Eminent Domain Reminders from "Battle for Brooklyn": Bogus Blight and Dubious Public Use

Did condemnation serve a real "public purpose"? If so, shouldn't the public get a cut of arena/team profits?

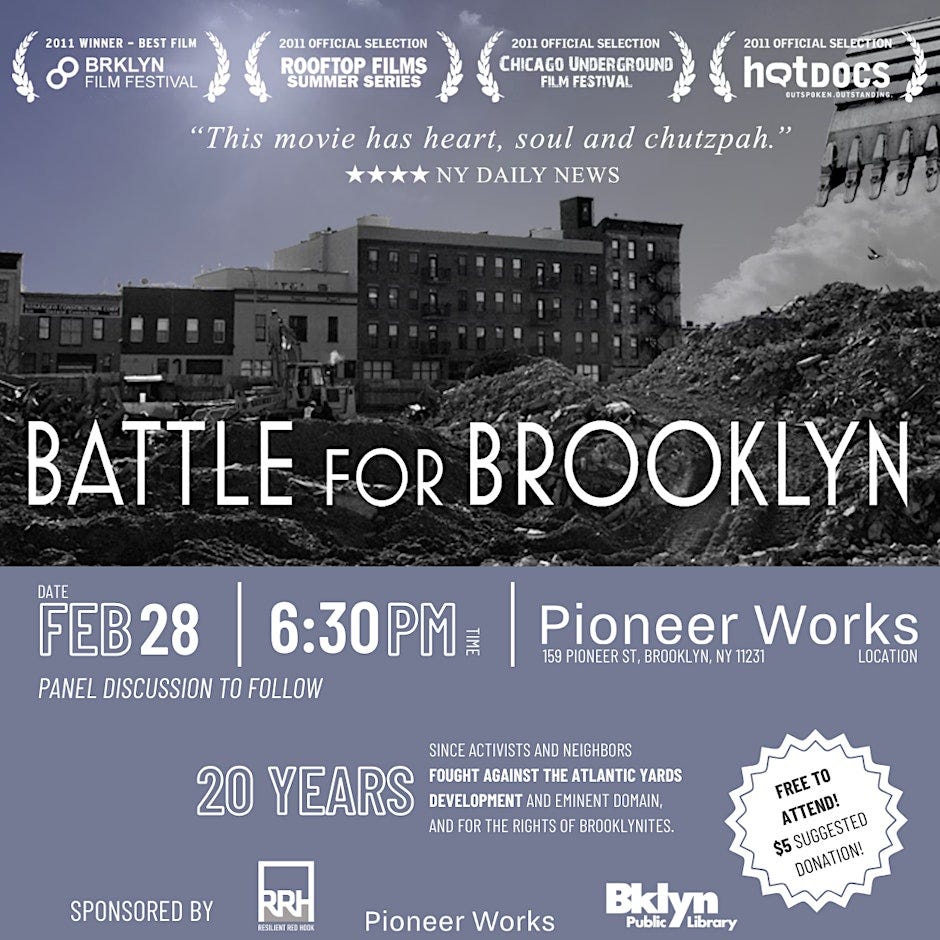

The organization Resilient Red Hook is screening the 2011 Atlantic Yards documentary Battle for Brooklyn on Feb. 28 at Pioneer Works, part of a film series on community activism, as the neighborhood faces a controversial large plan involving the Brooklyn Marine Terminal.

A panel discussion afterward involves Atlantic Yards activists. Also, directors Michael Galinsky and Suki Hawley, and producer David Beilinson, of Rumur, will attend. (Tickets are sold out.)

I’ll be away. I’m not an organizer, but I helped edit the announcement, which states, in part:

