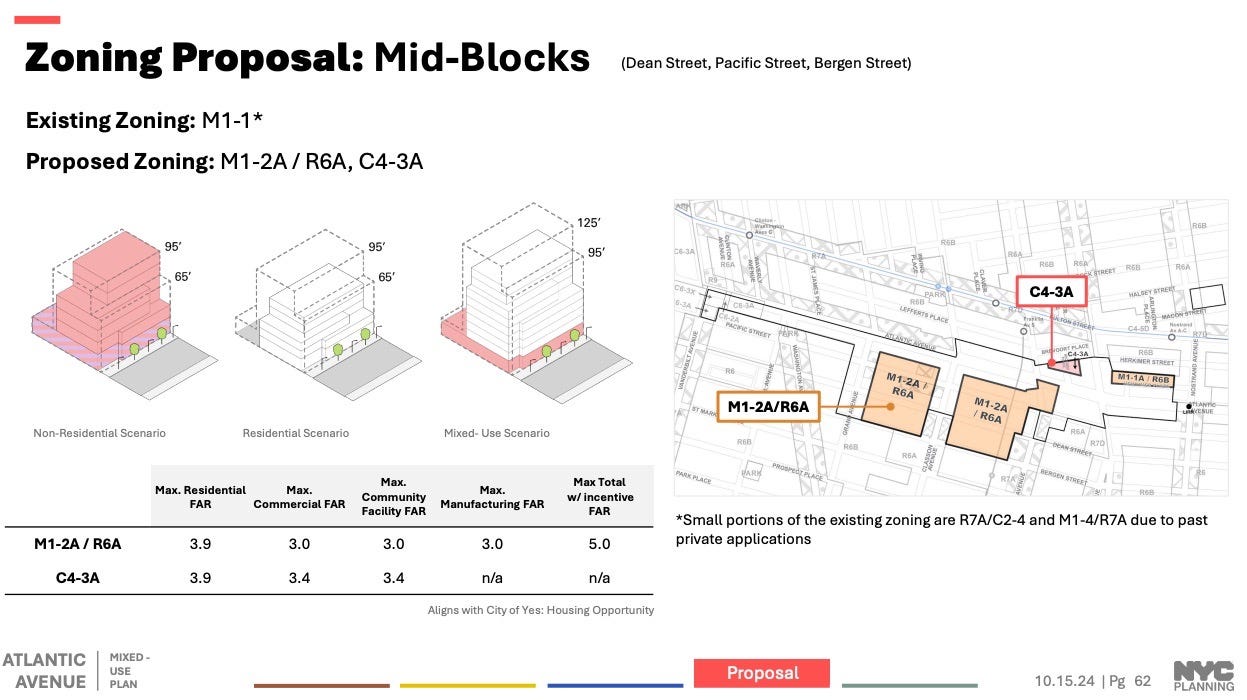

I’m not sure what “smaller” refers to. The adjacent 1010 Pacific and nearby 1050 Pacific are nine stories, as 962 Pacific was planned. Yes, the pending Atlantic Avenue Mixed-Use Plan, under certain circumstances, would allow for a taller building, 12 stories and 125 feet, at 962 Pacific.

The unusually deep site "ends up soaking up a lot of square footage," 962 Pacific architect Nick Liberis said at one hearing, "so you're able to keep the building lower."

(Yes, buildings along Atlantic Avenue were approved at 17 stories, but that’s a much wider street, so not comparable.)

As to no studios, the Times apparently was referring to the project presented to Community Board 8, but not necessarily the version the board agreed to support. The zoning would have allowed 199 units, not 150, but the applicants stressed they’d provide larger units.

At that Sept. 14, 2023 full board meeting, Lobel acknowledged that the size and configuration could change. He stated that, while the original proposal assumed one-, two-, and three-bedroom units, “my understanding is the configuration is between ones and twos.”

