The Barclays Center's Unwise Financial Forecaster

Go-to consultant CSL in 2009 said the new arena would reap huge profits. Their own report refuted that. Philadelphia awaits.

For those hoping to build sports facilities, it’s important to have purportedly expert estimates of income, profit, and tax revenues.

That helps convince public officials of the plan’s viability and, in the case of bond issuances, helps get an investment-grade rating, which lowers the cost of debt. (“Junk bonds,” because of higher risk, pay higher interest rates.)

And if even if the forecast turns out to be irresponsible, the new arena still might, as in the case of the Barclays Center, supercharge the value of the main tenant, like an NBA team.

2009 fictions

In Brooklyn, the developers—and later operators—of the Barclays Center turned to Conventions, Sports & Leisure International (CSL International, or CSL).

In 2009, CSL prepared an arena financial feasibility study, part of the prospectus for tax-exempt bonds. As detailed below, CSL’s own numbers, in a follow-up 2016 report, demolished the previous predictions. Not that CSL copped to it.

The “Wile E. Coyote of the sports stadium racket”

First, some background. Subsidy skeptic Neil deMause, via his invaluable Field of Schemes site, in January 2020 called CSL the “Wile E. Coyote of the sports stadium racket,” detailing a long history of overstating facility revenues and public benefits.

Nevertheless, CSL provides “cover for team owners and elected officials who want a 400-page rationale for what they were hoping to do in the first place,” he wrote.

More recently, CSL has been hired by the city of Philadelphia to conduct the economic analysis and projections for a proposed downtown arena that would house the NBA’s Philadelphia 76ers and is dubbed, at least for now, 76 Place.

The team owners and developers, who predicted a taxpayer windfall ($1B in new revenues! maybe more!) without publicly sharing any studies, are funding the city’s report but didn’t choose the consultant. Then again, the city chose, from an RFP, the consultant any team owner would pick.

The report was due in December, so it’s long overdue. On April 1, the Philadelphia Inquirer reported none of the agencies involved in this and other studies—including a community-impact report—could predict when they’d arrive. Sports economist J.C. Bradbury has already tweeted scorn.

Boosters presumably want data to show this arena would be successful without cannibalizing the 76ers’ current home, the Wells Fargo Center, which would still host the NHL’s Philadelphia Flyers. The two arenas, according to the 76Place proponents, would both compete for events and expand the overall number.

Whatever CSL delivers, though, should treated skeptically. However Brooklyn seemed a plausible bet—an underserved market for events—it’s glaring how the Barclays Center missed CSL’s financial projections.

A quick bottom line

The graphic below mashes up part of CSL’s 2009 forecast of revenues, expenses, and net income in Brooklyn, with part of its 2016 report on the Barclays Center’s financial performance.

I’ve outlined comparable line items in the same color.

While the arena’s gross revenues, in the first two full years, did exceed predictions by a relatively modest amount, expenses were nearly triple that predicted.

So net income—or net revenue—was well below predictions, in one year essentially half.

The 2009 prediction

The larger chart below is from the financial feasibility study CSL prepared in 2009 to guide potential buyers of the tax-exempt bonds to finance the Barclays Center, built by developer Forest City Ratner. (The tax-exemption also lowers the cost of debt.)

Yes, the chart looks dense, but the colored rectangles isolate the key metrics. (Note that the chart assumed the arena would open by May 2012, though it didn’t open until Sept. 28, 2012.)

Halfway down the chart, projected arena revenues (blue rectangle), starting in the first full year, were assumed to start at $101.3 million and climb steadily. With total expenses (red rectangle) starting at $24.6 million and growing modestly, that left net income (purple rectangle), in the first year, at $76.7 million and climbing.

The key: DSCR

The result: a generous cushion to pay off debt, known as the Debt Service Coverage Ratio, or DSCR, indicated in the orange rectangle at the bottom of the above chart. That’s key to assuring bond buyers they’ll get paid.

In the first full year, the projected $76.7 million would easily cover the $27.3 million need to pay debt service, leaving a DSCR of 2.82, and climbing.

Ratings agency Moody’s was similarly optimistic (and paid by the issuer, a practice that’s not exactly arms-length ). On the same day, it estimated that the “10-year average” DSCR would be 2.85.

Both Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s (S&P) gave the arena bonds investment-grade ratings, barely a notch above “junk.”

That unrealistic DSCR estimate was likely crucial. According to the 2010 book The Business of Sports, the Fitch ratings agency set a minimum DSCR for a new facility at 2.25, in the "base case," when the arena appears operationally sound, and 1.75 for a "stress case," when there are more question marks.

The 2016 report

The Barclays Center was busy in its first year, holding high-profile events, reporting gaudy income (but not net revenue) figures and garnering awards. It surely helped that rival Madison Square Garden, in Manhattan, was undergoing a renovation.

However, that didn’t make arena operating company profitable. Let’s look at a 2016 CSL report, part of a prospectus for a refinancing, with bonds at lower interest rates.

At the Brooklyn arena, operating revenues (blue rectangle) in the first full year, 2013-14, were $120.4 million, way above the projected $101.3 million, though they dipped to $112.9 million in the second full year.

(The 2015-16 year was an outlier, because the arena vastly increased both revenue and expenses when the New York Islanders arrived.)

The key, however, is the red rectangle: operating expenses.

Operating expenses in the first part-year—a little over nine months—were $76.5 million! In the first full year, they were $74.5 million, which notched up only slightly the next year. (The later $130.6 million in expenses involved a guaranteed payment to the Islanders.)

That $74.5 million total was more than triple the projection, $24.6 million, in CSL’s 2009 report. That made it much tougher to cover bond payments.