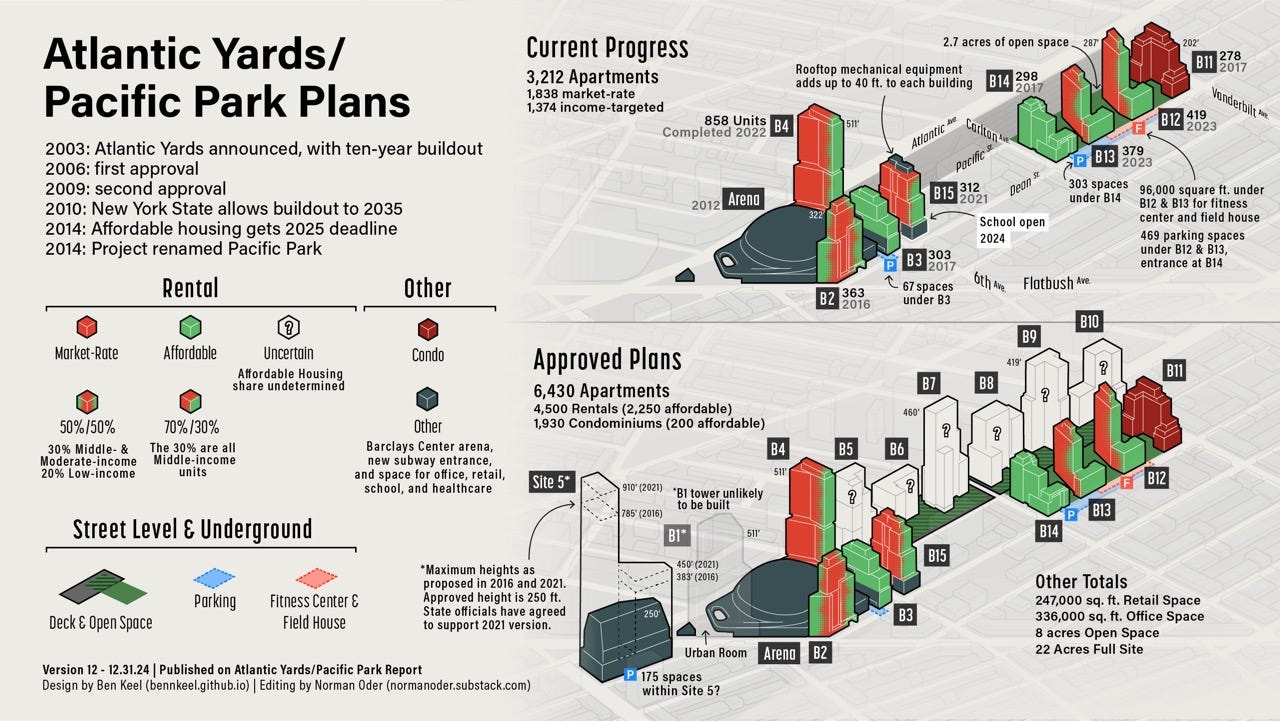

Today, the project, with eight towers and the Barclays Center, is half-finished, with public benefits far behind promises. While the real-estate company sponsoring the project exited at a loss, the owners of the Brooklyn Nets, enriched by the new subsidized arena, are big winners.

The arena’s not just subsidized, but also a beneficiary of dubious eminent domain, a focus of the film. That, glaringly, has not succeeded in enabling development over the MTA’s Vanderbilt Yard.

After all, according to New York State, “a principal goal of the Atlantic Yards Land Use Improvement and Civic Project is to transform an area that is blighted and underutilized into a vibrant, mixed-use, mixed-income community,” including “eliminating the blighting influence of the below-grade Yard and the blighted conditions of the area.”

About the film

Battle for Brooklyn, released while the arena was under construction, is dated, given the vastly changed Brooklyn context and (partial, delayed) progress on the project. (See map.) Some flaws in both the narrative and the Atlantic Yards resistance are more visible.

Still, the movie remains compelling and key messages resonate. Next week, I’ll publish a long essay based on rewatching the movie. (Yes, this one isn’t short.) Here’s a quote I gave Gothamist (which yesterday excerpted just a fraction):

While some scorn Atlantic Yards opponents as resisting urban progress (note: they did propose an alternative for developing the publicly-owned railyard), a crucial legacy, as captured in the film, is enduring skepticism of the government-developer alliance. That’s borne out by the project’s many delays, the yet-uncovered (and purportedly 'blighted'--part of the justification for eminent domain) railyard, and the failure to fulfill transformative promises of jobs and affordable housing.

NY State forced to defend the indefensible

Some in the Atlantic Yards debate say the ends justify the means. One Gothamist commentator acknowledged the tension: “while i think it's good that brooklyn got a pro sports team again, every aspect of how it happened was absolutely horrible.”

Many don’t know the means. So I’ll focus here on eminent domain.

Protagonist Daniel Goldstein, co-founder of Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn (DDDB), was no storybook eminent domain victim, with his limited tenure in his apartment, like Susette Kelo (and her “little pink house”) in New London, whose case went to the U.S. Supreme Court.