Oelsner, though, said the building would contain “ones, twos, and some threes… We’re trying to avoid studios.” In other words, it was in flux.

M-CROWN space

As to space for an early childhood education center and for industrial business, well, that was strategy to win over the Community Board, while gaining a distinct advantage.

Yes, one assumed benefit was the plan to devote most of the cellar, 19,355 square feet (plus a 1,030 sf ground-floor entry), to manufacturing uses, plus additional space to an early childhood education center, also a job-creating use under M-CROWN guidelines.

However, Land Use Committee member Kaja Kühl observed out that a below-ground location doesn’t count as buildable floor area, since it doesn't add space in the rezoning and doesn't represent a sacrifice of the developer's additional space.

“It's additional rentable space in my view,” she said. “And this is not necessarily negative because I think it's great. But I think we should be clear about this.” Another bonus to the applicant: that space would be swapped for the otherwise required 59-62 parking spaces, a costly endeavor.

Indeed, the building was to rely on a significant amount of space that doesn’t count as an upzoning, because it’s either below-ground or otherwise ineligible. 962 Pacific would’ve contained 214,602 gross square feet (gsf), a 39.6% increase over 153,695 zoning square feet (zsf). That’s far more than in nearby spot rezonings.

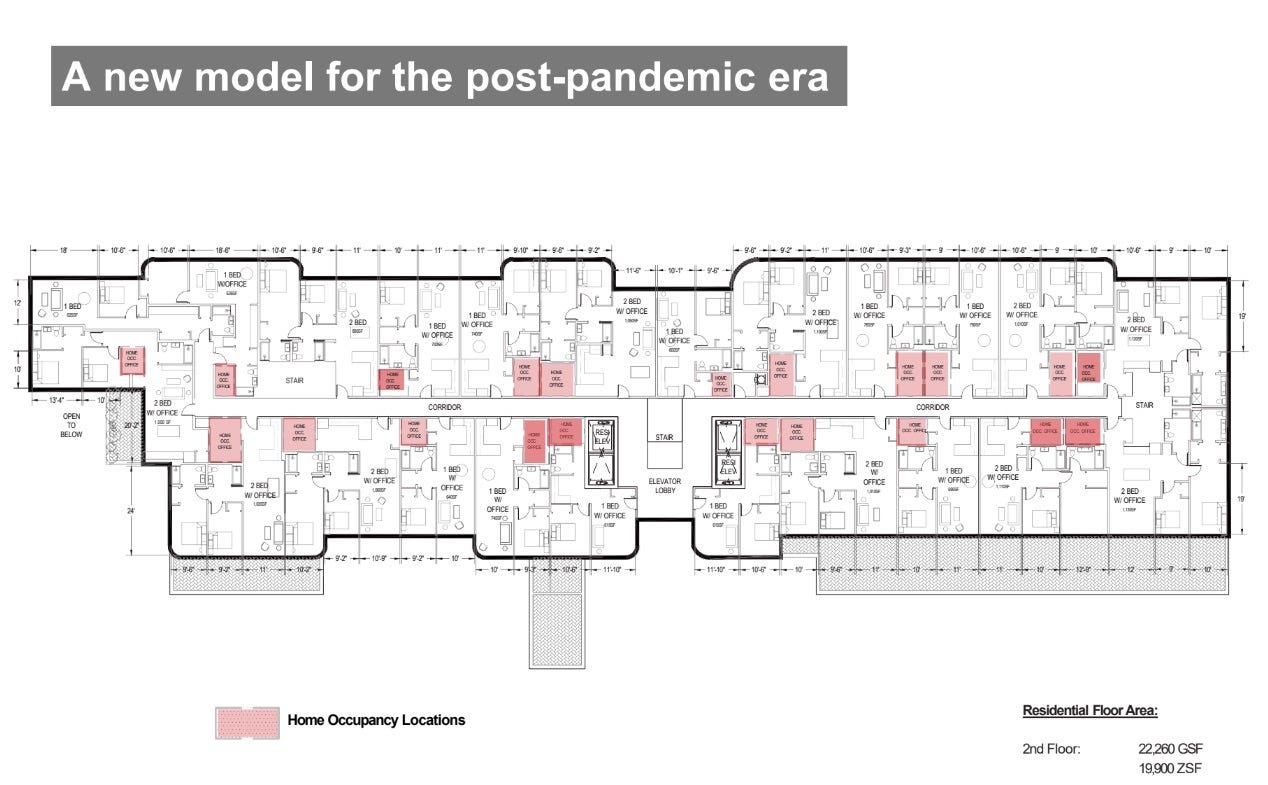

The home office space

Though unmentioned in the Times, the applicants touted the inclusion of home office space in many units, calling it a “new model for the post-pandemic era.”

That was also a pragmatic response to a site its architect described as “overly deep, it’s 110 feet deep,” leaving the team unable, as one City Planning Commissioner observed, to turn such windowless space into an extra bedroom.

Open space questions

One clear cumulative impact of spot rezonings, which add population, is stress on the area’s limited open space. 962 Pacific’s early childhood center was to have a garden, 3,250 square feet, and the building would have a residential garden, a modest 1,950 square feet.

Given such concerns, Oelsner said “we would be open to working with the Community Board on ways to open and make available these spaces for community use.”

At one meeting, Land Use Committee member Peter Krashes said he didn’t think the community would “choose to pass through the building to use this space” and asked if it could be moved to the street. The answer: no.

How many affordable units?

