Is the Barclays Center the "Linchpin" of Atlantic Yards? No, and That Matters

The arena and team helped get the project approved, but didn't leverage the jobs and housing. Decoupling ownership sacrificed cross-subsidization. The state could step in.

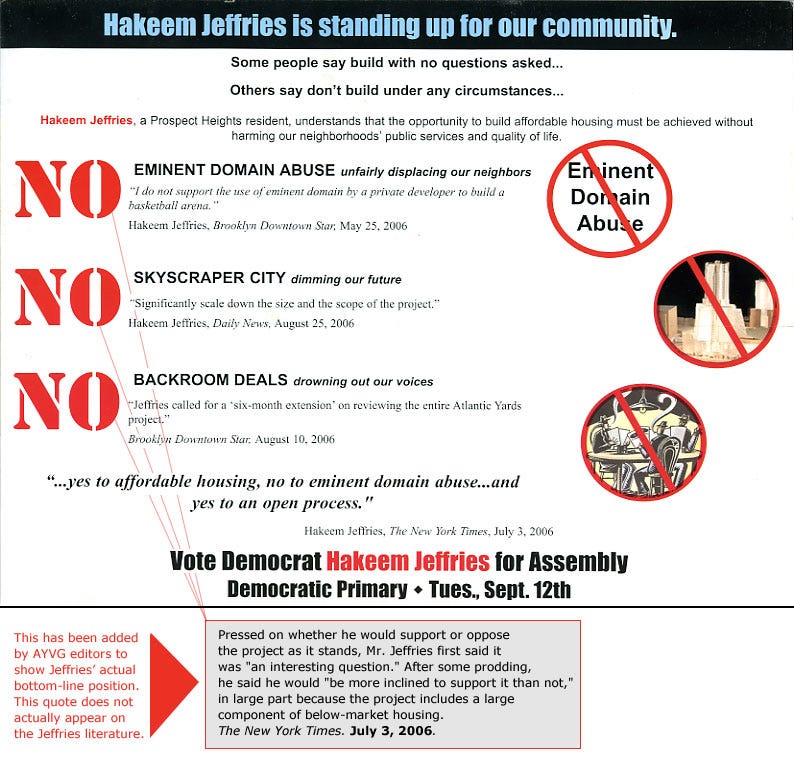

In the spring of 2006, when running for an open state Assembly seat, Hakeem Jeffries (now Democratic leader in the House of Representatives), positioned himself carefully regarding Atlantic Yards, a controversial proposal still facing approval by New York State.

The planned arena might be needed to "create the jobs and housing," Jeffries opined, but he opposed eminent domain—the state’s taking of private property for public use or public purpose—without "a clearly defined public benefit."

That positioned him as the relative centrist in a race against Atlantic Yards opponent Bill Batson, and Freddie Hamilton, a signatory to the Atlantic Yards Community Benefits Agreement.

Jeffries won easily. His Atlantic Yards stance was too murky to detract significantly from his advantages in establishment support, charisma, and shoe leather.

What was the arena for?

Was the arena needed to “create the jobs and housing,” as well as the crucial infrastructure? Or was it used to gain political and community support for developer Forest City Ratner’s (FCR) effort to control 22 acres of valuable land?

A "pro-development city official" would call the arena a "Trojan Horse" for "an overly dense project,” as reported by Peter Slatin.

Team + arena = “linchpin”

In March 2006, FCR head Bruce Ratner told investors that he tried to go to every home game for the New Jersey Nets, which he had bought to move to Brooklyn.

“It was really the linchpin of this development. Without the basketball team and arena, we wouldn’t be able to do this development. It created the opportunity,” he said. “We very often start our projects with an anchor, in this case it’s an arena and a basketball team.”

So the scarce commodity of an NBA team, and the venue in which it would play, would leverage the larger project.

What’s a linchpin?

But were they the linchpin, which, according to Merriam-Webster, is “one that serves to hold together parts or elements that exist or function as a unit”?

On May 29, introducing a segment regarding the state’s failure to enforce penalties for the project’s missing affordable housing, a WNYC host said of the Barclays Center, “years ago, it was the linchpin of a multi-faceted project” by developer Forest City Ratner to deliver not just world-class entertainment but also new housing, including affordable housing.