However, his principled and ornery stand, as spokesman for the Atlantic Yards resistance and lead petitioner in the eminent domain cases, forced New York to defend a dubious condemnation. (Goldstein will be on the panel Feb. 28.)

If a good prosecutor could "indict a ham sandwich," as the aphorism goes, a New York government entity could "condemn a kasha knish," once quipped attorney Michael Rikon, who represents condemnees. That’s what happened.

Bogus “blight”

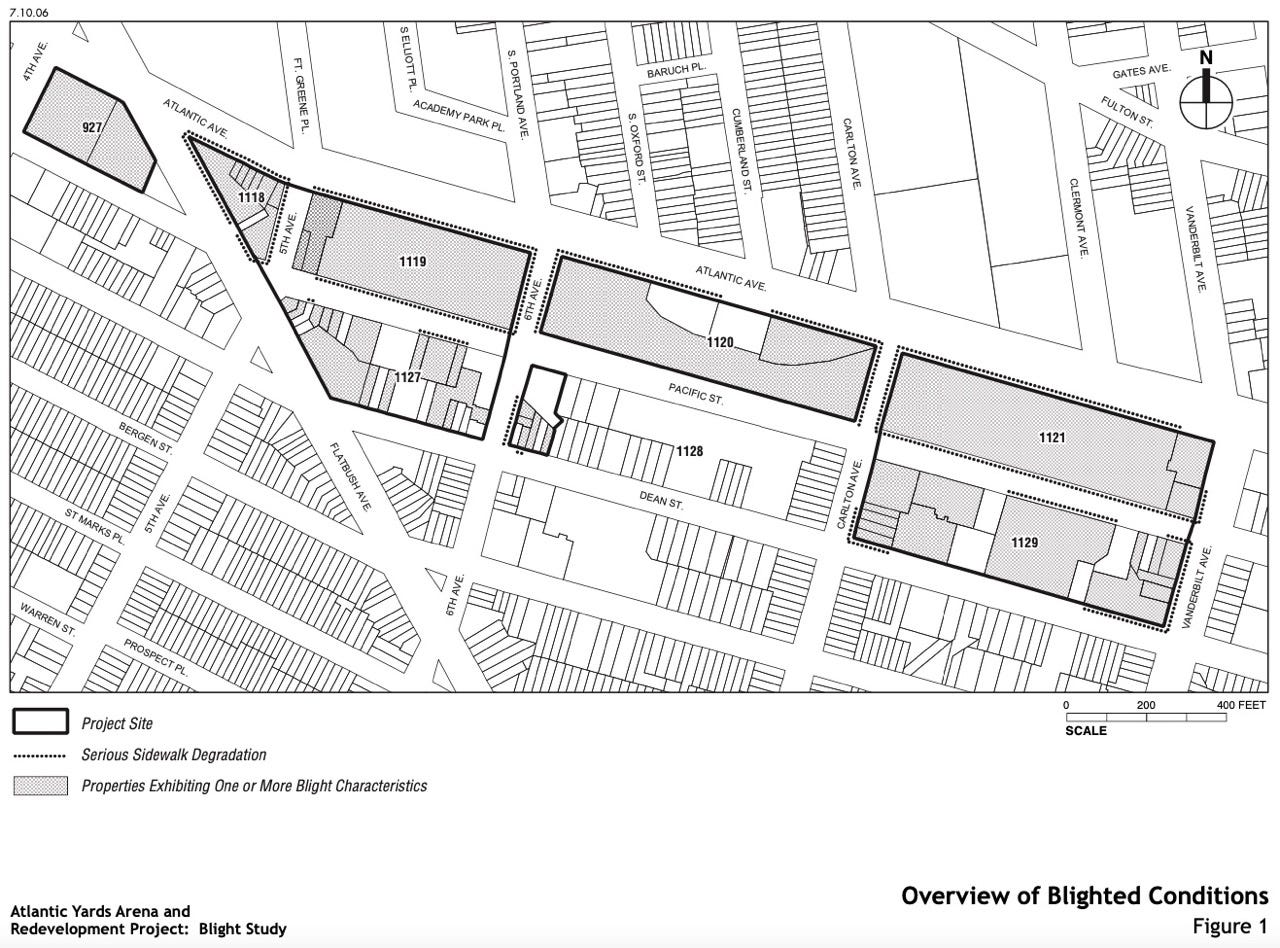

Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC, now ESD), the state authority overseeing the project had to approve condemnation, based on alleged blight. (Remember, no local elected official had a vote.)