The Times, relying on HSN, stated the building was to include 110 apartments at market rate and 38 affordable ones, including 15 “very low-income,” at 40% of Area Median Income, 8 at 60% of AMI and 15 at 80% of AMI.

That conforms with Option 1 of the city’s Mandatory Inclusionary Housing, or MIH.

Yes, that was a version of the developer’s proposal, but the article ignores significant jousting.

Pushed by tenants like Mimi Mitchell focused on racial displacement, CB 8’s Land Use Committee sought double the number of deeply affordable units: 30 apartments at 40% of Area Median Income, plus the other pledged units. That would’ve meant 53 total affordable units, not 38.

(CB 8, confusingly, conveyed a less burdensome configuration, with 5 units at 60% of AMI and 18 at 80% of AMI, to the applicant, as indicated in the screenshot below. Land Use Chair Sharon Wedderburn acknowledged a typo in the resolution sent to HSN.)

Oelsner’s team countered, in a letter from Lobel, that the request was not feasible, but they had “stretched the building financially” and agreed to 48 affordable units, including 27 at 40% of AMI, 5 at 60% of AMI and 16 at 80%. of AMI. See excerpt below.

That was a significant increase, it prompted fierce debate at the full CB 8 meeting. The first vote, with 11 abstentions, failed to reach a majority in support. (Here are the minutes.)

After a break, the board tried again, with the discourse swayed, surprisingly, by a wild-card commenter, Peter Anekwe, who was the meeting to get his block more lighting. “Do you want 15 [deeply affordable units] or do you want 27? I think 27 is better,” he boomed, urging attendees to be realistic.

Veconi then proposed a motion: withhold support for the application unless the developer committed to its revised proposal. The motion was framed as 18% of units at 40% of AMI, 3% at 60% of AMI, and 11% at 80% AMI, so it would’ve delivered more affordable units if the developer increased the building’s total unit count.

That, in fact, was under consideration. “We’re trying to work [the total] out,” Oelsner said. “We might be a little more than 150.”

While Lobel had warned that the project likely wouldn’t be built if the affordable units were required to increase as overall unit count grew, the applicant team looked very pleased at the results.

Getting to yes

The commitment to 48 units, plus industrial space and $50,000 for anti-displacement services, expected by the Fifth Avenue Committee (FAC) would not have been part of the rezoning process, since it went beyond the city’s Mandatory Inclusionary Housing options.