Yes, Net Cash Flow was positive after the first part-year. Take Net Revenue, subtract PILOTs (payments in lieu of taxes), then add the O&M Reimbursement, a component of the required PILOTs that was kicked back for Operations & Maintenance. But it was way less of a cushion

No, CSL in 2016 didn’t explain the huge discrepancy—I’ll write separately about my best explanation—but kept a straight face and projected that, thanks to the refinancing that lowered interest rates, the arena would do fine.

Since then, it hasn’t met expectations either—that’s another story—and, with the pandemic, required new owner Joe Tsai to make capital contributions. Finally, though, it may nudge into the black.

Also, the refinancing helped significantly. While required PILOTs remained the same, the lower amount needed to pay bondholders (at lower interest rates) meant a larger amount of those O&M reimbursements, saving the arena operator an estimated $90 million cumulatively.

The bottom line

In its first part-year, despite headline performances by Jay-Z, Barbra Streisand, and more, the Barclays Center operator didn’t earn enough money to cover bond payments.

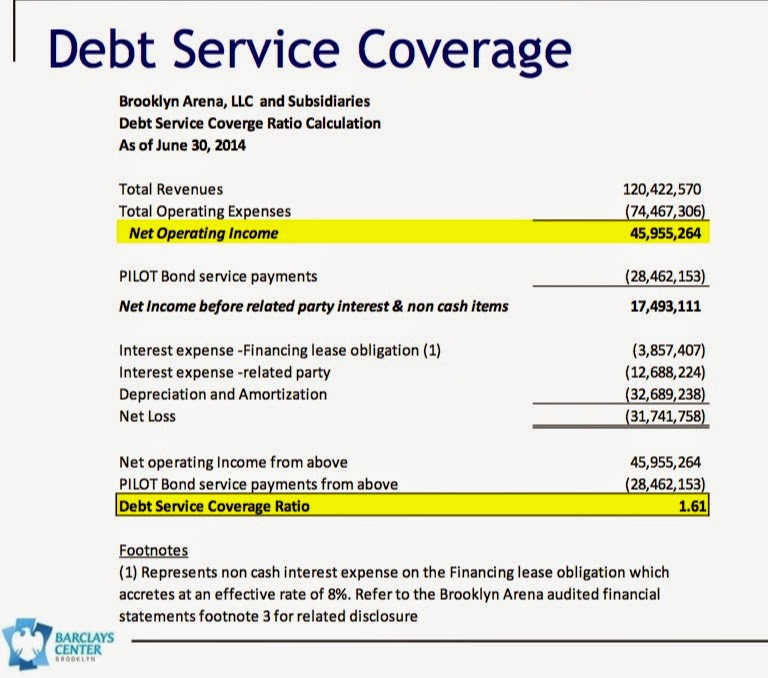

After the first full year, as indicated in the screenshot below, the DSCR was just 1.61. (I reported on this in February 2015.) In the second year, 2014-15, it plunged to just 1.29. That’s not much of a cushion.

The $45.96 million in net operating income was far below the $78.67 million predicted after the second full year.

Yes, the bond buyers were not stiffed. But had CSL and the ratings agencies been more skeptical, the bonds might not have gotten their investment-grade ratings.

That not only would’ve made the arena most costly—perhaps impossible?—to build, it would’ve alerted public officials that their investment in and support for the project deserved more scrutiny.

Ignore accounting losses

Note: I don’t take seriously reports by Forbes and others that suggest the arena company is deep in the red, nearly $76 million in the last fiscal year.

That relies on the more amorphous concepts of depreciation and amortization, which totaled nearly $71 million.

That helps with tax losses, but does not reflect the financial framing presented to bond buyers. I calculated the arena company’s net operating income—$99 million in revenues minus $83 million in expenses—as a little over $16 million.

However, the arena company had to pay more than $21 million in interest expenses on the bonds. That means a negative DSCR. Revenues couldn’t cover expenses.

So Tsai, the billionaire owner of the team and the arena company, had to make an $18 million capital contribution. This next fiscal year, FY 2024, may be the first in four years when such a contribution won’t be necessary.

The arena boosts the Nets

It’s important to recognize that, despite the Brooklyn arena’s financial underperformance, it’s helped the Nets’ value skyrocket, as NBA teams reap the benefit of new media rights, sponsors, and international attention.

That helped Mikhail Prokhorov, the Russian oligarch who bought the team from developer Bruce Ratner, make a huge profit—even if it’s “only” $600 million—and likely will help Tsai.

Forbes recently valued the team and arena company at $3.85 billion. Sportico valued the Nets, valued at $3.98 billion, 13th in the league.

But Tsai, according to not-so-clearly sourced reports, may sell 10% to 15% of the team, at an astonishing valuation of $4.8 billion, without losing control of the team.

Awaiting CSL in Philadelphia

Similarly, if a downtown arena gets built in Philadelphia but does not deliver the tax revenues or event revenues projected, it likely would vault the team’s value, as Sportico has suggested.

CSL declares itself “a solutions-based company that has a proven track record of successfully delivering best-in-class services for the most visible and iconic venues, destinations and sports teams across North and South America.”

Well, it depends on what you mean by “best-in-class.”

As deMause noted, CSL since 2011 has been owned by Legends Entertainment, which just happens also to market venue concessions, among other things. That means synergy, and maybe a conflict of interest.

I’ll save further analysis of the Philadelphia proposal for future coverage—there’s some logic to a downtown arena near transit, though it poses risks to adjacent Chinatown and comes with some serious spin from its proponents.

But the record in Brooklyn confirms a critical quote in the Inquirer from Vivian Chang, executive director of Asian Americans United: “Studies are about justifying arenas, not analyzing them.”