It's the Oversight, Right?

New York State has let the developer off the hook. Why no legislative hearings?

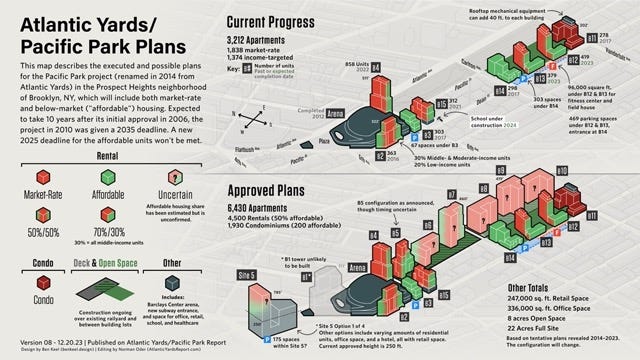

As 2024 begins, Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park is at a crossroads. I’ll publish my 2024 preview soon on my Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park Report blog (and newsletter readers will see it in the Sunday roundup).

After immersing myself in this project starting in the summer of 2005 (!)—and attuned to it since early 2004, when I started attending public meetings, not long after the December 2003 project announcement—I have the benefit and burden of memory.

So I remember the March 2010 groundbreaking for the Barclays Center.

Then-Governor David Paterson, who’d been elevated to the post by Eliot Spitzer’s surprise resignation, declared, "To those who have supported the project and to those who opposed the project, I guarantee that we will be scrupulous in our monitoring of the contract that Forest City Ratner signed with the state to make sure that everything we were promised, we receive."

That wasn’t true at the time—New York State, to some surprise, had already allowed a 25-year buildout for a project that was long promised to take ten years.

And it’s certainly not true now. So, if the executive branch of government doesn’t do its job, the state Legislature and others should step up.

Changing cast

Paterson didn’t last long, and successors Andrew Cuomo and now Kathy Hochul have given the project a long leash.

Forest City, by 2014, had sold 70% of Atlantic Yards going forward—excepting the arena and the first tower, 461 Dean—to Greenland USA, the opaque subsidiary of a Shanghai-based, significantly state-owned conglomerate, Greenland Holdings Corp.

Greenland changed the project’s name to Pacific Park—a reboot that, I contended, aimed for distance from historical taint.

After the joint venture built three towers together, Forest City’s parent, Forest City Realty Trust, called a pause, citing rising costs and increasing competition from apartments rising in nearby Downtown Brooklyn.

By early 2018, Greenland had taken over all but 5% of Forest City’s share. By the end of the year, Forest City was defunct, having been absorbed by Brookfield Properties.

The Greenland-controlled development company then sold leases to three parcels to established local developers, two to TF Cornerstone and one to The Brodsky Organization, and jointly developed another tower with Brodsky.

Now what?

Since then, however, the pandemic, rising construction costs, the loss of the 421-a tax break, and the cost of the platform—which would support six towers—over the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s Vanderbilt Yard have all stalled the project.

Compounding that is the parent company’s troubles in China, where its stock price and credit rating have dropped significantly. That’s hardly unique to Greenland, given China’s roller-coaster real-estate economy.

Now Greenland is facing the foreclosure of its interest in six development sites over the Vanderbilt Yard, given overdue loans to immigrant investors under the EB-5 program. (More on that soon.)

Keeping watch

Should New York State, via Empire State Development (ESD), the state authority that oversees/shepherds the project, have gotten wind of Greenland’s financial troubles and that foreclosure?

Sure, if they had been “scrupulous in [their] monitoring.”

They weren’t. So that suggests a lack of competent governance, legislative oversight, and civic/journalistic attention.

Moreover, the Atlantic Yards Community Development Corporation (AY CDC), the advisory body set up in 2014 to monitor the project’s commitment, has been largely ineffective, partly by design (gubernatorial appointees, uncertain schedule, inadequate information shared) and partly by performance (under-informed board members).

Board members Gib Veconi and Ron Shiffman, respectively, in August asked for a financial analysis of the project’s future and a state accounting of how the affordable housing delivered compares with what was promised. The first request won a unanimous AY CDC vote.

ESD, which lost its key Atlantic Yards staffer earlier this year, has not delivered the responsive documents. And while the (purportedly) advisory body is supposed to meet quarterly, it hasn’t met since Aug. 2.

Missed opportunities

As I wrote in December 2022, one lesson from this project is that complicated contracts can get ignored, whether willfully or carelessly.

We learned that during the kerfuffle over the unbuilt (and largely forgotten) Urban Room, the atrium attached to the unbuilt flagship tower, “Miss Brooklyn,” once planned to loom over the arena.

Instead, the developer has long floated plans to move most of that bulk across the Flatbush Avenue to Site 5, longtime home of the big-box stores P.C. Richard and the now-closed Modell’s.

Since Site 5 has already been approved for a large tower, creating a much larger two-tower project, and allowing the developer to profit from that unused bulk, would require a new round of project approvals.

ESD was distinctly uninterested in enforcing those fines, which totaled $10 million by May 2023. The state authority does have a loophole—a "right to refrain" from enforcement—so that situation may persist.

That posture put into focus a more significant enforcement deadline: May 31, 2025, by which the developer is supposed to complete the project's 2,250 affordable housing units or pay $2,000/month in fines for each missing unit.