It would’ve had to be locked in with a side deal—termed a “Community Benefits Agreement”—with a nonprofit organizations like FAC, with Hudson as the broker. That didn’t happen.

But it was expected, as Borough President Antonio Reynoso’s recommendation to approve the application included a condition that “Evergreen Exchange be included in the Community Benefits Agreement to provide support services for industrial businesses.”

The City Planning Commission (CPC) said it was “pleased to see the applicants are willing to consider higher percentages and deeper levels of affordability” than required, but acknowledged such decisions were outside the application’s scope.

At the CPC hearing, Lobel observed that CB 8 has a nonprofit, Friends of Community Board 8, for side agreements, and said “this applicant has agreed with the Community Board that they would enter into a binding agreement in the form of a Community Benefits Agreement or CBA.”

Later, Commissioner Leah Goodridge, without referencing CB 8’s request, asked if the applicant would add deeper affordability.

“I think so,” Lobel said, but that would come at City Council. He noted that, in previous negotiations, Hudson “asks and gets more.” The applicants, he said, “have the opportunity to do more. I can't necessarily say what that is right now, but I know it will it will end up being more.”

Did that mean that Oelsner’s team had given up on their pledge of 27 apartments at 40% of AMI? Unclear, but they may have wanted, at that point, to avoid committing to an increase in affordable units if unit count grew.

Goodridge, a tenants’ rights lawyer, would be the Planning Commission’s only dissenter.

What’s next?

The second Times article stated:

For Oelsner’s project, next year is most likely too late. She has abandoned her plan for the nine-story apartment building for now, and 962 Pacific remains vacant. She has not said what she might do next.

Unreported by the Times, Oelsner and her lawyer, playing chicken with the community board, suggested that the failure to pass the rezoning would lead to construction of a last-mile distribution center for packages or a bus parking lot, both fueling unwelcome traffic.

A distribution center, though, requires a serious construction commitment.

The summary line on Brooklyn Needs Housing. She Has a Vacant Lot. Why Can’t She Build?, stated that Oelsner “may just give up.”

Surely a building will be built, and Oelsner may get a good payday, even if she doesn’t build it. It’s worth noting that Oelsner’s lender, Knighthead Funding, in the past year noted that Oelsner’s refinancing involved a development site with 266,000 buildable square feet, as seen in the screenshot below.

That’s larger than proposed and, as far as I can tell, permitted under the AAMUP rezoning, so it’s… confusing.

Was Oelsner “local”?

The Times described Oelsner as having “made the case that her family had been part of the community for years, operating a Pontiac dealership.”

That hardly captures her slippery claims of commitment to the neighborhood. CB 8, for all its purported opposition, never quite pinned down where Oelsner, who appeared remotely at numerous Land Use Committee meetings, actually lived.

She also provoked skepticism among some Committee members, given her somewhat stilted recitation (on video: October 2022, December 2022, March 2023, August 2023) of their plan.

“It’s going to be hard to find a small developer like us that is committed to Brooklyn,” Oelsner told The Real Deal. “If this project gets in the hands of another big developer, they’re not going to have the thoughtfulness to give back.”

As I wrote, that was a self-serving statement from an applicant who has a Charleston, SC, residence and whose company has a Port Washington, NY, address. (“I have a residency in New York,” she said when asked about her tenure in the neighborhood.)

“We have been active participants in the neighborhood,” Oelsner told the Land Use Committee, “and we have viewed Brooklyn in decades.”

That, however, could mean retroactively. After all, her team had a not-so-reliable track record. Lawyer Lobel told the City Planning Commission that the 1010 Pacific applicant was a long-term owner, intending to develop and operate the building. That didn’t happen.

Also, Lobel assured Cumbo that all proposed 103 units at 1010 Pacific would be two bedrooms, and it was not contingent upon anything. Wrong.