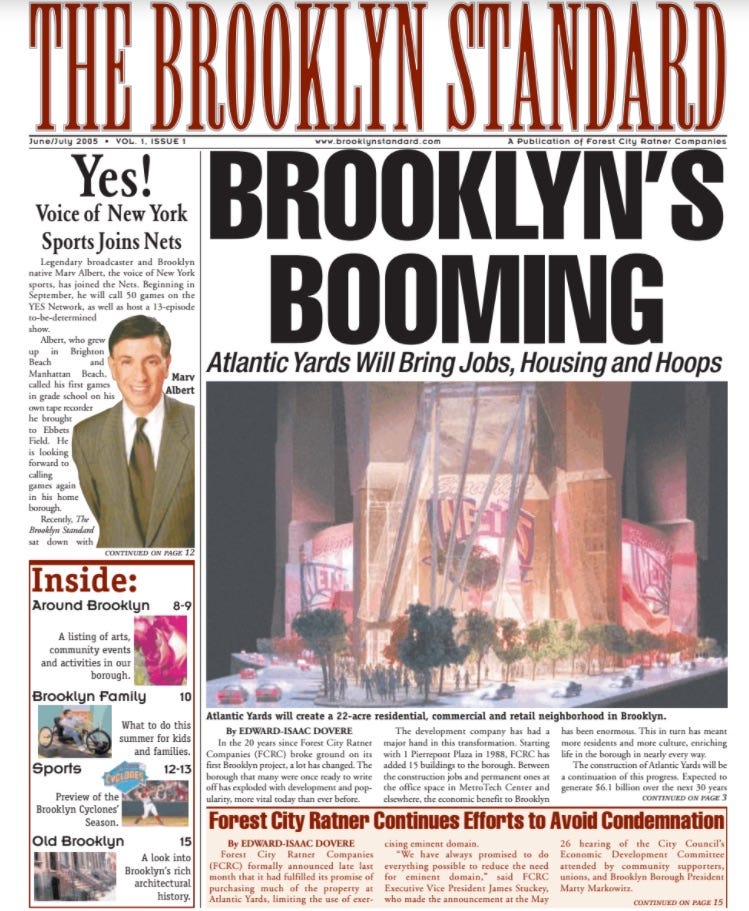

Indeed, Forest City claimed Atlantic Yards would bring “jobs, housing and hoops,” as shown in the screenshot below from The Brooklyn Standard, a promotional “publication” that looked like a newspaper distributed in 2005. (It lasted two issues.)

The slogan “Jobs, Housing, and Hoops” would appear on t-shirts and buttons. It was a package deal—or was it?

In February 2007, a New York Daily News editorial hailed arena sponsor Barclays, claiming that the annual naming rights payments “will help finance thousands of units of affordable housing.” (Not so. The money helps pay off construction debt.)