The scene below at the key ESDC board meeting, shot by the film’s producers for their Kickstarter campaign, was excerpted in the film. It includes Goldstein and fellow activist Patti Hagan (who’ll also speak at the screening) recounting their incredulousness at the state’s rubber stamp.

At the meeting, a staffer woodenly reads a boilerplate description: “A Blight Study was prepared which documents blighted conditions on the project site. ESDC intends to exercise the power of eminent domain to remove these blighted conditions.”

Blighted conditions, not a blighted neighborhood. After all, an irregular, 22-acre site, with a missing “tooth” in the middle and one parcel separated by wide Flatbush Avenue, couldn’t be a neighborhood.

What conditions? Cracks in the sidewalk, graffiti, and weeds could have been ameliorated first by abatement, not by condemnation. The claim of underutilization—like a house built to less than 60% of its developable bulk—could’ve applied to large parts of Brooklyn.

The bustling P.C. Richard and (at the time) Modell’s big-box stores, at the Site 5 parcel across Flatbush Avenue, featured no “unsanitary and unsafe” conditions. Still, they were considered “critically underutilized.”

100 feet of blight?

As I wrote back in 2006, it was dubious that somehow the blight map ended 100 feet east of Sixth Avenue, after the fifth house in the photo below left. That little house, long owned by Jerry Campbell’s family? Well-maintained but just too petite.

Why did the developers need that 100-foot piece of land? Not to “build a school” (as New York State later said), which occupies the first five floors of the tower constructed, dubbed Plank Road. The school was initially supposed to be elsewhere.

That 100-foot rectangle, not part of the project’s original outline, surely related, I wrote, to the developer's plan for construction staging, while building four towers simultaneously with the arena. That didn’t happen.

Well, some might say, isn’t it better that a larger building provides homes—er, with the only “affordable” ones for middle-income households—for more people, plus a school, at that site? The response: do the ends justify the means?

The “blighted” railyard

Consider that the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s (MTA) own Vanderbilt Yard, used to store and service Long Island Rail Road trains, was considered blighted, according to the ESDC’s Blight Study.

Why? “Unsanitary and Unsafe Conditions” such as being “overgrown with vegetation and littered with trash and debris,” while “several small storage structures and interior walls are painted with graffiti,” with adjacent sidewalks “in a condition of disrepair” and weeds growing along the fence.

But what if neighbors could clean it up?

I covered the Sept. 23, 2007 community cleanup of the “blighted” conditions on Pacific Street between Fifth and Sixth avenues organized by Deb Goldstein, Daniel’s sister. (Daniel Goldstein’s apartment building, by the way, is visible in the photo lower left.)

Underutilization, too

The 165,000 square-foot railyard parcel between Sixth and Carlton avenues (aka Block 1120), according to the Blight Study, could accommodate up to 165,000 zoning square feet of built space under current zoning, or a one-story building.

However, ”it is occupied by an active open rail yard and one 300 gsf [gross square-foot] building, utilizing less than 1 percent of the lot’s development potential.”

That’s bogus. The gubernatorially controlled MTA could not only have abated those “Unsanitary and Unsafe Conditions,” it also could’ve been asked whether utilization was feasible.

Construction over a railyard requires a platform to preserve the railyard functions. That’s expensive. It only pencils out if a developer can build much larger buildings than the current zoning allows. Land use changes, involving a city rezoning or a state override of zoning, would be required.

However, the MTA had not tried to develop that parcel or put the railyard development rights up for bid, before Forest City Ratner, the original developer, proposed Atlantic Yards.

Blight passes

The New York State Court of Appeals waved all that off. "It may be that the bar has now been set too low," wrote Judge Jonathan Lippman for a 6-1 majority, in "what will now pass as 'blight'… relying upon studies paid for by developers, should not be permitted." But that, he declared, was a job for legislators.

Judge Robert Smith's dissent decried the ESDC's "self-serving determination," adding "that the elimination of blight, in the sense of substandard and unsanitary conditions that present a danger to public safety, was never the bona fide purpose."