That deadline won’t be met. ESD has so far indicated no intention to pursue the fines, which would total more than $21 million a year for the 876 (or 877) missing units.

The willingness of ESD to enforce, suspend, or renegotiate the fines may be key to anyone bidding on Greenland’s development rights during the Jan. 11 foreclosure auction.

No financial statements from Guarantor?

Another obligation ignored seems even more significant in retrospect.

The project's Guarantor, if not filing financial reports as required by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, is supposed to deliver annual audited financial statements to ESD, formerly known as ESDC.

That’s according to the project's Development Agreement, excerpted below.

While the original Guarantor was Cleveland-based Forest City Enterprises/Forest City Realty Trust, since 2014, that guarantor has been--presumably--Greenland Holdings Corp.

Those statements must be "prepared in accordance with sound accounting principles by an accounting firm of national standing," and accompanied by a "certificate signed by a Qualified Certifying Party"--a top executive--"stating that such annual financial statement presents fairly the financial condition and results of operation of Guarantor."

The Guaranty, according to the Development Agreement, "shall remain in full force and effect" until performance in full of the Guaranteed Obligations or payment of the Liquidated Damages, and would be binding on the original Guarantor's successors.

But ESD, in response to my Freedom of Information Law request, said it had no such annual audited financial statements, nor the annual accompanying required certificates signed by a Qualified Certifying Party. (I also contacted the p.r. firm representing Greenland, and got no response.)

Why that's important

That's concerning. First, at least one obligation in the original Development Agreement that has liquidated damages remains, notably that $10 million fine for the Urban Room.

The more significant obligation is the May 2025 affordable housing deadline and the associated liquidated damages. If Greenland has no money—or won’t find money—to pay off its loans, it likely isn’t ready to pay those liquidated damages.

But the concept is clear: the parent company is supposed to guarantee project obligations, and ESD should keep track of whether that Guarantor is financially sound.

Remember, the financial health of Greenland has been in question since as far back as 2016, when its credit rating went from investment-grade to "junk." Last year, it sunk to Selective Default, with specific notes in Default.

Representatives of Greenland USA publicly claimed there's nothing to worry about. "We're continuing to do exactly what we've done, which is continue to invest substantial amounts in the project and continue to execute as we've had since we came into the project in 2014," said Greenland USA executive Scott Solish in June 2022.

Since then, though, the promised platform, though presumably on the brink of a construction start, did not move forward and Solish, perhaps not surprisingly, exited for a more stable company.

ESD should’ve known better.

Barriers to compliance

Now Greenland, as a company traded on the Shanghai Stock Exchange, surely does produce quarterly and annual financial reports.

But it's less likely that they have been translated into English. Such translations have not been circulated publicly, at least.

As to whether an "accounting firm of national standing" has participated, well, we don't know.

Obligations and the Guarantor

In exchange to the city and state funding directed to the project, that Guarantor, at the risk of significant financial penalties, agreed to perform various obligations:

starting and completing the arena within six years

achieving Substantial Completion of Phase I of the project, within 12 years of the Project Effective Date (or by 5/12/22, given the 5/12/10 "Effective Date")

by the Outside Phase I Substantial Completion Date (12 years), completing Phase I improvements, as well as the Urban Room

Most of those obligations have been met. The arena opened in September 2012. With the B4 tower (18 Sixth Ave., aka Brooklyn Crossing) beginning leasing in January 2022, the developer had achieved Substantial Completion of Phase. But not the Urban Room.

Extensions possible

As I wrote in January 2010, the developer must begin construction of the platform over the railyard no later than the 15th anniversary of the Effective Date, or May 12, 2025. That once seemed like an easy hurdle. Not any more.

As to Phase II, the developer by May 12, 2035 must build at least 2,970,000 gross square feet, the school (done), an intergenerational community center with space for at least 100 children for publicly funded day care, and at least 8 acres of Open Space.

If the developer doesn’t finish, well, ESD can terminate any lease where construction hasn't begun. In other words, they get the property back.

However, that Termination Option will be exercised in accordance with Section 17.5, which states that ESD has up to two years to deliver a Termination Option Notice, but, if not, the lease terms will be extended five years. And within a year after that, ESD can again deliver another Termination Option Notice. And that process can continue.

So there are potential extensions. Remember, ESD has a "right to refrain" from enforcement, as well.

Who’s the monitor?

For now, ESD seems to have pursued a right to refrain from the monitoring that Paterson promised back in 2010.

Few elected officials, civic groups, or journalistic entities still pay attention. But it’s the state Legislature’s job to ensure that the executive office fulfills its obligations.

(Update: I should note that the coalition BrooklynSpeaks previously called for a city and state investigations, as I wrote—though the original press release is missing.)

The Legislature, in the history of Atlantic Yards, has not exactly looked closely at the project. When Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver, an ally of the developer, held power, he stymied any action from the Democrat-controlled Assembly.

Only when the Senate flipped from Republican to Democrat was an oversight hearing held, in May 2009. It was a frustrating but partly illuminating hearing.

Today, the questions asked in the hearing notice, set by (the late) Sen. Bill Perkins, persist: “Atlantic Yards: Where Are We Now, How Did We Get Here, And Where Is This Project Going?”