While Oelsner told the Land Use Committee “we are active supporters of Community Board 8,” Lobel later amped that up, claiming to the City Planning Commission that “we are members of Community Board 8.”

Was Oelsner planning to build?

“What we're trying to do… is work with all of you so that we can maintain control over our property, and that we could then bring in somebody, a developer, that echoes the same values we have and that the community has,” Oelsner told CB 8. “We fear the consequences could be dire if we do not proceed with our application soon.”

Would the Oelsners maintain a majority ownership in a joint venture? “We pray to God," she responded, "we can keep this property and we can have a controlling interest." That’s hardly definitive.

Perhaps Oelsner would have brought in a partner that would commit to the plan as negotiated. (Or that was locked in by a side agreement.)

As discussed further below, I wouldn’t discount the involvement of Totem, co-founded by former Downtown Brooklyn Partnership head Tucker Reed.

Local opposition?

Both the 962 Pacific parcel and a contrasting one on the Upper West Side, to the Times, “met immediate opposition,” as Crown Heights neighbors “wanted more apartments to be available at lower rents and were concerned about parking.”

The second Times article claimed:

Members of the community board fought Oelsner’s project. At a September 2023 meeting, one member said she worried about where the new residents would park. Another wondered why all of the units were not going to be affordable.

That’s misleading. Disparate comments—here’s one on parking; here’s one on 100% affordability—at the August 2023 meeting (not September) do not opposition make.

Yes, affordability was an issue, but that, as Oelsner’s team knew, was something to be negotiated. Despite some carping, the Community Board easily supported a swap of parking for job-creating space.

From the Times:

The 962 Pacific Street development became embroiled in the politically fraught debate over how to plan for growth in a neighborhood that has gentrified rapidly. The changes have angered longtime residents who feel they are being pushed out.

“In this particular area, people felt like these big buildings keep going up,” said Crystal Hudson, a Democrat who represents the neighborhood on the City Council. “We’re not addressing broader community needs.”

She’s right that a comprehensive rezoning would address far more. But Hudson could’ve made a stronger case why it was right to draw the line before this spot rezoning, as opposed to any previous ones.

Drawing the line

Her aide Andrew Wright told CB 8, at the start of the process, that the Department of City Planning "has limited resources, and we need to make sure that all of those resources are fully focused on this neighborhood rezoning process, and even one private application will pull from that and will take away from our ability to fully realize” the AAMUP plan.

One key question: could AAMUP deliver as much, or more, affordability, than what Oelsner had agreed to? As of now, that seems unlikely, though CB 8’s Land Use Committee last night recommended an additional deep affordability option for Hudson to consider when getting AAMUP approved. (That might require subsidies.)

What’s the context?

The Times described Crown Heights as “an area, which for decades had been home to mostly Black and Orthodox Jewish families, [which] has seen an influx of white residents in recent years.”

Wait a sec. Crown Heights is a huge neighborhood, with 962 Pacific, for example, a 1.5-mile walk from the heart of the Chabad Hasidic community.

The more specific the context is the extended influence of Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park, which prompted spot rezoning efforts east of the project’s Vanderbilt Avenue border. 962 Pacific is a little more than two blocks away (0.4 mile), from the easternmost project building, 550 Vanderbilt.

The megaproject has left bitterness, as Times commenter South of Albany wrote:

Empire State Development Corporation and the half-finished development of the Barclay’s Center / Pacific Park are largely to blame for the local distrust of the state’s involvement, CPC and the Pacific Park developers in Crown Heights, CB8, and adjacent community boards. The lies, half truths and lack of real public input has soured most of these ULURP applications. The Pacific Ave building will be build- they all are eventually.

Dubious journalism

Other news coverage has been questionable. The Real Deal ended its coverage of the rezoning vote with this paragraph:

“I think it’s unfortunate that the community is going to have to wait longer for some important benefits that they need and deserve,” said Michelle de la Uz, a former City Planning Commission member who has been following the Pacific Street drama.