Though consultant AKRF found an area "characterized by blighted conditions," he wrote, “They did not find, and it does not appear they could find, that the area where petitioners live is a blighted area.”

Today, glaringly, two of the three railyard blocks await a platform for development. (The western third didn’t need a platform, since the arena parcel—about half of which includes that third railyard block—was built below grade.)

The railyard storage and service activities were moved from the western third to the eastern one. It’s a valuable property, even without the platform. But the “blight”—the rationale for eminent domain—hasn’t been remediated. Somehow, though, the blight didn’t infringe on the nearby housing market.

Pursuing some accountability

Less than two months after that Court of Appeals decision, the ESDC was forced, at a Jan. 5, 2010 oversight hearing called by State Sen. Bill Perkins, prompted by Columbia University’s planned expansion into West Harlem, to defend its tactics.

"Has AKRF ever found a situation in which there was no blight?" Perkins asked, provoking laughter from the audience. (This hearing isn’t in the film.)

ESDC General Counsel Anita Laremont said she couldn't answer. She then added, sternly, "AKRF does not find blight. Our board finds blight. AKRF does a study of neighborhood conditions and they give us the report."

Not quite. The firm, as I discovered thanks to a Freedom of Information Law request, was contracted to "prepare a blight study in support of the proposed [Atlantic Yards]." That’s what it did. Moreover, as the filmmakers’ video shows, the board was a rubber stamp.

Actual public use?

The leadoff quote in Battle for Brooklyn involves eminent domain, defined as “The right of the government to take private property for a public use, usually with just compensation of the owner.”

That’s imprecise, as the Fifth Amendment states, “nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.” (See the kerfuffle about just compensation for Goldstein.)

Note the difference between “public use” and “a public use.” The latter seemingly forecloses the history of federal jurisprudence, evolving to the infinitely expandable notion of public purpose, which could include tax revenues, housing, and jobs. New York State law is narrower.

The Atlantic Yards eminent domain case, as captured in the film, includes a useful exchange during the state Court of Appeals argument in Albany. Matthew Brinckerhoff, attorney for the petitioners (in a case funded by DDDB donors), claims, “Those confiscations violate New York’s public use clause because they are justified on the hope of economic development.”

What, he’s asked, constitutes public use?

“I think an important distinction here is,” Brinckerhoff responds, “if this arena were truly owned by the government for a civic purpose, much like a museum or a cultural institution, you would at least have a better argument—”

What, he was asked, did he mean by “truly owned”?

“Here there’s a series of leases, one dollar a year,” Brinckerhoff responds. “And the reason that was done was to comply with some of the language in the Urban Development Corporation Act.”

It didn’t matter

That argument turned out to be a sideshow, at least under the state constitution.

As Lippman wrote, even if actual public use were required “and it is not—it is indisputable that the removal of urban blight is a proper… predicate for the exercise of the power of eminent domain.”

Smith, in his dissent, wrote that he was pleased that the majority did not follow Supreme Court jurisprudence, which equates “public use” with public purpose, “thus leaving governments free to accomplish by eminent domain any goal within their general power to act.”

However, he said the court shouldn’t “defer to ESDC's determination that the properties at issue here fall within the blight exception to the public use limitation.”

“Truly owned”?

Let’s go back to whether the arena would be “truly owned” by the public.

ESDC (now ESD) owns the parcel, which it leases to the issuer, an alter ego called the Brooklyn Arena Local Development Corporation, or BALDC. That entity leases the arena to ArenaCo, Brooklyn Events Center, which is an affiliate of BSE Global, the firm that operates the arena and owns the Brooklyn Nets.

That fig leaf of public ownership enables tax-free financing, which could save more than $250 million compared to taxable financing. (See estimate of an initial $161 million revenue loss, then a $90 million saving after refinancing.)

Tax exemptions galore

The tax-exempt property means the arena operator doesn’t pay taxes. Instead, it makes payments in lieu of taxes (PILOTs) to pay off the construction bond. The current tax bill avoided exceeds $110 million.

Defenders would argue that the Barclays Center has the same PILOTs deal that the stadiums for the New York Yankees and New York Mets got, while Madison Square Garden, home of the New York Knicks and New York Rangers, is separately tax-exempt.

True. That justifies none of them.

No wonder the Independent Budget Office, always in search of low-hanging fruit, annually suggests that the Madison Square Garden tax exemption be lifted. No wonder various Council Members, including Brad Lander (now Comptroller), in 2020 signed onto a letter from a colleague, calling for city sports venues to pay taxes.