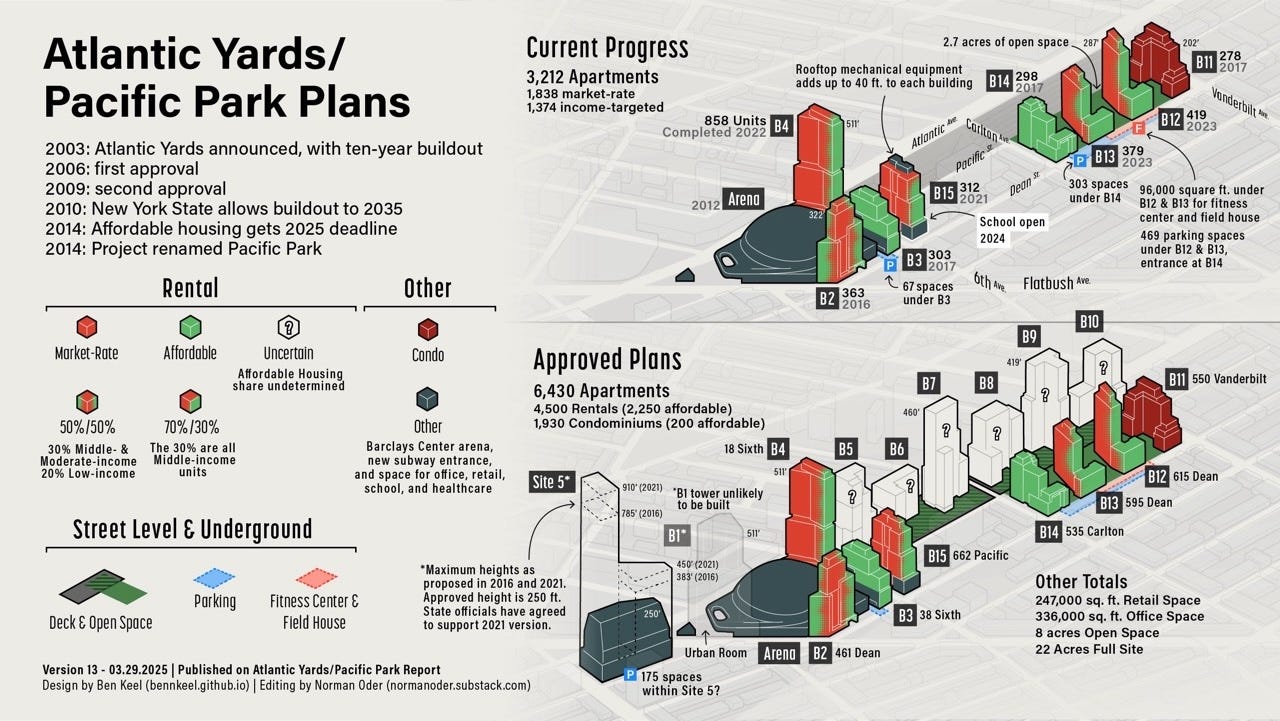

As we’ve learned, the new arena has not been accompanied by the promised total of permanent jobs or construction jobs, nor the costly platform to support six towers (B5-B10) over the railyard. (See below.) After all, Forest City ditched the office towers and, with the project barely half-complete, construction jobs have lagged.

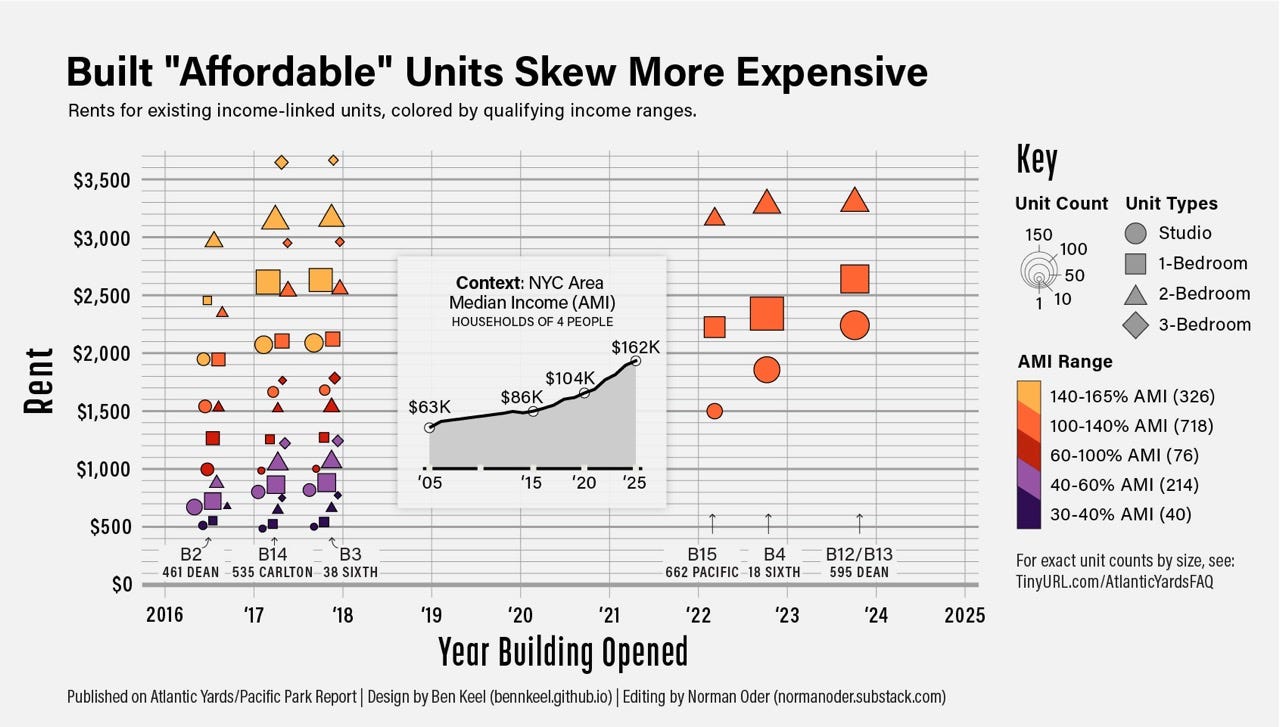

Even worse, while about half of the 6,430 approved apartment have been built, the 1,374 below-market “affordable” units have been skewed to middle-income households, with the provision of such housing tied to available subsidies, tax breaks, and low-cost financing.

The arena today is very much decoupled from the remaining Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park project, which involves eight towers (of 16 approved) and significant infrastructure. So, by not covering the railyard with a platform for towers, the project has not yet cured the purported “blight” that justified eminent domain.

Arena as linchpin

The “linchpin” rhetoric has been periodic.