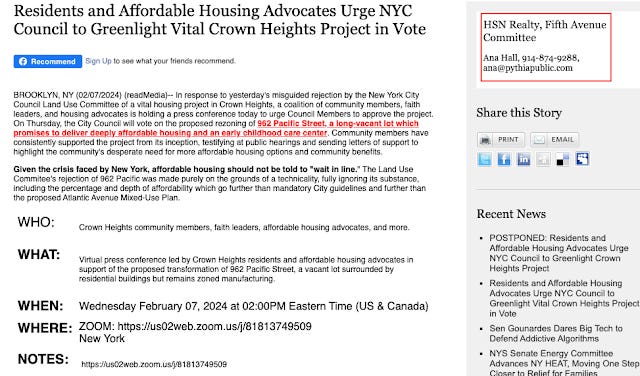

As I wrote, de la Uz was no disinterested observer. A previous Real Deal article even stated that she was "not involved in the project," which I criticized by pointing to the Brooklyn Borough President's statement that the applicant had partnered on affordable housing with the Fifth Avenue Committee (FAC), which de la Uz heads.

Also, FAC likely would’ve been the recipient of the $50,000 in anti-displacement services promised in a 962 Pacific "Community Benefits Agreement."

“Proposed transformation of long-vacant Crown Heights lot might be a model for mixed-use development,” the not always credible Brooklyn Daily Eagle proclaimed Aug. 30, 2023 in what was more a press release than an article.

The no-byline article ended by buffing the owner:

Oelsner cites her longstanding ties to the Crown Heights community as her motivation for the proposed development.

Another Eagle “article,” Community-inspired affordable housing project in Crown Heights in limbo at City Council, Jan. 25, 2024, ended by quoting de la Uz, described as “Executive Director of the Fifth Avenue Committee, a Brooklyn-based housing non-profit,” but didn’t mention their partnership with the developer.

The plan, she said, “absolutely fits into the AAMUP framework, and even goes further.”

Footnote: the future of Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park

Note that de la Uz and Veconi are key people in the coalition BrooklynSpeaks, which in 2014 negotiated a new 2025 deadline for the Atlantic Yards affordable housing—a deadline that won’t be met and must be renegotiated.

BrooklynSpeaks, which has made the only organized effort to advocate for Atlantic Yards improvements in recent years, is thus seen by elected officials as speaking for the community.

Would BrooklynSpeaks, given the Fifth Avenue Committee’s affordable housing mission, support a future reconfiguration of Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park, including a significant increase in scale, as long as it prioritizes affordable housing?

Footnote: the role of Pythia Public Affairs

After Hudson announced her opposition to the project, Pythia Public Affairs, whose Ben Branham had joined Oelsner’s team at CB 8’s September meeting, organized and announced a press conference with the Fifth Avenue Committee, urging the Council to ignore Hudson and the typical process in which members defer to their colleagues.

As shown in the screenshot below, under “Recent News” at right, that press conference was, for some reason, postponed and never held.

I would wager that Pythia, or a firm like it, helped place the Eagle “articles.”

Footnote: Anekwe’s role

Commenter Anekwe’s role at CB 8 was surely unexpected, but there was more to that story.

On a GoFundMe page for Anekwe, who was reintegrating into society after years in prison and “immense reflection and with remorse for his actions as a young man,” Pythia’s Branham posted a comment:

I saw Peter Anekwe speak at a Community Board 8 meeting last night and was inspired by his passionate and articulate comments which helped change the mood of the entire room. I would love to follow up with him if he is open to sharing his contact info.

Branham, as shown in this screenshot, contributed $100 to Anekwe’s fundraiser. William Oelsner, Nadine’s husband, contributed $250. So did Totem’s Reed.

Anekwe later reiterated his support for the revised deal at the City Planning Commission hearing. He has since joined CB 8.

Footnote: the Totem connection

Other circumstantial evidence points to the potential role of Totem as a partner on 962 Pacific.