Public uses, public purposes

With the railyard uncovered, that purported blight hasn’t been removed. Construction plans have stalled, as developer Greenland USA, Forest City’s successor (and, for a while, joint venture partner) on the residential sites, put up the six railyard development sites for a loan that’s now in foreclosure.

Questions remain unresolved about the future participants, the timeline, and the terms.

The bottom line, though, is that eminent domain has enriched not Ratner but Mikhail Prokhorov, the Russian oligarch who bought the team and later the arena company from Forest City, then sold the holding company BSE Global to Alibaba billionaire Joe Tsai at a huge profit, at least $600 million, perhaps $1 billion. (The transaction was valued at $3 billion to $3.3 billion.)

Tsai, riding the increase in value in a scarce commodity, last year sold a 15% stake to the family of Julia Koch, widow of the notorious right-wing funder David Koch, gaining a reported $688 million without giving up control. (The transaction proceeded at an overall valuation of BSE Global, which had added the WNBA’s New York Liberty, of $5.8 billion to $6 billion.)

A “rational” belief

In the federal eminent domain case, which preceded the state one, Atlantic Yards was seen as fostering various public purposes, including blight removal, a new arena, and the creation of housing, including 2,250 affordable apartments.

Given such “classic public uses whose objective basis is not in doubt,” the Second Circuit Court of Appeals ruled, the project “may not be successful in achieving its intended goals,” but the test is whether the state “rationally could have believed that the [eminent domain taking] would promote its objective.”

That’s a low bar.

DDDB legal director Candace Carponter said in response, "We maintain that the government's motivation in using eminent domain for Atlantic Yards is not to benefit the public, but rather, to benefit a single, very rich and powerful developer.” (She’’ll be on the panel Feb. 28.)

It ultimately didn’t benefit Ratner much, as his firm—unwilling and unable to play the lucrative long game—exited at a loss. (Of course, if Ratner had lost the court case, it would’ve been a bigger loss.)

But even if the government had mixed motives, doesn’t proceeding without real competition in the bidding, honesty in the Blight Study, or safeguards in the aftermath undermine the legitimacy?

Public support

In a scene early in Battle for Brooklyn, Council Member Letitia James asserts, “We do not need to publicly finance an arena.” Well, taxpayers don’t pay the debt, though allowing a tax-exempt site, and tax-exempt PILOTs, is pretty helpful.

But we did publicly enable it and publicly support it, not just through tax-exempt land and tax-exempt financing, but also via direct subsidies of some $305 million (much but not all for the arena), free public streets and free public property, plus other tax breaks, the ability to sell naming rights, and more.

Today, it’s glaring that eminent domain enriched Prokhorov and Tsai while not delivering the jobs, job training, and affordable housing promised.

In a powerful scene captured in the film, Goldstein at a May 2009 state Senate oversight hearing, warns, “The project that was approved in 2006 no longer exists”—the camera pans to project supporters like the Rev. Herbert Daughtry and Marie Louis of the job-training group BUILD, looking somber—“not the jobs, not the housing. No one can say what the project is, or what it costs. No one can tell us that, yet they say they’re breaking ground this fall.”

What now?

Similar questions persist today. No one can say what the project is, or what it costs.

The project’s now at a crossroads. The arena’s finished, but the required affordable housing won’t be built by May 2025, and the developer—whoever that is—must renegotiate, just as Ratner did, captured in the film.

The deadlines and likely the configuration will change. The state will be asked to bend.

The renegotiations don’t directly involve Tsai, but he (and the Kochs) will be a key beneficiary if the state agrees to move the bulk from the unbuilt “Miss Brooklyn” tower, once slated to loom over the arena, across Flatbush Avenue to Site 5, enabling a giant two-tower project, instead of a substantial but shorter tower.

That would make the arena plaza, valuable as both a safety valve for gathering crowds and a canvas for advertising and promotion, permanent.

The “temporary” plaza was implicitly predicated on the common ownership of the arena operator and the project’s master developer, which meant they could cross-subsidize each other. Today, ownership is separate.

The state could make the arena operator pay. As I’ve argued, why not map it as parkland and charge a licensing fee? Or demand an additional annual payment in lieu of taxes?

There’s a “rational basis” for that, too.

solid as always