In June 2009 and September 2009, the New York Times described the arena as the project’s “linchpin.” Three years later, it called the arena “the cornerstone of the development” while “the Nets… would be the linchpin.”

After the arena opened in 2012, Architectural Record’s Joann Gonchar offered “a mostly positive but ultimately cautious review, praising Barclays for “feel[ing] as though it belongs on its site,” but warning “it can't be declared a civic triumph just yet,” given that the project could take 25 years.

“Not until a few of the planned 14 residential towers are built, including some of the promised 2,250 units of affordable rental housing, and at least a few of the anticipated eight acres of public space are completed,” she wrote, “will anyone be able to determine if Atlantic Yards, with the arena as its linchpin, will add to or detract from the streetscape of Brooklyn.”

I’ll be writing separately about the impact of the project, as constructed so far, on the streetscape, but another looming question was: would the arena be the linchpin to get the platform built?

Ownership split

Gonchar’s observation was wise. While the arena and team helped get the project approved, it did not guarantee any other elements would be delivered. It was not, in reality, a linchpin.

That fate was ordained perhaps well before the arena opened. In 2010, Bruce Ratner sold a majority stake in the Nets and a minority stake in the arena operating company to Russian oligarch Mikhail Prokhorov.

In 2014, Greenland USA bought a 70% stake in the project going forward, excluding the arena company and the modular tower (B2, aka 461 Dean St.). Changing the project’s name to Pacific Park, Greenland would build three towers in a joint venture with Forest City, then acquire nearly all of the latter’s share.

It would lease two tower sites to TF Cornerstone and one to The Brodsky Organization and build another in a joint venture with Brodsky. Since November 2023, however, Greenland has faced the loss of six tower sites in foreclosure.

The winners decoupled

Meanwhile, the arena and team rocketed in value, along with the NBA.

Prokhorov in 2015 acquired the rest of the team and the arena company from Forest City. In 2017, he began a process in selling his holdings, known as BSE Global, to Alibaba billionaire Joe Tsai, who completed the purchase in 2019, at a valuation of $3 billion to $3.3 billion.

Tsai, after acquiring and rebuilding the WNBA’s New York Liberty, last year sold a 15% stake in BSE Global to the family of Julia Koch, at a $5.8 billion to $6 billion valuation. This year, they sold a “mid-teens” stake in the Liberty alone at a $450 million valuation. That’s enormous “value creation.”

A “linchpin” but…

The “linchpin” rhetoric persists. Developer MaryAnne Gilmartin, Ratner’s successor as CEO, in this May 2024 video said the project was “centered around Barclays Center. Barclays Center was the linchpin.”

Today that term should provoke chagrin or caution. After all, the connection has been cut.

On Gothamist, commenting on the state’s unwillingness to impose penalties on the missing affordable housing, one reader asked, “Why, why, why did they ever let them build the stadium before the affordable housing?? Like it’s such an incredibly obvious and avoidable mistake.”

Maybe it wasn’t a mistake. Maybe it was an accommodation to the developer’s preference. Forest City wanted to get the money-losing New Jersey Nets to Brooklyn. The rest was “market-dependent,” at least if the state provided a long leash.

Restoring the linchpin

New York Times architecture critic Michael Kimmelman, in his 2012 review, argued that arena financial gains—at that point unclear—should factor into "the subsidized housing equation.” That hasn’t happened, but it still could.

New York State State, which oversees the larger project and owns the arena site, retains leverage. Tsai wants the plaza outside the arena to be made permanent, rather than having a giant tower built there, as the state plan still allows.

Also, the next Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park developer would rather move that bulk across the street to another site. In doing so, New York State could require Tsai and his fellow owners to pay for the privilege of gaining that permanent plaza.

That could cross-subsidize the housing and/or the platform needed for railyard towers. BSE Global also could be required, as BrooklynSpeaks suggests, to pay for a publicly operated quality of life enforcement unit.

Bonus: other “linchpins”

Note that the term “linchpin” has been used in other Atlantic Yards contexts.

In 2009 by The Architect’s Newspaper used the term to describe the role of starchitect Frank Gehry, who brought Forest City new cachet, until his designs, post-recession, were deemed too expensive.

In 2012, City Limits described the promised affordable housing as “the political linchpin of the Atlantic Yards deal—the element that brought community groups and many local politicians onto Ratner’s side,” but warned it was “now the missing link.” Today, that warning lingers.

Excellent article. I remember Joanne Gonchar’s comment. While us small group of protesters marched around the site before eminent domain took it all we talked about just this point. The arena romance was being used to get the approval for subsidies and tax breaks without further guarantees. The pro arena pols like our borough president at the time piled onto that the “blighted” narrative as well.

Thanks!