At the City Planning Commission, another project backer was Totem VP Elizabeth Canela, who some might remember as a staffer at original Atlantic Yards developer Forest City Ratner.

Also testifying was Daniel Lebor, a partner at the real-estate firm TerraCRG, who with firm head Ofer Cohen brokered the 2023 sale of 1057 Atlantic Avenue from a team led by Totem and BEB Capital to Douglaston Development.

(BEB Capital supplies most funding for recent rezoning projects credited to Totem. It’s based in Port Washington.)

News reports claimed Douglaston paid $66 million for the rezoned (for residential use) parcel, though the sale document says $65 million. BEB paid about $24.9 million: parcels $13.5 million, nearly $4.8 million, and $6.6 million. Terra CRG also brokered those sales.

So that land purchase, plus the cost of the ULURP process, was alchemized by rezoning into a significant return, even as the building will deliver 30% affordable housing (137 units), of which two-thirds will be affordable to low-income households at 60% of Area Median Income, under Mandatory Inclusionary Housing Option 2.

The beneficiaries included two BEB entities, with the signatory Lee Brodsky, owning about 87.2% of the shares, and two holding companies, one with Reed as signatory and the other with TerraCRG’s Cohen as signatory, each owning 6.4%.

Separately, a partnership involving BEB Capital, Totem, Cohen, and SK Development gained $121 million in financing for a 187-unit development at 737 Fourth Avenue in Sunset Park.

The project includes a Community Benefits Agreement signed with the Fifth Avenue Committee and others. The Fifth Avenue Committee also works with Terra CRG on leasing retail parcels it controls.

Enter Ailanthus

If 962 Pacific resurfaces, the partner might not be Totem but rather a new “platform” called Ailanthus, which involves two Totem principals and Terra CRG’s Cohen.

From a May 13, 2024 press release headlined Brooklyn Real Estate Leaders Launch Housing Creation Platform to Tackle NYC's Affordability Crisis, produced by Berlin Rosen, the go-to public relations firm for real estate:

Ailanthus, a new housing creation platform that aims to create 10,000 new units in New York City over the next five years, was launched today by Ofer Cohen, Tucker Reed and Vivian Liao. The principals have collaborated on several Brooklyn projects over the last five years, with a pipeline of approximately 1,500 housing units through developments such as 1057 Atlantic Avenue and 737 Fourth Avenue.

…Ailanthus takes direct aim at the capital assumption that entitlement efforts are riskier, drawing on a track record of success of assembling sites, partnering with community stakeholders and successfully entitling large housing projects. By focusing on community-driven entitlement processes, Ailanthus will unlock a significant pipeline for housing creation that has often been overlooked by investors.

In other words, they claim a white hat, while recognizing they can, in Cohen’s words, “right size the risk profile of entitlement efforts from an investment perspective.” Translation: find properties that can be vaulted in value thanks to rezoning, while gaining “community” buy-in from nonprofit partners.

That, indeed, is possible when few watch closely or push back.

Pursuing equity

Ailanthus also committed an unspecified fraction of profits “to local nonprofits” via the community foundation Brooklyn Org. The press release quotes foundation head Jocelynne Rainey: they’re “proud to work in partnership with Ailanthus to address one of the largest challenges we face in building a more equitable Brooklyn: the lack of truly affordable housing.”

Is this the best way to pursue equity? Would Brooklyn Org be interested in bolstering efforts, as articulated by the Pratt Center, to tax home-flipping or to capture value uplift that otherwise goes to “front-runners” and land speculators?

Those are the kinds of questions a newspaper series on the housing crisis also might address.

There's such a thing as a story being too comprehensive. I think the key point here is that by rejecting the spot rezoning, the Council member will end up with fewer affordable units at a higher AMI than she will get at 962 Pacific under AAMUP, the broader rezoning that will pass today. There's a brief mention of that in this incredibly thorough piece, but it will be lost amid all the other details.